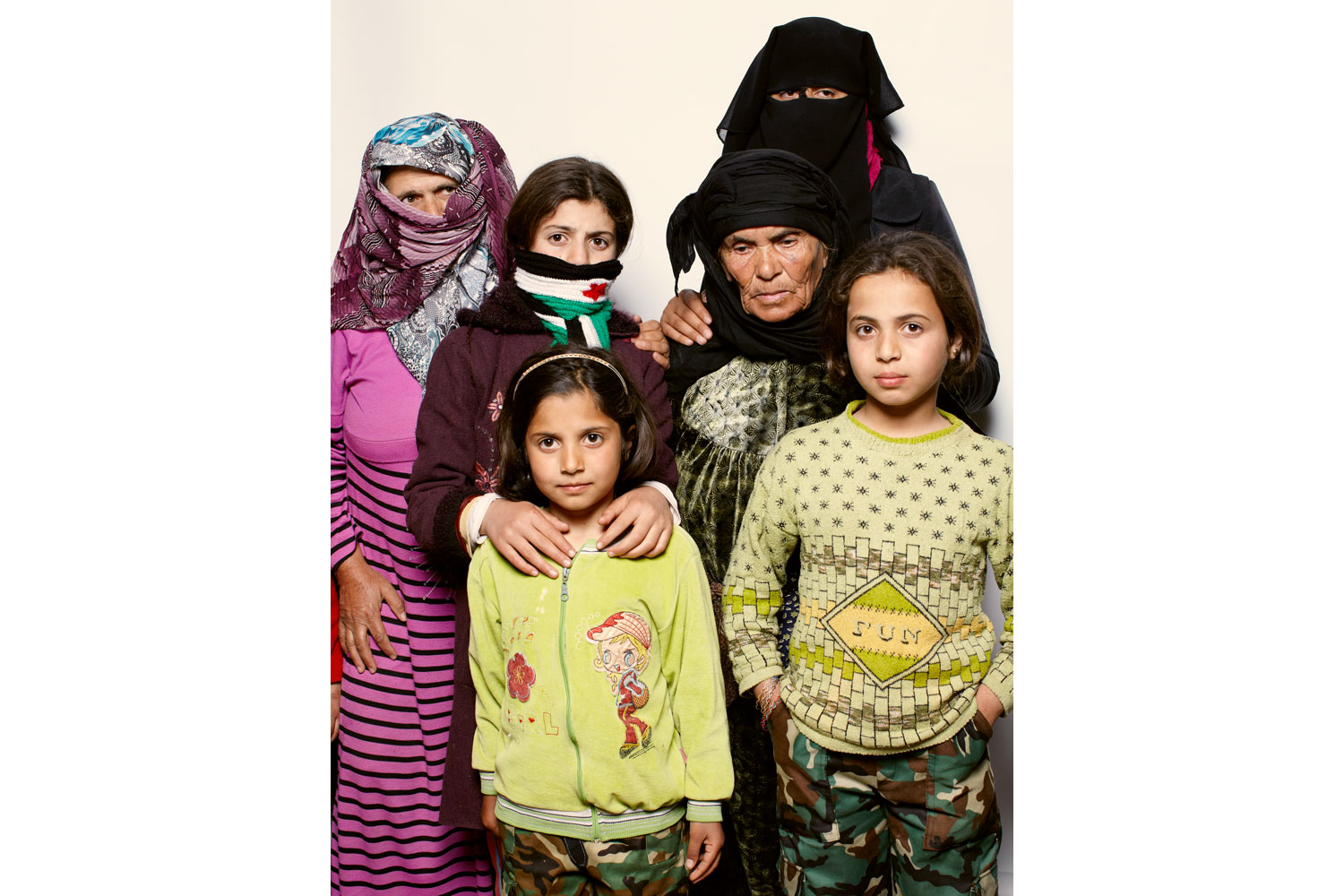

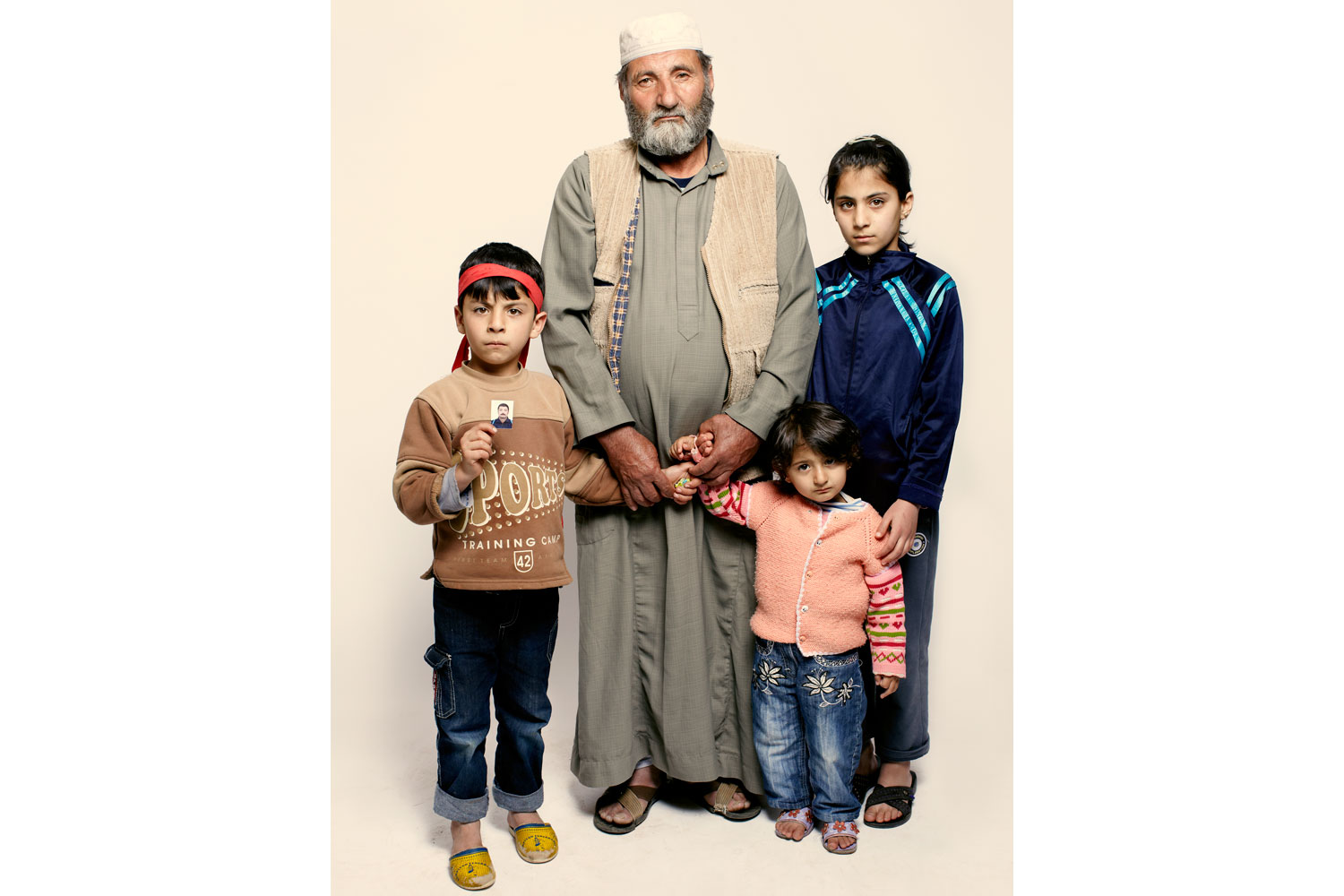

It was approaching midnight but many of the hundreds of Syrians who had arrived at the Reyhanli refugee camp in southern Turkey just hours before were still restless, even the toddlers. Most were concerned with where they were going to sleep that night, and if friends and family members had reached safety. It was difficult to get people to talk. Many were afraid to speak for fear of reprisals against relatives still in Syria, others were clearly physically and emotionally worn down. Nevertheless, some were prepared to share their experiences, their fears and thoughts.

