There are two narratives of how Dina, a gang member in the northern village of Matsaborilava, Madagascar, died last August. Police suspected the 33-year-old was partly responsible for the death of a cocoa plantation’s security guard earlier in the year. When they went to his house, officers claimed he lunged at them with a machete and that they shot him dead in self-defense. Dina’s wife, the mother of his two children, tells it differently: After officers barged into their home at night and asked three times “Are you Dina?,” to which he replied yes, they handcuffed him and then shot him twice in the head.

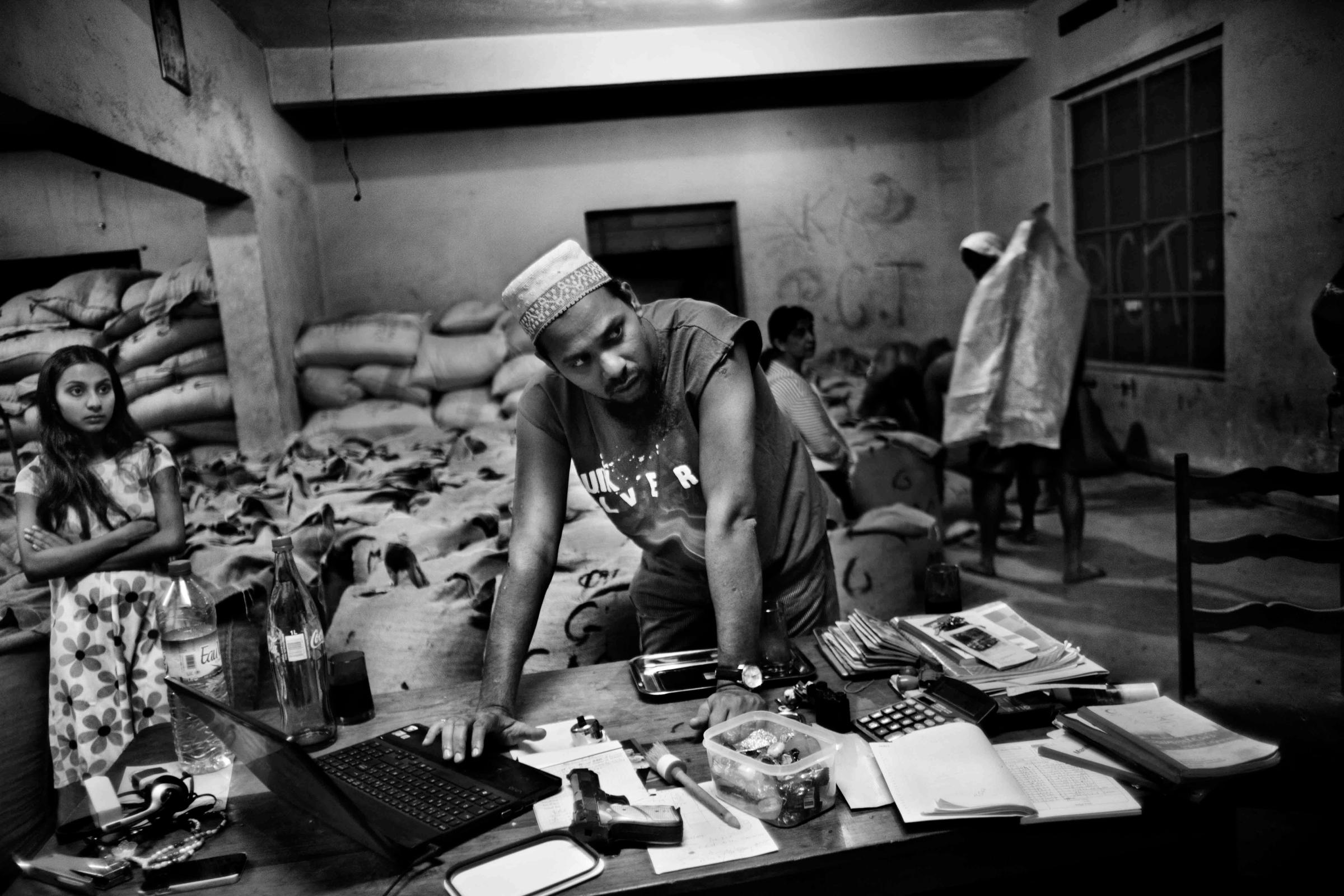

Giulio Di Sturco, an Italian photojournalist based in Bangkok and New Delhi, arrived the next day, five months after his first assignment documenting the cocoa battle between farmers and gangs. Dina’s death marked the first in the local police’s new operation against the bandits. Having kept in touch with an official in northern Ambanja through his fixer, Di Sturco arranged a three-week trip to see it all: the plantations on which farmers earn their living and from which gangs steal; the ill-equipped police; the middlemen who actually turn a profit; and the families who never asked to be involved in the mayhem.

