When Marco Rubio launched his presidential campaign Monday evening in Miami, it’s a safe bet the speech made a lot of Republicans remember why they dubbed him presidential material.

Nobody in the GOP can spin a yarn like the freshman Senator from Florida. Rubio’s bootstrap narrative, rhetorical flourishes and emphasis on American exceptionalism have made him one of the few national figures capable of bridging the chasms between the party’s grassroots base, billionaire donors and the Washington establishment.

These gifts were on display in Rubio’s announcement speech, which framed the 2016 presidential election as a clash between leaders “stuck in the 2oth century” and those looking toward the future.

“Yesterday is over, and we are never going back” he told supporters. “We must change the decisions we are making by changing the people who are making them.”

The question is whether now is Rubio’s time. For much of the past two years, it hasn’t looked that way.

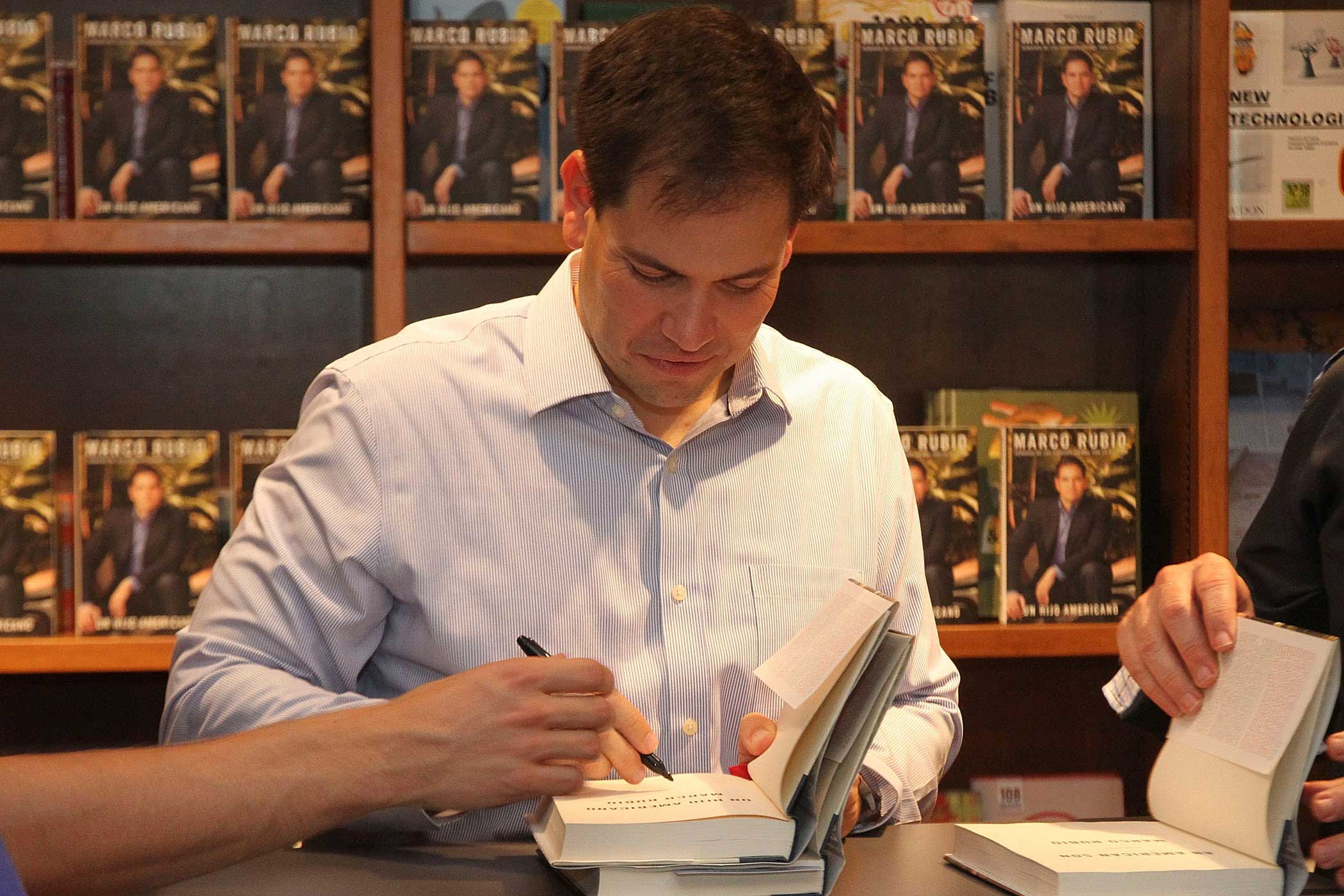

Rubio, 43, was a conservative sensation in 2013 when he joined a bipartisan group of Senators to craft a rewrite of U.S. immigration laws. (TIME put him on the cover, anointing him “The Republican Savior.”) Rubio became the face of the GOP effort to rebrand itself with Hispanics in the wake of an election in which they got clobbered in the contest for the nation’s fastest-growing demographic group, winning just 27% of the Latino vote.

