Late last year, as the trial of the Boston Marathon bomber was nearing its conclusion, an old friend of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s family realized it was time for him to leave his home in Massachusetts and go back to his native Chechnya.

Khassan Baiev, a renowned physician, had spent more than a decade by that point doing charity work around Boston, mostly aimed at bringing American medical care to children in Chechnya and other parts of southern Russia. But after the marathon bombings in 2013, and the subsequent trial of the younger Tsarnaev brother, it was nearly impossible to continue this type of philanthropy.

“People began telling me that they can’t help Chechnya after what happened, or they won’t,” says Baiev. “So I didn’t see a choice. I had to accept that the bonds I had built were broken.”

The strain on Baiev’s ties with American donors began to show soon after the blasts, when police identified the suspects as Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, whose father hails from Chechnya. Although the brothers had never actually lived there, the region’s reputation among the American public was so badly stained after the bombings that even raising small donations for its children became a struggle, Baiev says. “It was like the entire nation became associated with terrorism.”

That shift in the American consciousness, he says, has hurt many ethnic Chechens who had nothing to do with the bombings. According to the prosecution, the Tsarnaev brothers, both adherents of a radical strain of Islam, had intended to punish the U.S. for its wars in the Muslim world. The two bombs they detonated near the race’s finish line wounded hundreds of innocent people and killed three others on April 15, 2013, including an 8-year-old boy. Days later, Tamerlan was killed in a shootout with U.S. law enforcement, while his younger brother was arrested, put on trial and finally convicted this month. On April 21, the jury in Boston will consider whether to sentence Dzhokhar Tsarnaev to life in prison or the death penalty.

