I’ve seen this ugly movie before and I didn’t like it much that first time, either. I can’t pretend I was touched directly by the violence when Baltimore was last convulsed by riots, but I was close enough—a boy living in the green suburban ring surrounding Baltimore City during the days of violence that followed Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968. I experienced the curfews and the lockdowns and the shuttered schools, the troop trucks on the streets and the olive drab National Guard planes flying low over our house, heading south to the airport where the soldiers would be disgorged and fan out into the city.

I experienced too Barry Oskar (not his real name; I use a pseudonym to spare his surviving family any unnecessary pain), the grandfather of a pair of children who lived on my block. Oskar owned a liquor store in the heart of the violence and announced one evening to family and neighbors that he had shot and killed the first black man to die in the rioting. I didn’t know if it was true or it was a boast — such was Oskar’s naked hatred of African Americans that he would count that a boast. But it had the ring of something he would do, and it wasn’t as if the half dozen killings that occurred in those violent days were going to be aggressively investigated anyway.

The rioting that broke out this week followed the funeral of Freddie Gray, the 25-year-old African American who died at the hands of a dysfunctional white police force that, since 2011 alone, has had to pay out $5.7 million to settle brutality claims. Superficially it felt like a 1968 redux, but the city of now is not the city of then. When I was born, Baltimore was a fault-line place, a town perched on the tipping point between north and south, between the Brown v. Board school desegregation ruling, which had happened not long before, and the voting rights and civil rights acts that were still years away.

The population was openly, racially stratified and businesses that reckoned they could get away with it operated with Jim Crow impunity. When our babysitter, a young African-American woman — as nearly all babysitters were in that time and that place — took my brothers and me to the Uptown Theater to see a revival screening of Pinocchio, the manager scowled at her as soon as we entered, summoned her over and whispered a few cross words.

She came back to us bearing what she gamely framed as the very exciting news that we were all going to get to sit in the balcony. That was fine with me — the balcony was indeed exciting — and it was not until we all got home, my grandmother got word of what had happened and called the theater to rip the bark off the manager that I suspected something more was going on. That something, she made clear to us, had been very wrong.

I didn’t know anything about the primal roots of racism at the time. I hadn’t done any of the reading I’ve done in the decades since about how the brain sorts all people into same and other, tribe and non-tribe, a highly adaptive behavior when we lived in the state of nature but decidedly non-adaptive now. I didn’t know either how powerfully color — of a flag or a uniform or a person — affects that sorting behavior, how easily nonsense like What color is the dress? can morph into What color is the person? And when the answer is black, and the person is young and male, terrible things can happen at the hands of the people who are supposed to be keeping the peace.

I’m glad I didn’t know those things back then, the last time Baltimore burned. Behavioral science can too often be used to make excuses. Laws are fine, but alas, the hearts and minds of men are too often fixed. Best to grow up without that dodge, to learn early on that hearts and minds are as mutable as custom, and that it is every culture’s — and every person’s — responsibility to turn from the dark to the light.

That’s as true of Baltimoreans as of anyone else, but too many people are unsurprised by the current violence. They’ve heard of the city’s stubbornly high murder rate — fifth in the country, behind only Detroit, Newark, New Orleans and St. Louis. Oh, and they’ve seen The Wire — so that pretty much seals things.

But Baltimore’s history and nature run far deeper — the tale of a harbor town, a steel town, a beer-brewing town, an immigrant town. Yes, parts of the city have hollowed out as parts of so many other cities did. And unlike many of those other cities, Baltimore has not enjoyed the same rebound, the same return to the urban core.

But in Baltimore as in the nation as a whole there have been tectonic shifts barely imaginable in 1968. When the lines of authority in a time of civil unrest run from a President named Barack Obama to Attorney General Loretta Lynch to Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake—African Americans all—no one can pretend the world is the same place it was when Lyndon Johnson, Ramsey Clark and Tommy D’Alesandro filled those roles. Rawlings-Blake especially can speak truth to law-breaking power in ways that the white patriarchy never could.

“I’m at a loss for words,” she said angrily as the fires in her hometown flared. “It is idiotic to think that by destroying your city that you’re going to make life better for anybody.”

