For Michael Friberg, an editorial photographer based in Salt Lake City, the idea of documenting the plight of Syrian refugees formed out of dissatisfaction. There were already good pictures that had come from the mass displacement, but most were putting their struggles in the same light. “I was frustrated and wondered how I could approach a story like that from a different perspective.” So he did.

Friberg, 27, decided he wanted to try something different by slowing down. He had never been to the Middle East, instead spending time in East Africa, but has always been drawn to refugee issues. Pairing up with Benjamin Rasmussen, a Denver-based editorial photographer who’s spent a lot of time in the Philippines, the two recently spent nearly three weeks in Jordan, where safety from war has brought problems like overcrowded housing, lax integration, employment woes and money troubles.

In May, Friberg pitched Rasmussen, 28. After honing in their research and securing a fixer named Nader, who Friberg crowd-sourced for in a Facebook group where conflict-focused photojournalists share resources, they boarded a flight to Amman in mid-June with their gear and plenty of film.

Neither had collaborated with another photographer before and wanted to avoid recreating each other’s efforts, but they split costs and approached it like other assignments: blending feature stories with formal portraiture and a hint of reportage (similar to Stefan Ruiz and Rob Hornstra).

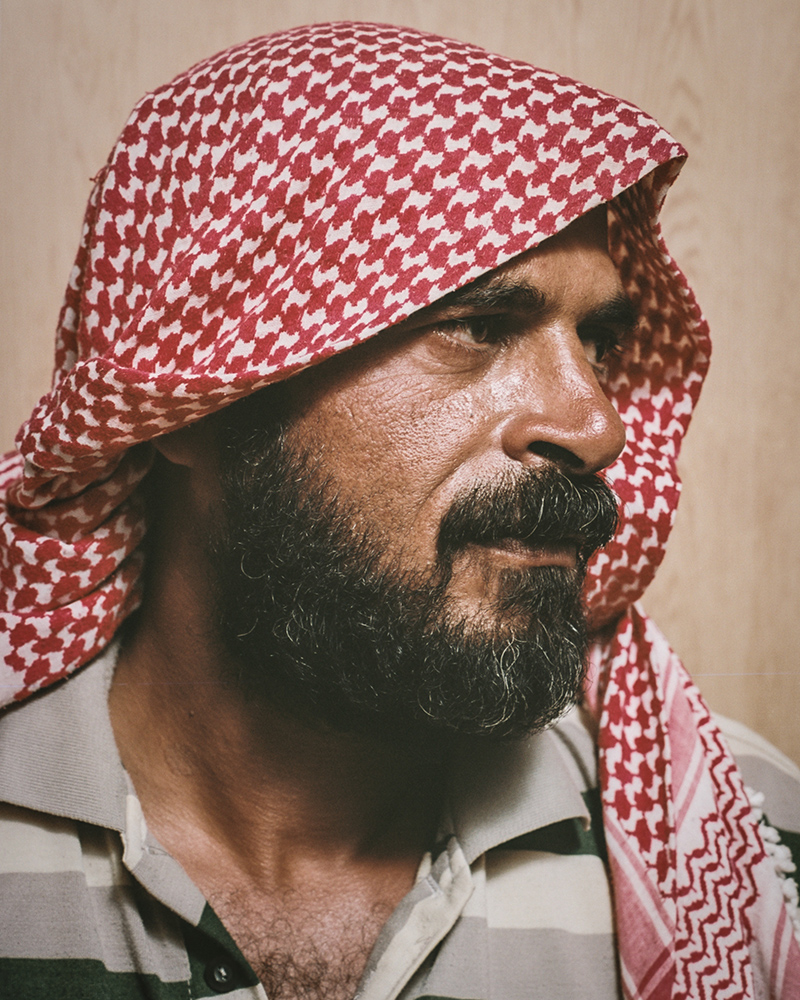

Since both were shooting all film on medium- and large-format cameras, they balanced each other out well. Friberg, who handled most of the interior work and energetic scenes, leans more visceral while Rasmussen, who preferred working in natural light, skews a bit more heady.

After initially shooting in a urban centers, they spent a few days shuffling between Amman and nearby Zaatari, the media-favorite camp near Mafraq along the Syrian border. In just over a year, it’s become the country’s fifth-largest city, holding nearly 150,000 people, and the world’s second-largest refugee camp.

