In 2003, a young American historian named David Shneer was conducting research in Moscow when he heard about an exhibition of photographs called Women at War. At the time, displaying photography on gallery walls was still a fairly novel concept for Russia, and the exhibit was not meant to be a blockbuster. To get inside, Shneer found that he had to ring a doorbell at a nondescript building, at which point a raspy voice came over the intercom and demanded: “Who are you? What do you want?” But the images inside astounded him.

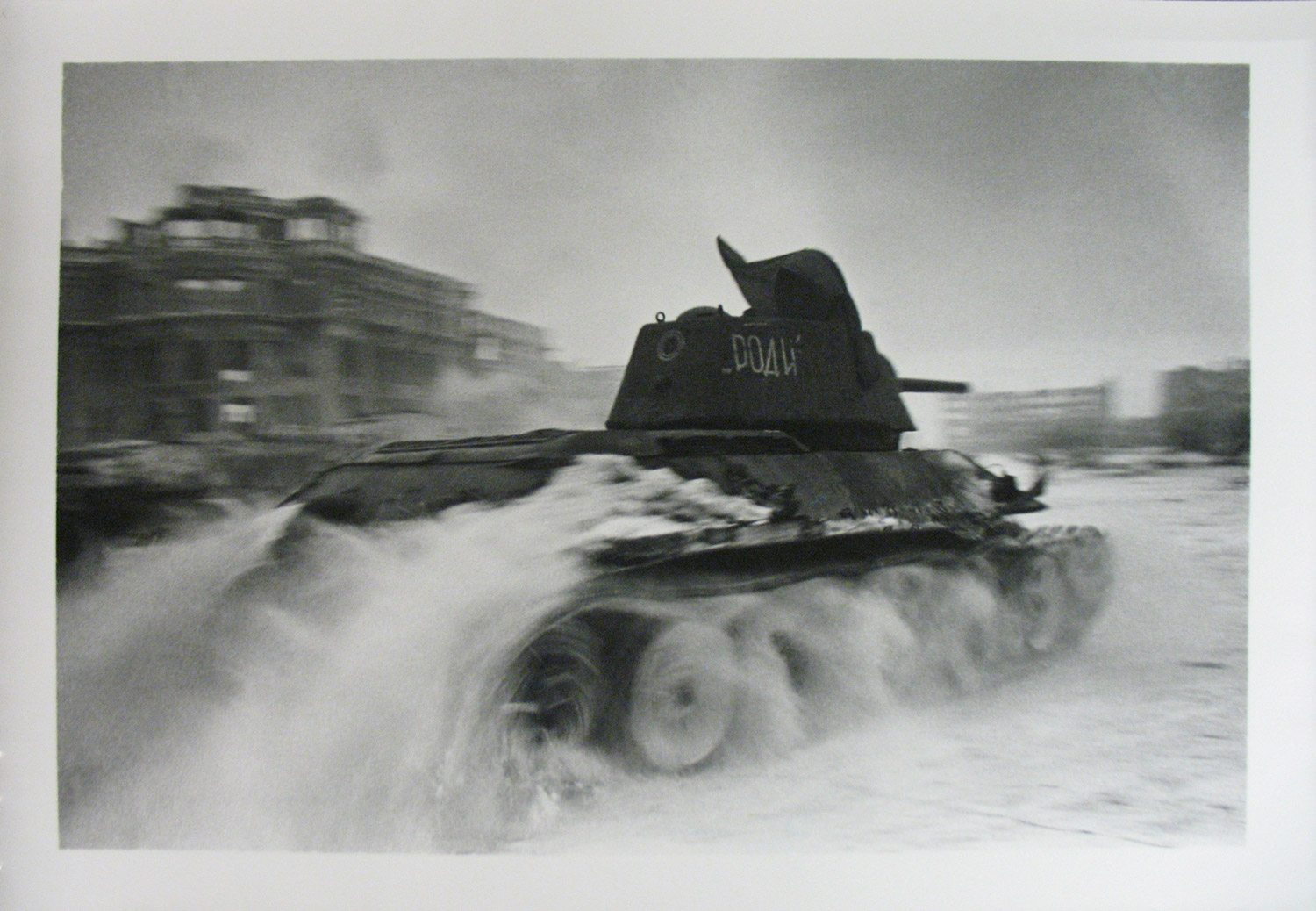

Not only had they been taken with incredible skill—arranging light and form in a way that would put to shame many of today’s war photographers—but they were from the Soviet battlefields of World War II, which made the surnames of their authors seem all the more strange. About four out of five of them, Shneer noticed, were Jewish surnames. “How is it possible,” he thought, “that a bunch of Jews, who are supposed to be oppressed by the Soviet Union, are the ones charged with photographing the war?”

