This post is in partnership with History Today. The article below was originally published at HistoryToday.com.

‘I congratulate … [my fair countrywomen] on their present easy and elegant mode of dress’, wrote the surgeon James Nooth, in 1804, ‘free from the unnatural and dangerous pressure of stays.’ Nooth’s concern was not aesthetic. The danger he saw in restrictive bodices was cancer: ‘I have extirpated [removed] a great number of … tumours which originated from that absurdity.’

Breast cancer in the 19th century was a consistent, if mysterious, killer. It preoccupied many doctors, unable to state with any confidence the disease’s causes, characteristics or cures. While the orthodox medical profession in Britain were broadly agreed on cancer’s ultimate incurability, they were less uniform in their understanding of its origin. The disease was thought to develop from a range of harmful tendencies and events acting together. Both the essential biology of being female, as well as typically ‘feminine’ behaviors, were understood as causes of breast cancer.

Breastfeeding was a contentious topic at the end of the 18th century. An image of idealised motherhood emerged that infiltrated concepts of femininity: women were by nature loving, maternal and self-sacrificing. This ideology was expressed through changing social and political attitudes to breastfeeding and an outcry against wet-nursing across western Europe. In 1789 only 10 per cent of babies born in Paris were nursed by their own mothers; by 1801, this number had increased to half of all Parisian infants and two thirds of English babies.

Late 18th-century medical men were explicit about the associations between breastfeeding and breast cancer. In 1772, man-midwife William Rowley wrote: ‘When the vessels of the breasts are over-filled and the natural discharge through the nipple not encouraged … it lays the foundation of the cancer.’ Frances Burney – an aristocratic novelist who underwent a mastectomy in 1811 – attributed her disease to her inability to breastfeed properly: ‘They have made me wean my Child! … What that has cost me!’

Menstruation was seen as particularly hazardous. The surgeon Thomas Denman wrote: ‘Women who menstruate irregularly or with pain … are suspected to be more liable to Cancer than those who are regular, or who do not suffer at these times.’ However, their risk only increased after menopause. Denman considered ‘women about the time of the cessation of the menses’ most liable to cancer. Elderly women were blighted by a dual threat: their gender and their age. While surgeons insisted their theories were based on clinical observation, designating these various female-specific processes as causes of cancer supported their broader thoughts about female biology.

Eighteenth-century theory dictated that all diseases were explained by an imbalance in ‘humours’: black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm. Into the 19th century the insufficient drainage of various substances continued to be invoked as a cause of cancer; women’s ‘coldness and humidity’ made them particularly prone to disease. Menstruation was the primary mechanism by which the female body cleansed the system of black bile and its regularity was seen as central to a woman’s wellbeing. Certain situations in which the menses were disrupted or had been terminated were, therefore, especially dangerous: pregnancy, breastfeeding and menopause. Similarly, when the female body and its breasts were not used for their ‘correct’ purpose – childbearing and rearing – the risk of breast cancer increased.

The historian Marjo Kaartinen has noted that 18th-century theorists considered just ‘being female and having breasts’ a threat to a woman’s health. This way of thinking about female biology suggested that women were more likely to suffer from all cancers, not just cancer of the breast. Denman wrote: ‘It can hardly be doubted … that women are more liable to Cancer than men.’

This association between womanhood and disease and between breastfeeding, pregnancy, menopause and cancer is still part of our 21st-century understanding of breast cancer; that certain female-specific processes make you more or less likely to succumb to it. On its website, the breast cancer charity Breakthrough lists various ways you can reduce and increase your chances of disease. According to contemporary research, having children early and breastfeeding them reduces your risk. The later a woman begins her family the higher her risk is. The contraceptive pill, growing older and the menopause also increases your risk of breast cancer.

Drawing attention to such historical continuities questions the social and cultural environments that make certain medical assumptions possible. The causes of cancer suggested by Denman, Nooth and friends were informed by their understandings of female biology and female inferiority more generally. They were working within a school of thought that suggested any deviation from ‘appropriate’ womanhood could have hazardous consequences for a woman’s health. While the role of the historian might not be to deny the validity of 21st-century medical research, it is part of our remit to question cultural assumptions that continue to have some effect on both the conclusions of scientists and the way those conclusions are accepted by the broader public.

