There are some terrific photographers in the Museum of London’s current exhibition, London Street Photography. The photographers range from John Thomson, who was a 19th-century pioneer in this genre when long exposure times and bulky cameras made such photographs minor miracles, to Nick Turpin, who founded the website In-Public in 2000 to give contemporary practitioners a place to congregate and keep the genre going. Turpin’s is classic work that catches the chance juxtapositions and silly associations on which hand-camera street photography has thrived since Henri Cartier-Bresson was declared a boy genius by the Surrealists in the 1930s. Thomson was an inventor of the genre because he risked his laborious equipment on frivolous moments, like the one at which a little girl came skipping by “Hookey Alf,” a worker who had lost a forearm in an industrial accident. Thomson was prescient enough to realize that instead of ruining an exposure, some motion blur or other aberration could be the very making of the picture. He was an aberration himself, a motion-blurred leap into the future of photography that would contain Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans and Robert Frank.

Among the photographers who come between Thomson and Turpin in this exhibition are a couple I hadn’t known before whose work I’m pleased to catch up with. One is Lutz Dille; originally from Germany, he became by the 1960s a globe-trotting street photographer who did some memorable work in London. These are close-in, confrontational sidewalk portraits of unwilling, willy-nilly subjects. The work owes a lot to two series that Walker Evans did for Fortune magazine in the 1940s, but this doesn’t diminish it. Like life on the street, which is in the public domain (despite some recent legal challenges to that idea), the inventiveness of one street photographer is freely passed to his or her successors to make of it what they can.

