A year in space is marked in part by the holidays that will pass while you’re away. Christmas? Sorry, out of town. Easter? Ditto. Thanksgiving, New Year’s Eve, Halloween? Catch you next year.

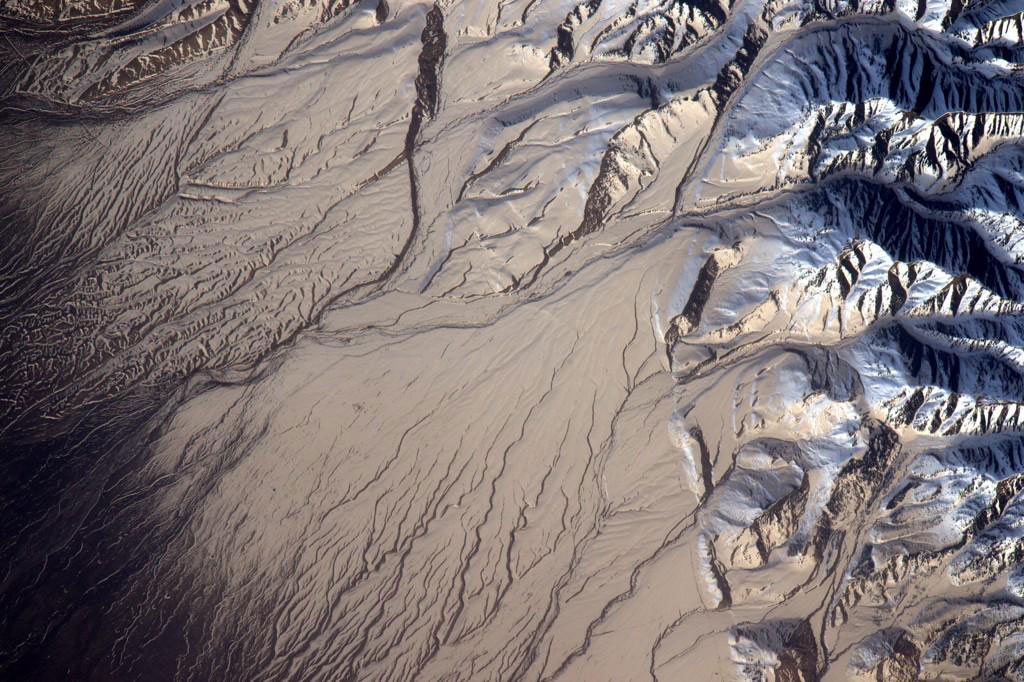