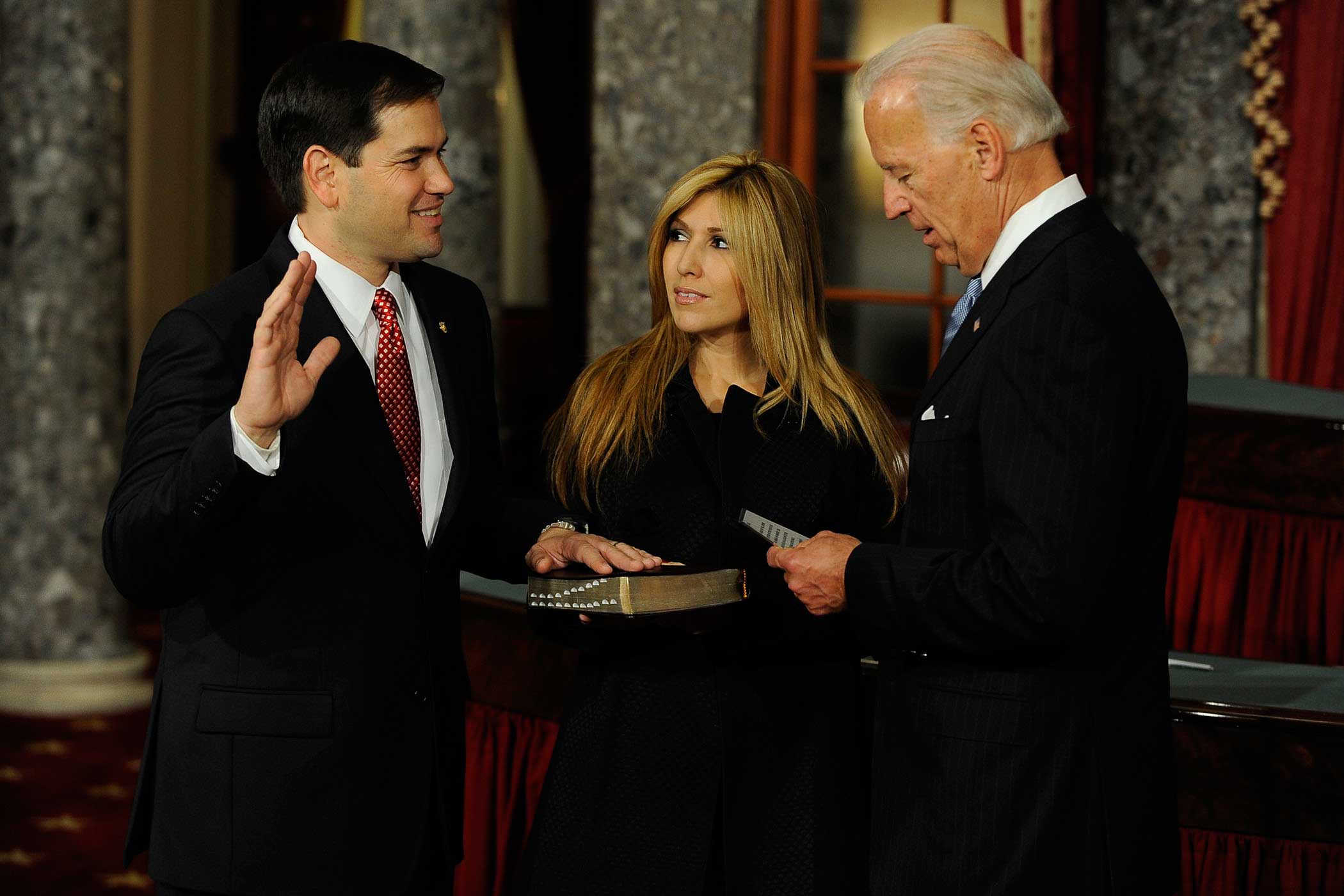

The gamble backfired. Comprehensive immigration reform collapsed amid a revolt from conservatives, who were incensed by a deal they decried as “amnesty.” And Rubio, whose upset Senate victory in 2010 was driven by Tea Party activists, was left to labor offstage as his presidential rivals vacuumed up money and hype.

His comeback strategy was simple. Rubio adopted an intentionally low profile as he repaired his relationship with the party base. In Washington he focused his efforts on foreign policy, returning to his roots as one of the Senate’s pre-eminent hawks. And he quietly wooed bigwig donors in small meetings and private conferences, nurturing a small yet loyal cadre of backers.

Rubio’s plunge into the 2016 pool will make a splash. But don’t be surprised if he soon returns to the low-profile approach on the campaign trail. There will be visits to early states and countless meetings with donors, but Rubio doesn’t expect to rocket to the front of the primary pack anytime soon. A protégé of former Florida governor Jeb Bush, Rubio can’t match the fundraising prowess of the son and brother of Presidents. (His jab at Democratic front runner Hillary Clinton Monday as “a leader from yesterday” appeared to be a shot at Bush as well.) Nor can he squash Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s surge in Iowa and New Hampshire.

Instead Rubio’s path to the party’s nomination relies on running a lean, upbeat campaign that blooms late, advisers say. At this stage, being a lot of voters’ second choice can be a first-rate strategy. The campaign hopes the base never warms to Bush, its romance with Walker proves fleeting and the social-conservative vote is divvied up between the various candidates vying for it. Then Rubio’s lean campaign operation will expand rapidly, and he can capitalize on his personal magnetism through the platform provided by the presidential debates. Rubio aides point to the roller-coaster GOP primary in 2012 as evidence that strategy can work.

