“I had a good time in Iraq, but that last tour was a real blast. It took me four tours to realize my lucky number is 3.”

—Bobby Henline

This essay is one part of our feature on Bobby Henline. See Red Border Films’ full documentary on his story at TIME.com/RedBorder

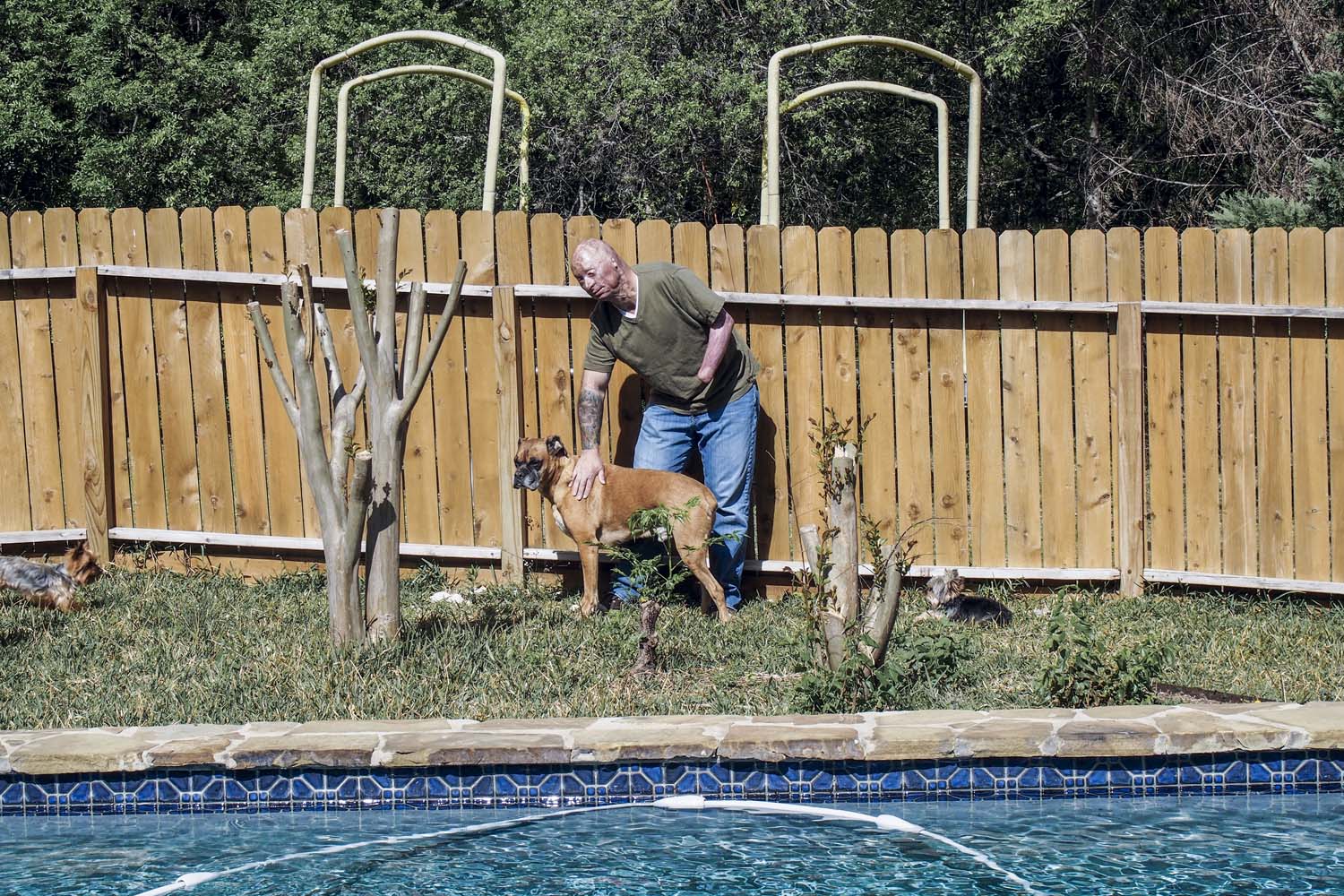

On April 7, 2007, three weeks after Bobby Henline arrived in Iraq for his fourth tour, his humvee was blown up. The four soldiers with him were killed. Henline was the sole survivor of the blast from the improvised explosive device, but he was only so much luckier: bones in his face fractured, burns covered close to 40% of his body, and his left hand later had to be amputated. He spent two weeks in a coma.

The early months of recovery were a blur. He put nurses in headlocks and sang, over and over again, “How much wood could a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood?”

Returning home was even harder. Henline, now 42, and his wife of 20 years have three kids. Between his time in Iraq and his six months in the hospital, they had become used to his absence. “They’ve changed, you’ve changed,” Henline says.

At home, Henline realized the extent of his injuries. He didn’t want to be a burden on his family. And every day, he was haunted by the lingering memories of war.

“You have to live with a different mind-set there that you can’t live with here,” he says. “You need to let it go, but it’s so hard to turn off. PTSD takes you back to that place. When you get home, the kids want to jump on you, climb on you, and you feel like, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.”

Henline prayed for God to take him in his sleep.“You get used to getting stared at and looking at yourself in the mirror. It becomes you. But there are days I don’t want to be stared at . . . Still, I feel sexy. Once you’re cooked, you’re hooked.”

While he was rehabilitating with other wounded soldiers, Henline tried to keep their spirits up by telling them jokes. His therapist kept nagging him to get into stand-up comedy, and in 2009 he finally relented, trying his hand at an open-mike night. It was a flop, but Henline loved it.

Finally, here was a space where he could acknowledge the first thing people notice when they see him, where he didn’t have to avoid talking about the experience that changed his life. So he kept telling jokes.

“On the Fourth of July I always go to a fireworks stand. I run up real excited and ask them, ‘Can you give me the same stuff as last year? It was great!’ ”

Another favorite: “In about 10 years I can go to my roast precooked.”

Henline started providing comic relief for other burn survivors, greeting new patients at the Brooke Army Medical Center near San Antonio and regularly visiting a 12-year-old who had been burned as a toddler and had undergone dozens of horribly painful skin-graft surgeries. An atheist before the explosion, Henline has come to believe in some sort of higher power. Faith — in a common energy rather than a specific religion — sustained him through his long and difficult recovery. And he credits a vision he had while in the coma with steering him toward comedy. “I was on a giant iceberg at night,” he recalls. “The stars were out. It was comfortable. I heard voices telling me it was going to be O.K. I thought I was in the judgment room, and it was God telling me I was going to go back — that I had a mission, but it would be on his terms.”

Watch as Henline narrates personal photographs from before and after his deployment:

“The skin on my scalp burned off, so the doctors replaced it with my stomach. When I eat too much I get headaches.”

Every comedian is trying to get a laugh, and Henline is no different. But he has a second aim, one that can offer an extra layer of meaning this Veterans Day. More than 51,000 troops were wounded in action during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Department of Defense reports. And not every scar is physical. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD, 11% to 20% of veterans of those conflicts have experienced post traumatic stress disorder.

“What I want to do,” Henline says, “is to help more people than the guy that blew me up can hurt.”

Peter van Agtmael is a conflict photographer and member of Magnum.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com