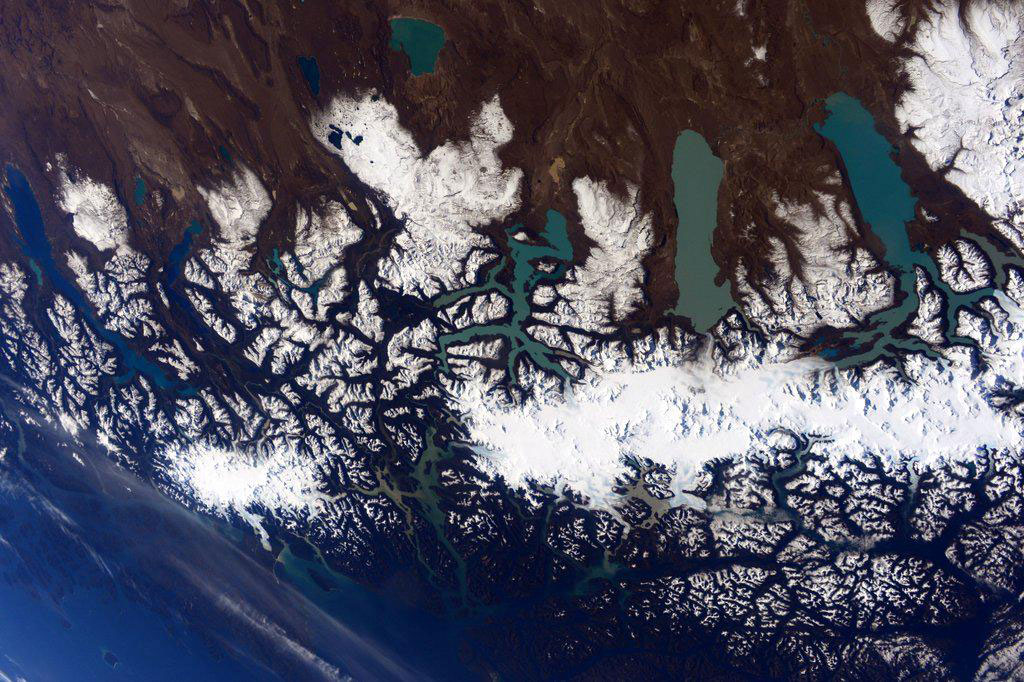

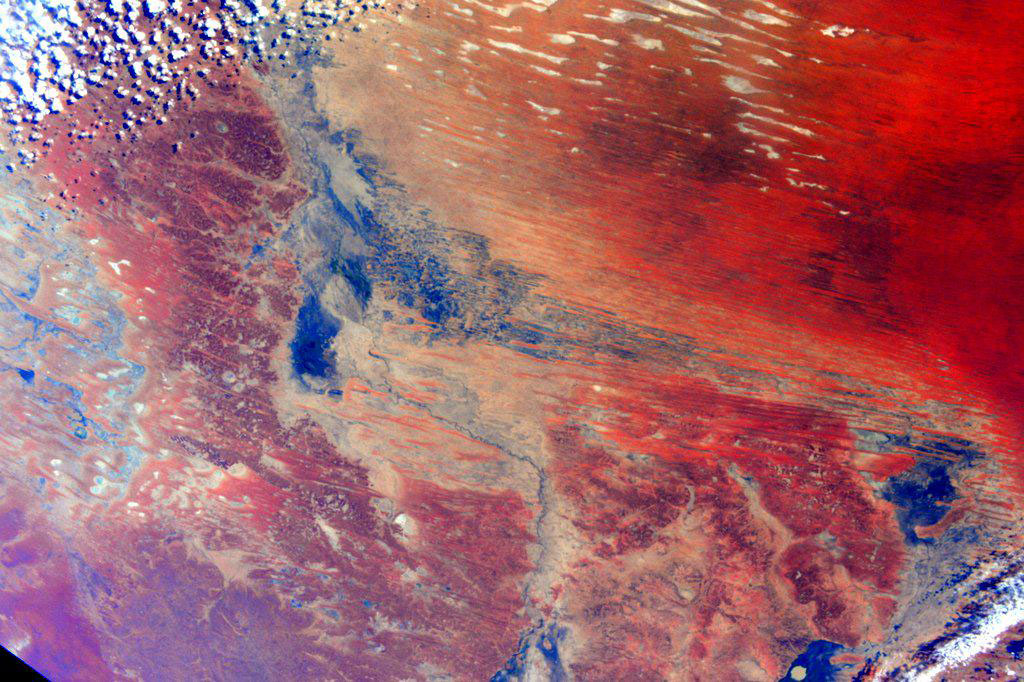

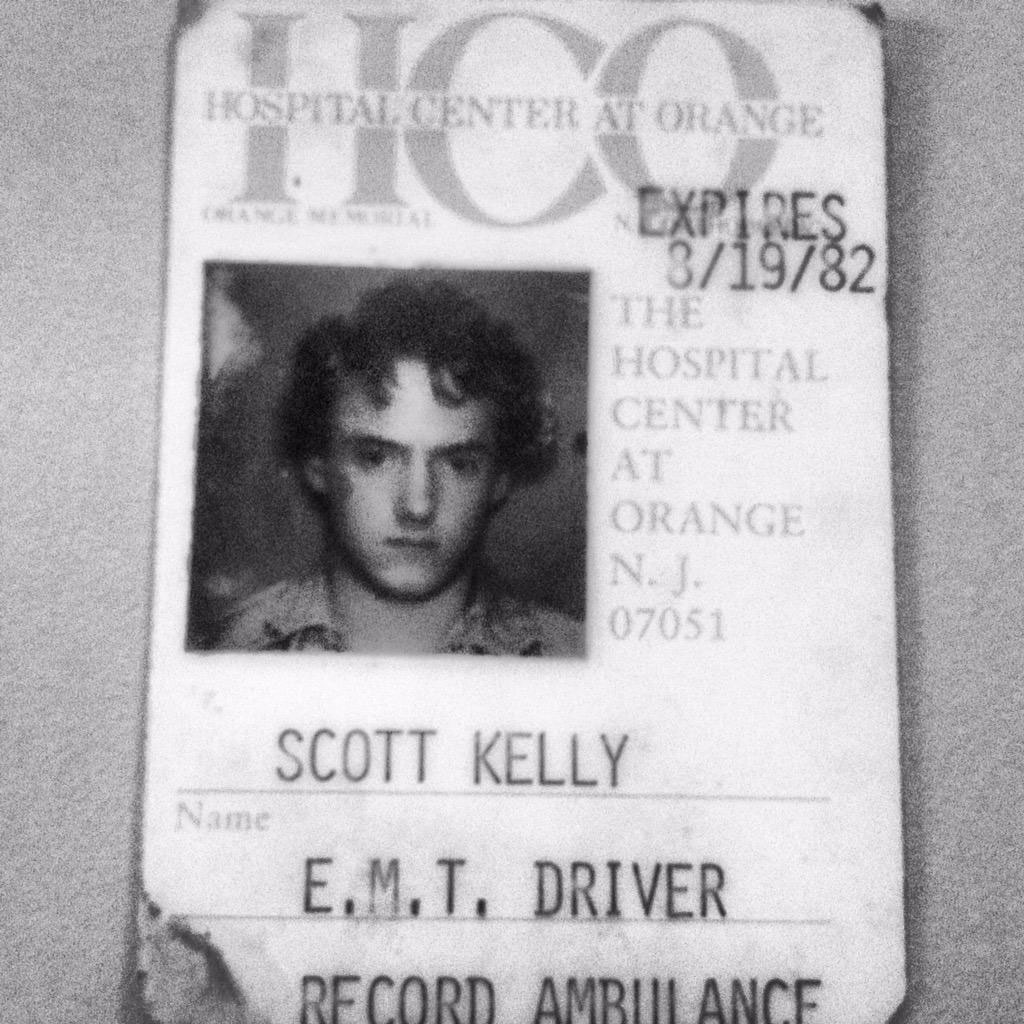

It’s fitting then, that the first holiday astronaut Scott Kelly spent in the just-completed first month of his planned one-year stay aboard the International Space Station (ISS)—which began with his launch from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan in the early morning hours of March 29—was Cosmonautics Day. Never heard of it? You would have if you were Russian.