Agnes Arnold-Forster is a PhD candidate at King’s College London.

Sandy Cohen

Age 45, Pennsylvania

Age 36 at time of surgery

“I grew up knowing cancer was in my future. My grandmother died of breast cancer before I was born, and although my mother tried chemo and special diets, she passed away when I was 26.

As I started to near my 40s, I decided it was time for me to get tested for the BRCA mutation. Even though I had prepared for it my whole life, I was stunned when they came back positive. There’s something about hearing that you have an 87% chance of getting breast cancer and a 50% of getting ovarian cancer that you can never prepare for.

At that point, I decided I needed to do what my mother and grandmother hadn’t: get a double mastectomy. I felt lucky I had that choice. When I told family and friends about my decision, half told me I was extremely brave, and the other half thought I was nuts. But BRCA wasn’t really in the news yet. Angelina Jolie had not come forward about her experience. Even if other people did not understand, I needed to undergo the procedure. I thought about my kids, and how I couldn’t let cancer take me from them.

My mother was so quiet about her cancer experience, which is why I speak out. I will continue to be strong for my kids because I want them to be brave, too.”

Karen Kramer

Age 48, Maryland

Age 44 at time of surgery

“When I found out I was positive for the BRCA mutation, I didn’t cry. In fact, I have never cried about my BRCA mutation except when I think about my three children, and the fact that they each have a 50% of inheriting it. We talked about it as a family, and they are all aware of what it means for them as men and women. In many ways I wish I could unburden them with this information, but at least it means they’re not afraid.

I found <u><a href=”http://www.facingourrisk.org/”>FORCE</a></u>, Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered a nonprofit group for families dealing with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. I met such generous women who would take me to the bathroom over lunch to show me their reconstructed breasts so I wouldn’t be scared.

Some women don’t want to talk about their procedure, but as a woman in FORCE, I am now the vice president of marketing, I feel a responsibility to the next generation. I hold meetings for women considering prophylactic mastectomy, and like many women did for me, I lift my shirt for those who are frightened and confused. We are not disfigured, and although we have scars, the scars tell our story and they saved our lives.

Unlike many other predispositions, you can do something about the BRCA mutation. Only 10% of people with a BRCA mutation or at a high risk for it, know if they have it. The message has to get out there for the other 90% who could read an article or see a pamphlet and realize this could be them. Their life could be changed.”

Karen is pictured with her daughter Joanna, age 14.

Susan Lichten

Age 60, New York

Age 59 at time of surgery

“I remember screaming when the genetic counselor called to tell me I was positive, and my husband was right by my side-and never left.

He was with me for every appointment with the genetic counselor, every trip to the hospital, and every trip to the plastic surgeon. He was always asking questions, reading every article, and writing down all the statistics on my risk.

After my surgery he took care of me, helping me in the shower and getting dressed. I never had to worry that he would look at me differently after this surgery. Our wedding song was, “I Love You Just The Way You Are,” by Billy Joel, and he has shown me just how much he means it.”

