This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

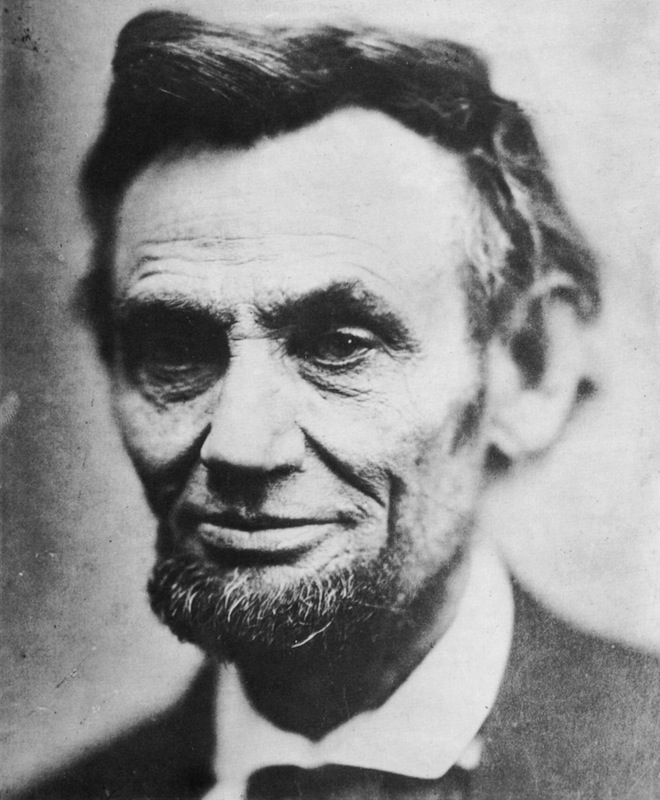

When Nelson Mandela died in 2013, news headlines called him “the Lincoln of Africa.” It is little wonder that modern journalists would make such a connection. Even today, 150 years since his untimely death at Ford’s Theatre, Abraham Lincoln’s legacy still looms large throughout the world. The comparison of these two men is an apt one. Both fought to bring freedom to their respective countries. Of equal importance, both sought to bring healing and unity to populations that were viciously divided over matters of race and social inequality.

In his second inaugural address in 1865, Lincoln famously called for “malice toward none” and “charity for all.” But he also implored his fellow citizens to act “with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right” to “strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds,” and “to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.” In calling for adherence to “the right” and a “just” peace, Lincoln was demanding that Americans admit the wrong of slavery and turn away from their national sin. Only then could the nation be at peace with itself and the world.

Nelson Mandela echoed these sentiments in his own inaugural address in 1994. “We commit ourselves to the construction of a complete, just and lasting peace,” he declared. Moreover, Mandela hoped to build a “society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.”

Like Lincoln, Mandela hoped to offer charity and forgiveness for his adversaries—but they, too, had to repent of their wrongs. Rather than punish his former white oppressors in mass trials, Mandela established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Those who had inflicted the Apartheid regime upon black and Colored South Africans would confess their sins, and those who had suffered would forgive. There would be malice toward none and charity for all.

Mandela was not the first prominent South African to appeal to Lincoln. In the classic novel, Cry, the Beloved Country (1948), Alan Paton employed Lincoln as a symbol of hope and equality, reconciliation and transformation. One central figure in the novel has four pictures in his study—one of Christ on the cross, one of Lincoln, and two depicting outdoor scenes. On one bookcase near the Lincoln picture are “hundreds of books, all about Abraham Lincoln.” The power of Lincoln’s speeches transforms several characters in the novel. If only more South Africans—in real life—could have read his words. In 1948, South Africa was careening toward Apartheid. Lincoln offered a better path, but the leaders in Pretoria ignored the better angels of their nature. Much bloodshed and injustice would soon follow.

As a young man in the 1940s, Nelson Mandela had his own unique encounter with Lincoln. While a student at the University of Fort Hare, Mandela joined a drama society that put on a play about Lincoln. The leading role went to another student who was appropriately named Lincoln Mkentane. Mandela played John Wilkes Booth. How strange to think of a young Madiba portraying one of the world’s most notorious villains! Yet Mandela took a particular lesson and inspiration from the experience. “My part was the smaller one,” he wrote in his memoir, Long Walk to Freedom (1994), “though I was the engine of the play’s moral, which was that men who take great risks often suffer great consequences.”

At first glance, Mandela could have been describing Booth—“the engine of the play’s moral”—who died twelve days after taking a great, if still somewhat cowardly risk, by shooting President Lincoln from behind in a dark theater. But of course Mandela was actually talking about Lincoln.

Lincoln took “great risks” to save the Union and free the slaves—to make the nation, as he once put it, “forever worthy of the saving.” On George Washington’s birthday in 1861, Lincoln declared at Independence Hall that he “would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender” the principles of the Declaration of Independence. Those principles, Lincoln said, gave “liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance.”

Lincoln would die for those ideals on April 15, 1865. A century and a half later he continues to serve as a symbol of America’s founding principles of liberty, equality and government by consent. But his modern connection to other great leaders like Mandela reveals how his legacy has spread, “not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time.”

Jonathan W. White is teaches American Studies at Christopher Newport University. His latest book is “Lincoln on Law, Leadership, and Life” (March 2015).

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com