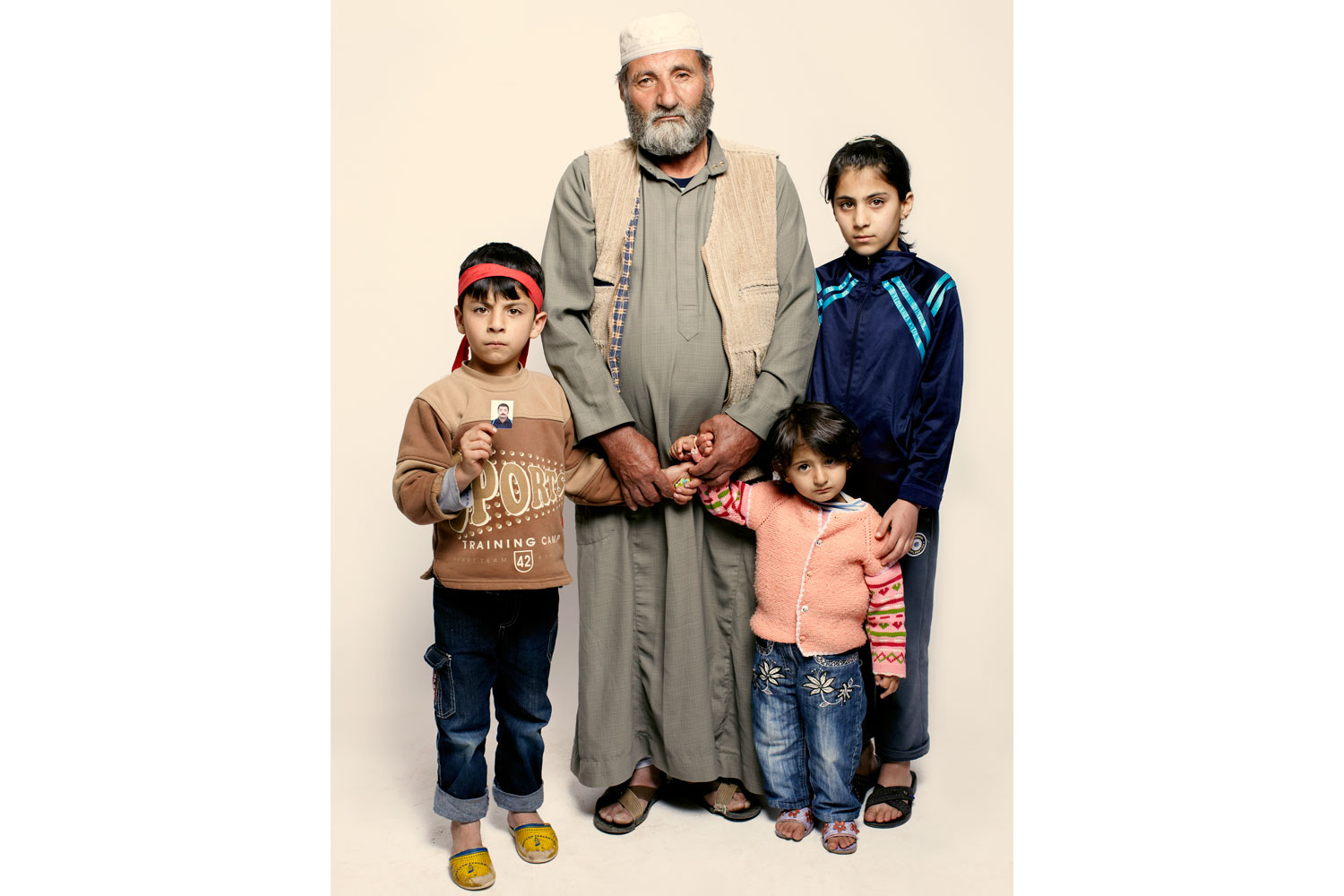

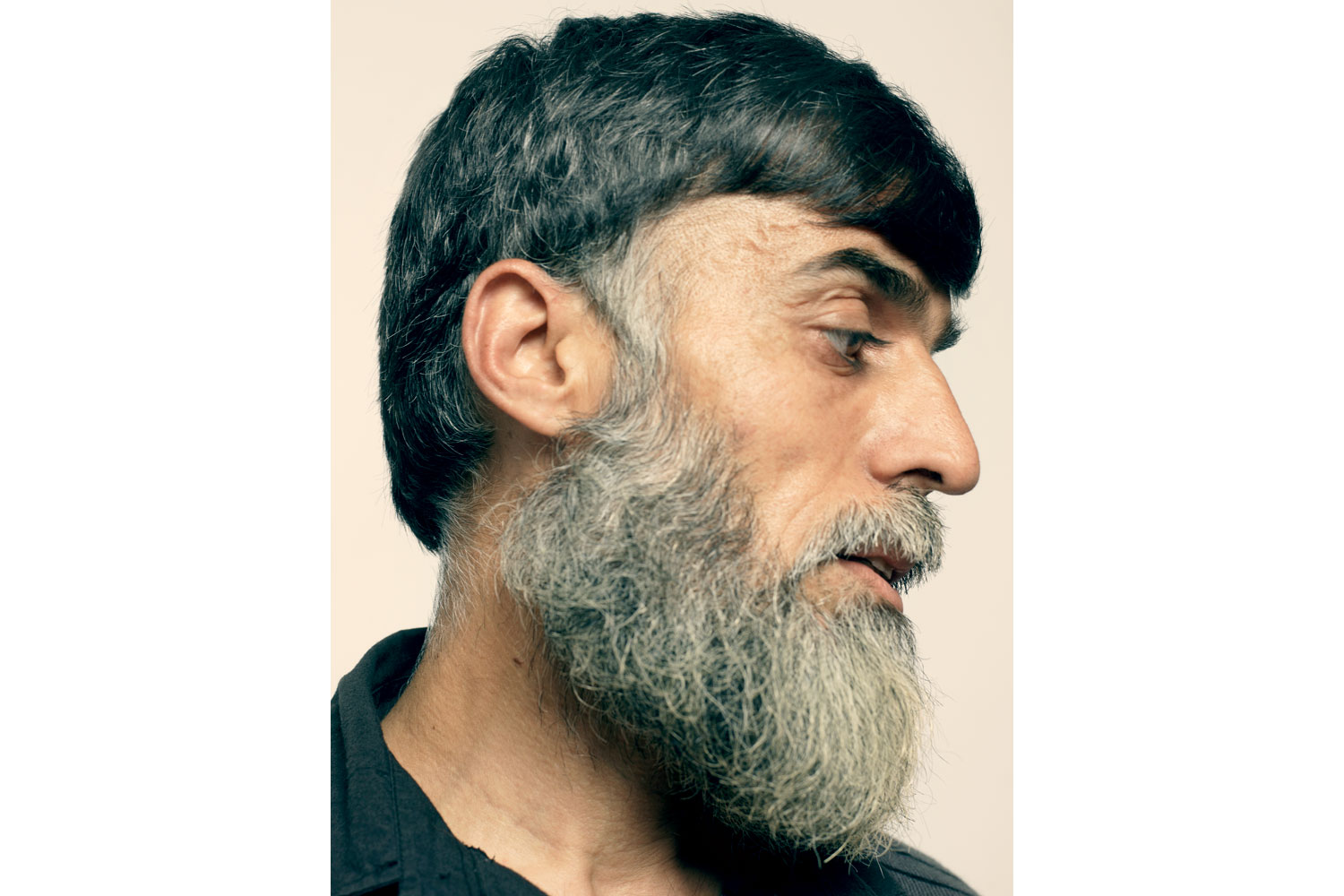

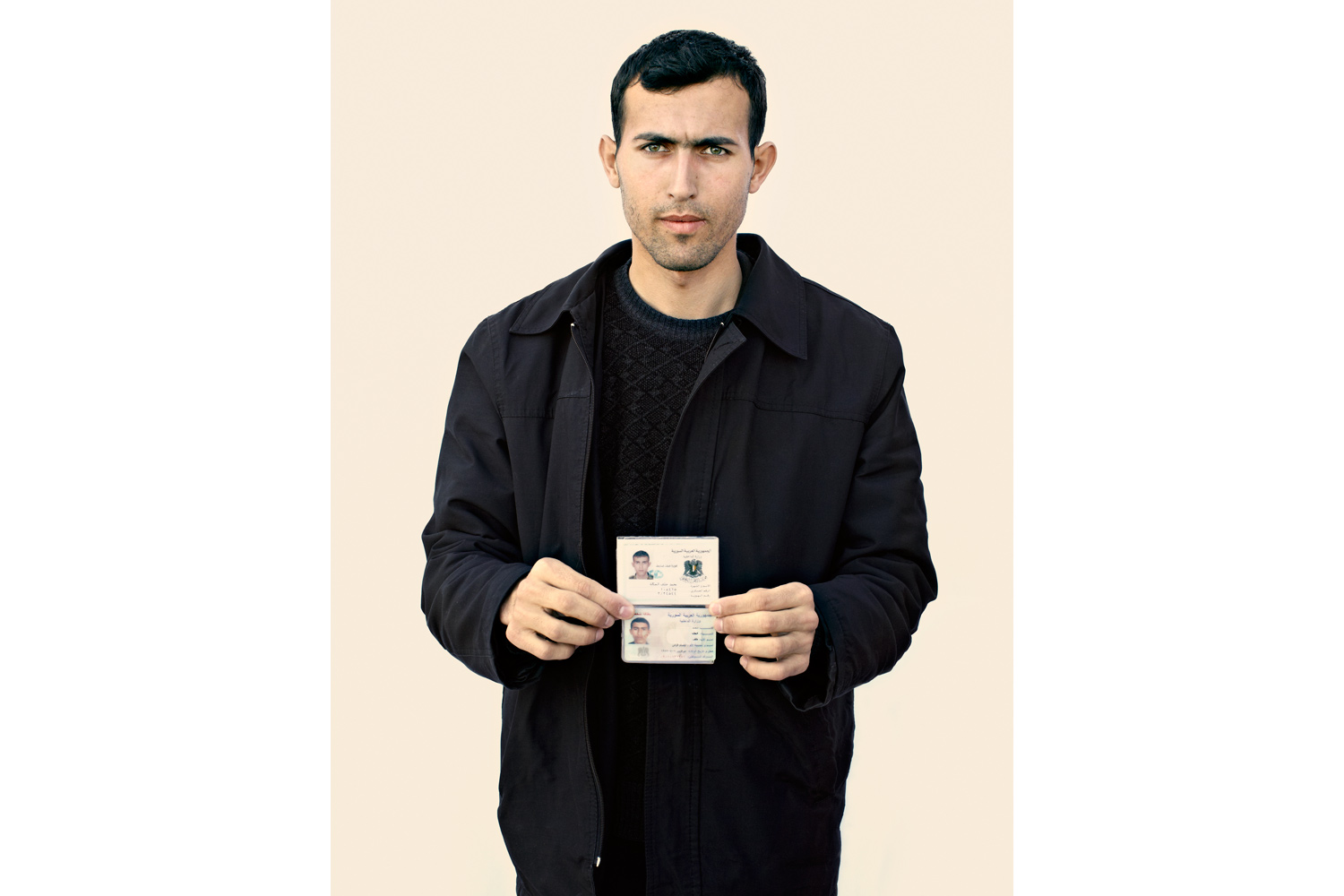

TIME was granted vast access during the first week of April to the Reyhanli and Yayladagi camps in Turkish territory to document, through words and pictures, the travails of the thousands who were fleeing Syria. As photographer Peter Hapak and his assistant took portraits of several of the refugees against a white backdrop set up just beyond the tents, other residents of Reyhanli—both newcomers and those who had been there for months—swirled about.