As delicately as he could, Shneer put the question to one of the curators, who in typical Moscow style had a glass of wine in one hand and a cigarette in the other. “She looked at me like I’m an idiot and said, ‘Yes, the photographers were all Jewish.'” It turned out she was the granddaughter of one of them, Arkady Shaykhet, and their conversation that day is what led to the exhibit that opened on Nov. 16 at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. It has the same title as the book Shneer wrote from his research—Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War and the Holocaust.

The show explores the way World War II was covered in the pages of Soviet newspapers such as Pravda, casting light on a side of the Holocaust that often gets short shrift in western history books. The genocide against the Jews, usually associated with images of Nazi death camps and gas chambers, was also perpetrated through mass shootings across Eastern Europe. Later termed the “Holocaust by Bullets,” it took more Jewish lives than the concentration camps, says Shneer, and it was documented most poignantly by the Jewish photographers of the Soviet press.

Although none of them are still alive to tell their story, Shneer spent the better part of a decade tracking down their relatives in Moscow and collecting nearly 200 works from their family archives. The prints were often no bigger than a pack of cigarettes, taken with beat-up cameras and two roles of film allotted for each battle. There are more faceless soldiers in these frames than intimate portraits of victims, and the most common theme is emptiness, at once bleak and monumental. But given their historical context, what seems most striking is the duality that runs through the lives and works of these photographers. On the one hand, these are works of Soviet propaganda, glorifying the Red Army in the tradition of socialist realism. “They needed photos of nurses doing good work on the home front, patriotic soldiers conquering territory,” says Shneer. “And their Jewishness rarely appears in that kind of material.”

But it does appear when they go off assignment to explore the Jewish ghettos in places like Ukraine and Hungary. There they found survivors living among the ruins of Europe, the yellow Stars of David on their overcoats still marking them for death. In the Budapest ghetto, the photographer Evgenii Khaldei found the corpses of his fellow Jews strewn about the floor of a gutted shop, a scrap of butcher paper covering the face of a man whose body lies in the doorway. Images like this did not appear in the mainstream Soviet press, but they were published in Eynikayt, or Unity, the Yiddish-language newspaper of the USSR. “We have this image in our heads that Jewishness was completely suppressed in the Soviet Union,” says Shneer. “But that’s really a post-war image of the country.”

Antisemitism only became part of Soviet dogma in 1948, the year that Israel was founded and Josef Stalin began his campaign against the ”cosmopolitans” — a Soviet byword for Jews. Many of the best Jewish photographers lost their staff positions at Pravda and other major publications that year, and phrases like “too many Jews on staff” began appearing in the official correspondence between the editors and their government censors. Some of the photographers continued working as freelancers for the propaganda press, but even after their experiences on the front, they rarely embraced their heritage. “None of these guys were buried in the Jewish cemetery,” says Shneer. “None ever tried to leave for Israel. None learned Hebrew.”

Soviet patriotism and its predilections came first, in their lives and in the work they produced. Even long after the fall of communism, when Shneer was conducting his research, the last surviving photographer from this group refused to meet with him. “He was still living in the Soviet world where meeting with a foreigner was scary.” In their style and execution, the images they captured are rooted in that world. They document the greatest triumph of the Soviet Union. But regardless of whether they are viewed on the pages of Pravda or a gallery wall, that world does not bind their relevance as monuments and works of art.

Simon Shuster is TIME’s Moscow reporter.

Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War and the Holocaust will be on view at the Museum of Jewish Heritage from Nov. 16 2012 to April 7, 2013.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com