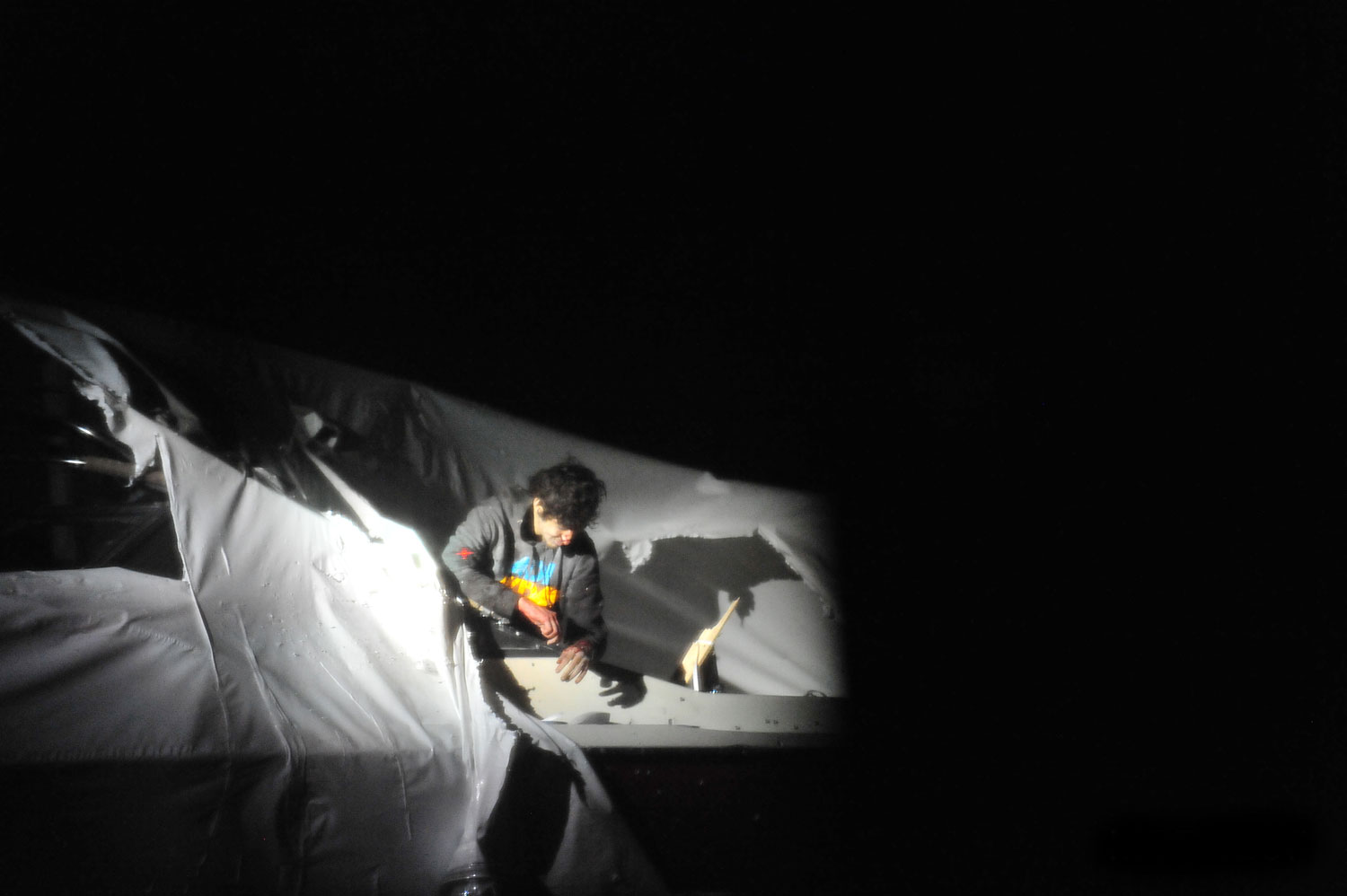

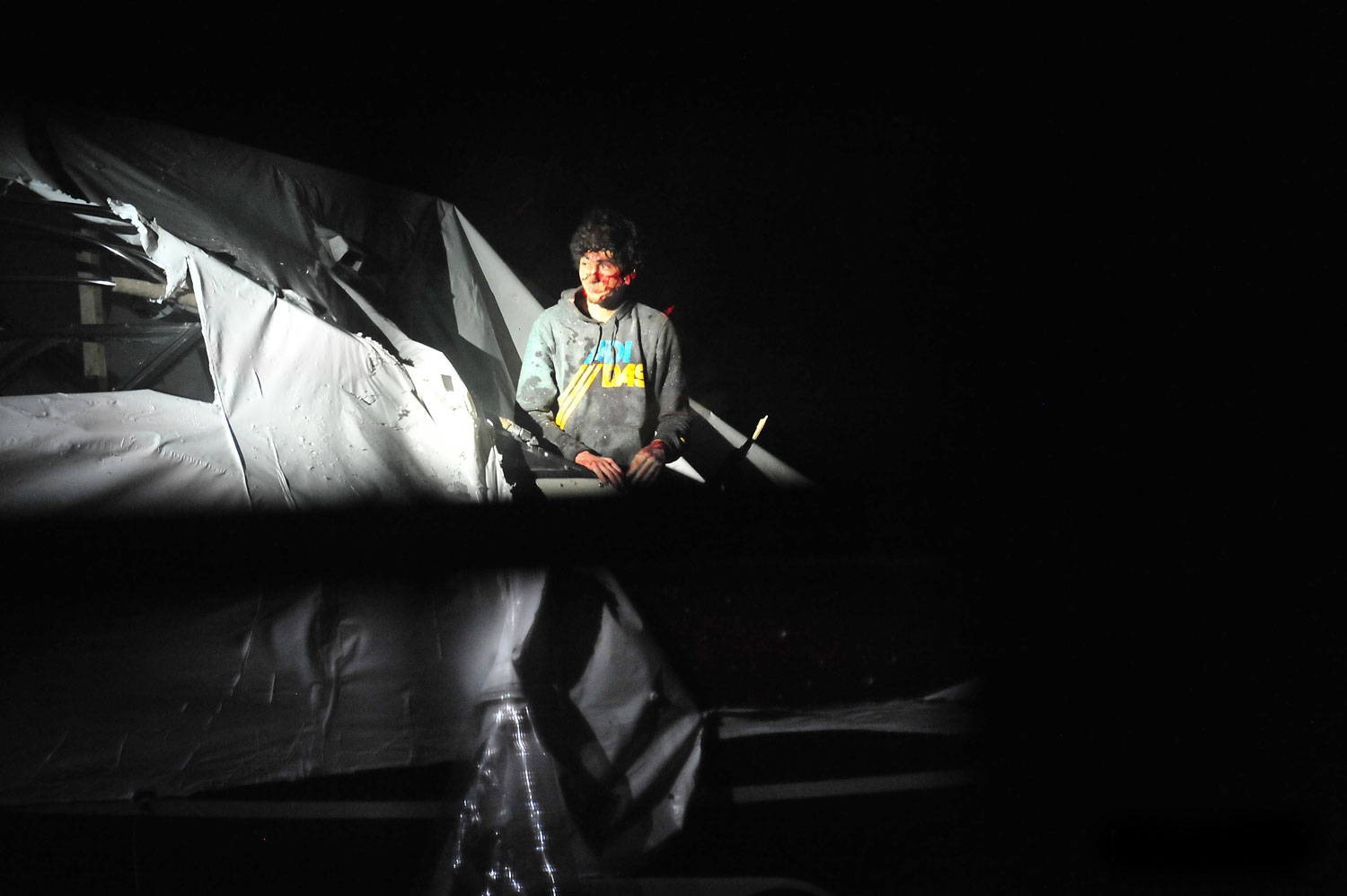

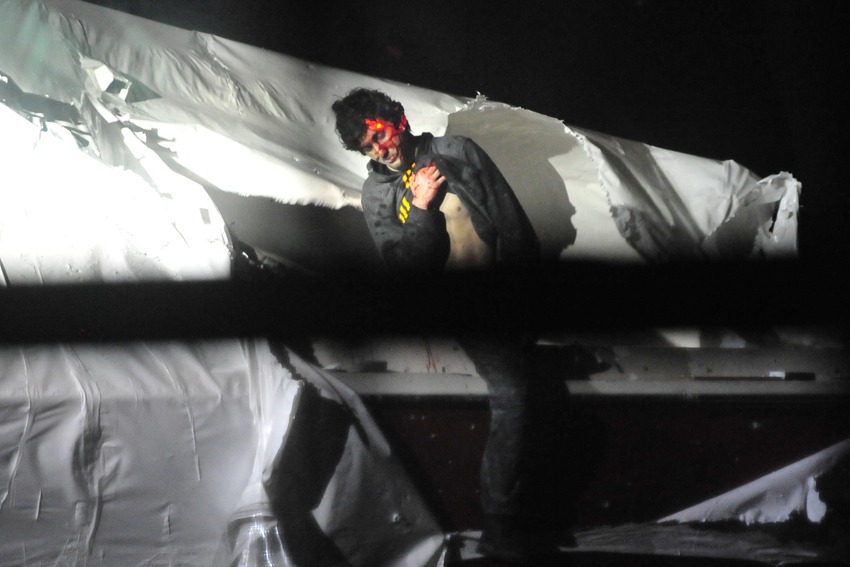

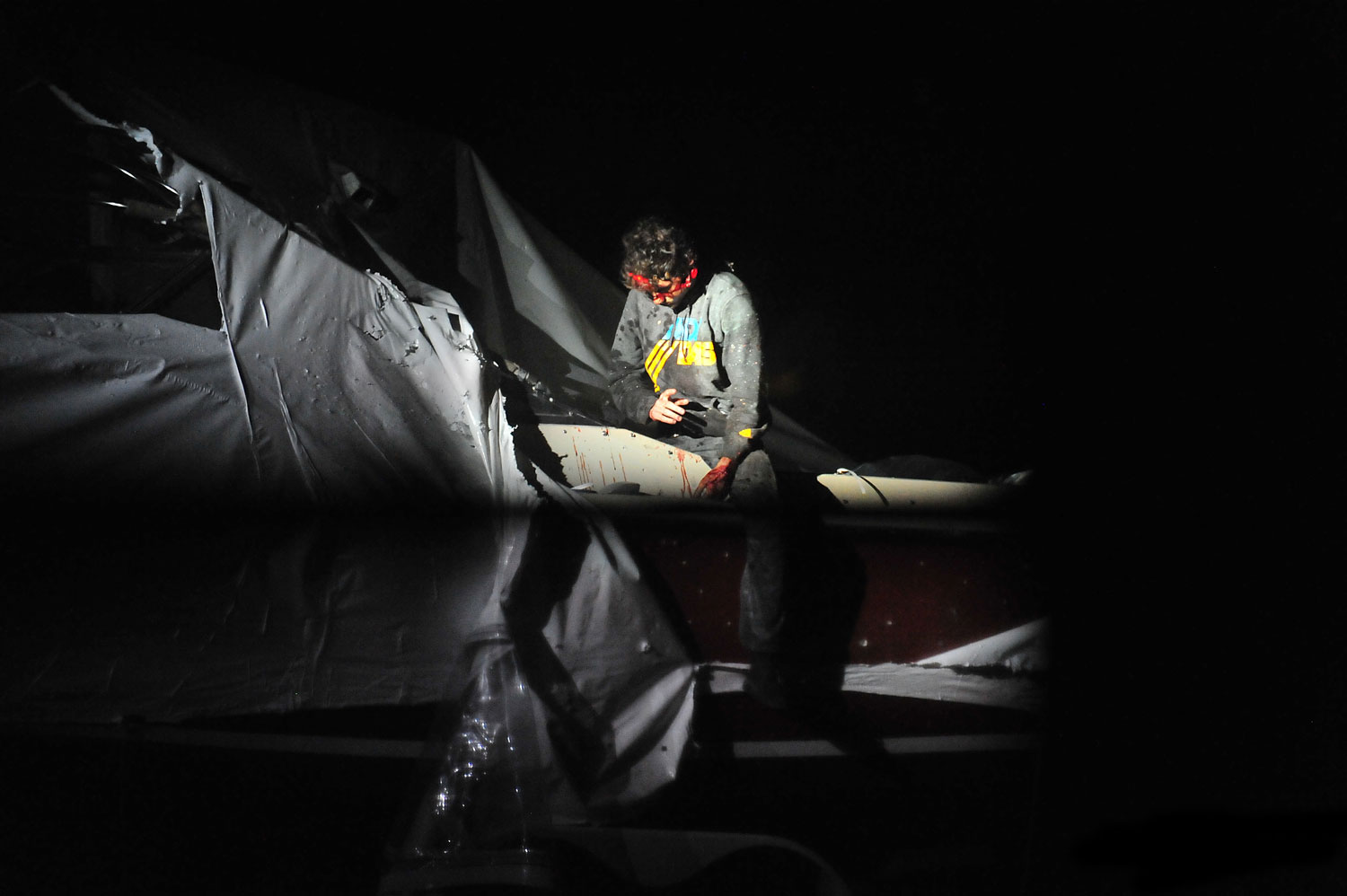

Photos: The Last Moments of the Man Hunt for Boston Bombing Suspect

The 21-year-old has so far expressed no public remorse over the bombings. But whatever suffering he intended to cause Americans, Tsarnaev could hardly have planned to do so much harm to the people of Chechnya, whom he had claimed to love and identified with while growing up in the Boston area. “Most doors are closed to us after what happened,” says Heda Saratova, a leading rights campaigner in Chechnya who has helped many families in the region seek asylum in the West. Since the marathon bombings, she says, it has become far more difficult, and usually impossible, for even the most persecuted and vulnerable people in Chechnya to be granted U.S. asylum.

Few are more vulnerable than the thousands of children born with birth defects in Chechnya, often as a result of the region’s wars with Russia in the 1990s, and many of them have found themselves cut off from the medical care that Baiev’s charity was previously able to provide.