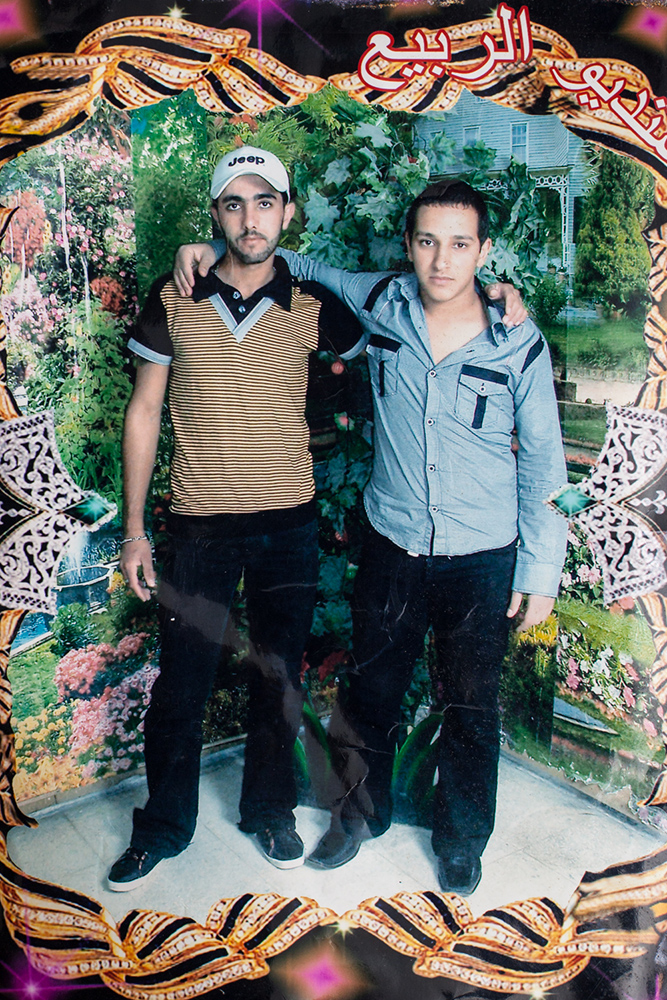

Working there was so tricky, Friberg calls it a “tinderbox.” Not only was it the dead of summer in the dead of the desert, but rampant crime and gangs of unguarded children fueled an undesirable every-man-for-himself mentality. There’s a combative element to it all, too. Some refugees have dealt with photographers snapping at will so much that they’re irritated easily or put on a show, like the young boy posing with peace signs.

“It’s the most cliché thing: it’s this Syrian kid in the American flag shirt and he’s obviously been coached by adults to show the peace symbol,” Rasmussen says. Simultaneously, the picture shows the media-savvy propaganda he and others have been schooled in and the reality of his life in the camp.

The rest of the camp wasn’t much better. While photographing the four Syria-bound buses that leave Zaatari every day, the boarding free-for-all grew so volatile that the photographers shot back-to-back. And during a large scuffle, after Friberg took out his iPhone to digitally capture the scene, it was taken, then returned, then taken again.

The urban areas they shot in were a bit calmer, though more intricate.

Before the trip, Rasmussen was interested in whether Syrians recreated their communities within Jordan, since almost two-thirds of the refugees live outside camps. Instead, they saw fragmentation and isolation. Syrians they met found housing wherever they could, with some leaning hard on Jordanian hospitality for employment, too. But that doesn’t mean refugees weren’t trying to make the best of it.

One family they photographed was living in an apartment in Zarqa, a suburb of Amman. A man named Abdul, who lives in Kuwait but frequently checks on his sisters there, explained to Rasmussen why he planted an olive tree in the backyard: “Look, we did this because we didn’t want to be like the Palestinians, who always say ‘tomorrow we’re going home.’ We had olive trees in Syria so we’ll have an olive tree here.” Although there’s hope of returning home, most are realistic it won’t happen soon.

The photographers recognize the natural limitations of photographic reportage.

“You try to influence the conversation and you try to make sure the important voices are being heard, but at the end of the day, you are one voice in that conversation and you’re not going to be the complete narrative,” Rasmussen says. “As photographers, we tend to have this like cocky attitude that we’ve told the entire story and we’re going to change public perception with this, which I don’t think is impossible, but I think our goals are a little bit more simple.”

Friberg and Rasmussen are gearing up to publish their final project: a newspaper, complete with carefully selected photos and quotations from interviews they conducted with refugees. The two launched a Kickstarter on Aug. 20 to help fund it and have a month to bring in at least $6,000.

But why create a newspaper? They’re relatively cheap to produce and a lot more can be made than a pricey photography book, which might catch more coffee table dust than spur conversation. With a goal of making relatable the people silenced by war who they met and photographed, the mass availability will force their networks—and their networks’ networks—to discuss the work and inform their own communities about the refugees’ reality.

And if, at the end of the day, their readers are more interested the next time they see a news report about Syria, Friberg says, that’s enough for them.

See Friberg and Rasmussen‘s project on Kickstarter here.

Andrew Katz is a reporter with TIME covering international affairs. Follow him on Twitter: @katz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com