In the spring of 1963, in Birmingham, Ala., it seemed like progress was finally being made on civil rights. The notoriously violent segregationist police commissioner “Bull” Connor had lost his run-off bid for mayor, and despite Martin Luther King Jr.’s declaration that the city was the most segregated in the nation, protests were starting to be met with quiet resignation rather than uproar.

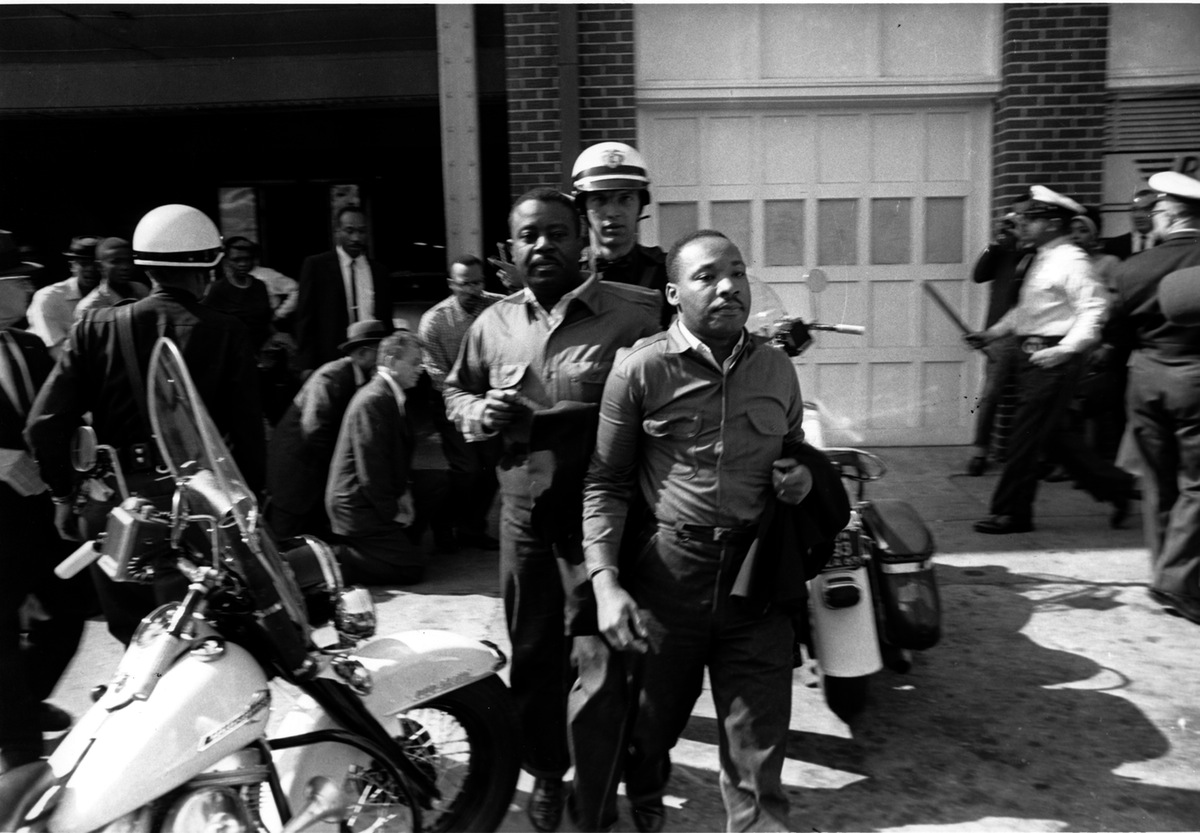

At least that’s what TIME thought: in the April 19 issue of that year, under the headline “Poorly Timed Protest,” the magazine cast King as an outsider who did not consult the city’s local activists and leaders before making demands that set back Birmingham’s progress and drew Bull Connor’s ire. “Last week Connor and Police Chief Jamie Moore got an injunction against all demonstrations from a state court,” TIME reported. “King announced that he would ignore it, led some 1,000 Negroes toward the business district. Both King and one of his top aides, the Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, were promptly thrown into jail.”

King was in jail for about a week before being released on bond, and it was clear that TIME’s editors weren’t the only group that thought he had made a misstep in Birmingham.

On the day of his arrest, a group of clergymen wrote an open letter in which they called for the community to renounce protest tactics that caused unrest in the community, to do so in court and “not in the streets.” It was that letter that prompted King to draft, on this day, April 16, the famous document known as Letter From a Birmingham Jail.

In 1967, King ended up spending another five days in jail in Birmingham, along with three others, after their appeals of their contempt convictions failed. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Walker v. City of Birmingham that they were in fact in contempt of court because they could not test the constitutionality of the injunction without going through the motions of applying for the parade permit that the city had announced they would not receive if they did apply for one. The decision prompted King to write, in a statement, that though he believed the Supreme Court decision set a dangerous precedent, he would accept the consequences willingly. “Our purpose when practicing civil disobedience is to call attention to the injustice or to an unjust law which we seek to change,” he wrote—and going to jail, and eloquently explaining why, would do just that.

Need more proof that the original letter was convincing? Though TIME dismissed the protests when they first occurred, that letter was included was included in the issue the following January in which King was named the Man of the Year for 1963. “Although in the tumble of events then and since, it never got the notice it deserved,” the magazine noted, “it may yet live as a classic expression of the Negro revolution of 1963.”

Read excerpts from the letter, which was included in Martin Luther King Jr’s Man of the Year cover story, here in the TIME Vault: Letter from a Birmingham Jail

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com