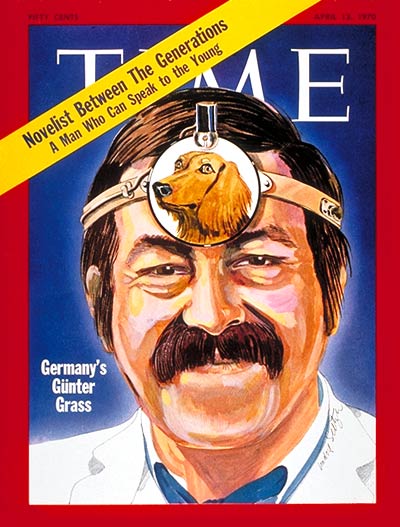

Günter Grass—the German writer who died on Monday at 87—was known for much of his life for the success of his books, for his Nobel Prize, for his defining place in the conflicted cultural world of the divided post-war Germany. In later years,his admission that he had served in the Waffen-SS and his publication of a poem critical of Israel changed his reputation.

As an April 13, 1970, TIME cover story about the author—dated precisely 45 years before his death—pointed out, Grass had made his name partially for his willingness to blur the line between art and politics, a line that had been strictly observed by traditional German literature. In the West Germany of the time, he was an outspoken supporter of Willy Brandt; his work was often seen as an admonition to those who would sweep the country’s past under the rug in the name of moving forward. “He too has done his demonic best to break up all the going German rhythms, from the marching-to-destiny beat of Deutschland über Alles to the amnesiac waltz of postwar prosperity,” the piece said, comparing him to the protagonist of his most famous work, The Tin Drum. “In three war novels he has drummed: Remember! Remember! REMEMBER!”

Even then, Grass did not deny that he was involved with the Nazi party during the war. And as the article laid out, he was a true believer, not merely going along to get along:

Grass has succinctly outlined his own journey into that nightmare: “At the age of ten, I was a member of the Hitler Cubs; when I was 14, I was enrolled in the Hitler Youth. At 15, I called myself an Air Force auxiliary. At 17, I was in the armored infantry.” Grass left Danzig as a soldier in 1944. He was wounded on April 20, 1945, and the end of the war found him in a hospital bed at Marienbad. He was one of the first Germans to be marched through Dachau for a whiff of what the infernal was really like. He has not forgotten.

…Call those the live-or-die years. Grass characters are nothing if not survival artists, and Grass survived. He estimates that 80% of the Danzig he knew was bombed out. He had to abandon, naturally, the patriotic ideology he once held as a self-styled “dutiful youth.” Like Mahlke, the schoolboy hero of Cat and Mouse, he once could identify most German warships by class. Unlike Mahlke, Grass admits: “I myself was thinking right up to the end in 1945 that our war was the right war.”

How did a grocer’s son from Danzig ever put together the nerve, the innocence, the cold fury, the sheer talent to play tin drummer to the most traumatic decade in modern history? The general pattern was one of slow maturing and lots of retreat time in the desert—the training rules of artists and saints.

At the time, despite that past, his intellectual evolution earned him a comparison to a saint; his political stance allowed the world to see him as an example of how the nation could properly acknowledge and progress from its Nazi past. But his “succinct” version of his time during the war years glossed over the extent of his involvement, which he eventually revealed in his 2006 memoir.

Considering he had made his name urging his country to remember—for example, that cover story pointed out, in his 1963 Dog Years he had written of “magic spectacles that allowed postwar German children to see exactly what their innocent parents were actually doing between 1939 and 1945″—the fact that he had did not completely described his own history earlier was devastating to his reputation. Amid the outrage, Grass said that he was still coming to terms with the past during those intervening years. When TIME lauded his “slow maturing,” that process had still been unfinished.

Read the full story, here in the TIME Vault: The Dentist’s Chair as an Allegory of Life

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com