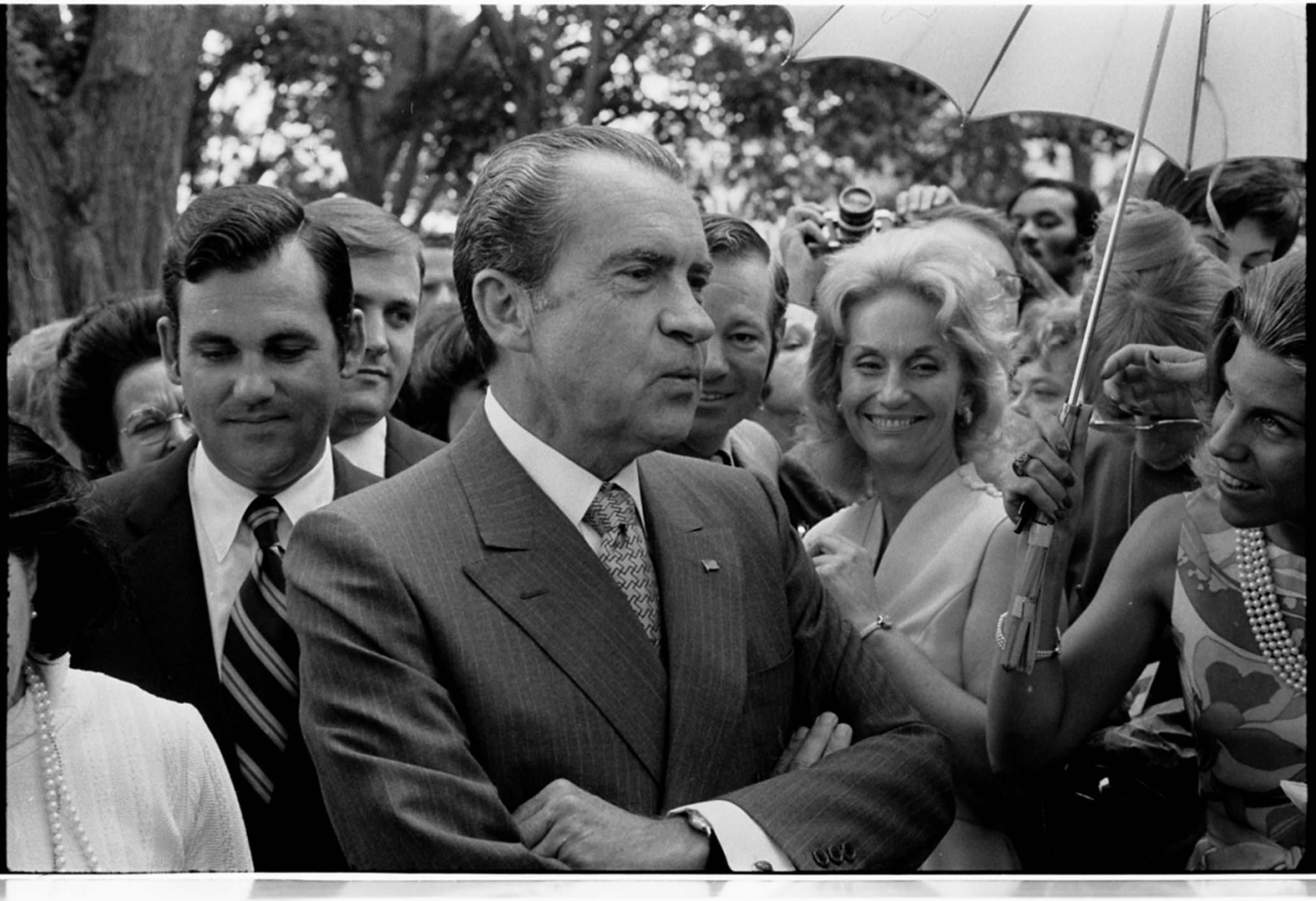

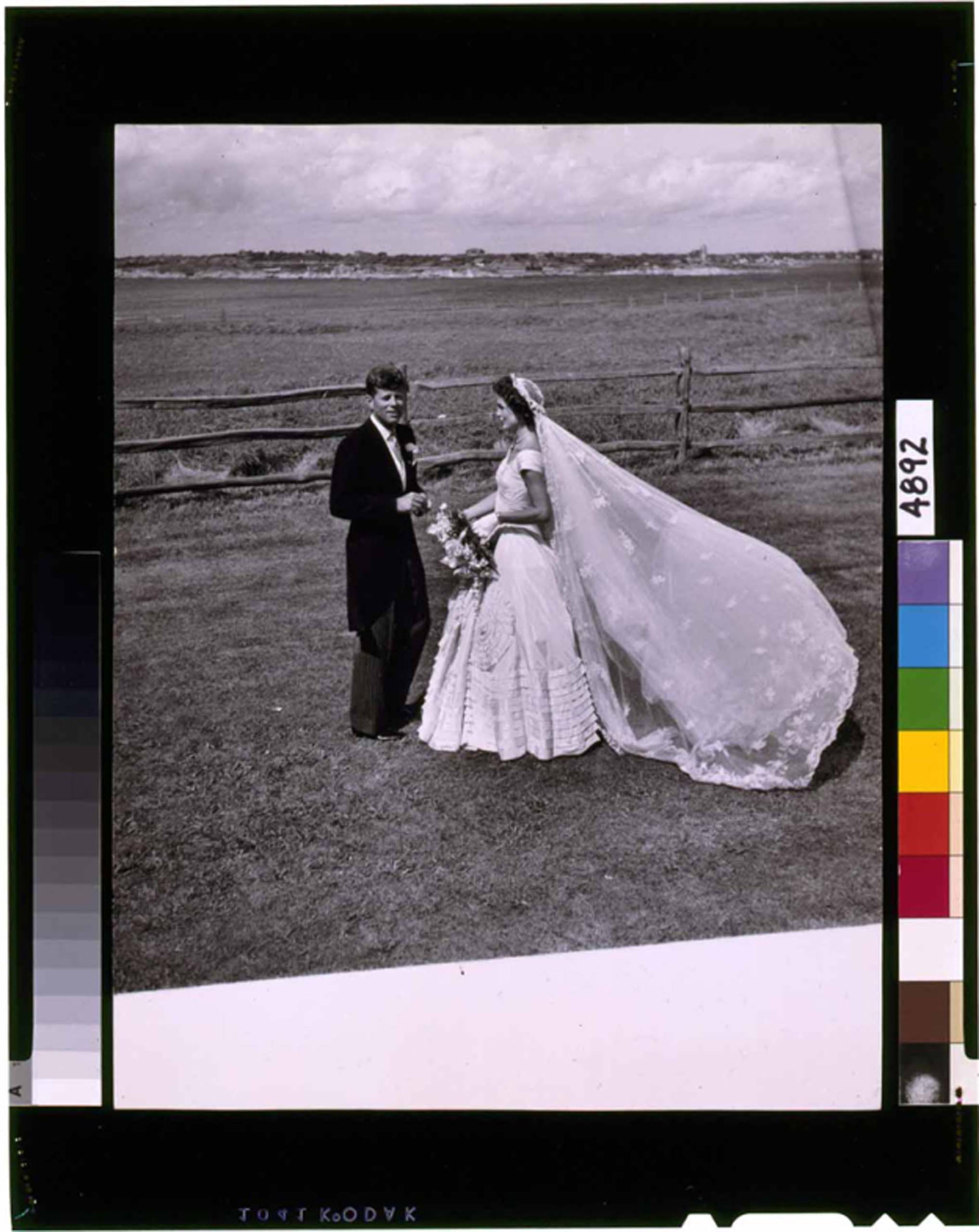

In a recent New York Times interview with Thomas Friedman, President Obama enunciated an “Obama doctrine” for dealing with nations such as Cuba and Iran: “We will engage, but we preserve all our capabilities.” By “engage,” he meant engage diplomatically; by “capabilities,” he meant our overwhelmingly superior military. Following the example of President James Monroe, a great many modern Presidents have enunciated explicit or implicit doctrines, including Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, Carter, Reagan and George W. Bush. Some of them pushed the United States further forward in the world; others represented something of a step back. Putting Obama’s doctrine in historical perspective suggests that he is returning to an earlier tradition of American foreign policy represented above all by those two great rivals, Kennedy and Nixon—but, typically, Obama used vaguer, gentler language than any other President, continuing his endless, so far fruitless search for consensus.