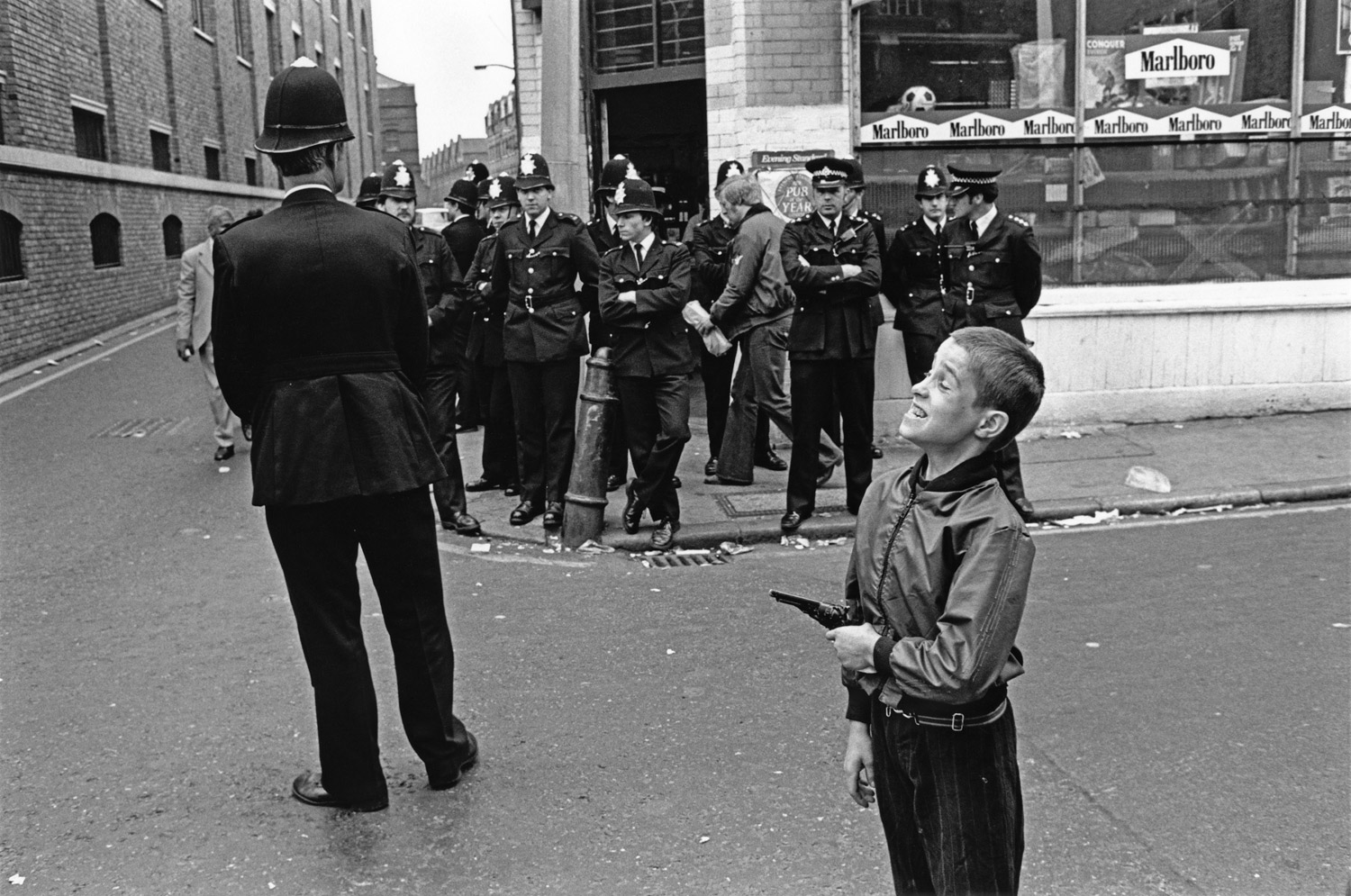

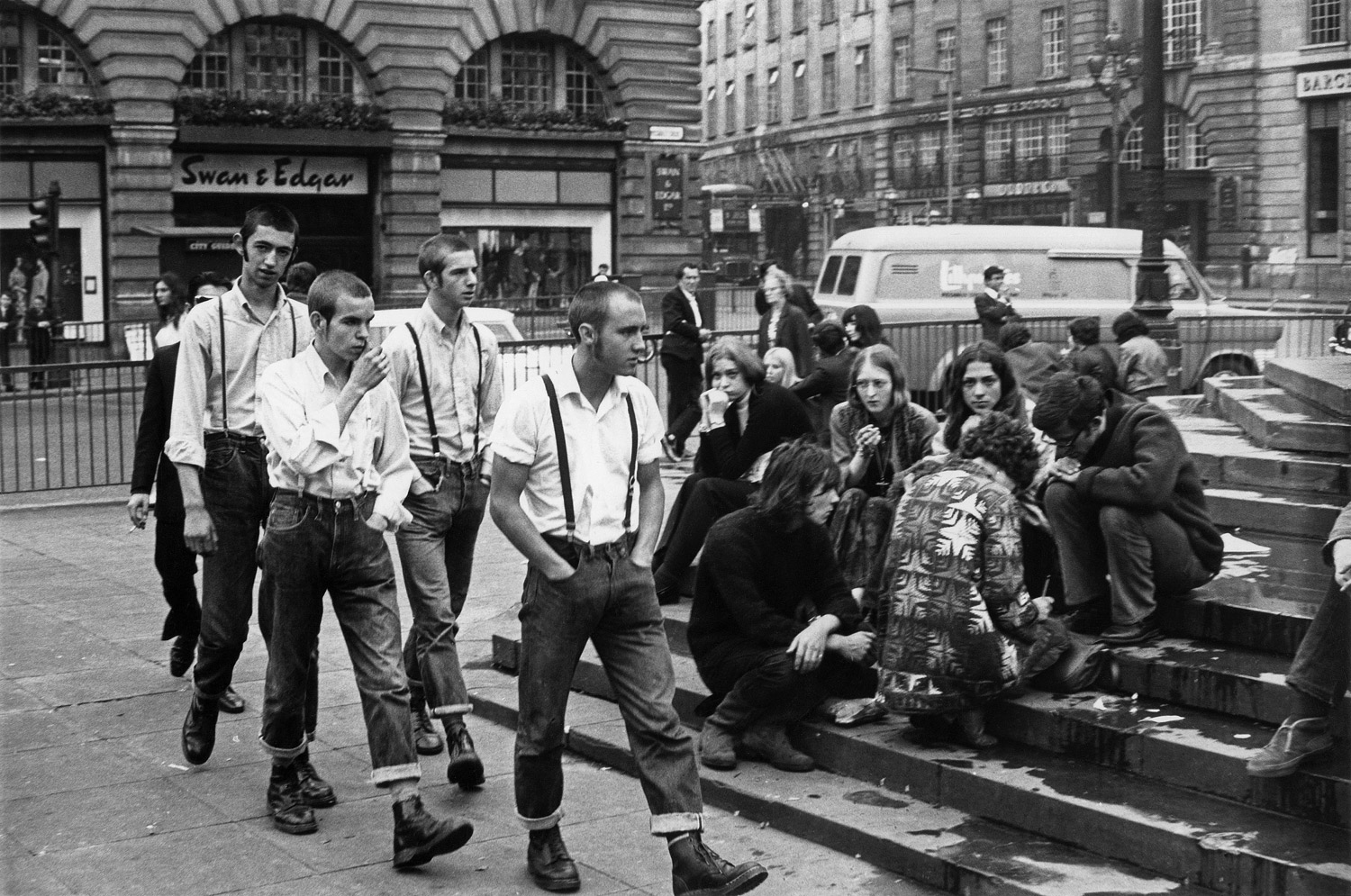

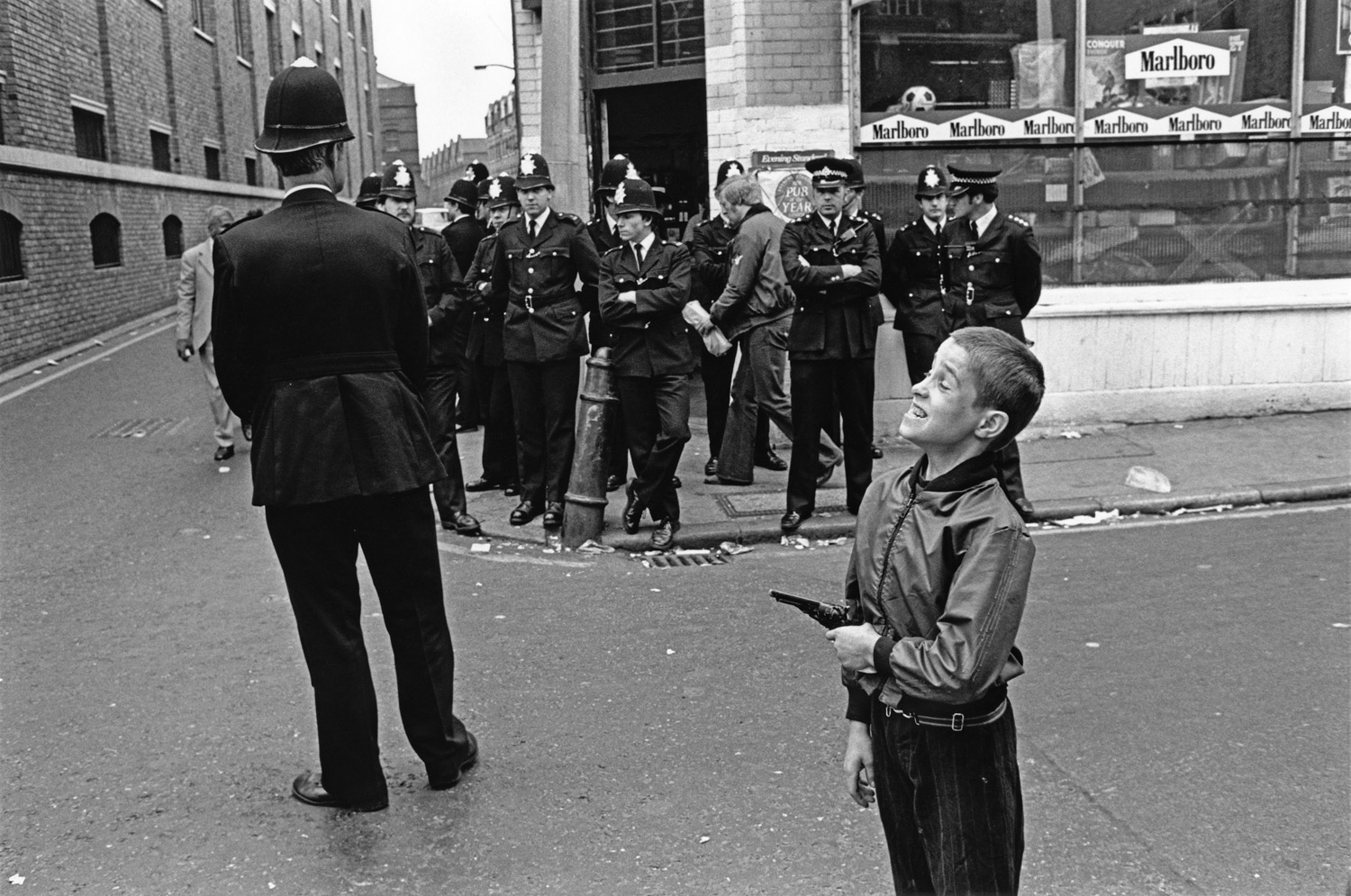

An even more recent street photographer new to me is even better—Paul Trevor, born 1947, who was a founder of the photo collective Camerawork and spent 20 years documenting the Shoreditch community in which he lived. One picture alone by him is worth the price of admission, an image of a foggy street lined on both sides by mysterious facades whose windows reveal that there’s nothing behind them. Traversing this Daliesque landscape is an equally strange, forbidding figure concealed beneath a black cape and hood straight out of a gothic fairy tale. Trevor fits a pattern among the British street photographers I do know from Turpin back to Humphrey Spender in the 1930s.

Like Trevor, Spender and Turpin are both notable for having been instrumental in a collaborative documentary project. As with Turpin’s contribution through his website In-Public and Trevor’s through the collective Camerawork, Spender’s came through his association with a group effort called the Mass Observation. This was a Depression-era undertaking comparable in some ways to America’s Works Project and Farm Security