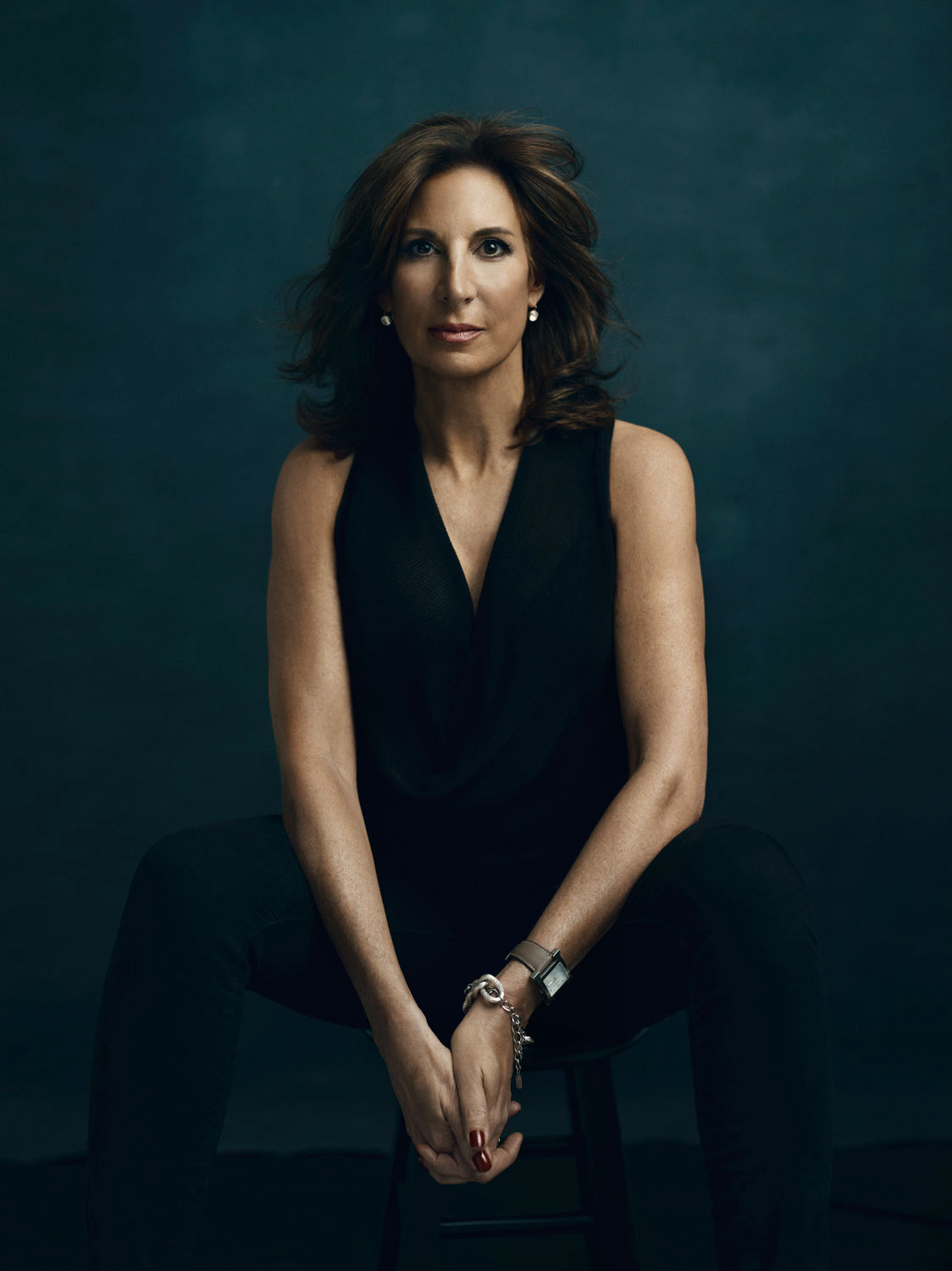

Lisa Schlager

Age 47, Maryland

Age 41 at time of surgery

“I was one of the first women to be tested for the BRCA mutation in 1999. I don’t have a glaring family history, but my aunt was diagnosed with breast cancer in her 40s, and enrolled in a study of Ashkenazi Jews with premenopausal breast cancer. She convinced me to participate, and I went in for testing. Back then it took three months to get results, but I wasn’t full of anxiety because I didn’t really think I would test positive. But when the genetic counselor called me to inform me I should come in for my test results, the tone of her voice told me everything.

At the time, I was in my early thirties, and I decided to put off drastic measures until after I had kids. But as I neared my 40s, I had to go in for a biopsy, and although it wasn’t cancerous, I suddenly felt less invincible.

I decided to get the bilateral double mastectomy and reconstruction with expanders, but in the couple of days leading up to the surgery, I started to panic. I called a friend who had breast cancer at the time, and she laid into me, saying, ‘you do not want to be like me. If I could do what you are doing, I’d do it in a heartbeat.’

Even though I was well prepared, after the surgery, you have feelings you don’t anticipate. I felt incredibly relieved, but also a sense of loss at losing body parts. It takes time to feel like yourself. My children have a 50% chance of carrying the gene mutation, and although my 10-year-old son is not ready to talk about it, my 13-year-old daughter is fully aware. She knows it’s not something we need to think about yet, but she’s not scared.”