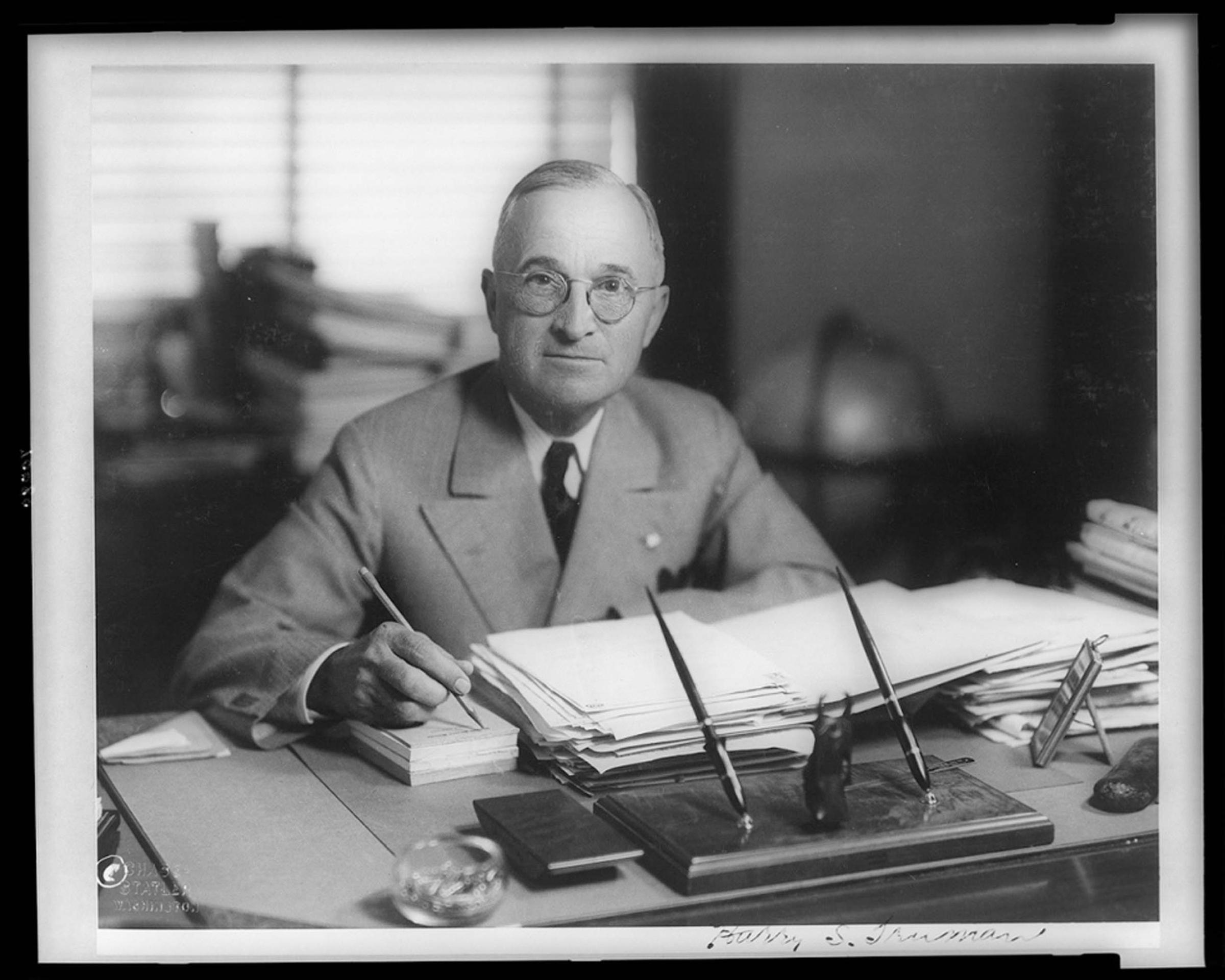

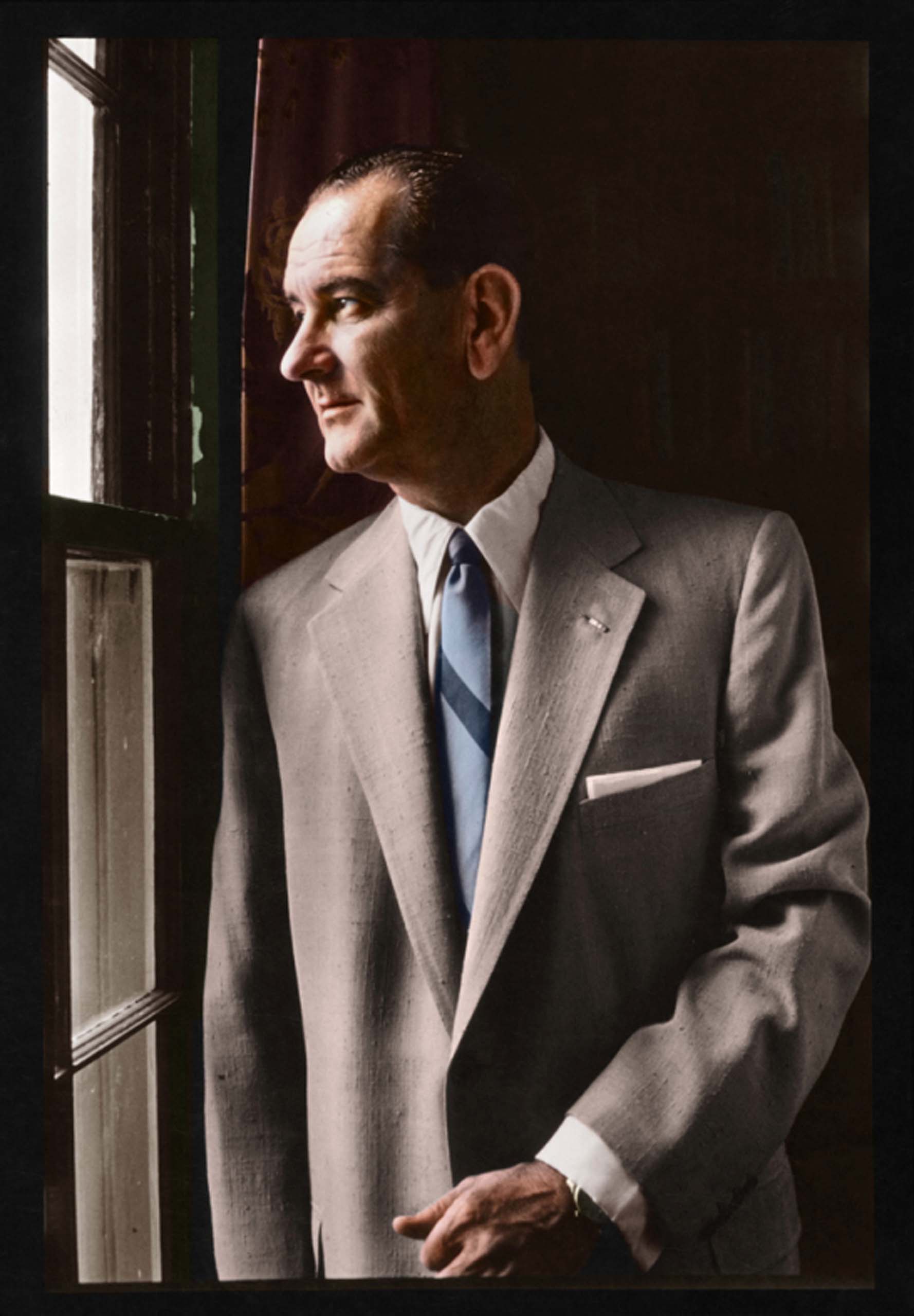

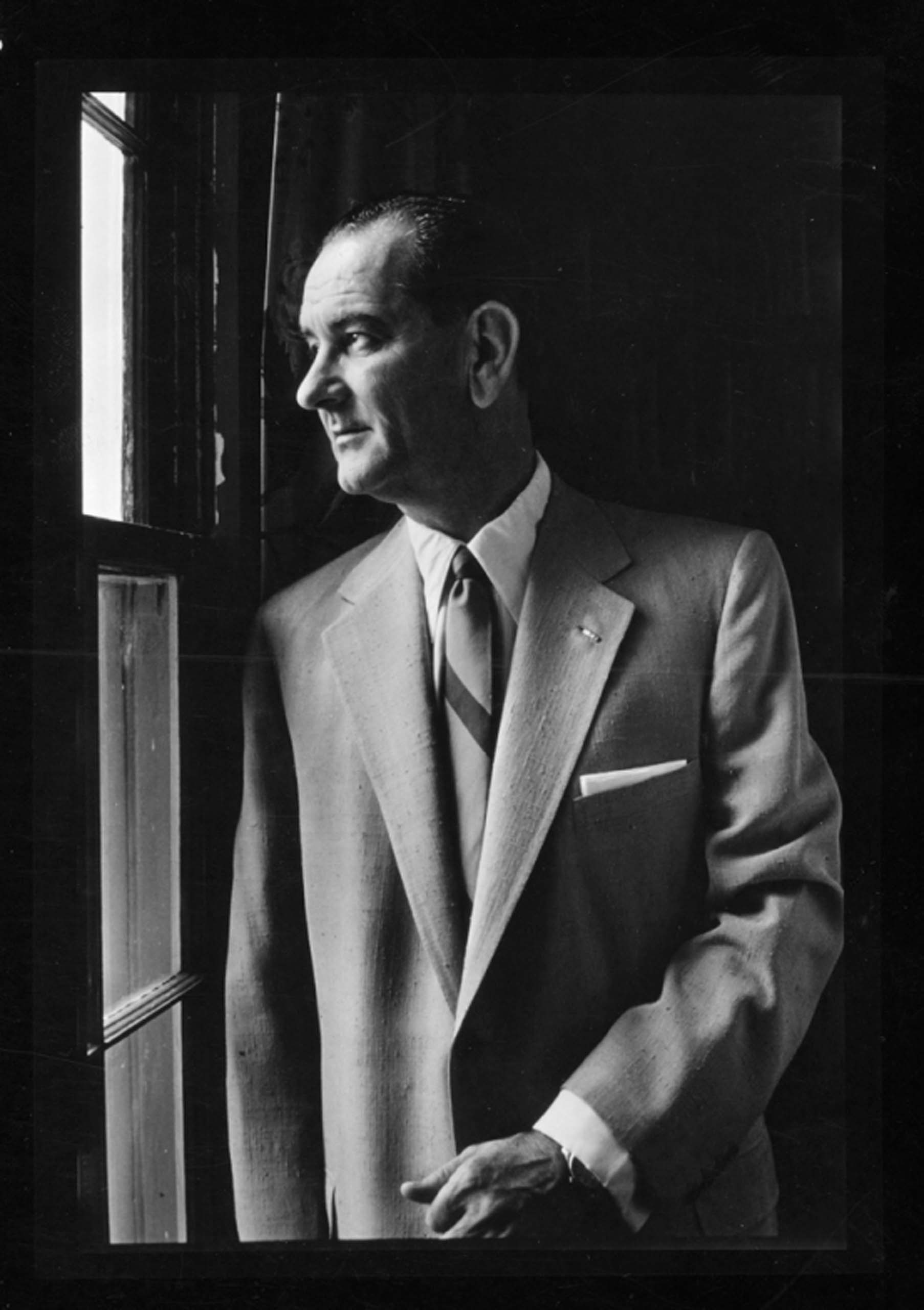

The Truman Doctrine, presented to Congress and the world in a March 1947 speech, set the tone for the next 40 years of American foreign policy. Confronted with a civil war in Greece, President Truman argued that the United States should give aid to allied governments that were resisting internal rebellions aided by outside forces. While he did not specifically identify Moscow as the ultimate enemy, the speech became the basis for the containment strategy that ruled our foreign policy until 1989. And in fact, the Eisenhower, Nixon, Carter and Reagan doctrines were all simply extensions or modifications of containment. Eisenhower in 1957 announced that the United States would resist Communist encroachment in the Middle East. Nixon in 1969 stated that the United States would no longer send ground forces to help third-world allies threatened by Communist aggression, but would use naval and air power. Carter in 1980 announced that the United States would forcibly resist any Soviet attempt to move into the Persian Gulf region. Going a step beyond containment to liberation, Reagan in the 1980s declared that the United States would assist guerrillas fighting Communist regimes in the Third World.

More broadly, however, different Presidents enunciated different principles behind the ends and means of their foreign policy, particularly towards the Soviet Union. Thus, in his American University speech in June 1963, John F. Kennedy called for peaceful coexistence between the United States and the Soviet Union, founded on mutual respect for one another’s institutions and even beliefs. The Test Ban treaty followed in short order. Nixon not only enunciated his own doctrine, but declared, echoing Kennedy, that there could be no winners in a nuclear war, and embarked upon détente with the Soviet Union and arms-control treaties based upon equality. Reagan on the other hand declared, through subordinates, that the United States must prepare to fight and “prevail” in a nuclear war with the Soviets, whom he often argued, until the advent of Mikhail Gorbachev, could not be trusted.

