Some 750 asylum seekers living in Australian government detention on the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru face an impossible choice. They can stay on Nauru in squalid conditions. Or they can be resettled, of all places, in impoverished Cambodia — a country with a long record of human-rights abuses, where refugees are discriminated against and the chances of finding work are slim.

At first glance, it would appear that anybody would give anything to leave Nauru. About 200 refugees whose asylum claims have been processed live in small clusters of houses dotted around the island. But those awaiting a decision on their claims are kept in two detention centers, one for single men and another that houses families. There, people who’ve fled war and persecution in countries like Syria, Somalia, Burma, Sri Lanka and Iran sleep in sweltering and cramped plastic tents with little ventilation. They have limited communication with the outside world and many spend their days in fear and despair.

Pamela Curr, a refugee-rights advocate for over a decade, is the campaign coordinator for the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, a Melbourne-based organization that provides health, food, aid, legal and counseling programs to asylum seekers in Australia. Curr was told by a female inmate in Nauru of an 8-year-old boy living in the detention center, who had become withdrawn and refused to leave his mother’s side, even to go to school. When his mother asked him to “draw something for me, anything you like,” he burst into tears and drew a Nauruan guard with an erect penis.

Women are also reportedly preyed upon in the camp, too afraid to even visit the toilets. “We wet ourselves because the guards stand around the toilets at night and we’re terrified we’ll get raped,” one woman told Curr.

To add to their distress, just last week the Nauran government blocked access to Facebook on the island, in what it said was an attempt to crack down on Internet pornography. Now, the refugees and asylum seekers who used the social-media site as a lifeline to contact loved ones must rely on expensive and unreliable pay phones.

Resettlement in Australia is not an option for any of the inmates on Nauru. Canberra has repeatedly vowed that no asylum seeker attempting to reach its shores by sea will settle there.

“You will not under any circumstances be settling in Australia. This is not an option that the Australian government will ever present to you,” Australia’s Minister for Immigration and Border Affairs Peter Dutton said in a video address, obtained by the Guardian two weeks ago.

With all of that being the case, the Australian government probably thought, when it made a resettlement pact with Cambodia last September, that the detainees on Nauru would jump at the chance of an onward journey. Under the deal, Cambodia would resettle an unlimited number of asylum seekers from Nauru in exchange for $31 million and the assurance that Australia would fund the resettlement process for at least one year.

Those who sign up to go are promised long-term support in the areas of work, education and health care. But immigration officials are struggling to find volunteers among the island’s refugees to be on the first Cambodia-bound plane, which could depart this week.

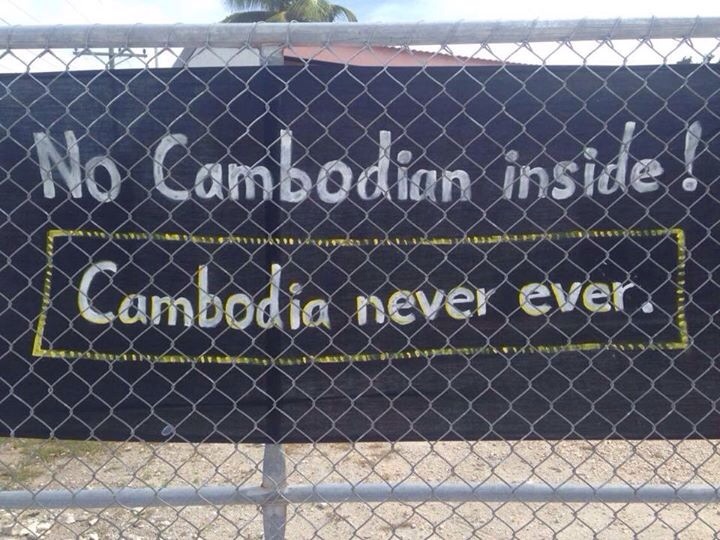

Last Friday, about 200 refugees demonstrated in the eastern Ijuw camp on Nauru against relocation to Cambodia. They held up banners with slogans calling for justice and chanted “Cambodia, never ever.”

Australian officials are reportedly offering incentives of nearly $12,000 to any asylum seeker that will step aboard, and are offering to fast-track asylum claims for refugees who agree to go, according to Ian Rintoul, coordinator for a Sydney-based refugee-campaign group, Refugee Action Coalition.

“An Iranian couple, the latest to agree to be transferred, have almost certainly had their refugee determination fast-tracked. They were determined to be refugees only five days ago,” he said in a statement last Wednesday.

Refugees have been warned that if they are not among the first to be resettled, they may not be guaranteed the same financial help if they decide to go at a later date, a caution repeated by Dutton in his video address.

“Our concern is without advice, people may be lured into accepting the offer because it may seem to them the only way to get a refugee visa is to accept the money,” Rintoul tells TIME.

