Born from what TIME described in 1970 as a casual suggestion by Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, Earth Day was meant as neither protest nor celebration, but rather as “a day for serious discussion of environmental problems.”

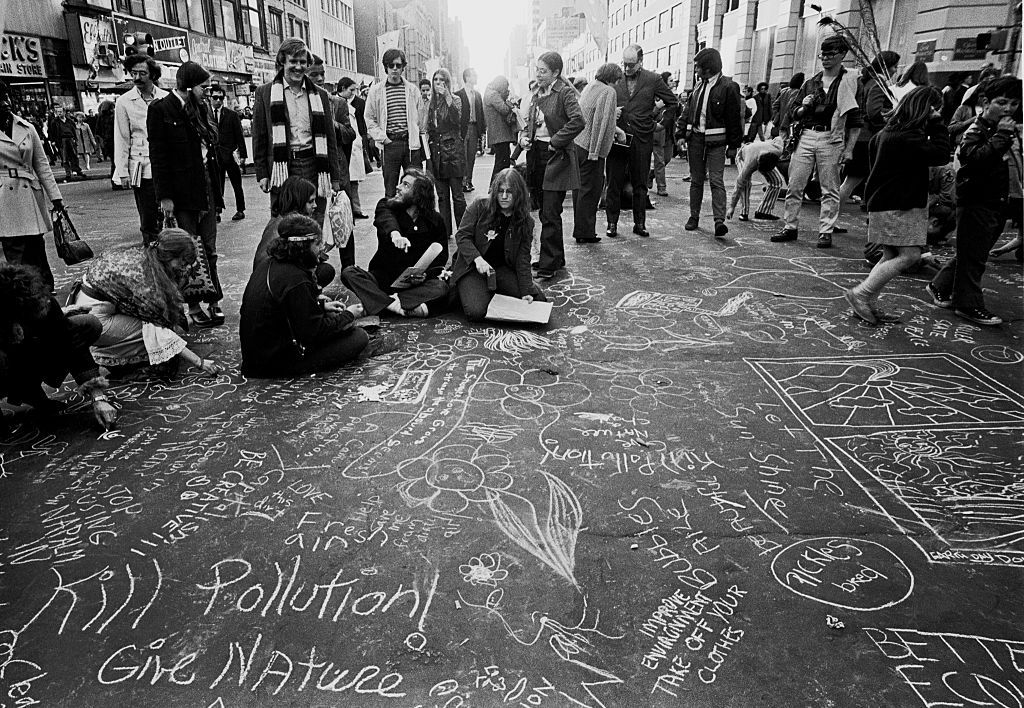

What surprised Nelson — and others — was how much enthusiasm the idea engendered. On April 22, 1970, nearly 20 million Americans took Nelson up on his suggestion and turned out for the inaugural Earth Day events. These cropped up all over the country, on college campuses and in public places — including Central Park and New York’s Fifth Avenue, which was closed to traffic for two hours while 100,000 people staged a quiet, contemplative parade.

A dissonant combination of festivity and somber reflection pervaded the holiday. Environmentalists found themselves transformed into celebrities for a day, suddenly overrun with invitations to share their grim prognoses for the planet. As TIME wrote in 1970:

Ecologist Barry Commoner’s schedule was the busiest, calling for him to rush from Harvard and M.I.T. to Rhode Island College and finally to Brown University. Population Biologist Paul Ehrlich was lined up for speeches at Iowa State, Biologist René Dubos at U.C.L.A., Ralph Nader at State University of New York in Buffalo. In addition, such heroes of the young as Dr. Benjamin Spock, Poet Allen Ginsberg and various rock stars planned to have their say, if not precisely about ecology, then about the joys of the natural life.

Along with educational lectures and nature walks, however, there were livelier, more dramatic demonstrations meant to draw attention to the need for environmental reform. According to the New York Times, some activists held “mock funerals of ‘polluting’ objects, from automobiles to toilets.” Per TIME, students at several schools collected piles of litter and then staged “dump-ins” on the steps of city halls and manufacturing facilities.

At San Fernando State College, a group of students offered rice and tea to passersby as a sample of the “hunger diet” they could expect in the future, when overpopulation led to worldwide famine.

Meanwhile, at Florida Technological University, some students held a mock trial for a Chevrolet charged with poisoning the air. Finding it guilty, they set about executing it with a sledgehammer — but according to TIME, “the car resisted so sturdily that the students finally shrugged and offered it to an art class for a sculpture project.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — their heavy-handed theatrics, these grassroots protests paid off. By the end of the year, Congress had authorized the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

By the following year, Earth Day had grown into Earth Week, and this time it was officially sanctioned by President Nixon. But the festivities were “cooler and saner” the second year, per TIME, which noted, “Instead of noisy confrontations, the 1971 ‘week’ that ended April 25 ran to practical matters, like arranging bottle pickups.”

Read more about the importance of the environment in 1970, here in the TIME Vault: Issue of the Year

See The Best Biology Photos Of The Year

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com