His photos have been prized on the international art market for years and adorn the walls of leading photo galleries across the world, but 76-year-old Malick Sidibe still resides in a one-room home in Mali so timeless that it feels as if the air within hasn’t stirred in decades. Marked boxes — 1972, 1968, 1965 — containing much of Malick’s vast archive balance atop one another, stretching to the ceiling. Orphaned 6 x 6 frames dot the floor. A large wooden crate bulges with ruined cameras in a tangled mass. Occasionally the scorching air outside shifts, sending a breeze through the room that does nothing to dispel the overwhelming heat inside. On a good day, electricity powers a single bulb that barely illuminates the otherwise pitch-dark space. Decades’ worth of Malian dust covers every surface.

Malick is not surrounded by the material trappings one might expect a major contributor to the contemporary arts landscape to enjoy, or pursue, nor do I imagine he spends much time obsessing over his place in the photographic firmament. In this way he is, to my mind, the perfect artist. His wives and children constantly attend to him, and while inside his home time seems not merely to slow but to cease altogether, the courtyard outside buzzes with activity. A national hero, his contribution to his country’s historical record has, for many, crafted the image of Mali.

In his home, light years from the art centers of the world, Malick is, I trust, exactly where he wants to be in his life and in his career — the same neighbor to Malians that he has always been, despite the fame that has gradually found him.

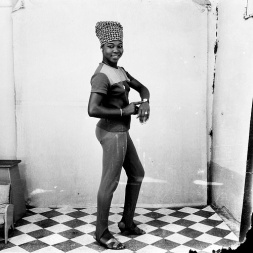

Housed in a busy suburb of Bamako, Mali’s capital, Malick’s tiny studio has a readily detectable pulse — a touch shallower than I imagine it once was, but still present. The studio itself has become as much a subject in his photos as the countless men, women and children who have set foot inside the place to have their portraits made, or simply to visit with the local legend. The portraits, meanwhile, are remarkable, each one of the thousands of pictures somehow teasing out a central, telling element of the individual’s character. These portraits, one realizes, are evidence of a rare and intimate exchange, an empathy between sitter and portraitist.

Digging through Malick’s archive I continually encountered series after series of photos that he had started and never finished, pictures that were unlike anything else I had seen from him. His challenges to the methodology of traditional studio portraits were clearly evident in these projects, and my admiration for his work — and for him as an artist and as a man — brought me back to his home every single day while I was in Bamako. All my questions about his techniques and his philosophy of photography having run their course, I was content at last to simply visit and sit with him, time and again. I suspect he makes everyone feel as welcome as I felt.

As a photographer, being around Malick in his small, storied, marvelous studio stirred something in me. The unflinching commitment to his ever-evolving, self-realized process, and his evident contentment with the place he has carved out for himself in the world of art, is both humbling and inspiring; his example forces me to engage the personal fears and hesitancies I suffer in my own work. The perfect artist, it seems to me now, fully gives himself over to a hard-earned trust in his own work, in his own methods. He doesn’t just avoid the creative roadblocks that so many of us place in our own paths; instead, he is so quietly confident making his own way that the roadblocks simply don’t exist.

Malick Sidibe is a Malian photographer. He is represented by Jack Shainman Gallery in New York, Afronova Gallery in Johannesburg and Fifty One Fine Art Photography in Antwerp.

Jehad Nga is a New York-based photographer. LightBox has previously featured Nga’s Green Book Project as well as work about his Libyan roots and a photo essay on the world’s biggest refugee complex.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com