Correction appended, April 10

On a clear Saturday morning in North Charleston, S.C., a police officer drew his .45 caliber Glock service sidearm, braced his arms in a shooter’s stance, drew a bead on a fleeing suspect and fired.

Not once. Not twice. Eight times. The sound was almost like a string of firecrackers. Pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop. Then, after the briefest of pauses, one more pop. Somehow, Walter Lamer Scott, 50, managed to keep moving away from the lead hailstorm, but the last shot finally crumpled him. He died a short time later with multiple bullets in his back.

We know all this because millions of people carry smartphone cameras, and one of them was standing on the other side of a chain-link fence. We also know that the officer, Michael Thomas Slager, is a white man of 33. And that Scott was an unarmed black man whose brake light was malfunctioning.

These bits of knowledge add up to something catalytic in America’s painful examination of the way black men are treated by law enforcement. What happened across the fence from that video camera was the thing in its ugliest form: a man running away, an officer in no apparent danger, an unrestrained use of force. After the man was down, the officer appeared to place something–perhaps the officer’s Taser–beside the dying body. When the video surfaced three days after the April 4 killing, Slager was arrested and charged with murder, a crime punishable in South Carolina by life in prison or the death penalty.

“Where would we be without that video?” attorney Justin Bamberg wondered on behalf of Scott’s family. The answer to that question is important. Before the video emerged, the killing of Walter Scott had occupied the same contested territory in which hundreds of other cases have languished and festered–famous cases, like the killings of Eric Garner in New York and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and other cases that barely register in the police blotter. Slager told investigators that after he sought to question Scott about his brake light, the encounter somehow escalated. Scott, it was reported, had a warrant out for his arrest over delinquent child-support payments. The two men wrestled over Slager’s Taser, the officer said, and Slager felt threatened.

The routine encounter that gets out of hand, the abrupt escalation from questions to gunfire–the themes are so common that it’s hard to avoid two conclusions, which sit uncomfortably together in the American mind. First, that it must be scary to be a police officer in such circumstances. And second, that it is even more frightening–with an overlay of humiliation–to be the black man in the picture.

Walter Scott’s brother Anthony has struggled with the toxic reality that “you go from a traffic stop to someone being killed. It just didn’t make any sense to me, no sense to me at all, none at all,” he said in an interview with TIME. His brother was a forklift driver and a fan of the Dallas Cowboys, he said. Though Scott had been arrested about 10 times over the years, mostly for missing court hearings and failure to pay child support, he was a loving father to his four children, according to his brother. “He wanted to rent an RV and take all four of his kids on a cruise, and he wanted to take them to Disney World.”

Anthony said he was at a vigil for his brother when “a gentleman came over to me and said he had something to share with me.” The man pulled him aside and showed him the video he had taken. “I was angry. Shocked. And knew that we had to have it so that we could prove that he was innocent.”

Meanwhile, the outcome for Slager is impossible to know. Though he was being held without bail, though he was denounced by officials from South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley to Senators Lindsey Graham and Tim Scott, though his own lawyer dropped his case and North Charleston Mayor Keith Summey said flatly that the shooting was “wrong,” it remains difficult to convict a police officer in many jurisdictions. Communities ask a lot of the men and women who patrol the line between order and lawlessness; in return, the public tends to cut them a lot of slack. A recent analysis by the State newspaper in Columbia, S.C., found that officers in the Palmetto State fired their weapons at 209 suspects from 2010 to 2015, but the handful of cops who were charged with illegal shootings were eventually exonerated. A grand jury declined to indict the officer involved in the choking death of Garner, despite video of the victim rasping, “I can’t breathe!” as the cop maintained his throat hold.

Still, the North Charleston video has already put an exclamation point on the assertion made by protesters across the country that the dead are not always to blame. There are good ways and bad ways, right ways and wrong ways, to exercise the duties and powers of a police officer. When things go wrong–as they do with distressing frequency when white cops stop black suspects–sometimes it is the officer’s fault.

It’s possible, then, that the shooting in South Carolina (the third police-related shooting in the state involving white officers and unarmed black suspects since February of last year) will advance the issue from the realm of argument to the search for solutions. One place to start is inside police departments, where the impulse to close ranks now threatens to poison the reputation of law enforcement.