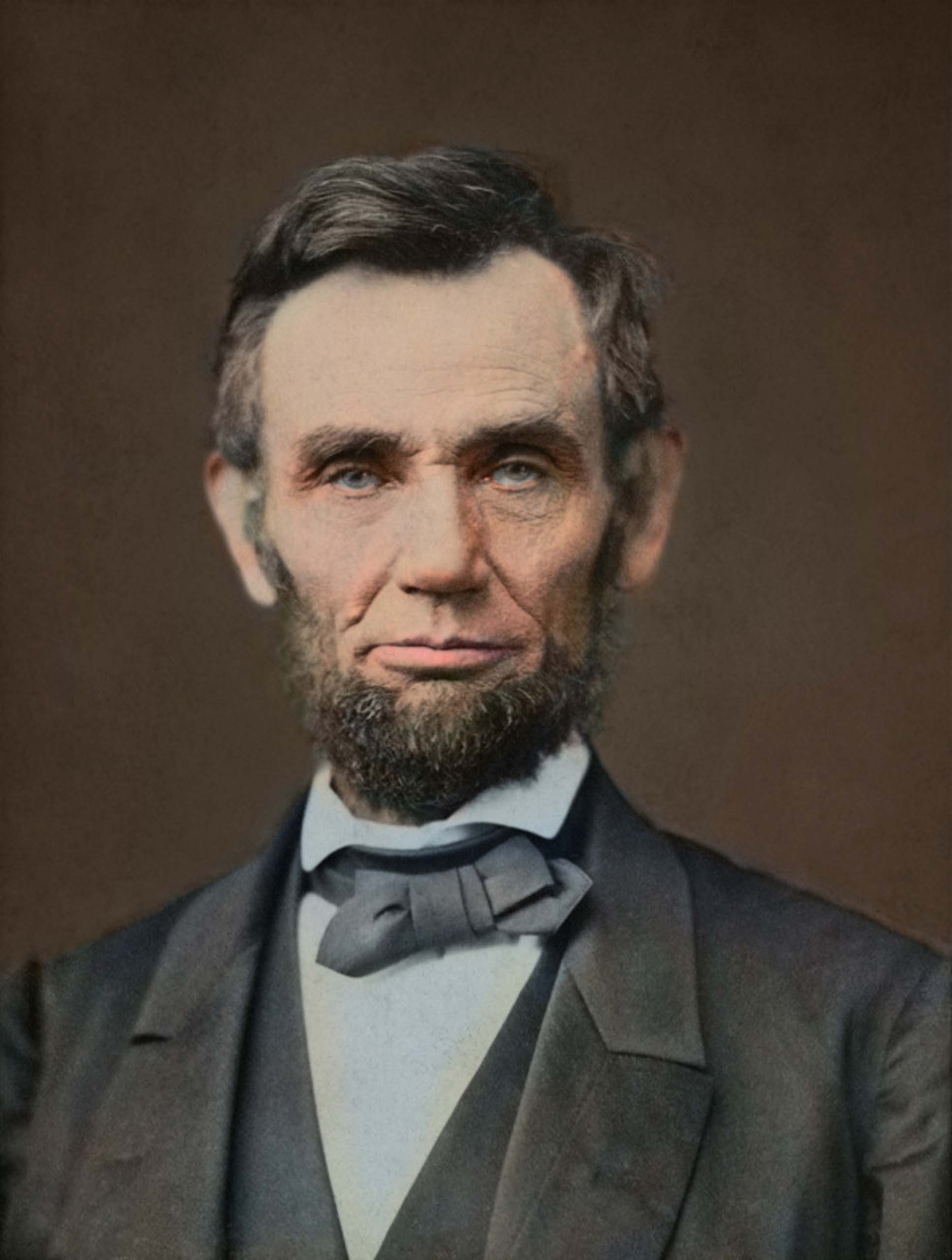

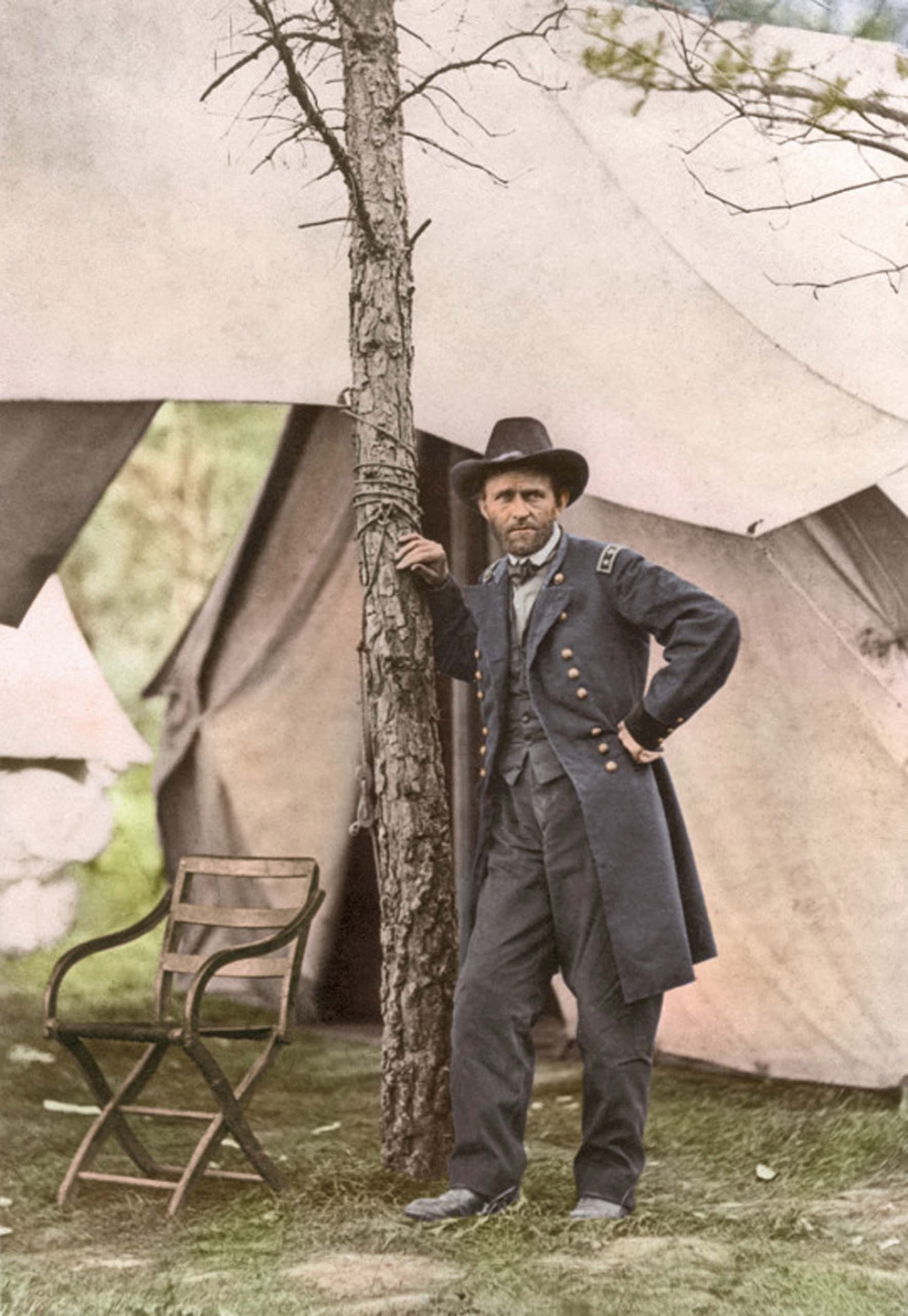

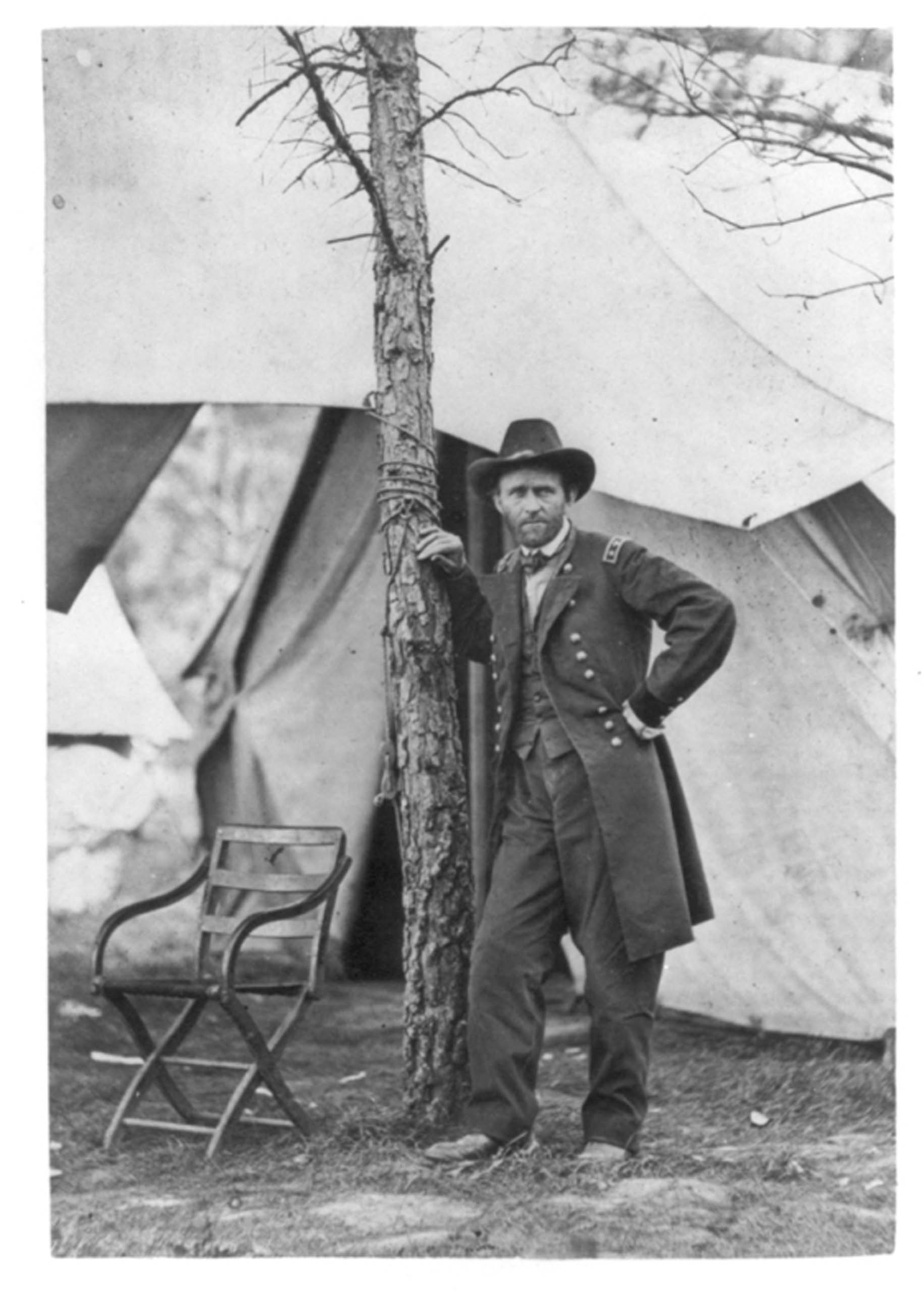

Bringing Color to Presidents Past

![presidents-past (14) Abraham Lincoln, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing front. Date Created/Published: [photograph taken 1863 Nov. 8; printed later and c1900]. Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/presidents-past-14.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

The collapse of Communism and the end of the Cold War in 1991 opened up new vistas for foreign policy. George H. W. Bush essentially unveiled a new approach to aggression in response to Saddam Hussein’s occupation of Kuwait, using the United Nations to form an overwhelming coalition to roll back Saddam’s aggression without trying to overthrow him. (It is interesting that neither Kennedy nor Bush the elder, whom I consider the two most effective diplomats to have occupied the White House in my lifetime, saw fit to enunciate a “doctrine” that might serve as a substitute for case-by-case analysis.) In 1999 Bill Clinton went a fateful step further, undertaking the Kosovo war without the full support of the U.N. Security Council, and establishing a precedent that Vladimir Putin loves to invoke. But the real shift came in 2002, when George W. Bush’s administration, in a new National Security strategy, announced that the United States would use its