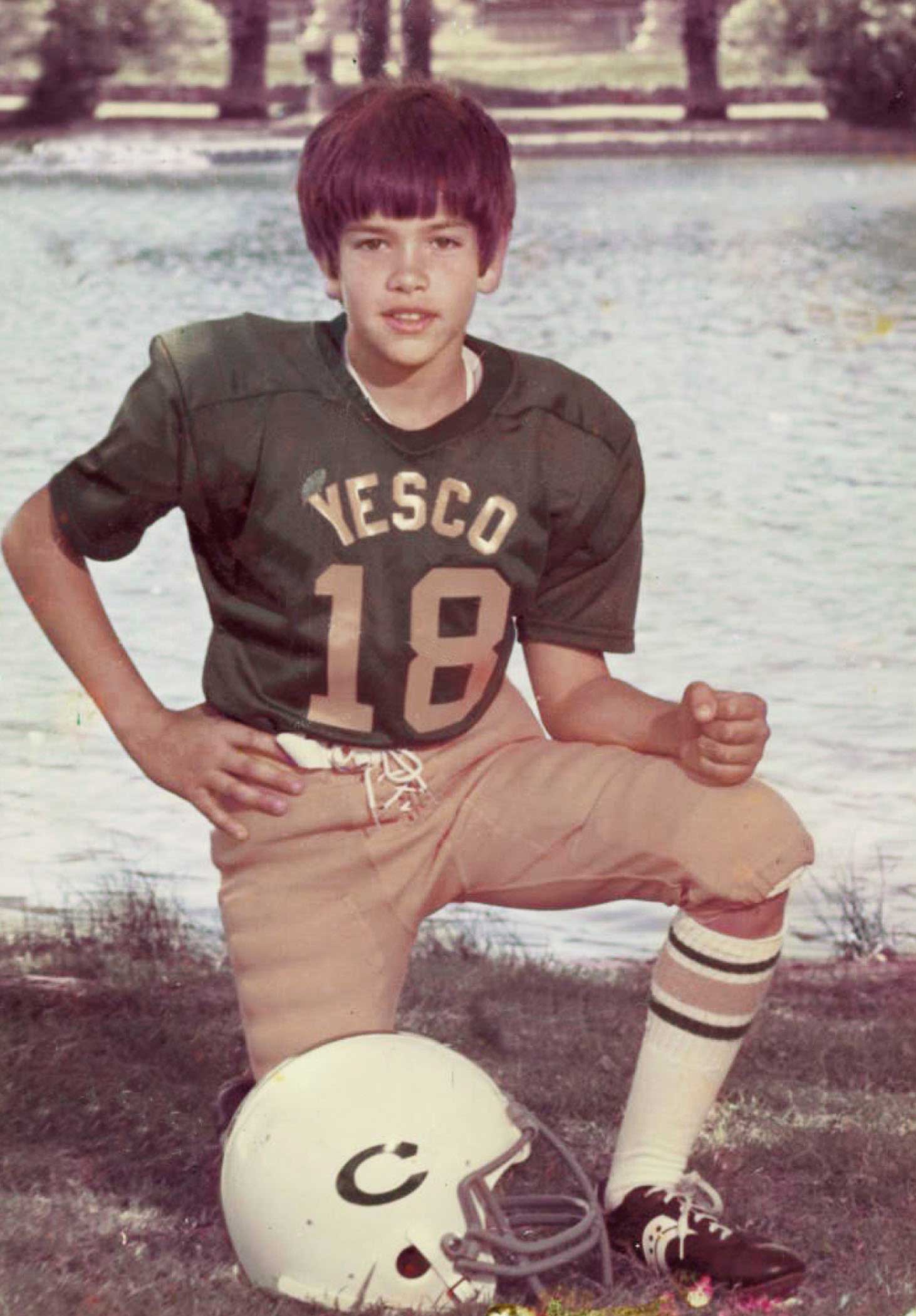

Rubio has never lost an election, and his gifts as a candidate are easy to spot. In a race dominated by scuffed dynasties, he offers optimism and freshness: a youthful face who can connect with new constituencies by speaking Spanish, talking football and quoting rappers. In a party of aging white guys, a 43-year-old Hispanic who hails from a top swing state carries certain benefits.

