Ethan Czahor’s dreams collapsed on the national stage earlier this year. The 31-year-old age digital whiz had spent years positioning himself to work in politics and earlier this year Jeb Bush’s campaign came calling, hiring Czahor as its chief technology officer.

He lasted 36 hours, done in by a history of offensive tweets and blog posts that was uncovered by reporters and opposition researchers after TIME broke the news of his hire.

Now, two months later, he is looking to make his comeback, turning lemons into lemonade with Clear, an app designed to keep what happened to him from happening to anyone else.

“Why wasn’t I smart enough to take care of this before it happens,” Czahor asked himself for weeks after the controversy, he told TIME. Now he’s set about making sure people can manage potentially damaging social media histories.

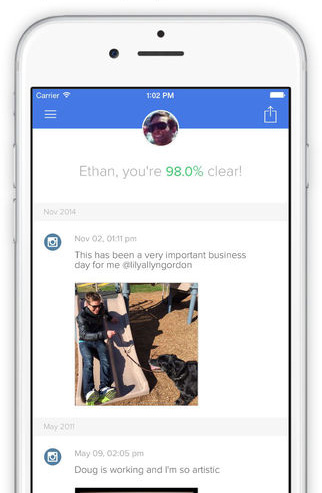

The app, releasing publicly Monday, scours a user’s Twitter, Facebook and Instagram histories for potentially inflammatory or damaging posts, and makes their removal a breeze. It’s designed for the next generation in the workforce, who grew up sharing vast amounts of information online, some of which may become a liability in their future careers.

“This could happen to anyone in any field—it doesn’t have to be politics—every millennial is now entering the workforce, and maybe even a senior position, and everything that they’ve said online for the last 10 years is still there, and that’s a new thing for this generation,” Czahor said.

Already, there’s a long history of political aides being done in by their social media postings. Last month, GOP operative Liz Mair was forced to resign from a top digital post for Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker after old tweets surfaced showing her criticizing the first-in-the-nation caucus state of Iowa. Benjamin Cole, a senior aide to disgraced Rep. Aaron Schock was forced to resign after racist Facebook posts were dug up. In 2008, former Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau was forced to apologize after a photo emerged of him groping a life-sized cut-out of then-Sen. Hillary Clinton.

The app works by flagging postings that contain watchwords: the obvious four letter ones, as well as “gay,” “Americans” and “black.” Posts are also subjected to sentiment analysis, using IBM’s Watson supercomputer, to try to flag additional negative messages. The app’s algorithms are far from perfect, but it errs on the side of caution. The Clear analysis of this reporter’s Twitter, Facebook and Instagram accounts scored a -2,404—a record low in the private beta—from the app’s proprietary grading system which calculates the potential liability of a person’s social media history.

It will soon be converted to a traditional 0-100 scale, Czahor said, with higher scores meaning safer profiles. (One reason for this reporter’s low rating: quotes from presidential candidates frequently scored as negative, while words on the watch list triggered alerts.)

“The most challenging part of this is determining which tweets are actually offensive, and that’s something that will take a while to get really good at,” Czahor said.

Czahor, who moved to California after college to test his hand at improv comedy at The Groundlings while working at Internet start ups, maintained that the offending comments that cost him the Bush job were meant to be good-natured. “I was telling jokes with my friends and they were completely tongue-in-cheek and completely harmless,” he said. “But years later after I had forgotten about them, they’d been pulled out of context and it looked terrible.”

“Most people don’t know that halloween is German for ‘night that girls with low self-esteem dress like sluts,'” one, now-deleted tweet read. “When I burp in the gym I feel like it’s my way of saying, ‘sorry guys, but I’m not gay,'” said another.

Clear is purely a defensive weapon, and can’t be used the growing class of opposition researchers against whom Czahor is looking to protect. The app requires that users grant access to their social media accounts, meaning, that a third party can’t review a user’s history without their consent.

Czahor said he believes that racist and other offensive postings should be held to account, saying Clear was designed for the universe of embarrassing messages that can simply be taken out of context months or years later.

While some messages, if public, may be captured in public archives and thus out of the reach of the app’s delete feature, Czahor said he believes the awareness alone of what a person tweeted or posted years ago is a valuable resource. “When this was happening,” Czahor added, “there were all of these emails asking how I felt about this statement or that statement, and I remember thinking ‘did I even write this?’”

Czahor said the next step would be to expand the app’s reach to emails, personal blogs, and search results, pointing to the embarrassing leaks from last year’s Sony hack as another potential use-case.

“You as a person exist in a lot of places on the Internet, and I just feel that you have the right to at least know what’s out there, and to take care of it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com