Cacao trees in the remote Sambirano Valley yield some of the world’s finest cocoa pods, a favorite among chocolatiers in the West, and should be a boon for farmers. But a coup five years ago prompted a repeal of external funding, which had accounted for 40 percent of the state’s budget, pushing poverty higher and causing investments to dry up. For a country where some 92 percent of its 22 million people live on less than $2 per day, making it one of the poorest in the world, cocoa banditry can be an attractive option.

Gangs in the north steal beans from farms or hijack shipments on the roads, keeping laborers poor. Many large farms make enough money to employ security teams, Di Sturco says, but smaller ones must defend themselves. “From 3 o’clock in the morning until the sun is high, they patrol their small plantations with machetes and javelins, and the gang comes in with homemade guns,” he adds. “It’s a small medieval war.”

Di Sturco spent most days with the farmers and nights with the police. His honesty with the gangs resulted in access he had only dreamed of during his first trip. “They said, ‘We’ll speak with you, we’ll let you take pictures,'” he recalls, “but they said, ‘we trust you not to go with the police.'” In response, Di Sturco told the gang members that if they killed somebody, he was going to take pictures of the funeral. “And they were kind of okay with that.”

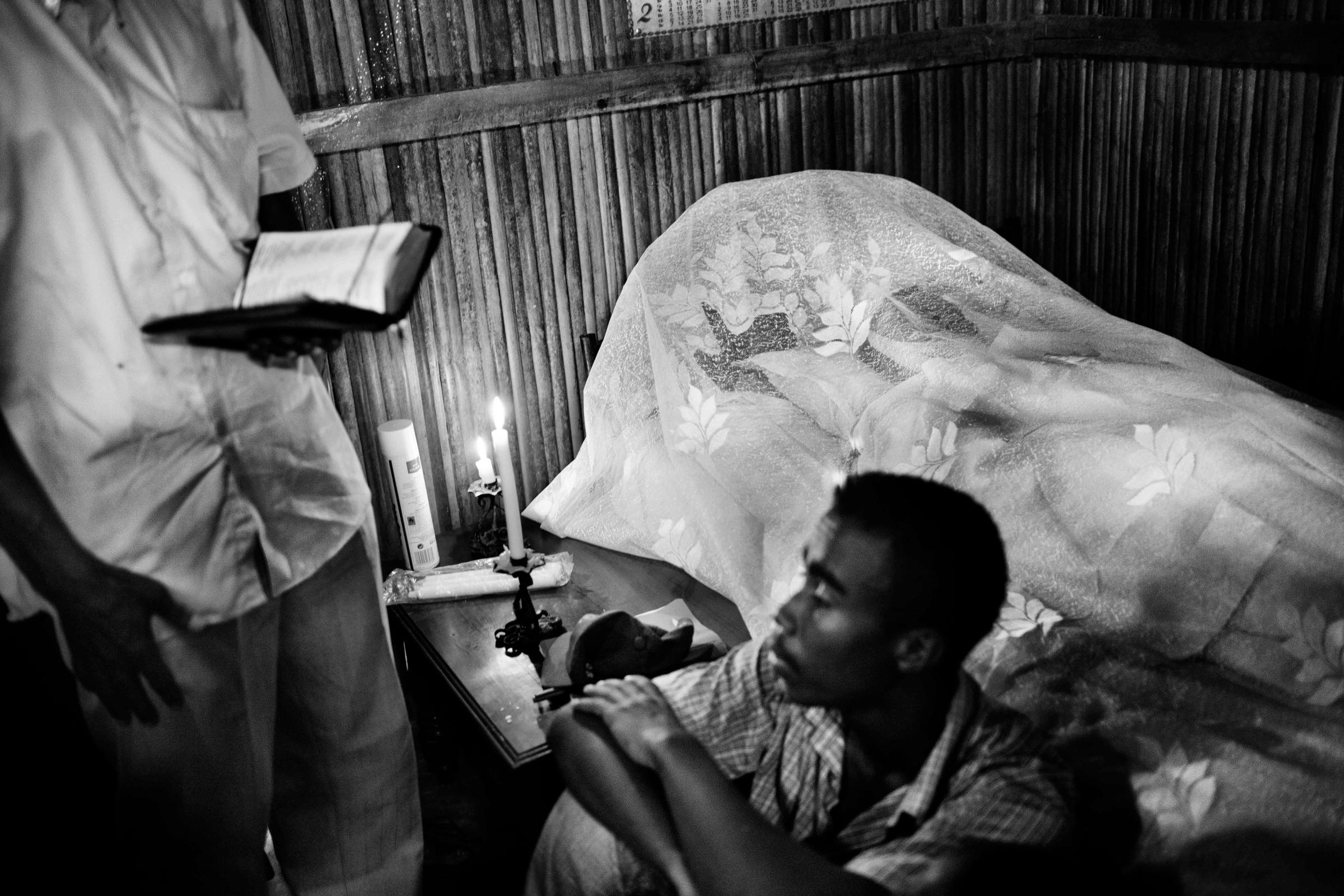

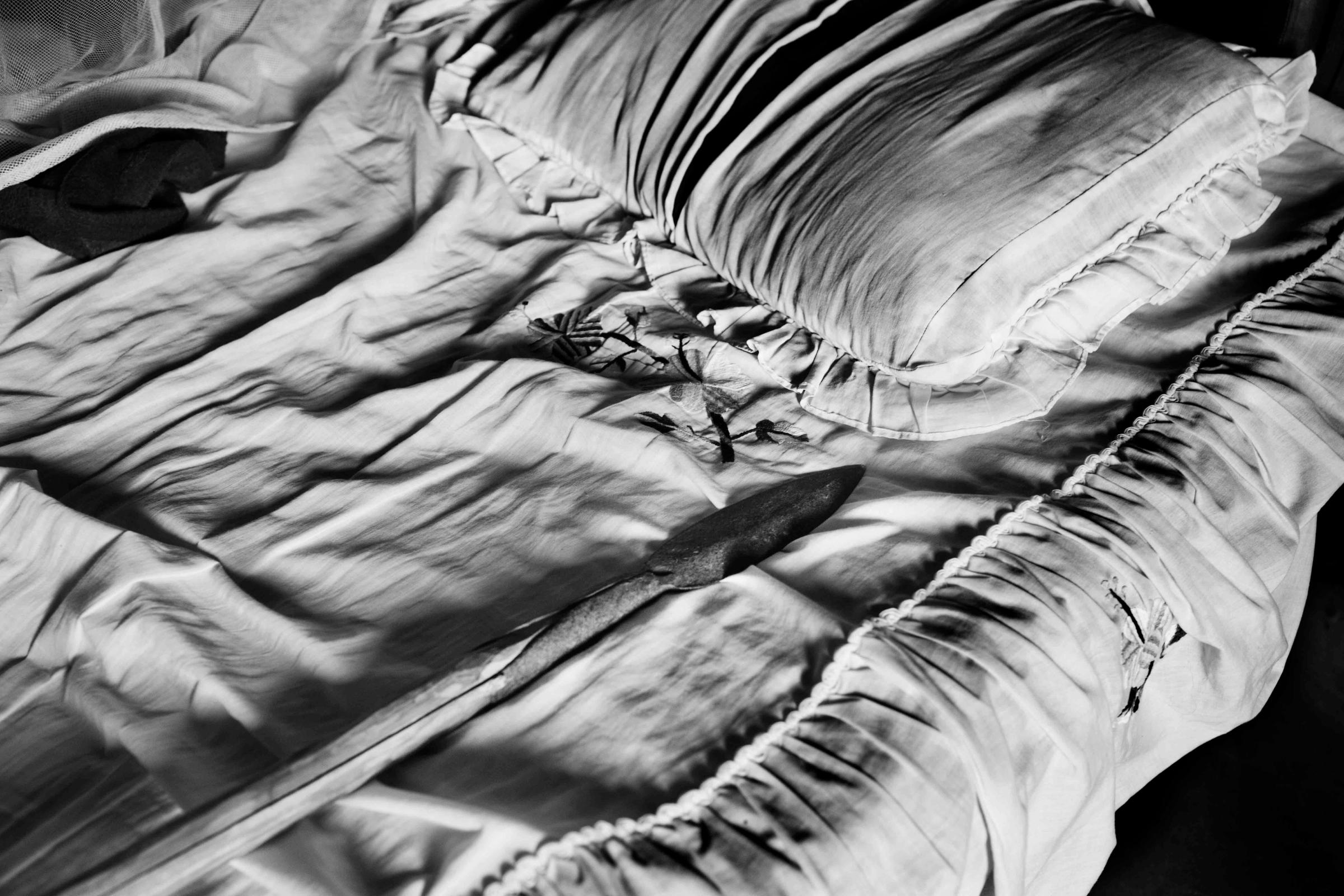