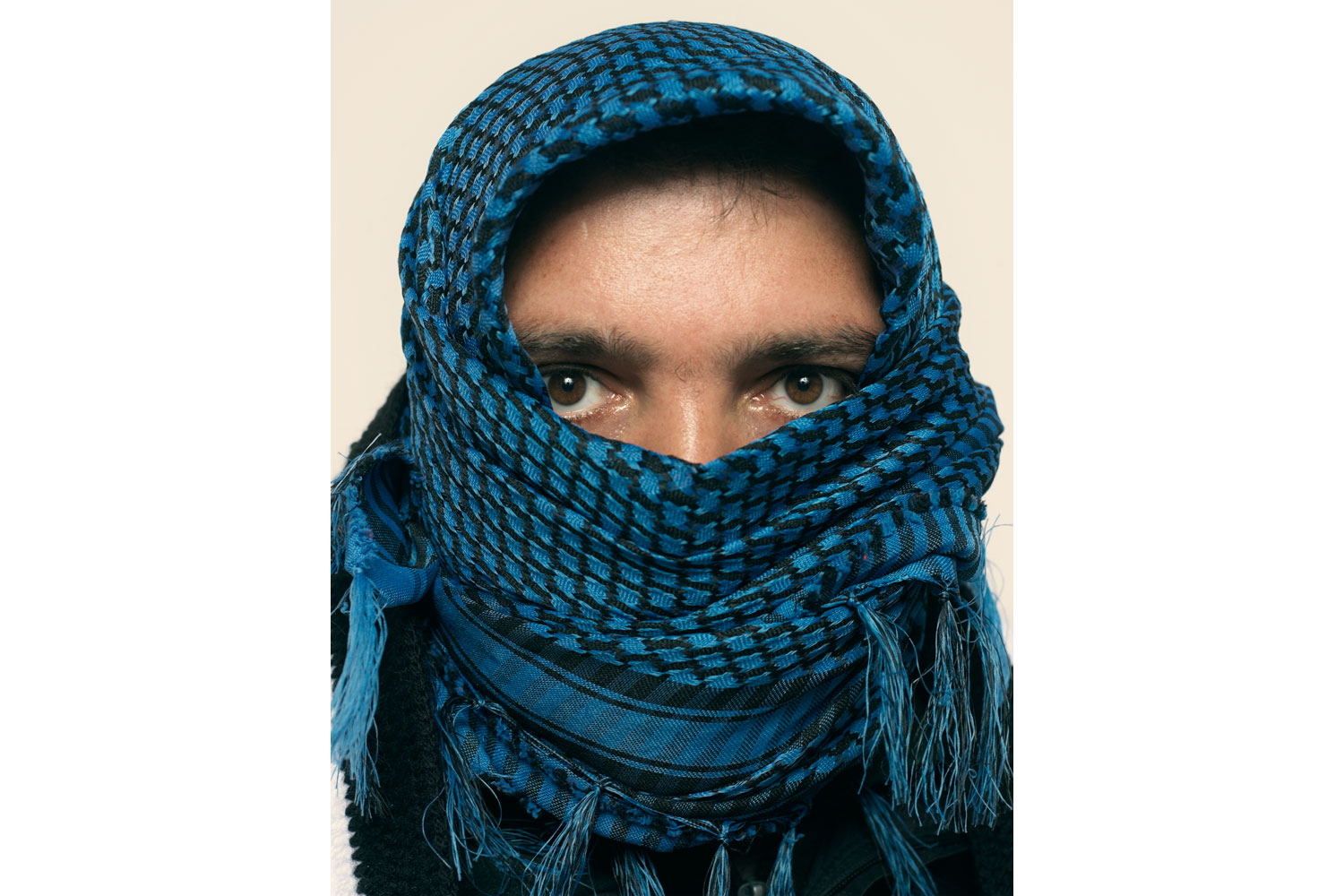

A wiry young newlywed in a thin aqua blue zippered jacket was searching for his wife among the families milling around the cramped canvas tents. His Syrian border village of Kili in Idlib province was shelled and strafed by helicopter gunships that morning, an account repeated by many of the other refugees from the town. The 26-year-old with a thin mustache and enraged eyes was seething: “I buried a man today. Two others and me, we buried a man who had half of his head missing.” When the young man, who refused to give his name, returned to his house after the burial, his wife wasn’t there. Believing she had fled across the border, he headed for Turkey as well. “Now, I learnt from others who arrived after me that my family was behind me, that they have reached the border but haven’t crossed it yet.”

Like so many others in Reyhanli that night, the young man had made a perilous journey on foot through mountainous terrain to reach Turkey, guided and aided by members of the rebel Free Syrian Army along backroads and mountain trails to avoid Syrian President Bashar Assad’s troops. Some had walked for hours; others for days; most brought nothing but the clothes on their backs and harrowing tales of what they had fled. They spoke of mass killings, of homes being shelled, burnt to the ground, of relatives marched in front of tanks as human shields in the village of Taftanaz.