“People want to make generalizations that cops get away with stuff most of the time. No, they don’t. Most of the time their uses of force are appropriate,” says Delroy Burton, chairman of the Washington, D.C., police union. “But now, every single case of deadly use of force, particularly where race is a factor, it automatically becomes racism, and that’s just not true … The fact that officers now are guilty until proven innocent, or the force is inappropriate until an investigation is done–I think that sends a bad message to police officers, and I think it’s a waste of resources for society in general.”

And yet, there is a gap between Slager’s story to the cops and what appears on the video. As Chris Stewart, another lawyer for the dead man’s family, put it after the murder charge was filed, “What happened today doesn’t happen all the time. What if there was no video?”

Enlightened law enforcement leaders are coming to understand that the best path forward is more video, not less. The day after the murder charge was filed, Charleston police officials expanded on a plan to add about 100 body-mounted cameras to officers’ gear; in the aftermath of the video’s release, they promised to add 150 more cameras and said all city cops would eventually wear one. Of course, dashboard and body cameras should be the friends of well-trained, honest cops. The good apples are able to rely on more than their own word when they find themselves in trouble. The bad apples feel less free to level their weapons with impunity. Video is a tool by which the police can better police themselves.

The anguish over the troubled relationship between police departments and black citizens is national in scope. But there is relatively little that the federal government can do to solve the problem. The Department of Justice is seeking greater power to bring civil rights actions where they might be warranted–but this is, by its nature, an after-the-fact answer. Mending the relationship must take place town by town, department by department. “You’ve got over 18,000 local police agencies,” says Tanya Clay House, public policy director at the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “Not every one’s leadership is going to acknowledge the responsibility they have, and deal internally with the culture that’s present in their agency. But I do hope that this is a reality check.”

The shocking nature of the South Carolina shooting, so vividly captured on the video, ought to put police departments on the same side with the protesters who are demanding change. Everyone would benefit from less suspicion and fear. Everyone shares an interest in better training and technology to reduce the number of times the gun comes out of the holster. Everyone would be happier in a climate of trust among police and the public. No matter who you are, if you’ve seen Walter Scott gunned down, you now know what the problem looks like. Senseless and tragic, it is nonetheless a step toward solutions.

–WITH REPORTING BY JOSH SANBURN AND JUSTIN WORLAND/NEW YORK CITY AND ALEX ALTMAN AND MAYA RHODAN/WASHINGTON

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described the outcome of an investigation into the death of Eric Garner. A grand jury declined to indict the police officer involved.

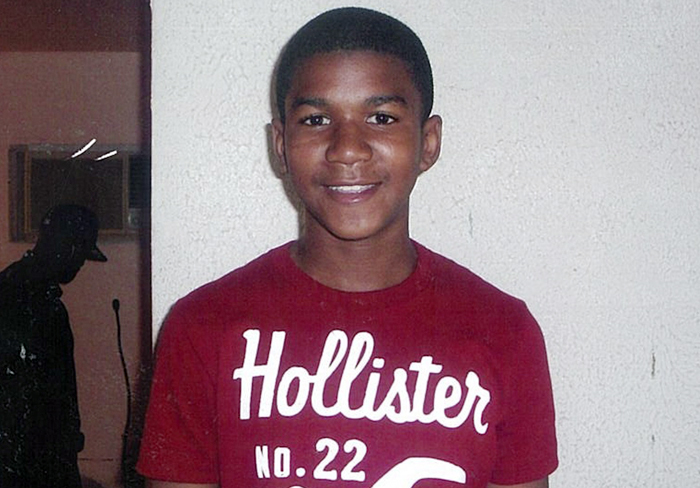

Trayvon Martin

Feb. 26, 2012 Neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman fatally shoots unarmed 17-yearold Trayvon Martin after an altercation in a Sanford, Fla., subdivision. The incident sparked a national conversation about race and prompted President Obama to say that were he to have a son, “he’d look like Trayvon.” Zimmerman, who argued that he acted in self-defense, was acquitted of second-degree murder and manslaughter in July 2013.