Lisa is pictured with her daughter Rachel, age 13.

Marisa Moss

Age 40, New York

Age 37 at time of surgery

“I don’t regret my double mastectomy, but my decision is something I struggle with every day. I know I would constantly worry about cancer, always taking mammograms and ultrasounds and getting biopsied with every speck. I still struggle over it, but I don’t cry anymore.

I was tested as a potential BRCA carrier when I was 27 years old, and participated in a study of people at high-risk for breast cancer. For many years I opted for surveillance, with mammograms and ultrasounds. But one day, almost ten years later, my doctors spotted a potentially cancerous spot—it was only stage 0, and though I had some cancer in a cell, it still hadn’t permeated the cell wall. But I knew it was time to take action.

Deciding on the double mastectomy wasn’t easy. I was always petite and a size DD breast. For 20 years, my breasts were really a part of my identity: I was Marisa, the little girl with the big breasts. Thankfully my plastic surgeons made me look beautiful, but the fact I made a decision I could not go back on was so frighteningly finite.

In a way, I am different from some other women I share my experience with. I didn’t tell very many people, I didn’t post my change on Facebook and I didn’t visit support groups. While talking it out for some women is healing, for me, I don’t want cancer to define me. I work for an investment bank, and when I came back from surgery, I launched two tech companies. BRCA is one chapter in my life that is very important to me, but I healed by keeping it separate from who I am as Marisa Moss.”

Dr. Elizabeth Chabner Thompson

Age 45, New York

Age 38 at time of surgery

“The first time I was going to get my double mastectomy—I chickened out. I had signed the papers, and I was in for my last pre-operation check five days before my surgery, when I suddenly couldn’t bear to go through with it. I practically ran from the hospital. I was terrified, and I’m an oncologist.

My maternal great-grandmother and mother both had breast cancer, as did my paternal grandmother. In her earlier years, my great grandmother was a curvy model. But she underwent a Halstead radical mastectomy that removed her lymph nodes and it left her disfigured. After my mother got her mastectomy, she couldn’t look herself in the mirror. She couldn’t take her bandages off—I did it for her.

Although my mother and I actually test negative for the BRCA mutation, as an oncologist, I know there is some other gene that runs in our DNA we just haven’t identified yet. As a physician, I already knew too much and I wanted to be proactive. I knew I was a ticking time bomb.

When I told my friends about my upcoming procedure, some of them looked at me like I was crazy, like it was a brutal mutilation. They told me to just wait and see what happens, but I told them the idea of getting the breast cancer diagnosis and having chemo was something I couldn’t face. Maybe I was a coward, but I felt like at that point I still had a choice.

Since my procedure, I’ve launched my business, Best Friends For Life (BFFL Co) that provides patient hospital kits and a new surgical bra to help women recover in comfort. The ironic thing is that I thought that by having a prophylactic double mastectomy, I would rid myself of the space in my brain that was constantly occupied by worrying over breast cancer, but now my whole life is devoted to helping other women in my situation. And that feels right.”

Andrea Ziltzer

Age 50, New York

Age 46 at time of surgery

“My mother got cancer out of the blue, and although she had mammograms every year, by the time they found it, it had already spread and she died 14 months later. I remember one moment when she said to me, ‘wow, a mastectomy looks really good right now.’ But that was no longer an option.

I was against testing at first because I didn’t know what I would do with that information. I didn’t know how far along mastectomies had come. Ten years later, I decided to just go through with it, and when I came back positive for the mutation, I remembered my mother, and knew I was getting a double mastectomy.

I never doubted my decision. Besides a couple men I shared my decision with, no one ever questioned me. Everyone was supportive, including my children. My daughter is 22 now, and we’ve always been open about my choice. I don’t want women to be ashamed. There’s nothing we need to hide, which is why I tell my story.”

Andrea is pictured with her daughter Sydney, age 22.

Sara Roter

Age 35, New York

Age 29 at time of surgery

“I knew I made the right decision to get a prophylactic double mastectomy when the day before my surgery the hospital called to say my doctor broke his hand in a motorcycle accident, and had to postpone. When I felt genuinely upset instead of relieved, I knew I made the right choice—this was my way out.

