On the last page of Mark Steinmetz’s 2006 book South Central there is a small acknowledgment that reads ‘Dedicated to France and its great photographers.’ France, the birthplace of photography, and more importantly to Steinmetz, the country where his mother was born is also where the first image to record a human figure was made. In 1839 Louis Daguerre took a photograph of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris and, by chance, captured a man getting his shoe shined who stayed still long enough to be recorded within the ten-minute exposure. This is the start of what has become a very long and engaged tradition of photographing a city that has spanned the lives of many great photographers including the likes of Eugene Atget, Andre Kertesz, Brassai, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Mark Steinmetz’s newest book from Nazraeli Press called Paris In My Time, offers homage to the city of lights.

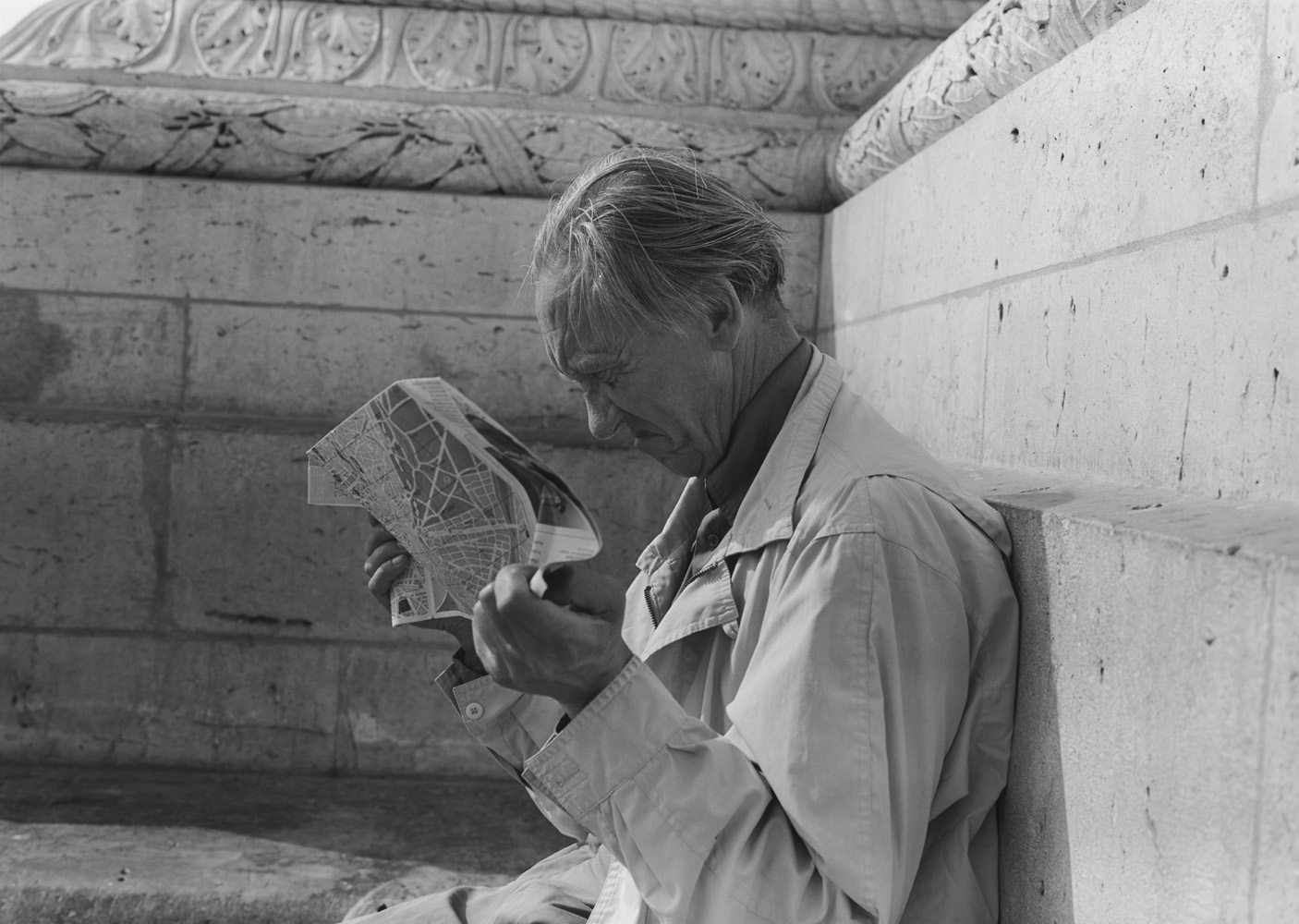

Known for intimately photographing his immediate surroundings in Georgia and the Southeast – the subject of a trilogy of books by Steinmetz – one might wonder if there are similarities between Paris and the Southeast. In Steinmetz’s photographs the rhythms of both seem quiet and in sync; slowness seems to pervade, but that may well be just a matter of photographic style. The opening photograph in Paris in My Time is of a man in a raincoat with suitcase – a visitor – lounges with the relaxed casualness of a child upon a wall taking in a hazy view of the Eiffel Tower. There is a nod towards romance to the image but the man’s clothes and slight absurdity of his posture derails that quick conclusion. The photographic tradition in Steinmetz’s hands is acknowledged and yet run through a different set of paces.