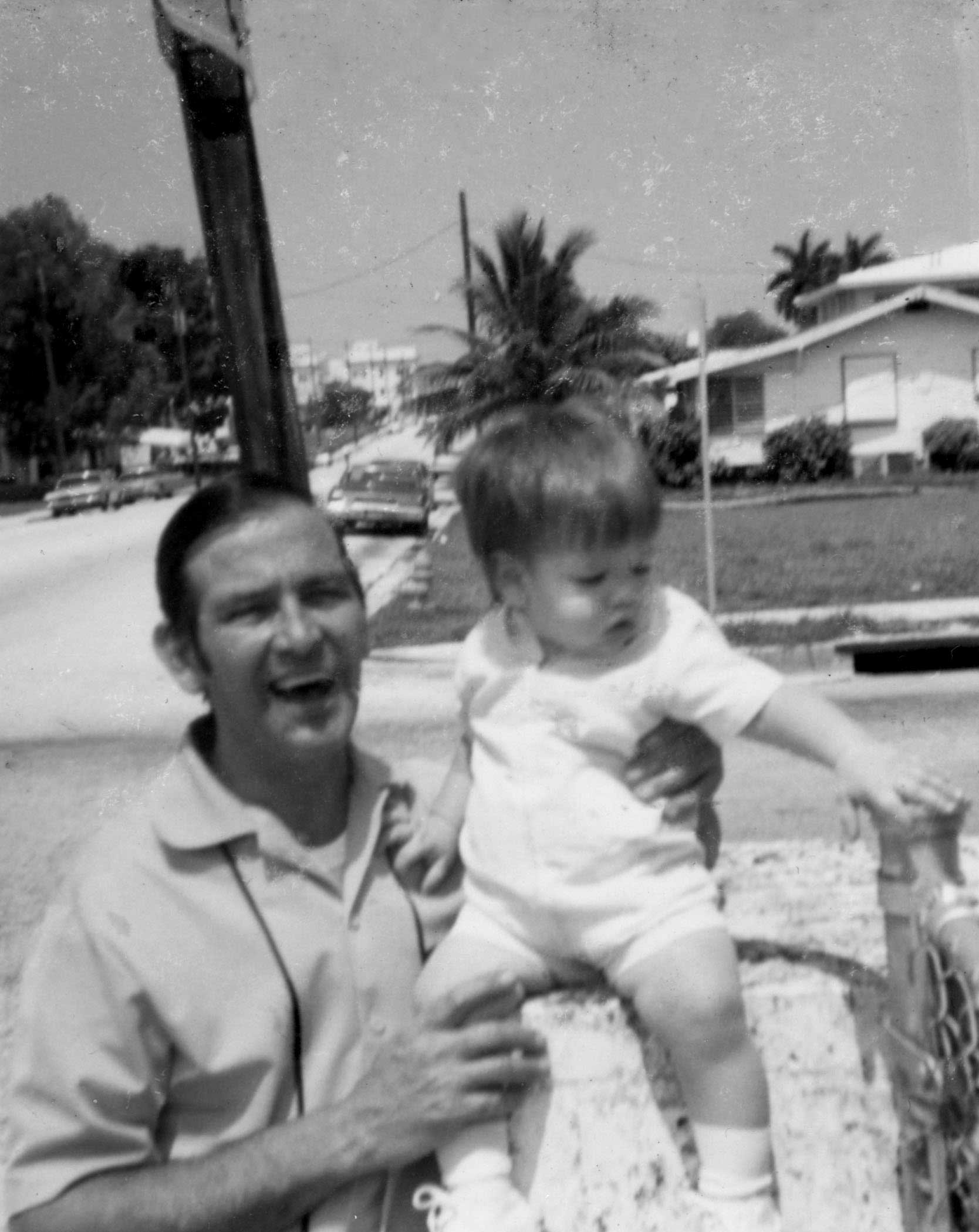

The son of Cuban refugees will lean heavily on his biography. Rubio’s mother made a living as a hotel maid; his dad worked as a bartender. Their son called the journey from serving drinks in the back of the room to announcing a presidential campaign at the front of one “the essence of the American dream.”

His announcement at Miami’s Freedom Tower, the so-called Ellis Island for thousands of Cuban refugees — “a symbol of our nation’s identity as a land of opportunity,” Rubio said — highlights the role that his personal narrative will play in his pitch. And Rubio’s campaign will rely on his charisma: polls show his approval ratings among the highest in the party.

This strategy is a proven winner at the presidential level, but perhaps not in a way that Rubio’s backers are eager to point out. As a freshman Senator with a minority background, a compelling personal story and dazzling oratorical chops, Rubio is the closest thing in the Republican Party to Barack Obama. At this time in 2007, Obama was an underdog, polling well behind the Clinton juggernaut. His victory illustrates the viability of Rubio’s strategy.