Administrations, both of which had photographic units whose impact on photo history was enormous. The difference is that the British counterparts weren’t government-sponsored, nor were the results widely disseminated. In the British tradition of amateurism, these were voluntary photographic projects done in one’s spare time, with the consequence that the work wasn’t widely known or even published until years afterward. It therefore had only limited impact on Britain’s photographic history.

Though the work by Spender included in the exhibition isn’t from the Mass Observation, some of it is from the same period; and the same lapse in history represented by his career or Trevor’s is also found in that of an equally good 1950s photographer the exhibition contains, Roger Mayne. Because he worked completely on his own without group affiliation, documenting a London neighborhood in the 1950s as Trevor did later, a maquette Mayne created, in apparent hopes of doing a book, was never published. On account of the way that some of the best photographers traveled down streets that turned out to be, historically, dead ends for them, the exhibition’s over-all effect seems diluted. It is after all an exhibition by a museum of the history of London, not of photography. Many of the pictures are general views of some street or square made from a high vantage point and included merely for the subject matter rather than for photographic excellence. But it’s still worth a trip through this exhibition’s by-ways for the moments at which you’ll stumble upon a scene that is, as the photographer also recognized, something extraordinary to see.

—Colin Westerbeck

Colin Westerbeck is, with photographer Joel Meyerowitz, the co-author of Bystander, A History of Street Photography. Since the fall of 2008, Westerbeck has been Director of the California Museum of Photography at the University of California, Riverside, where Seismic Shift: Lewis, Baltz, Joe Deal and California Landscape Photography will open this fall. This exhibition with catalogue is being funded by the Getty Foundation as part of its Pacific Standard Time initiative. The exhibition, which Westerbeck is curating, will be his last for the museum as he is leaving his position there to devote himself to writing on photography. His first project will be a new edition of Bystander to be published by Phaidon Press, London, in 2013.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com