Made over the last 25 years, the photographs were taken on several extended stays in the city. “My mother was French (my father was Dutch) and I speak the language fairly well and love their photographic tradition so it made sense that I would introduce myself to Europe through France. The earliest of the photographs in the book were made in the mid-1980s when I was in my early twenties. I would sublet my apartment and go to Paris where I would stay with old friends of my mother’s. They would put me up and feed me so it was wonderful – I could go out and photograph all day.”

When asked if he sees the Paris work as just an extension of his work at home, “I do think the work in Paris is different from my work in America but perhaps not so fundamentally different. I loved the French photographers from the 20s and 30s and imagine I am stepping somewhat into that tradition. Many of the Paris pictures relate to photos I made a long time ago in public places such as Central Park in NYC or along the beach in California.”

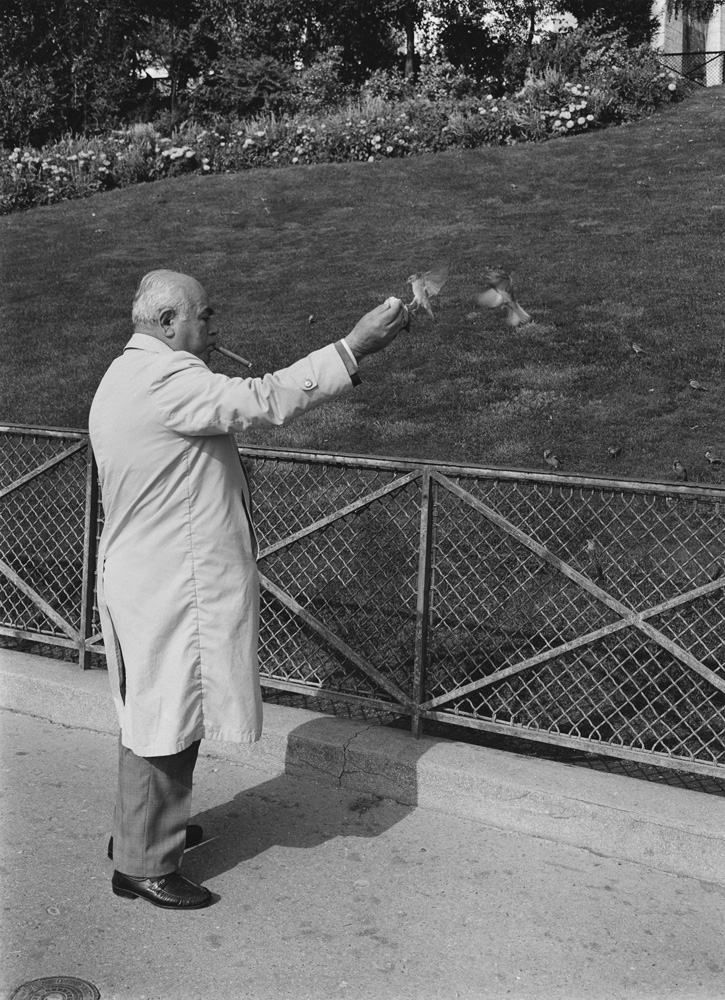

As Steinmetz acts the flâneur, most of the people he photographs also seem to be on their free time. No one is seen working and most are at play. Lovers lounge in the sun and children explore. The young boy with a fully rigged sailboat becomes a modern equivalent (or grandson!) of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s boy carrying two wine bottles from 1954.