overwhelming military power to prevent dangerous or hostile states from acquiring weapons of mass destruction, without regard to the rest of world opinion. This doctrine led us into Iraq, and had Iraq gone more smoothly, it might well have led us into Iran and North Korea as well.

The Obama doctrine seems to represent an explicit, although vaguely stated, return to a policy of containment and deterrence, in the tradition of Kennedy and Nixon. It repudiates not only preventive war, but also the fantasy that economic sanctions can bring down or fundamentally alter hostile regimes. Our sanctions against Castro have lasted the whole of Barack Obama’s natural life, without result. While the agreement with Iran may not work out as planned, Obama said, “Iran understands that they cannot fight us.” That argument—that Iran can be, and is being, effectively deterred from war by American power—trumps, in the President’s mind, Iran’s ideological stance, and especially its rejection of Israel’s right to exist. The President rejected Prime Minister Netanyahu’s demand that Iran be required to accept Israel’s existence as part of the deal. In the same way, Nixon and Kennedy (although not Reagan) made important agreements with Soviet leaders without trying to insist that they renounce their ideology.

Iran has in fact made remarkable concessions for the sake of the agreement. Because successive Presidents have declared that Iran must not have a nuclear weapon, we tend to forget that nothing in international law forbids them from enriching uranium, and only the Nonproliferation Treaty, which the Iranian government signed but could denounce, as North Korea did, forbids them from developing weapons. The Iranian government, a proud and militant regime, is surrendering a good deal of its sovereignty for the sake of improving its economy and its relations with the West.

The President is moving towards a new, more realistic approach to the Arab world, one that does not demand a wholesale capitulation to American policies and values as the price of any cooperation with the United States. Given the intense opposition that he faces at home, however, I do not know if he can bring this shift about without using less tentative and more inspiring language than he did in his interview with Friedman. Both Kennedy and Nixon, following parallel courses in their dealings with Moscow, spoke boldly of a new era of peace and a potential end to a nuclear nightmare. Today’s President remains “No drama Obama.” The shift he is proposing is truly dramatic, especially against the background of the last 15 years, but it may need more inspiring rhetoric to turn his vision into reality—lest his opponents’ jeremiads against the dangers of the agreement drown out his very sensible arguments for it.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com