In the video, reportedly shown to Nauru asylum seekers two weeks ago, Dutton implored those in detention to take up the resettlement offer, saying: “Cambodia provides a wealth of opportunity for new settlers, it is a fast-paced and vibrant country with a stable economy and varied employment opportunities.”

However, international and local advocacy groups, as well as opposition lawmakers in Australia and Cambodia, have slammed the resettlement plan as a violation of refugee rights and condemn the government for sending vulnerable people to a country that struggles to take care of its own citizens.

“While the Australian government tries to market the Cambodia deal as being about constructive burden-sharing, it’s really about destructive burden-shifting,” Daniel Webb, director of legal advocacy for the Human Rights Law Centre in Melbourne, tells TIME.

Phil Robertson, deputy director for Human Rights Watch in Asia, says, “Far from a tropical democratic paradise, the reality is that Cambodia is a struggling economy with ineffective law enforcement where its own citizens face corruption, repression and violence on a regular basis.”

In what appear to be fact sheets, reportedly distributed by Australian officials among some of the asylum seekers on Nauru last month, the Australian government states that Khmer citizens enjoy the “freedoms of a democratic society including freedom of religion and freedom of speech.” Canberra also promises that refugees will start a new life “free from persecution and violence” and says Cambodia offers “jobs for migrants and strong support networks for newly settled refugees.”

But in reality, Cambodia is extremely poor, with 17% of its population living in poverty and thousands of its citizens forced to seek work in neighboring Thailand as migrant laborers. Though the country has undergone rapid development in the past decade, services like health care are woefully lacking and not up to international standards.

Cambodia also has a grim record of human-rights abuses of its own citizens and the government has been known to stifle peaceful protests and detain opposition activists. In November 2014, 10 women were jailed merely for protesting against flooding in their community.

The existing 75 registered refugees already living in Cambodia have also struggled to find work. They face extortion and discrimination and “live below the poverty line, below the fringes of society,” says Graeme McGregor, refugee-campaign coordinator for Amnesty International in Australia.

Among the refugees in Cambodia are people from nearby Burma, Sri Lanka and neighboring Vietnam. According to Human Rights Watch, though they have refugee documentation enabling them to stay in the country, their papers are not recognized by many employers and they face legal barriers when opening bank accounts.

Without a grasp of the Khmer language, the refugees have struggled to enter the job market and many live hand-to-mouth, relying on organizations like the U.N. refugee agency (UNHCR) and other nonprofits for school supplies, tuition fees and health insurance.

“This is a corrupt country. You will not find jobs. We have been here more than two years and we have no money and not enough to eat. It’s better to wait in Nauru,” one refugee told Human Rights Watch.

Cambodia also has a track record of sending refugees back to the places from which they have fled. In 2009, 20 Uighur asylum seekers were deported to China, where they were arrested and jailed. And in the past four months, Cambodia has forcibly deported 54 ethnic Jarai and E De people (also known as Montaganards) back to Vietnam.

Incredulously, Australia’s own guidance to its citizens on Cambodia, published by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, contradicts much of what the government is saying to refugees on Nauru.

Despite this, the government blames “troublemakers within the asylum-seeker community” on Nauru for turning others against going. That’s according to an interview conducted by Dutton with the U.K.’s Sky News on April 26.

When asked by TIME to comment on the issues raised in this article, the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection issued a generic statement saying: “The Australian Government remains committed to that agreement [with Cambodia] and the first group of volunteers is anticipated to depart for Cambodia in the near future.”

At Cambodia’s request, the International Organization of Migration (IOM) will help with the resettlement process alongside other aid agencies in the country, providing the refugees with temporary accommodation and long-term help with finding work and learning the language. The IOM agreed to assist after Phnom Penh promised to grant all existing and arriving refugees the right to live and work anywhere in the country, the right to family reunions, long-term funding for the program and fair treatment for all refugees.

While the conditions offer some assurance that life for refugees may improve in Cambodia, it is understandable that those people on Nauru, who have fled persecution and war, and who have endured smuggling and perilous boat journeys, are fearful of being dropped in an unknown country to start anew, especially when they sense they are not being given the full picture about what awaits them.

“Australia is once again violating obligations under international law as the refugee convention requires asylum seekers to be processed and resettled in Australia,” says McGregor, adding, “Their safety isn’t guaranteed right now in Cambodia.”

So far, just four people from Nauru have signed up to the offer, including an Iranian couple, an ethnic Rohingya man from Burma, and another Iranian man. Australia hopes that once they settle into their new life in Cambodia, they will encourage others to join them. But right now, Cambodia is looking even less attractive than a crushingly monotonous life in a bunch of flyblown tents somewhere in the Pacific.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Helen Regan at helen.regan@timeasia.com