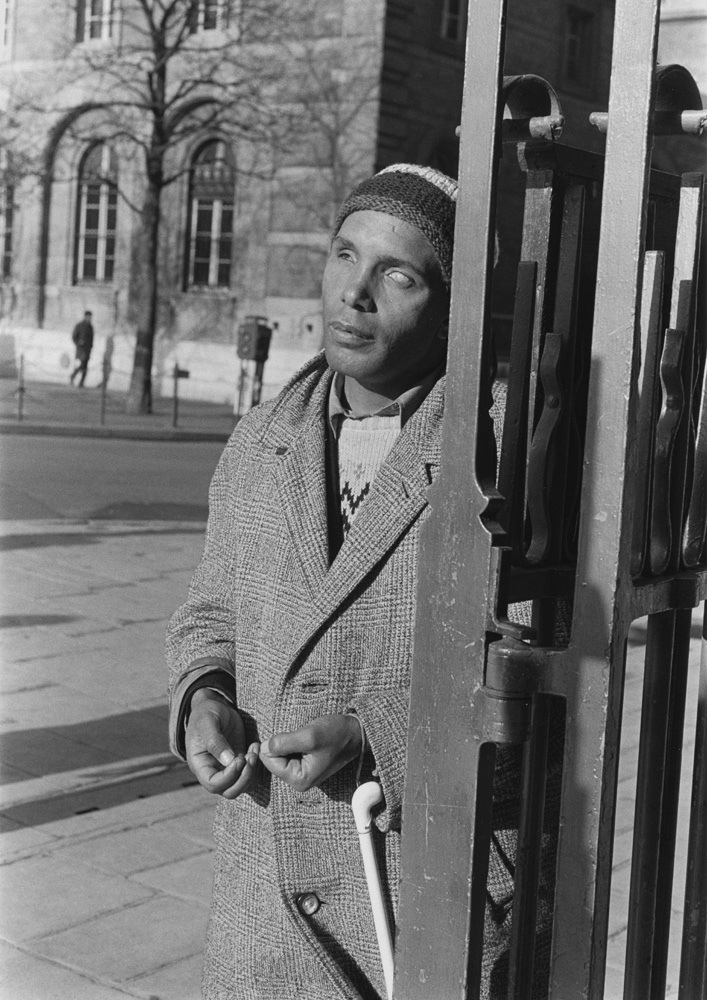

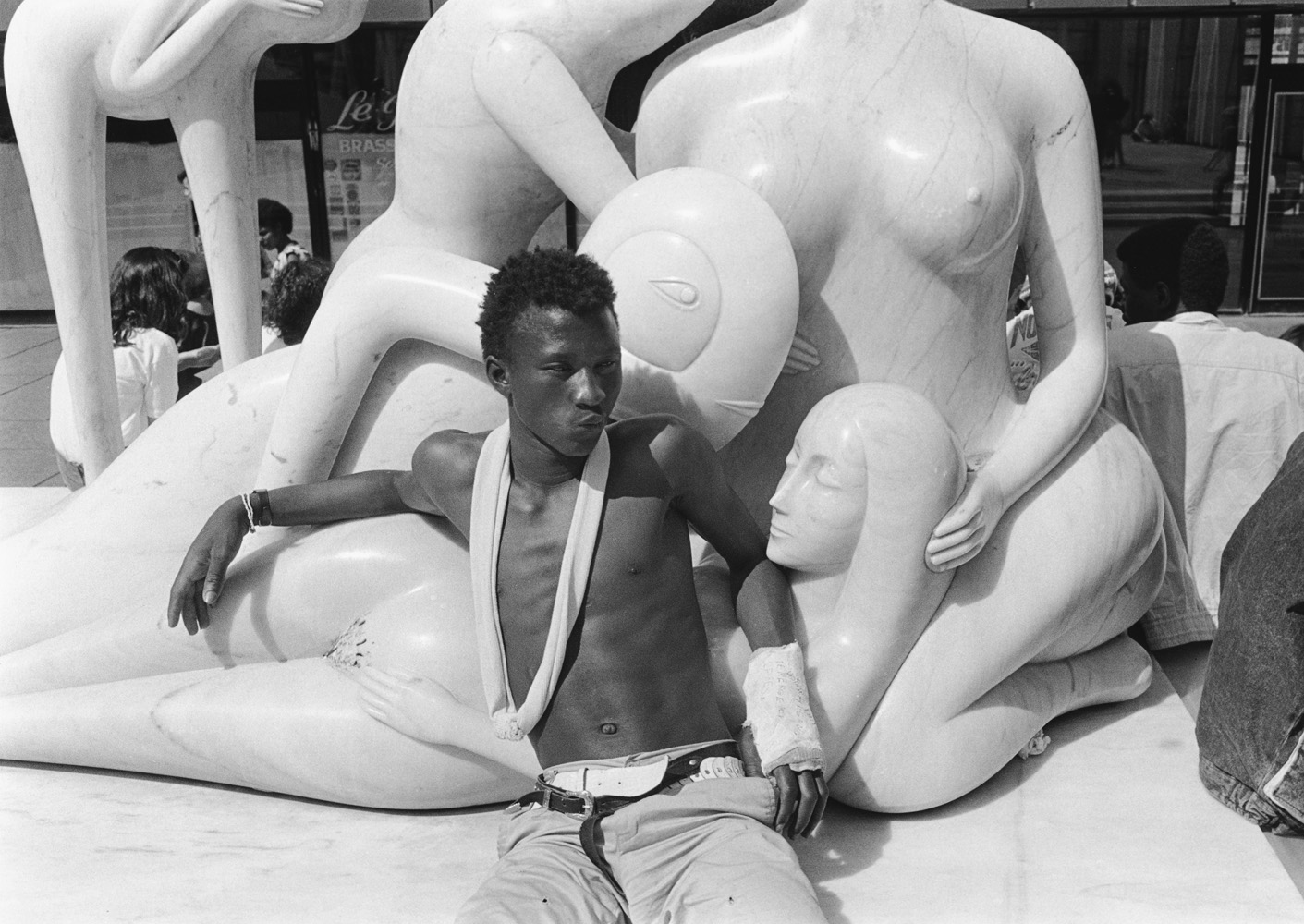

In much of Steinmetz’s work there is a quality that can turn the awkwardness of adolescence into grace. A thin boy with oversized glasses feed birds out of one outstretched hand while, one page earlier, four masked boys (dressed like they stepped from a Helen Levitt photograph from the 1930s) crouch behind a fence of leaves; a young black man with a bandaged wrist effortlessly becomes part of the intertwined figures of the marble statue he leans against; a young girl feeds a fish who breaks the water’s surface with a comically large mouth.

Even though the city plays a role, it is mostly relegated to giving stage to the people Steinmetz is more interested in photographing. The wisps of hair blowing from the head of a blonde woman as she passes on the street grab out attention over the columned facade of the Institut de France behind her; it is the light and the expression on the man’s face who stands near a lake that give us pause rather than the romance of the lake itself with its requisite sailboat and dog lapping at its edge.

These 43 black and white photographs are a humble offering to a very large tradition that started with Nicéphore Niépce and continues today despite tougher French laws governing ownership of one’s personal image. In France individuals have exclusive rights to their personal image and how it is used. This seems almost a crime itself that the city that spurred “street photography” is the first to put a nail in its coffin when the offerings of everyday life can be so meaningful. From the bent knee of Daguerre’s shoe shine to Steinmetz’s saintly little girl peering over a man asleep on a park bench, these are the signs of life offered in the real world — Paris or otherwise.

Mark Steinmetz is a photographer living in Athens, Ga.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com