I had waited two years after I found out I was BRCA1 positive to do anything about it, mostly because I didn’t know what to do. Genetic testing was still fairly new, and I didn’t know any women my age who had gone through it. But when I finally met with doctors, getting a double mastectomy was the clear decision for me. It wasn’t an easy decision, but it was the only one.

My husband was incredibly supportive. He was happy to let me cry, and also give me a kick in the butt to remind me that I was ok. He found the group Bright Pink for me, a non-profit organization focusing on risk reduction and early detection of breast and ovarian cancer in young women. There I met women who truly understood my decision and procedure.

I have two young daughters now, and I am thankful we have some time before they need to be burdened with BRCA testing. My hope is by that time, there might even be a cure.”

Randi Simson

Age 58, New York

Age 53 at time of surgery

“I knew a double mastectomy was the best option for me. But I’m a worrier. I was angry at the genetic counselor when she told me I had the BRCA mutation. I was recently divorced, moving into a new place, and this just wasn’t part of my recovery plan.

When you are having DIEP flap reconstruction as I did, tissue from your abdomen becomes your new breasts, so my surgeon encouraged me feel free to indulge in eating, so there’s more to work with during reconstruction. But my anxiety was so great I actually lost weight, and my surgeon was concerned I’d have to go down a breast size.

Although I was relieved after my surgery (and there was enough for normal reconstruction), it took me a while to come to terms with my new body. I didn’t regret the surgery, but occasionally I’d find myself wondering, what did I do? My breasts are numb, and that feels strange. I wore a strapless dress to my daughter’s wedding and I remember thinking, if this falls down, I will have no idea. One time I wore an underwire bra to work, and the wire was sticking out of my shirt. I didn’t notice until I went into the women’s restroom, and I just had to laugh.

As women, we are so often judged for how we look, and I don’t feel like this is my best. Sure, I am not in my 20s or 30s, but I’m very active and in my head, I’m still 23.”

Megan Olsen

Age 34, Illinois

Age 33 at time of surgery

“I was 32 when I found a lump, and decided to get it checked. I was shocked to learn I had cancer.

I was just finishing all my treatment when I decided to go through genetic testing. It was just a precautionary measure, since my doctors were concerned about my age. I learned I was BRCA2 positive, and had an incredibly high risk of getting breast cancer in my other breast. Once again, I felt like I was living a dream that I’d give anything to wake up from. It was February 2012 when I was diagnosed with the mutation, and by the next month, I had undergone my mastectomy.

Although I will be on Tamoxifen for another four to nine more years, I find myself here, alive, two years later, after having completed a lumpectomy, egg freezing, three months of chemotherapy, genetic testing that resulted in a positive BRCA2 gene mutation, a follow-up double mastectomy, and an extensive reconstructive process.

I’ve lost my hair, and on some days my dignity. I’ve wanted to scream and smash things for no reason, and I’ve never felt more sick or depressed in such a short timeframe. But for now, I have my life. I know why this happened to me, and I’ve done everything I can to prevent it from ever continuing. And there’s absolutely no price tag for a gift like that.”

Leah Feldman

Age 33, New Jersey

Age 29 at time of surgery

“I always tell women to prepare for that moment when you take off the bandages. It suddenly becomes very real. I didn’t want any family and friends there, so I asked one of the nurses to be with me when I looked for the first time.

Even though I was very emotionally prepared throughout my process—my positive BRCA1 results didn’t surprise me given my family history—seeing the aftermath of surgery was still upsetting. I took a couple minutes to cry with the nurse, and it felt very cathartic. After that, it was time to move on.”

Roberta Schloss

Age 60, New York

Age 54 at time of surgery

“My BRCA diagnosis hit me harder than when I found out I had cancer. When the genetic counselor told me I was BRCA1 positive, I felt like I was hit by a truck. I never really thought my results would be positive, and I was devastated.

For about a week, I sat staring at a wall before I decided to undergo my operation. I kept asking my genetic counselor to remind me of my stats—surgery cut my cancer risk by 80%. Tell me again, I’d say. During my 10-hour operation, I had my breasts removed, my ovaries removed, and my fallopian tubes removed. I said, just take it all. I couldn’t stop thinking, where is the cancer growing now?