“Assad’s army is trying to find us, they are hunting us down in these hills to shoot and kill us,” the young man said. His group, however, was lucky. It did not encounter Assad loyalists. Just days later, a Syrian refugee was killed and several wounded after Syrian troops fired across the border at a refugee camp in the Turkish town of Kilis after a skirmish with rebel fighters. It wasn’t the first time the regime’s firepower had chased its opponents across borders into Turkey and Lebanon, but where the Lebanese government has been pliant and weak in its response to the attacks, Turkey’s patience is waning. The country already houses more than 24,000 Syrians, and is expecting thousands more.

In just one day last week, more than 2,800 Syrians streamed into Turkey from Idlib, the highest 24-hour figure to date. The exodus belied President Assad’s pledge to adhere to an internationally backed ceasefire agreement brokered by joint United Nations-Arab League envoy Kofi Annan. The deal called on Assad to withdraw his troops and heavy weaponry from besieged cities and towns by Tuesday April 10, and for both sides to cease violence. But instead of winding down, the regime’s muscle escalated operations to crush the year-long revolt.

Syria has routinely ignored diplomatic deadlines and scoffed at half-hearted international ultimatums, relying on its Russian and Chinese allies to shield it from censure. But this time, Assad’s powerful friends signed off on Annan’s initiative. His dismissiveness may yet chip away at their support, or at the very least make it harder for them to insist, as they have, that the Syrian president must be part of any diplomatic solution.