For more than a decade, Baiev had served as a vital link between his homeland and the U.S. medical establishment, which has long held him up as a model of courage and selflessness. While most Chechen doctors fled the region during its wars against Russia, Baiev stayed behind to work as a battlefield trauma surgeon, treating wounded combatants from both sides of the conflict even as his operating room quaked with the thuds of Russian artillery. He often lacked basic supplies, even rubber gloves, but after one particularly ferocious battle, he conducted at least 67 amputations and eight skull surgeries in the course of two days, pausing only once to drink a cup of coffee.

Throughout the wars, his willingness to treat the wounds of Chechen rebel leaders made him a target for the Russian forces, who repeatedly detained him and, he says, subjected him to frequent beatings. He earned no less scorn from many of his fellow Chechens for performing surgeries on wounded Russian soldiers. But his dedication to the Hippocratic oath, which obliges a physician to treat the injured regardless of their politics, made him a hero of the medical profession, and he was granted political asylum in the U.S. in 2000.

Two years later, in the spring of 2002, the 8-year-old Dzhokhar Tsarnaev arrived with his parents at Baiev’s doorstep in Needham, Mass. They were part of the wave of Chechen refugees then seeking asylum in the U.S., and a relative in Canada had given them Baiev’s phone number, suggesting he may be able to help. “I’d never seen or heard of them before they called me that day,” he says. For about a month, he let the Tsarnaevs live with him while they were looking for a place of their own. (Tamerlan Tsarnaev and his two sisters joined the family later that year.)

From the weeks they spent living together, Baiev remembers the young Dzhokhar as a “quiet but willful” boy who found easy friends in the neighborhood. “He was a totally normal kid, loved to play, loved life.” After they found their own apartment in a Boston suburb, the Tsarnaevs never stayed in touch with Baiev, and the doctor was in any case too busy lecturing and campaigning to keep up with all his Chechen friends in the area.

The book he published in 2003 describing his experience during the wars — The Oath: A Surgeon Under Fire — went on to become standard reading for American medical students, and later that year, he became the director of a charity called the International Committee for the Children of Chechnya (ICCC), which soon began organizing trips for American surgeons to visit the region to treat children affected by the wars.

There was never any shortage of patients, he says, because “Chechnya was like a testing ground for Russian weapons. God only knows what they dropped on us.” Although the Russian government has never conducted a public study on the rate of birth defects in Chechnya since 2000, Baiev contends that it is many times higher than the global average, leading in particular to cleft palates and other physical abnormalities.

In the decade before the Boston Marathon bombings, he and his U.S. colleagues provided free treatment to thousands of children born in Chechnya with such conditions, usually during the visits to the region that Baiev would organize once a year. For his service, the health-advocacy group Physicians for Human Rights honored him at a gala in Boston in 2006, and he showed up to receive the award with his typical flair, wearing the traditional garb of a Chechen warrior. (To pass security at the event, his friends convinced him to leave the outfit’s ceremonial dagger in the car.)

But the visit to Chechnya he organized for U.S. doctors in the fall of 2014 turned out to be his last with the ICCC. “We just couldn’t find enough support in America after what the Tsarnaevs did,” he says. As a result, he decided at the end of last year to close the charity down. Now, even though most of his family still lives in the U.S., Baiev has moved back to Grozny to work full-time at the local children’s hospital. “I felt there was more I could do here on my own,” he tells TIME during a recent visit to his ward, which he now runs with two local doctors.

Each morning, he puts on the scrubs he got from Harvard Children’s Hospital and makes the rounds of the cramped but spotless facility in Grozny. The desk in his office is decorated with a little American flag and a miniature version of the Statue of Liberty, both symbols of the years he spent building bonds between the U.S. and Chechnya. “But it feels like a lot of that effort was wasted,” he says.

After the marathon bombings, he feels it could take years for his region to regain the sympathy of the Americans who once aided his work so generously. And though he doesn’t seem to blame anyone for withdrawing that support, he says he can’t help but see it as another link in a chain of injustice.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com