At the same time, the GOP has spent the past seven years decrying Obama as a nice guy with a light résumé who proved to be out of his depth in the Oval Office. The challenge for Rubio will be to bottle Obama’s campaign magic without reminding them too much of the man he’s seeking to succeed.

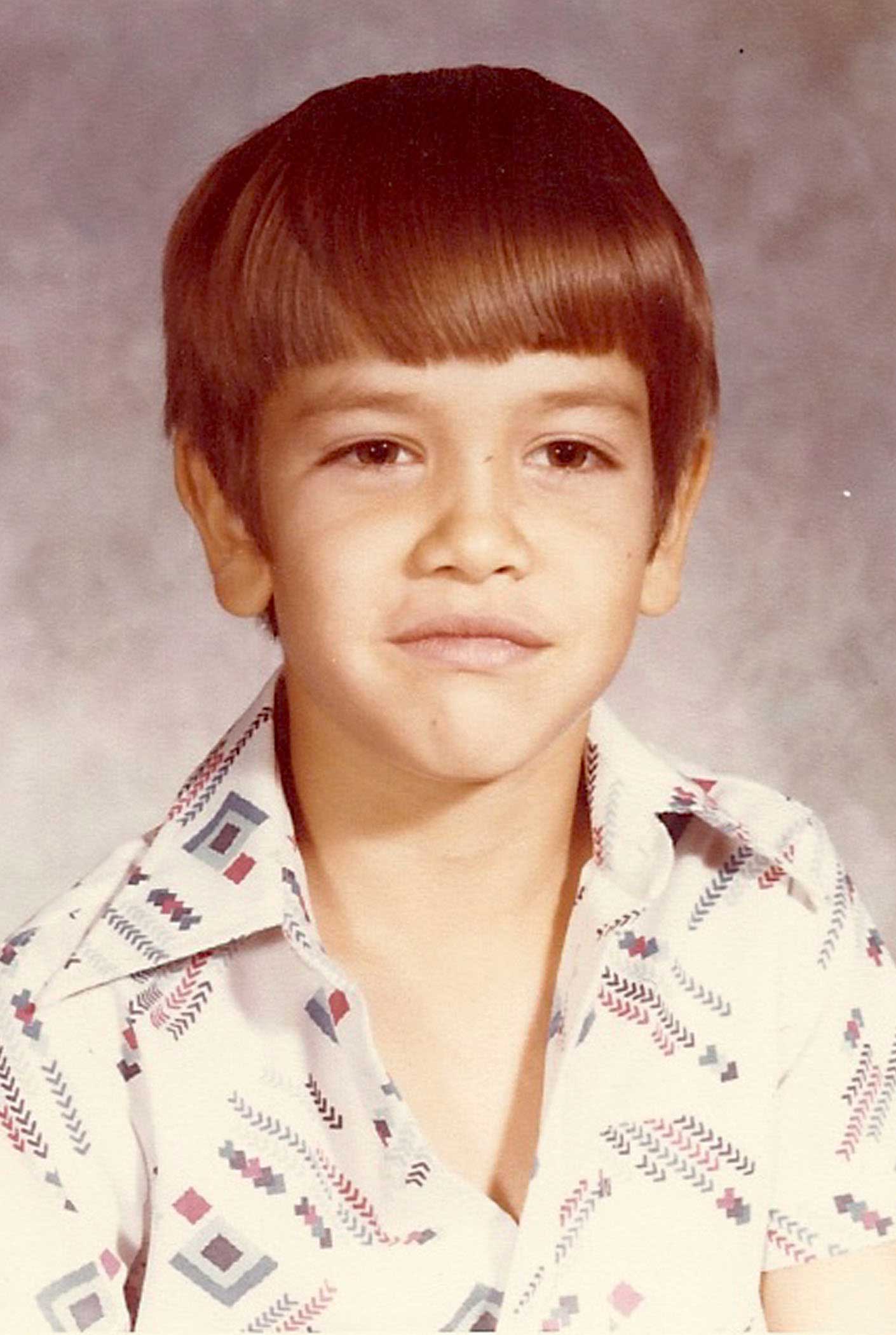

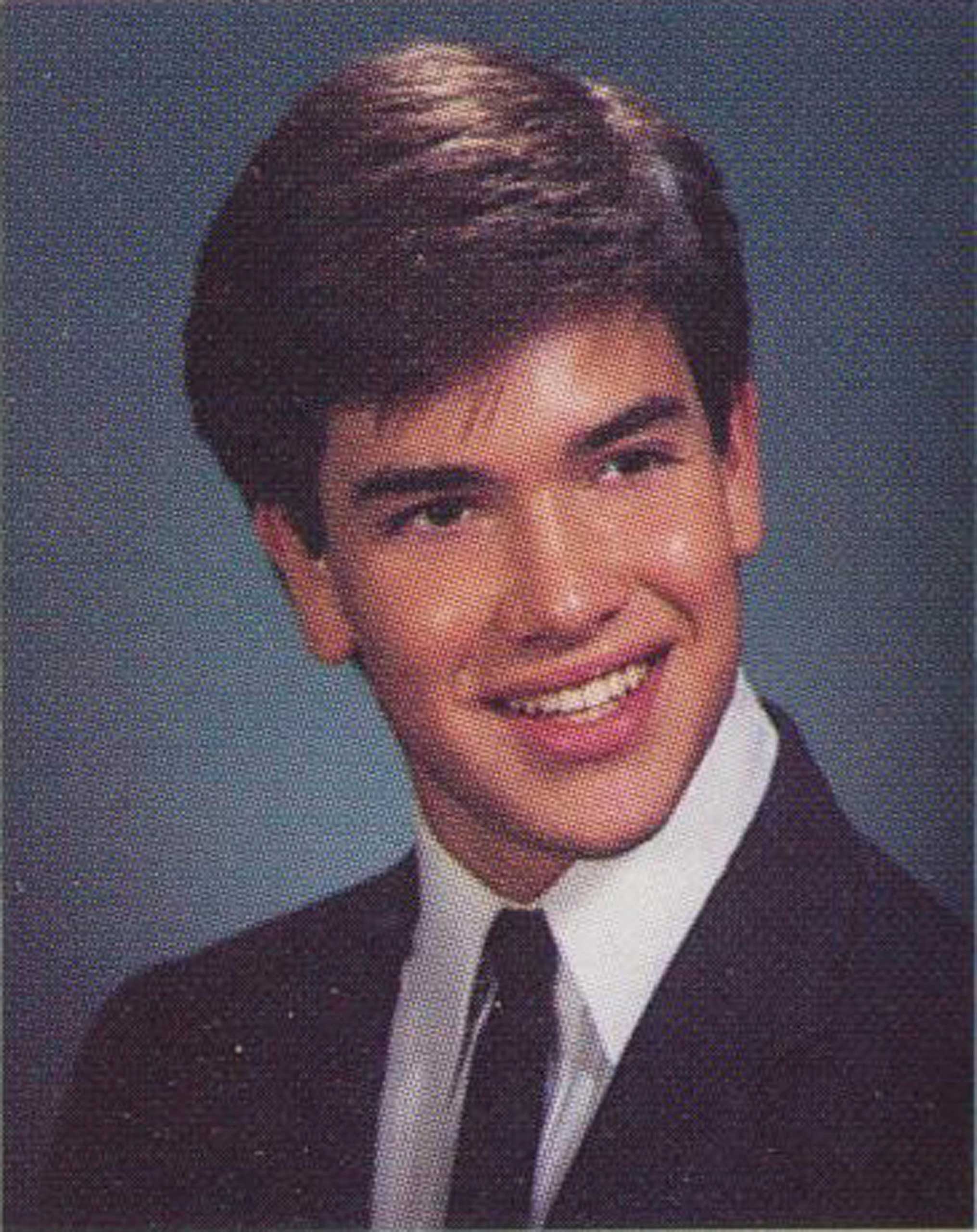

Marco Rubio's Life in Pictures

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com