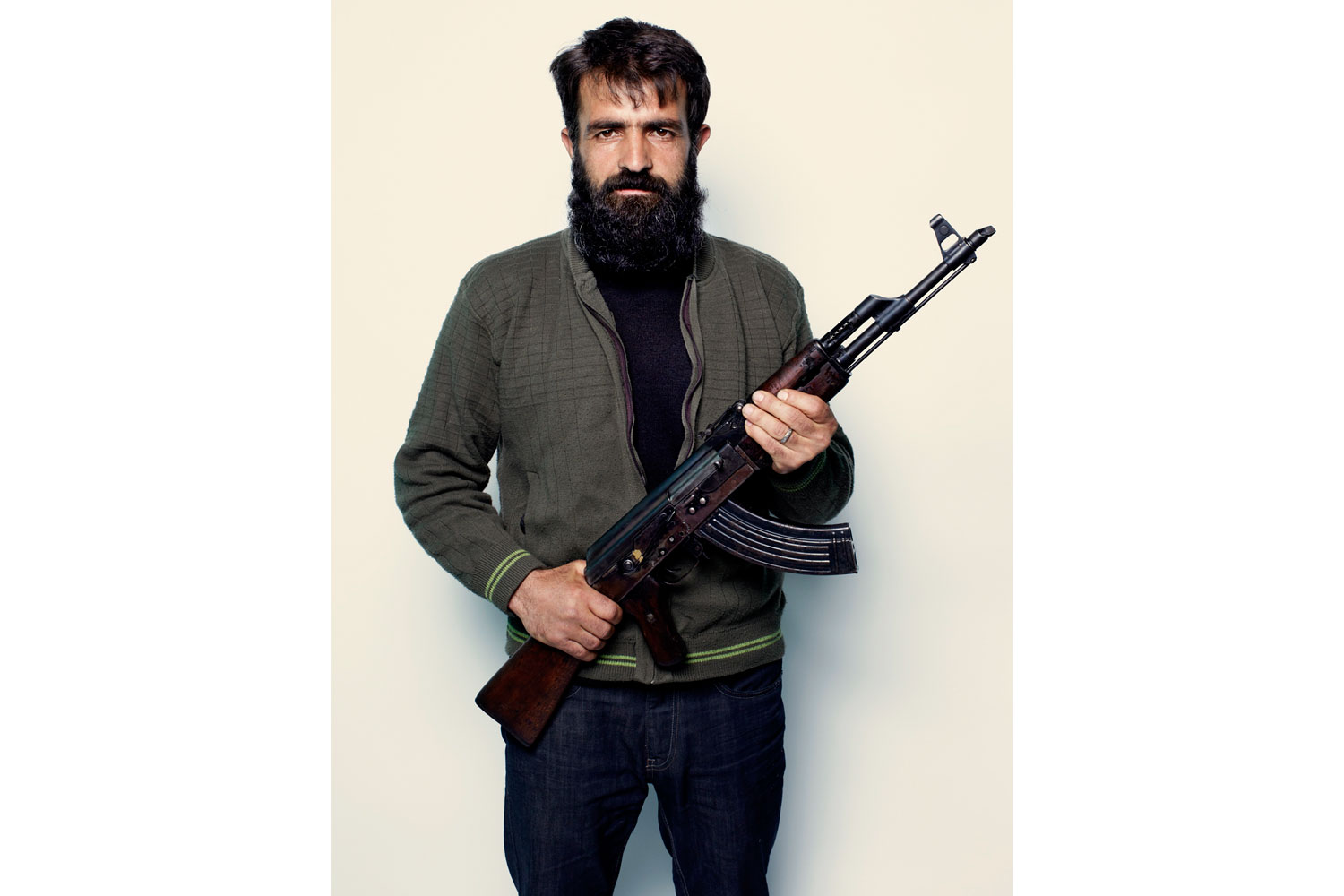

International discord is one thing. The disunity among the opposition to Assad is another. The Syrian National Council, the main opposition group in exile, remains divided and beset by claims of corruption, personal pettiness, feuds and rising suspicion that its secular leader Burhan Ghalioun is merely a front for the powerful Islamists. The nominal military leadership of the Free Syrian Army isn’t in better shape. Corralled in a camp in Apaydin, they have offered little to the men fighting and dying inside Syria in its name.

In the real struggle, within Syria, it has always been a revolution of ordinary people, of farmers and taxi drivers turned armed rebels, of students and laborers who have become community leaders. But, if the accounts of the refugees in Turkey are any indication, these revolutionaries despair of receiving the help they need to beat Assad. Early on, they had baptized their uprising a “revolution of orphans,” bereft of support. As he scurried away with a thin foam mattress tucked under his arm, one man said, “Before we thought that the world didn’t know what was happening to us, now we realize that you do and you don’t care.”

“We only have God and our own hands!” said another man, who had been standing nearby. It was a view shared by many. Said the young man searching for his wife: “Tanks we can stand in front of, we can try and stop them, stand in front of them, die as martyrs, but how can we stop a helicopter? We are now in Turkey, we don’t want to be here.” Growing more agitated, he says, “We want weapons, we want to fight… We want weapons, we want weapons, we want weapons.”

More: Syria’s Year of Chaos

Abouzeid is a Middle East correspondent for TIME. Follow her on Twitter at @raniaab.

Hapak is a contract photographer for TIME. In December of 2011, Hapak photographed The Protester, TIME’s Person of the Year.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com