Ernest Satterwhite

Feb. 9, 2014 Ernest Satterwhite, 68, is shot and killed in his driveway by a white public-safety officer in North Augusta, S.C., following a slow-speed car chase. Justin Craven fired multiple rounds through the driver-side door of the vehicle. The officer alleges that Satterwhite reached for his weapon; Satterwhite’s family disputes the allegation. Craven was charged with a felony for discharging his gun into an occupied vehicle on April 7, the same day Michael Slager was charged with murdering Walter Scott. He faces up to 10 years in prison.

Dontre Hamilton

April 30, 2014 Milwaukee police officer Christopher Manney fatally shoots Dontre Hamilton, an unarmed 31-year-old African American with a history of mental illness, in a downtown park. Manney alleged that Hamilton, who appeared to be homeless, attempted to grab his baton during a pat down. Manney says he shot Hamilton 14 times in self-defense. Manney was fired in October but was not charged in the shooting.

Eric Garner

July 17, 2014 Eric Garner, 43, dies after being wrestled to the ground as New York City police attempted to arrest him for selling illegal cigarettes. In a cell-phone video recorded by a bystander, Garner can be heard repeatedly saying, “I can’t breathe.” The phrase was soon adopted as a rallying cry by protesters. On Dec. 3, a grand jury decided not to indict NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo in Garner’s death.