Before he could photograph Dina’s funeral, he had to wait in his hotel for access. The formal tradition is that a member of the deceased’s family comes to talk, over a pot of tea, and then makes a decision. Once Di Sturco told the family how police recalled Dina’s death, a version that differed from theirs, they agreed to let him document the funeral. Dina’s coffin was paraded around Matsaborilava so everyone could see he was killed by the police, but Di Sturco says they weren’t told why. Two policemen showed up, one of them the commissioner, whose apology to the mother of Dina’s wife was viewed as sincere.

Di Sturco is finishing a long project in India and Bangladesh about the Ganges River but says he will return to Madagascar if there’s a big development in this story. He plans later this year to photograph at a chocolate fair in Paris, where there will be many beans from Madagascar. Those images will give him the whole project, from bean to bar and everything in between. Di Sturco admits this work isn’t about getting people to change their opinions or habits: People won’t stop eating chocolate just because others are killing each other over it. Rather, it’s about informing them about the consequences of their cravings.

“Everybody knows that cocoa in Madagascar is good,” he says, “but nobody knows the war.”

Giulio Di Sturco is a photographer with Reportage by Getty Images. His work has appeared in TIME, Geo magazine, Vanity Fair, The Daily Telegraph, The Sunday Times Magazine and many others.

Andrew Katz is a homepage editor at TIME and reporter covering international affairs. Follow him on Twitter @katz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com