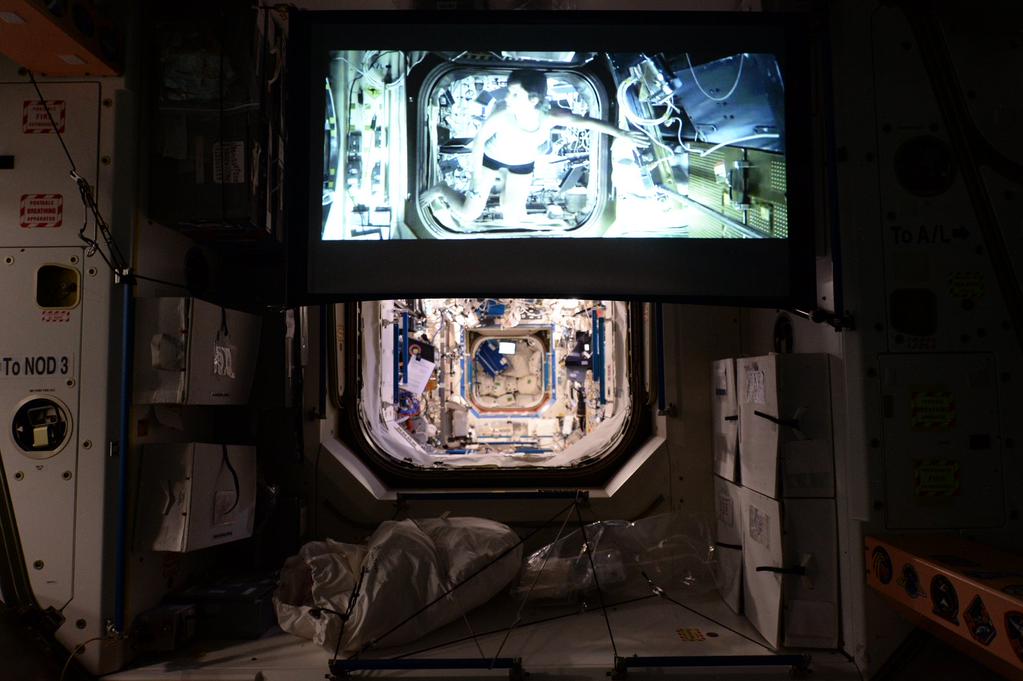

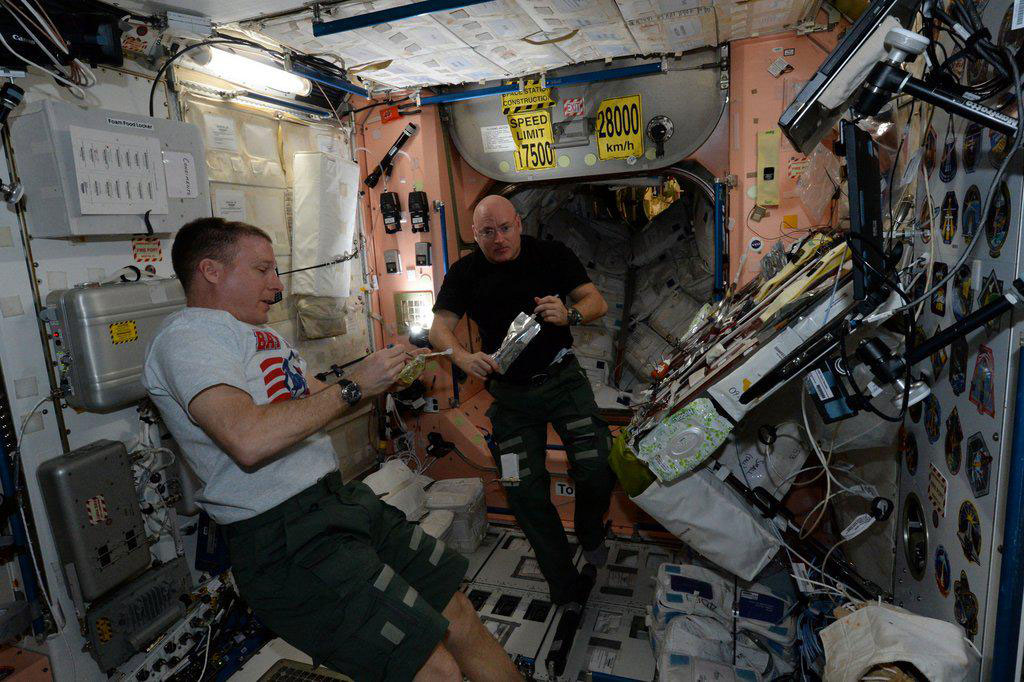

Cosmonautics Day celebrates April 12, 1961, when Yuri Gagarin lifted off from the same launch pad from which Kelly’s mission began, becoming the first human being in space. Kelly and his five crewmates—including fellow one-year marathoner Mikhail Kornienko—got the morning off on this year’s special day, taking the opportunity to enjoy the relative comforts of a spacecraft with more habitable space than a four-bedroom home. But in the afternoon it was back to work—following a moment-by-moment schedule that is scripted on the ground, followed in space and that, while often grueling, is the best way for astronauts and cosmonauts who have signed on for a long hitch to keep their minds on their work and keep the time from crawling.