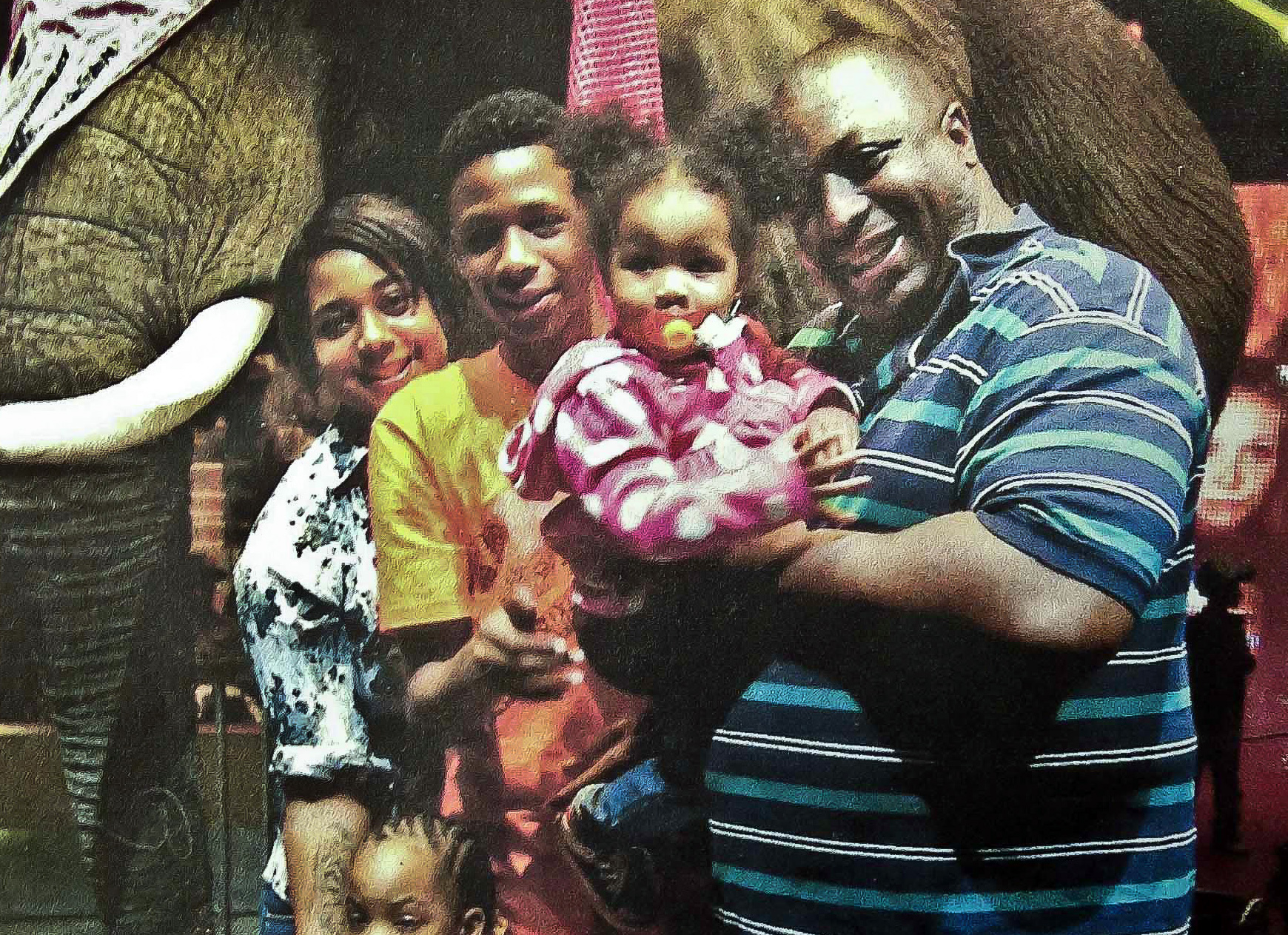

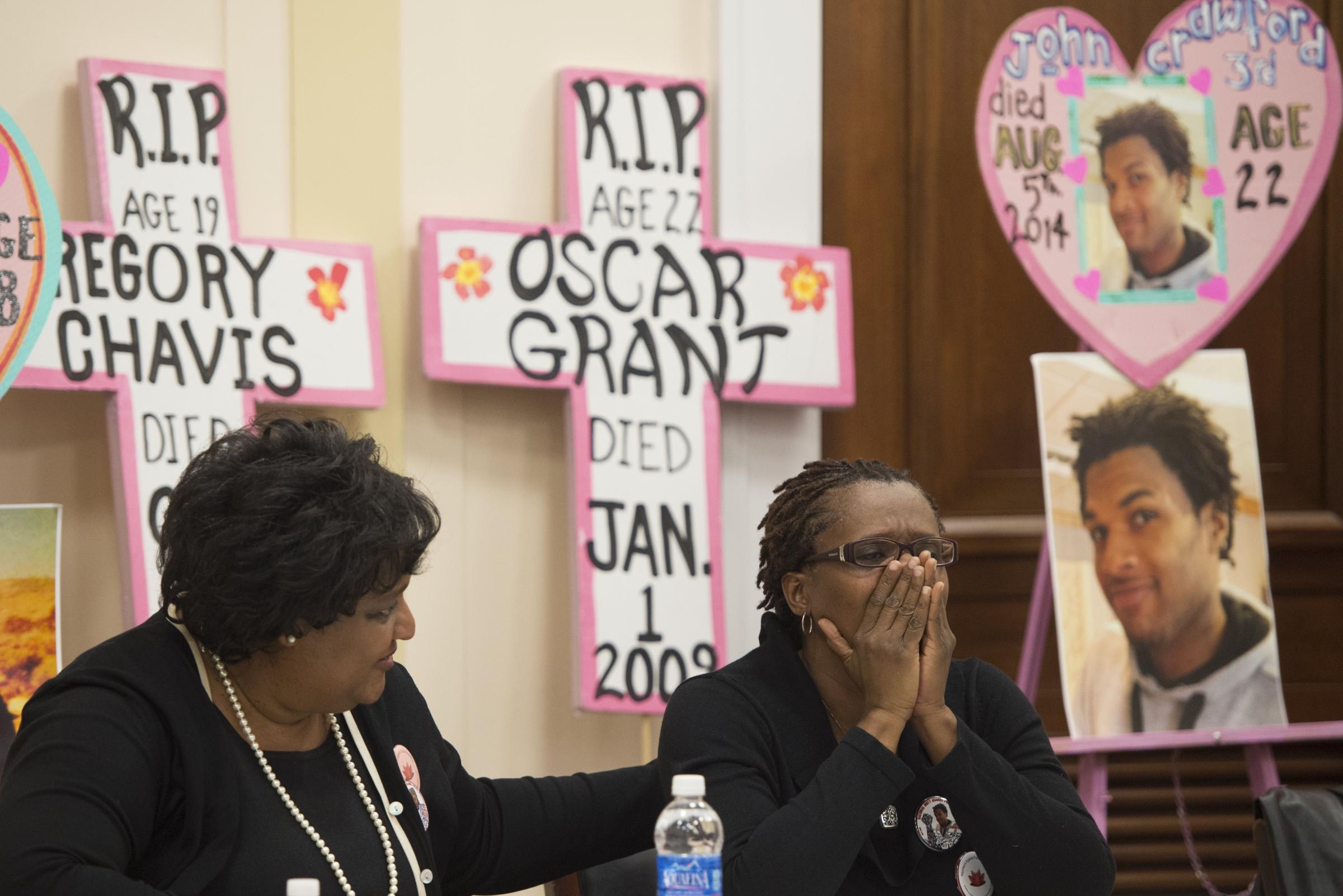

John Crawford III

Aug. 5, 2014 John Crawford III, 22, is shot inside a Walmart in Beavercreek, Ohio, after picking up an air rifle from the shelf. While police say they repeatedly asked Crawford, who was black, to drop the gun, surveillance video shows that police shot the man soon after approaching him.

Michael Brown

Aug. 9, 2014 Darren Wilson, a white Ferguson, Mo., police officer, fatally shoots unarmed 18-yearold Michael Brown, setting off months of unrest in the St. Louis area. Protests erupted nationwide in November, when Wilson was not indicted in Brown’s death. But the shooting prompted a Justice Department investigation of the Ferguson Police Department. In March, after the scathing report found instances of overt racism among officers and a pattern of arrests targeting black residents, Ferguson’s police chief and city manager resigned.

Levar Jones

Sept. 4, 2014 Levar Jones, 35, is shot multiple times by 31-year-old Sean Groubert, a white South Carolina state trooper, seconds after being stopped for a seat-belt violation, all of which was caught on the officer’s dash cam. Jones, who was black and unarmed, survived and can be heard on a video asking, “Why did you shoot me?” Groubert was later fired and charged with assault and battery, which carries a sentence of 20 years in prison. A verdict is expected later this year.

Tamir Rice

Nov. 22, 2014 Tamir Rice, 12, is fatally shot and killed in a Cleveland park after police responded to a 911 call reporting a person with a gun. The caller warned that the gun may have been fake, but the officers say they didn’t know that. Officer Timothy Loehmann shot Rice within seconds of arriving on the scene. Rice’s gun turned out to have been a toy. A group of political and religious leaders have called for criminal charges to be brought against the officers involved, and a grand jury plans to hear evidence in the case.