The reconstruction was the most trying. Nurses came in every 15 to 30 minutes to feel my chest, and I just felt silly. I wasn’t trying to win any beauty pageants, and now my bras just suffocate me.

I know many women who have undergone my same surgery, and have become proud advocates for breast cancer. That’s not me. I don’t want to be the poster child for BRCA or breast cancer, but at the same time, it will always be a big part of me. My decision was terrifying, but I don’t regret it.”

Roberta is pictured with her daughter Hannah, age 30.

Debbi O’Shea

New York

Surgery in 2000

“The first thing I said when I found out I was BRCA positive was, ‘at least now I know why.’

I had been cancer-free for four years, but the cancer I beat had come seemingly out of nowhere. After all, I was only 37 when I was diagnosed. But on one fateful afternoon, my paternal aunt called to reveal a devastating family secret. My dad’s side of the family was riddled with breast and ovarian cancer, with at least seven members carrying the disease. I felt betrayed they hadn’t told me earlier; perhaps it was generational not to speak of such things. The medical community at that time didn’t place much weight on paternal history.

I had already beaten cancer—I wanted it to be over, but when I tested positive, my genetic counselor told me my likelihood of cancer recurrence in my breast was 65%. My family history was the worst she had ever seen.

So although my breasts had made it through cancer, I decided to electively remove them before they could turn on me again. I knew myself emotionally, and I couldn’t stand the years of constant anxiety if I chose surveillance. With the decision made, I immediately felt peaceful.

Although I kept my initial surgery under wraps—I didn’t want my son to worry—once I recovered, I took the strongest stance I could by blogging about my experience and speaking to crowds of women about my decision. It was a very lonely time when I made this choice, and to interact with kindred spirits helped me heal, and I want to return the favor.”

Ali Weinberg

Age 26, Washington, D.C.

Age 21 at time of surgery

“This wasn’t what I was expecting my senior year of college to be like. When my parents told me my dad carried the BRCA gene mutation, I wanted to get tested right away. When I met with the genetic counselor, she filled out my family tree, using triangles to represent the women of my family, and she shaded in black the ones with cancer. It felt very foreboding. When my results came back, the doctor told me my chances for breast cancer were 87%, and my risk of ovarian cancer was 44%.

Over spring break of my senior year, at age 21, I decided to get a double mastectomy and reconstructive surgery. If I could lower my risk to negligible and still have great boobs, the decision was obvious. Somewhat darkly, I thought it was ironic that girls my age were probably flashing their boobs on spring break while I was getting mine removed.

Before my first surgery, the hospital staff had to take medical photos of my chest. I remember looking at my breasts and seeing them for the first time as a part of me, and as a defining feature of the female body. I wondered, am I going to feel as beautiful as I do with my natural breasts? Will this be a problem in my dating life?

Thankfully, I had a phenomenal reconstruction team (I decided to go for a size upgrade as a little ancillary benefit), and I realized that my confidence and identity was not at all attached to my natural breasts. My view of myself was always more about my confidence and attitude than it was any physical part of my body. I feel more beautiful and empowered because I took control.”

Diane Rose

Age 45, Philadelphia

Age 40 at time of surgery

“After my aunt was diagnosed in her early 50s with stage 4 ovarian cancer and the BRCA mutation, my two brothers and my sister all decided we should get tested together. The four of us got our counseling together, we lined up together to get our blood drawn, and we returned together—with our parents and spouses–to get our results. Only my sister came back negative.

After learning my status, I decide to research my options. I went to a FORCE meeting where the women actually showed us their reconstruction in a private room and it was so helpful to see that everyone still looked so beautiful and whole. When I told my brother I was considering surgery, he told me, ‘Diane, it’s not a matter of if you’re going to do something, it is really a matter of when.’

The anxiety before the surgery is so intense, but when you wake up, you’re in a completely refreshed state of mind. As the anesthesia wares off, you experience a wave of relief and you think, ‘I did it. It’s done.”

Diane is pictured with her daughter Ellie, age 10.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com