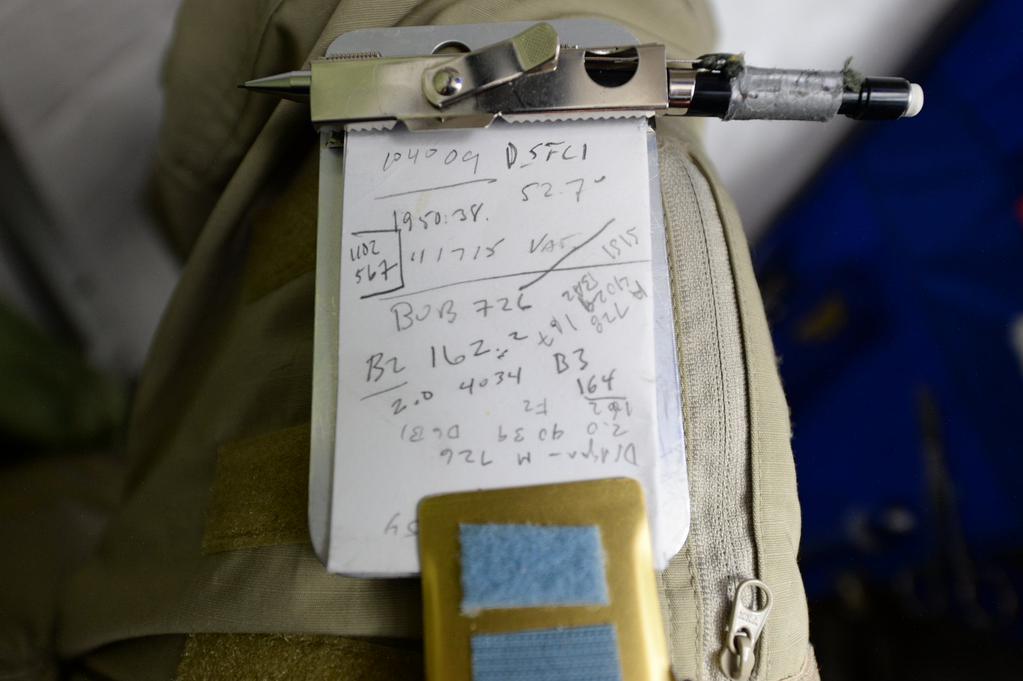

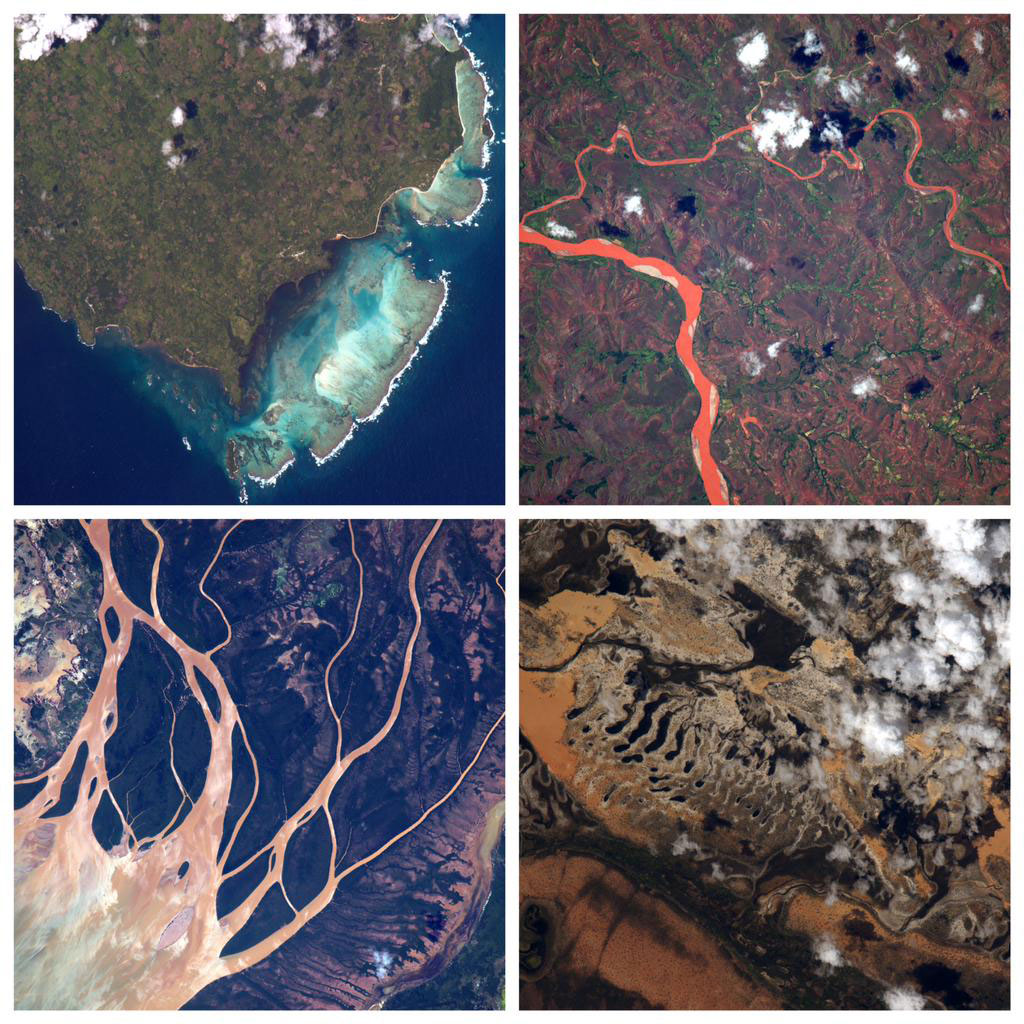

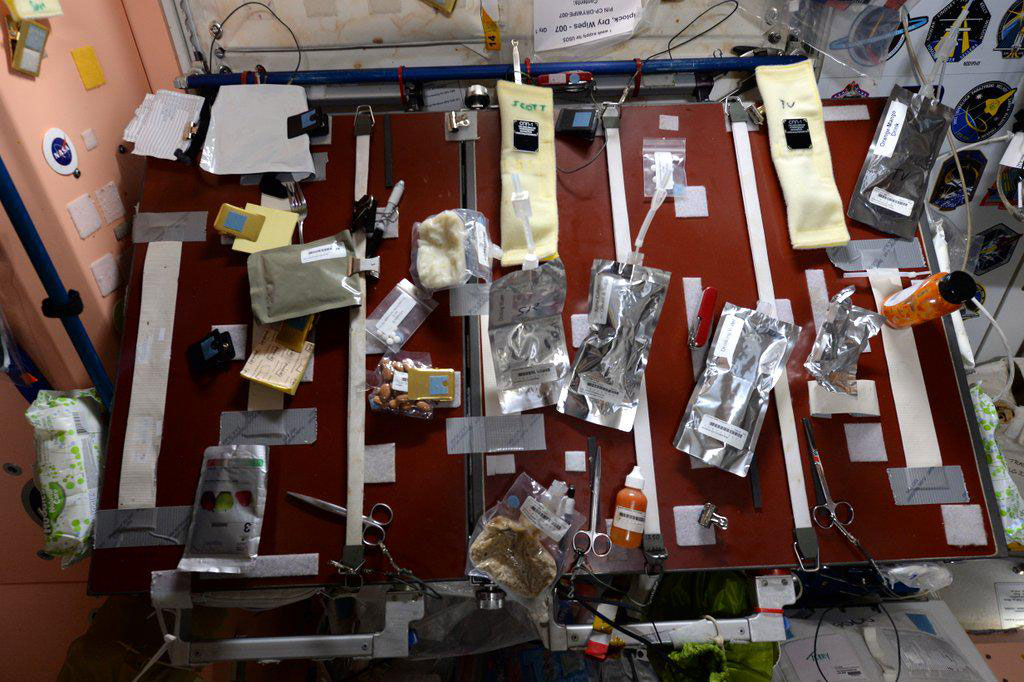

Kelly’s first month was, in some ways, typical of the 11 that lie ahead. There was the arrival of a SpaceX cargo ship—a vessel carrying 4,300 lbs (1,950 kg) of equipment and supplies, including a subzero freezer that can preserve experiments at -112º F (-80º C)—that needed to be unloaded; new gear to aid studies of the effects of microgravity on mice; and a sample of so-called synthetic muscle, a strong but pliant material modeled after human muscle, to be used for robotic limbs and joints. Also tucked into the load was a less practical but infinitely more anticipated item—a zero-gravity espresso machine, dubbed the ISSpresso.