That idiocy will end. Riots always do when enough rage has been spent. And the question then will be what both the black and white populations of Baltimore, newly chastened, newly shaken, will do. If Rawlings-Blake can shame the looters, someone must also shame the police and their enablers. Otherwise the cycle will never be broken.

Barry Oskar did not live to see Baltimore’s latest burst of violence — indeed, he did not live terribly many years after the murder he liked to brag about. One day he was in his store, behind his counter and an intruder entered with intent to rob. Oskar reached for his well-loved gun but the robber shot fast and first, and the mortal ledger was once again balanced — murder for murder, death for death, the entry made in the blood ink of the race wars. No more, Baltimore. Please stop. You’ve suffered enough.

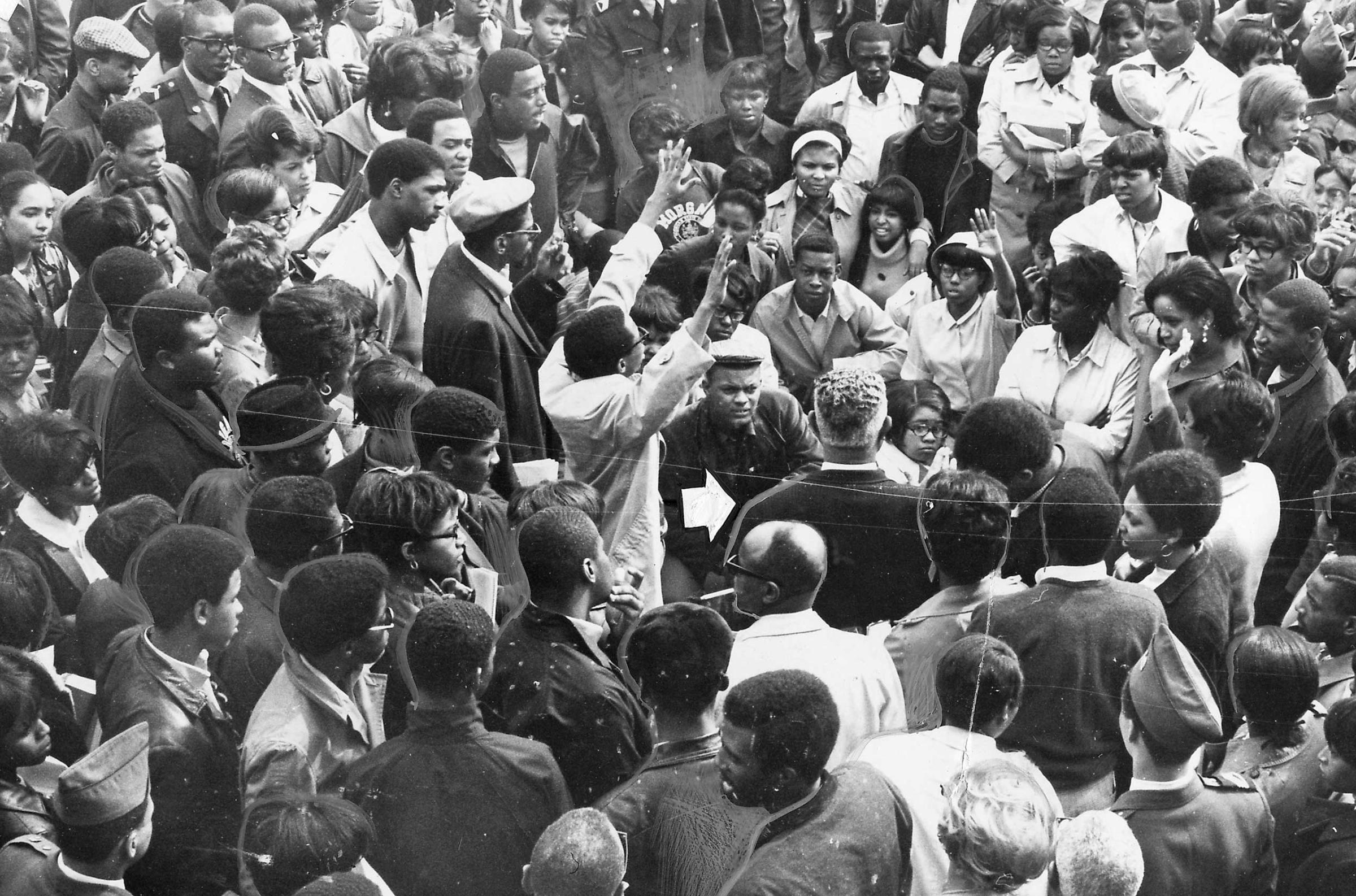

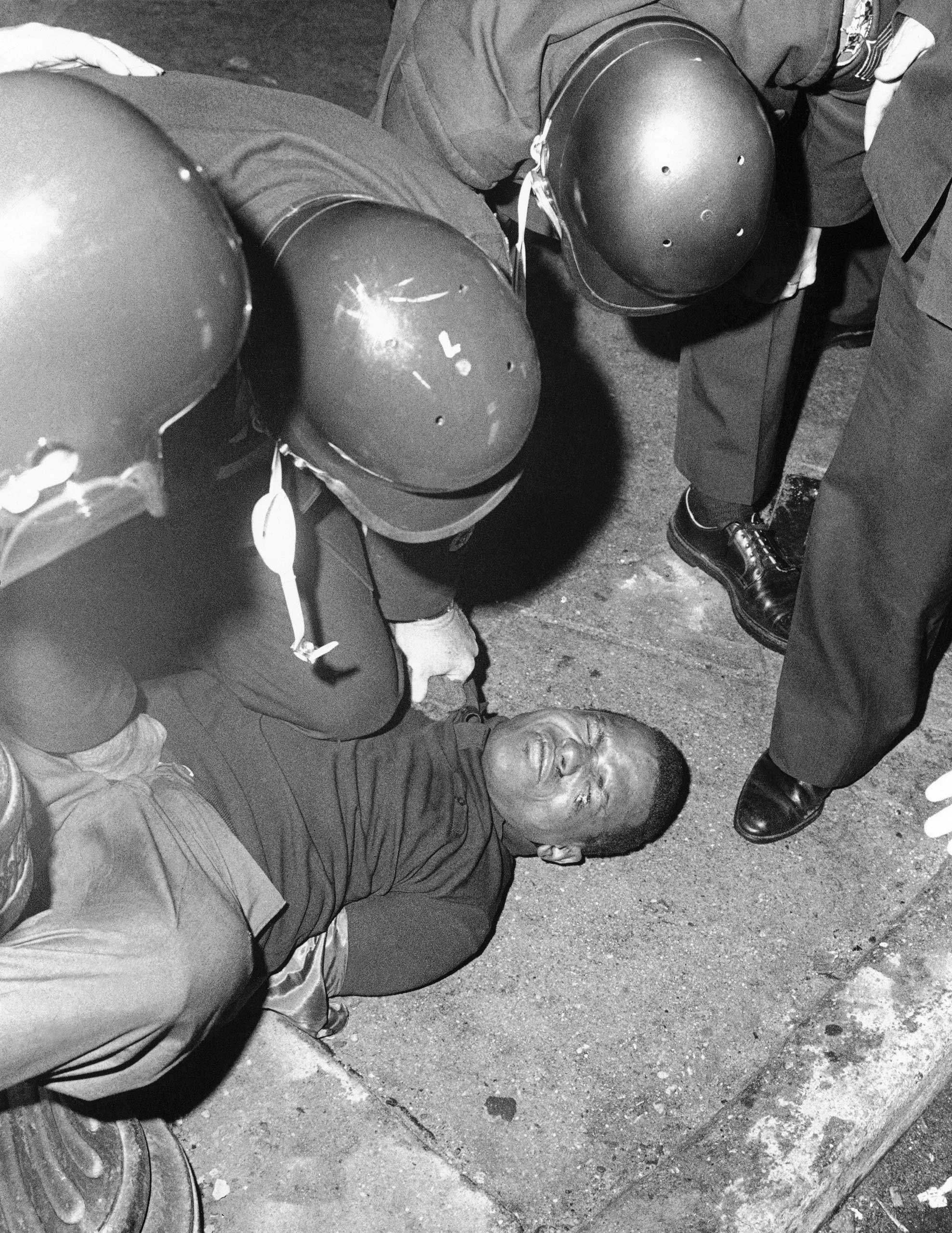

Baltimore Protests, Then and Now

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com