In 1959, after nine-year-old Pentti Sammallahti visited the Family of Man exhibition at Helsinki Hall with his father, he announced that he knew what he wanted to do with his life: to be a photographer like his grandmother, Swedish-born Hildur Larsson, whose work adorned his home’s walls.

By age 11, Pentti was making his own photographs — small contact prints of everyday life in Helsinki. He had his first solo show at age 20 and has not looked back since, traveling and photographing throughout his native Finland and across the world. After several retrospectives and exhibitions in more than 20 European countries, Sammallahti is a benchmark figure in Finnish photography and his work is recognized throughout Europe; in the United States, he is far less well-known. Influenced by others’ “artist books,” he has also published a series of sixty-odd books and portfolios, Opus, with both his own work and that of other photographers. In 2004 Henri Cartier-Bresson ranked him among his 100 favorite photographers for the inaugural exhibition of his Foundation in Paris.

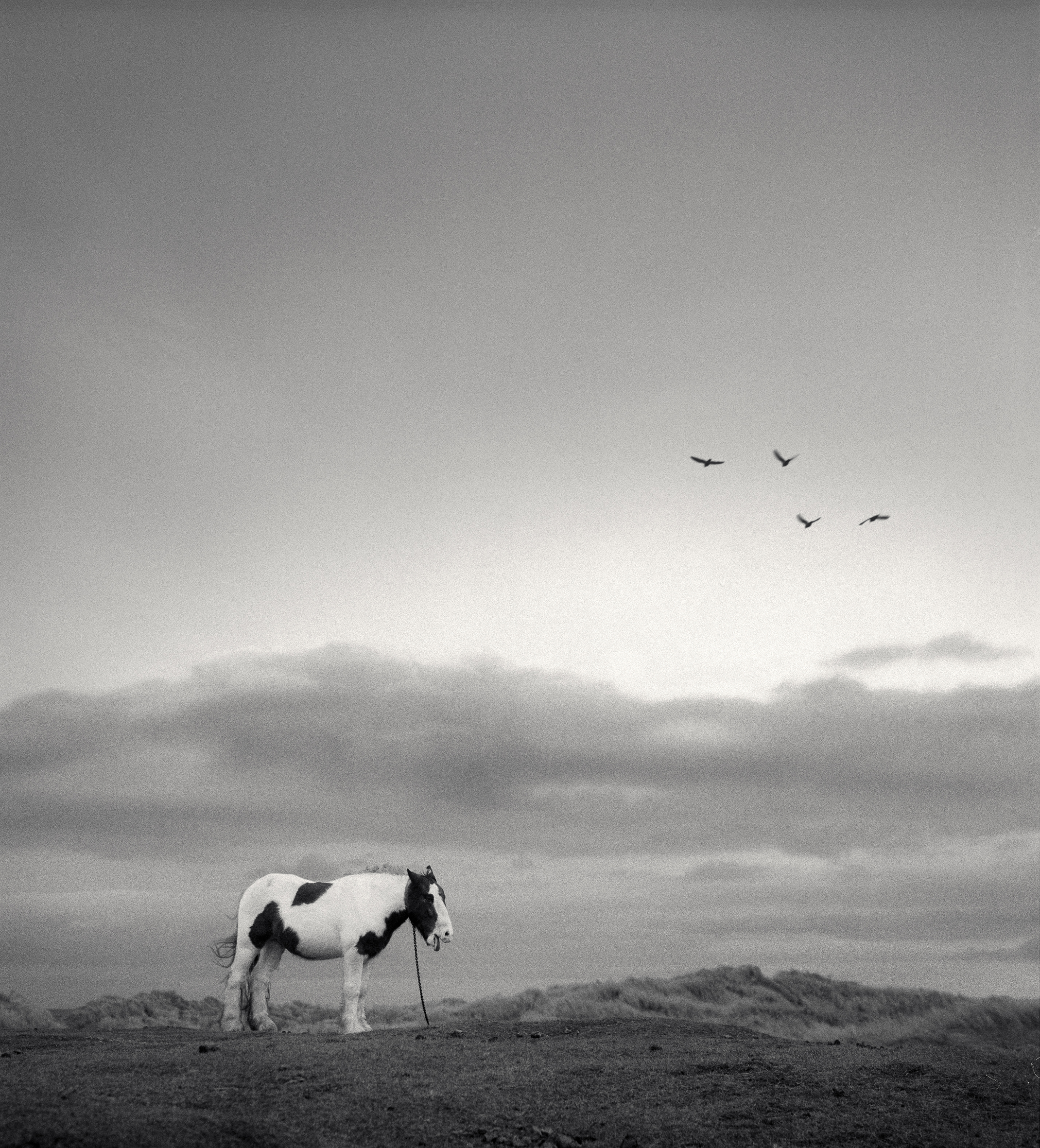

In Sammallahti’s world, humanity is not the center of the universe. His images are fable-like, where animals act as guides. They enable us to pass into another dimension that our usual haste often leads us to ignore. Dogs are among his favorite subjects, and he often carries dried sardines in his pockets as a treat.