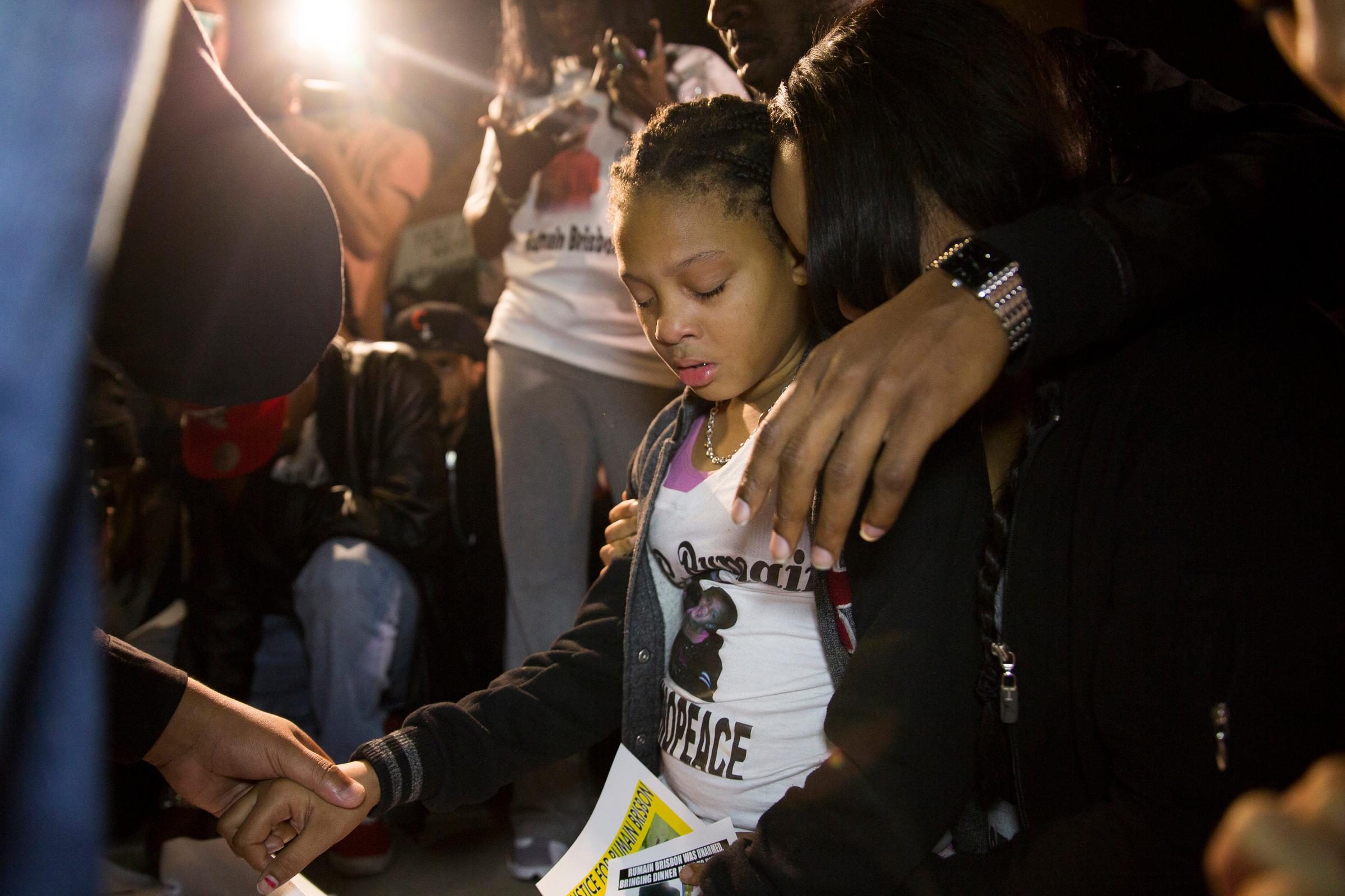

Rumain Brisbon

Dec. 2, 2014 Rumain Brisbon, 34, is shot and killed by a Phoenix police officer following a drug-related traffic stop in which Brisbon, who was black, fled, refused arrest and appeared to be reaching for a weapon. Brisbon was shot by Mark Rine, a 30-year-old white officer. The incident set off several demonstrations in downtown Phoenix. On April 1, a Maricopa County attorney announced that criminal charges would not be brought against Rine.

Charly “Africa” Leundeu Keunang

March 1, 2015 Los Angeles police officers shoot and kill a black homeless man named Charly “Africa” Leundeu Keunang, following a confrontation in the city’s Skid Row, an area with a heavy concentration of homeless people. Officers said the man attempted to take one of their guns.

