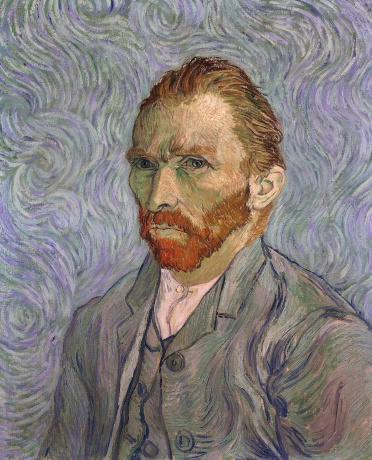

The anthology Ever Yours: The Essential Letters, contains 265 of Vincent van Gogh’s letters, which is nearly a third of all the surviving letters he penned.

In a long and winding letter to his brother Theo dated Thursday, 24 June 1880, van Gogh shines light on his independent mind.

Now one of the reasons why I’m now without a position, why I’ve been without a position for years, it’s quite simply because I have different ideas from these gentlemen who give positions to individuals who think like them.

Later, in the same letter, he defines two types of idlers.

I’m writing you somewhat at random whatever comes into my pen; I would be very happy if you could somehow see in me something other than some sort of idler.

Because there are idlers and idlers, who form a contrast.

There’s the one who’s an idler through laziness and weakness of character, through the baseness of his nature; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one. Then there’s the other idler, the idler truly despite himself, who is gnawed inwardly by a great desire for action, who does nothing because he finds it impossible to do anything since he’s imprisoned in something, so to speak, because he doesn’t have what he would need to be productive, because the inevitability of circumstances is reducing him to this point. Such a person doesn’t always know himself what he could do, but he feels by instinct, I’m good for something, even so! I feel I have a raison d’être! I know that I could be a quite different man! For what then could I be of use, for what could I serve! There’s something within me, so what is it! That’s an entirely different idler; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.

In the springtime a bird in a cage knows very well that there’s something he’d be good for; he feels very clearly that there’s something to be done but he can’t do it; what it is he can’t clearly remember, and he has vague ideas and says to himself, ‘the others are building their nests and making their little ones and raising the brood’, and he bangs his head against the bars of his cage. And then the cage stays there and the bird is mad with suffering . ‘Look, there’s an idler’, says another passing bird — that fellow’s a sort of man of leisure. And yet the prisoner lives and doesn’t die; nothing of what’s going on within shows outside, he’s in good health, he’s rather cheerful in the sunshine. But then comes the season of migration.

Ever Yours: The Essential Letters sheds light on the turbulent and beautiful life of history’s greatest luminaries.

This piece originally appeared on Farnam Street.

Join over 50,000 readers and get a free weekly update via email here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com