The tableaux are striking. A horse stands on a snowy, plowed field near a windmill under a white sky. Two pigeons seem to play seesaw on a tree branch lodged cross-wise on the trunk. Like a mysterious creature of the night, a frog emerges from a pond. Flamingos with twisted necks nest in Namibia’s high grasses. In a forest’s clearing, a white rabbit sits, as if ready to meet Alice. Under a tree’s horizontal branch, a dog stretches in a yoga-like pose, a perfect parallel to the branch. Another dog walks on a village’s snow-covered path, holding a purse in his mouth.

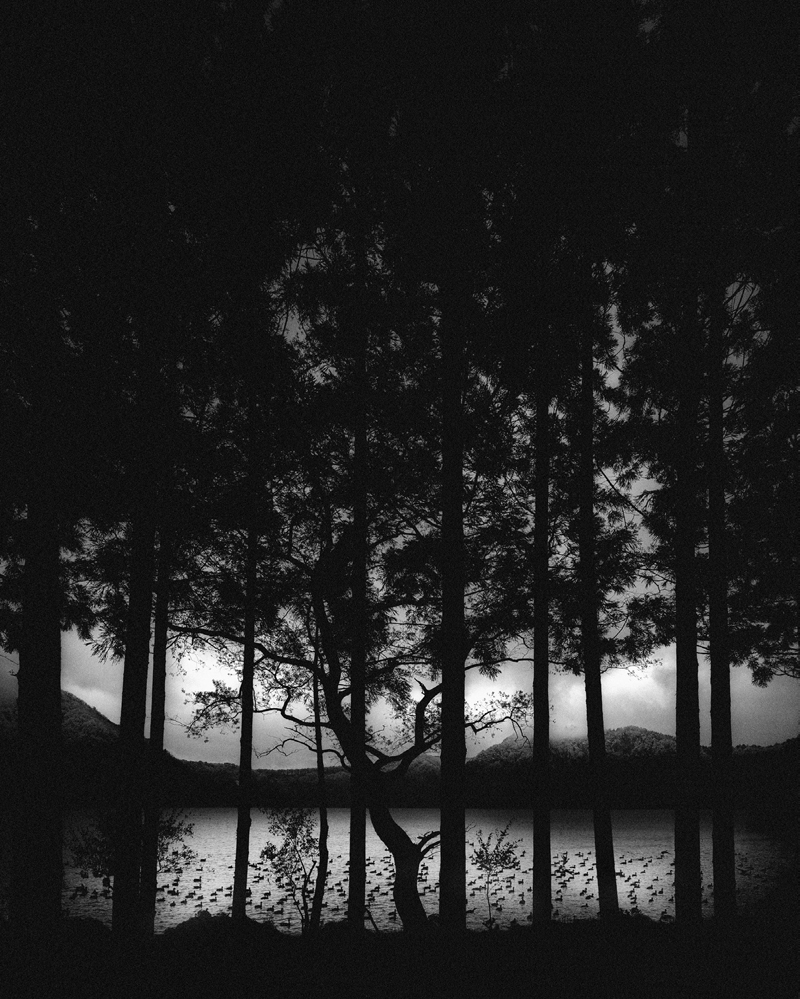

Sometimes the images are free of animal or human presence. In large panoramic pictures, branches of trees snake and swirl. Square seascapes confront water and horizon in different shades of grey. The sea stretches like a wrinkled elephant skin, or high waves break into a wall of milk-white foam.

As modest in size as it is in price, his work is a welcome counterpoint to the giant color prints that populate much of today’s market. For Sammallahti, small is beautiful.

“Darkroom work is as important as shooting,” he says. “I am a craftsman.”