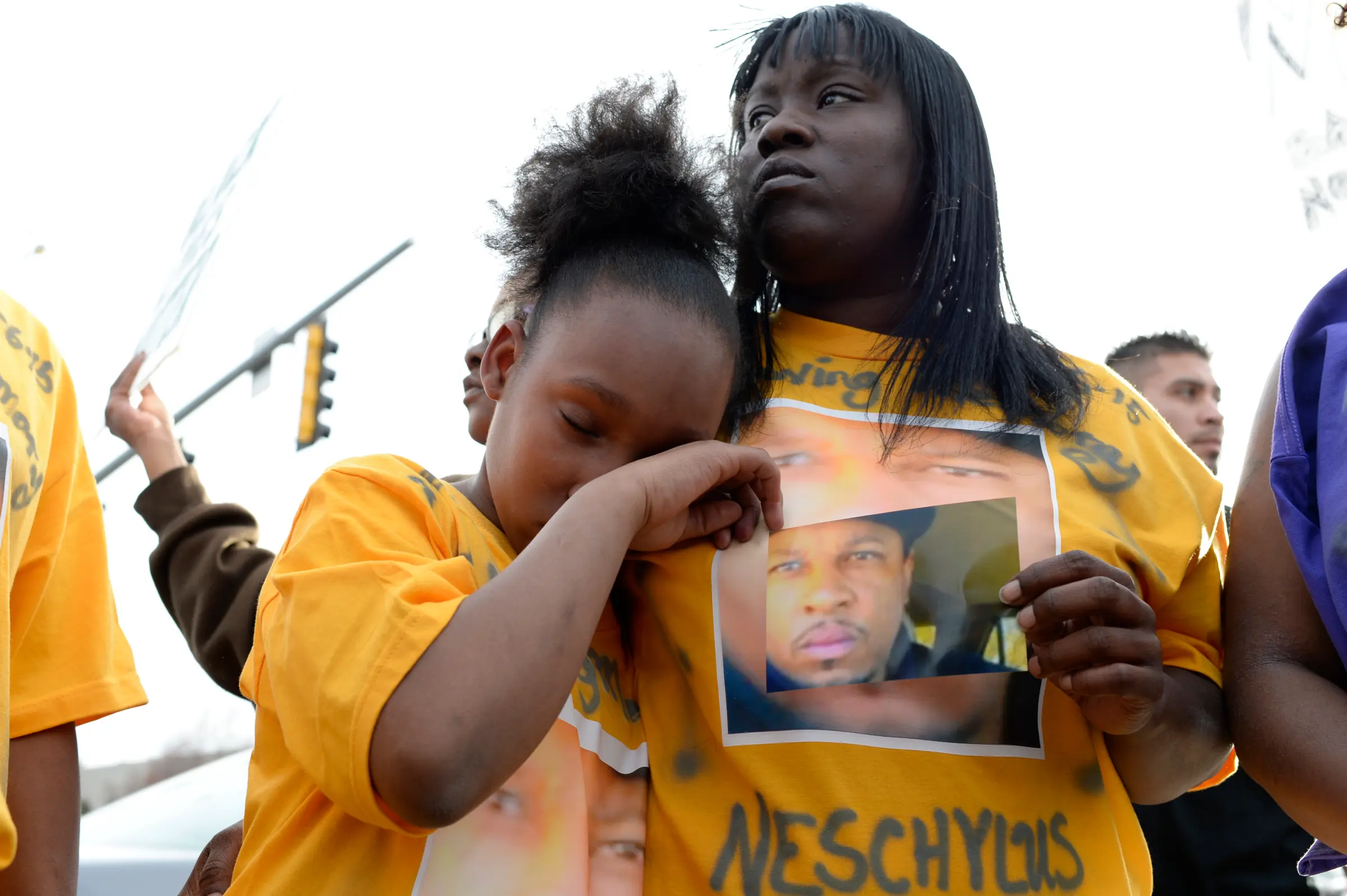

Naeschylus Vinzant

March 6, 2015 Naeschylus Vinzant, a 37-yearold unarmed black man, is shot in the chest and killed by Paul Jerothe, a police officer in Aurora, Colo. At the time of the shooting, Vinzant was violating his parole and had removed his ankle bracelet. He also had a violent criminal history but was unarmed as officers tried to arrest him. Jerothe, a SWAT team medic officer, has been placed on administrative leave pending an investigation.

Tony Robinson

March 6, 2015 Tony Robinson, a 19-year-old biracial man, is shot by a white Madison, Wis., police officer after Robinson was allegedly jumping in and out of traffic. Matt Kenny, a 45-year-old officer who was exonerated in a 2007 shooting of an African-American man, got into an altercation with Robinson when he entered an apartment in which Robinson was reportedly acting aggressively. Kenny, who says he was attacked by Robinson, was placed on administrative leave with pay pending the results of an investigation.

Anthony Hill

March 9, 2015 Anthony Hill, a black 27-yearold Air Force veteran, is shot and killed in Chamblee, Ga., by Robert Olsen, a white DeKalb County Police Department officer. Hill was naked and unarmed at the time of the incident and was apparently knocking on multiple apartment doors inside a housing complex. Olsen has been placed on leave. An investigation by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation is currently under way.

Walter Scott

April 4, 2015 Walter Scott, a 50-year-old black man, is shot and killed as he’s apparently fleeing North Charleston officer Michael Slager, 33. Slager, who is white, alleges that Scott reached for his Taser. A video recorded by a bystander appears to show Scott running away from the officer as he’s shot in the back eight times.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com