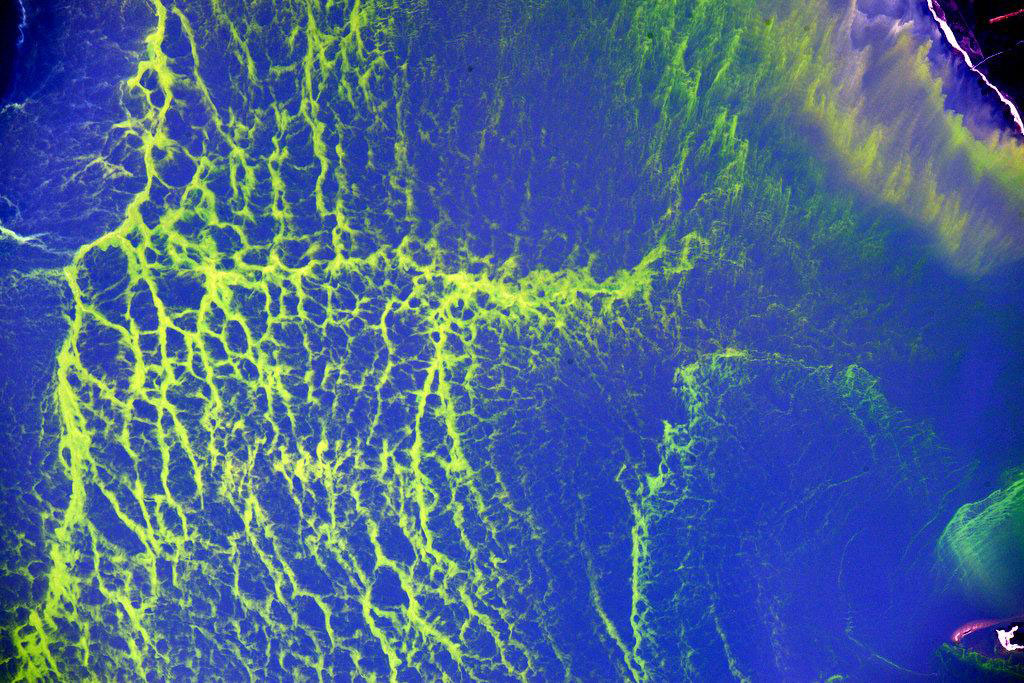

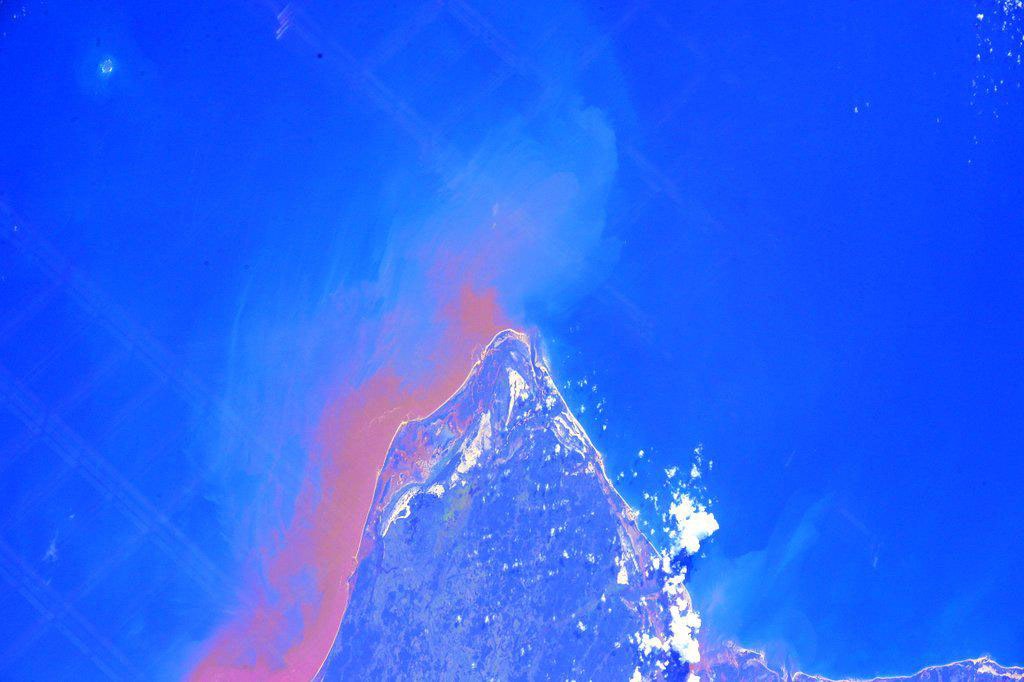

See Scott Kelly's First 30 Days in Space

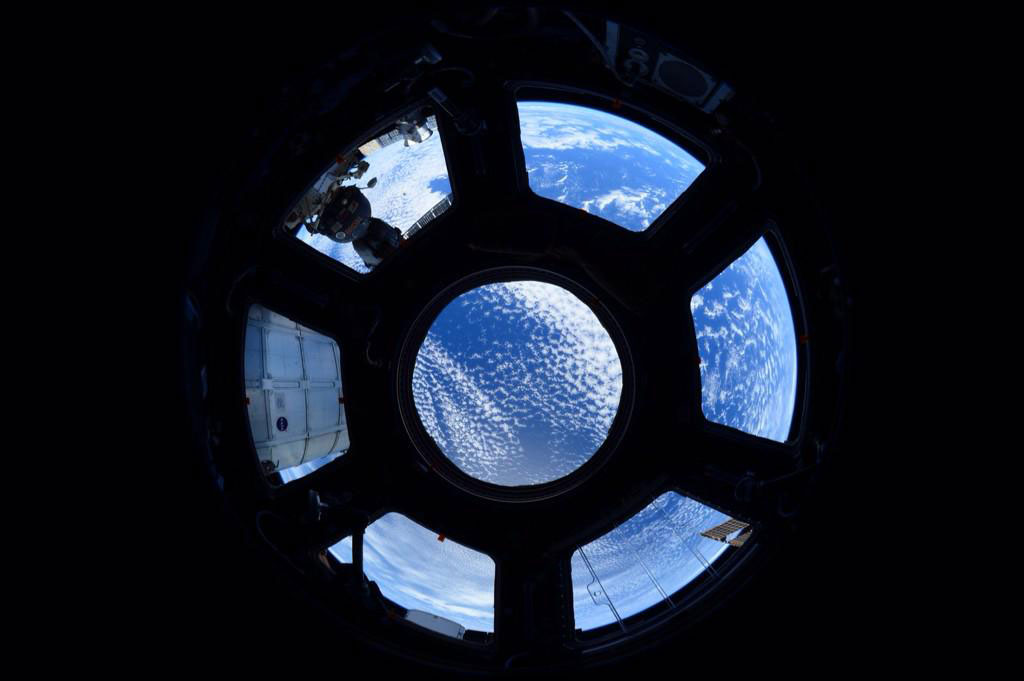

There are 250 experiments that must be tended at any one time aboard the ISS, but the most important of them will be Kelly and Kornienko themselves. The human body was built for the one-g environment of Earth, but if we ever hope to achieve our grand dreams of traveling to Mars and beyond, we’d better figure out if we can survive the rigors of zero-g. And that’s no sure thing. Almost every system in the body—circulatory, skeletal, cellular, visual—breaks down in some ways in weightlessness.

In their first month in space alone, the two long-termers submitted to a whole range of preliminary experiments that will track their health throughout their stay: their eyes are being studied to determine the kind of effect the upward shift in fluids caused by zero-g has on the optic nerve and the shape of the eyeball. Space physicians already know the basic answer: not a good one. But the hope is that Kelly and Kornienko will help provide ways to mitigate the damage.

Other biomedical studies in the first month include sampling saliva and sweat to test for bacterial levels and chemical balance; leg scans to determine blood flow; studies of blood pressure—which can fluctuate wildly when the heart no longer has to pump against gravity; analyses of throat and skin samples; bone density tests and studies of the cells to determine why they change shape in zero-g. As exquisite serendipity has it, Kelly’s identical twin brother, Mark, is a retired astronaut, providing a perfect controlled study of how men with matching genomes and matching backgrounds react to a year spent in decidedly non-matching environments. Nearly all of the studies Scott submits to in space will be duplicated in Mark on the ground.

The eleven months ahead will not all be a Groundhog Day repetition of the first. Kelly will venture out on at least two spacewalks—the first of his four-mission career—and will help oversee a complex reconfiguration of the station, with modules and docking ports repositioned to accommodate commercial crew vehicles built by Boeing and SpaceX, which are supposed to begin arriving in 2017. There will also be movie nights and web-surfing and regular video chats, phone calls and emails with family. And the periodic arrival of cargo ships will provide such luxuries as fresh fruits and vegetables, which don’t last long in space, but don’t have to because six-person crews missing the comforts of home scarf them down fast.

The clubhouse turn of Kelly’s and Kornienko’s one-year mission will occur next December, the 50th anniversary of what was once America’s longest stay in space: the two-week flight of Gemini 7, which astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Lovell passed in the equivalent of two coach airline seats, with the ceiling just three inches over their heads. The ISS is a manor house compared to the Gemini. But the astronauts are still astronauts, human beings in a very strange place experiencing very strange things—in this case for a very long time.

TIME is covering Kelly’s mission in the new series, A Year In Space. Watch the trailer here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com