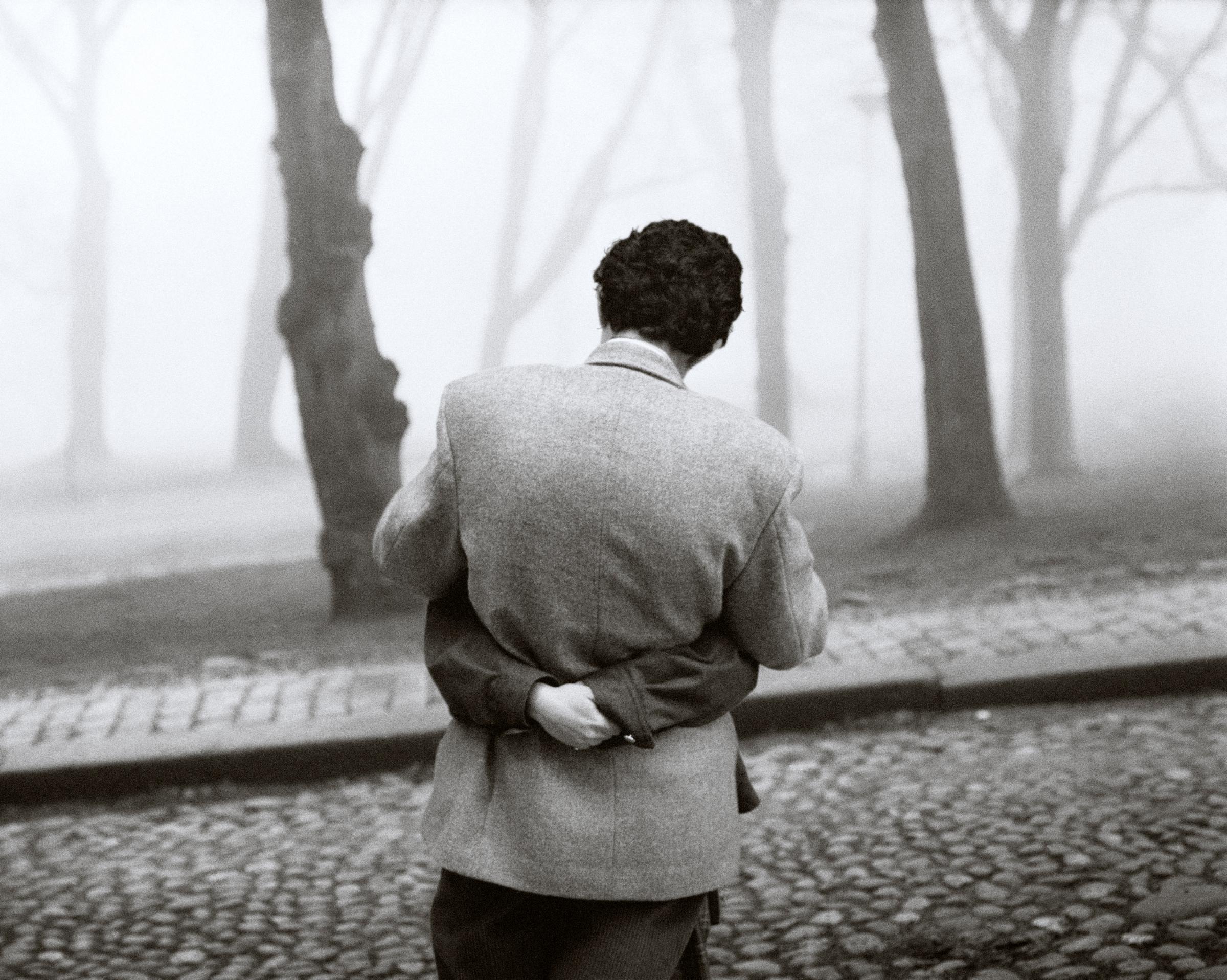

Sammallahti likes rain and snow, sleet and darkness. “I wait for photographs like a pointer dog,” he says. “It is a question of luck and circumstance. I prefer winter, the worse the weather, the better the photograph will be.” His favorite time of day is dusk, and the mysterious light — Entre chien et loup in French, meaning “between dog and wolf” — accentuates the feeling of a world whose fragile beauty is menaced, perhaps even on the cusp of disappearing. If we don’t pay attention to our connection with nature, he seems to say, something vital will be lost forever.

Sammallahti’s spiritual family could include Basho, the wandering Japanese monk, Lewis Carroll, La Fontaine, Paul Strand, André Kertesz and Josef Koudelka. His delicate palette of whites, greys and blacks evoke all the senses, often focusing on textures — as in an image where dry stalks of grass poke through an immense field of snow.

“Finding myself on a rocky island,” he notes, “I suddenly understood what the stone near me, the ship on the shore, the cloud navigating the sky and the salient, sporadic calligraphies drawn by migrating birds were telling me… Then I understood that you don‘t take photographs, you receive them.”

His pictures are small revelations; the longer you watch them, the more you discover. Like haikus, their silent, austere intensity captures and links disparate elements of reality. They demand our attention to the instant, draw us into their world, which becomes ours: here, far away.

Nailya Alexander Gallery, 41 East 57th Street, New York, offers a permanent installation of Sammallahti’s work, and is exhibiting Here Far Away through April 27.

Carole Naggar is a photo historian and poet. She recently wrote for LightBox on Chim’s images of children in Europe after World War II.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com