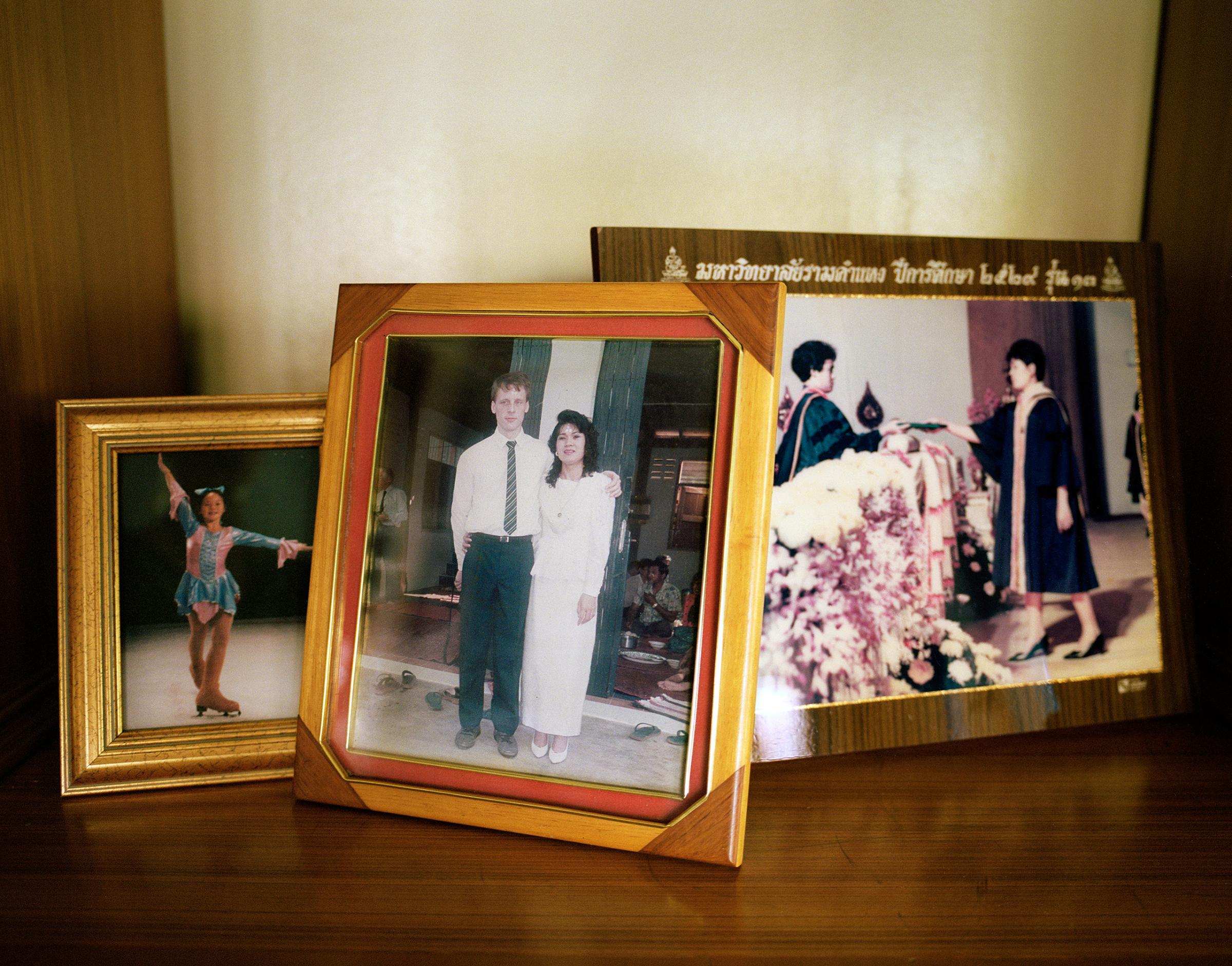

Growing up in Umeå, a remote town in northern Sweden far from the cosmopolitan capital of Stockholm, Elin Berge has always been fascinated by the idea of photographing the clash of cultures in her homeland. Her curiosity led her to build a narrative through all her projects that questions our assumptions about our relationships to foreign cultures. Her project, called Slöjor (Veils), examined the lives of young Muslim women, and now her most recent books Land of the Queens and The Kingdom, released last year, explore the phenomena of Swedish and Thai marriages.

At a time when migration is transforming Europe, Berge’s nuanced and subtle documentary style begs us to look more carefully at our own assumptions about immigration and our relationships with other cultures. The following interview via a phone call with TIME LightBox has been edited for clarity.

Paul Moakley: The Kingdom is part of a two-part project with another book titled Land of the Queens. Can you tell us the difference between the two?

Elin Berge: The Land of Queens was only photographed in Sweden. More specifically in the north part of Sweden, in the province of Västerbotten, where I live. My focus was on the Thai women in a new country. When I was done with the book, I felt there was a piece missing. I thought it would be great to have the masculine part of the story and the other country–Thailand. The projects kind of mirror each other and make a nice unit that gives both perspectives on this phenomenon.

PM: There are almost 30,000 Thai women living in Sweden. Right?

EB: The majority of those women are over 25 years old, and I can’t say for certain that every one of them came to Sweden because of a man, [but] it’s a very widespread phenomenon. The Thai women mostly come from the Isaan province in Thailand, a place that has been struggling with poverty and where the future for women might not be that easy. They [come because they] want to improve their lives.

PM: Most migrations begin with people leaving for opportunities or to escape some kind of oppression that they’re facing. What was the thing that first made you notice that this phenomenon was happening?

EB: Actually, it came to me by coincidence. It was 10 years ago when I met a Buddhist monk in an airport in Umeå, he was on his way to Fredrika, a village where he wanted to build a Buddhist temple. I started to work on a project about this temple.

In Lapland, this depopulated area with miles and miles of forest, suddenly there was a big Buddha statue placed on a mountaintop, and there were these ceremonies with Thai women dancing through the village, collecting money, singing. It was a very vivid scene. It was there that I started to notice the couples.

And then of course I knew about the stereotyped images of these couples. There are many people that think about men who go to Thailand, and they take a woman, and they go home. It’s kind of the average description of these couples, where the woman is just a victim and the man is a bad guy.

When I was in this place and I saw these women in that Buddhist context, even if it was in Sweden, I kind of got into the subject from a different angle. It made me interested in how these couples would change the places where they lived.

PM: It’s a very easy project to be judgmental about, or to make photos asking “Why are these men taking advantage of these poor women?” or “Are these women looking for money?”

EB: That’s a part of the truth. But I wanted to look beyond that. There are also so many other nuances to find. I wanted to focus on the strength of the women and the courage they must have to be able to take the risk and just leave everything behind and go with a man. I think that it’s very important when you work as a photographer to notice or admit the power that you have upon people. You’re not just keeping this inside your head, you’re making something public. I think it’s super important that you try always to find the nuances behind things.

PM: I think your work does that. It’s very gentle and subtle. The combination of your beautiful color palette, with the subject matter, plus there’s a certain distance you give your subjects. You give them space to stand back a little bit and be comfortable.

EB: I want every image to be able to have a double nature. I want that to be visible. Some people look at my work and say, “Oh you’re doing the bright side of being in a couple like this.” And that’s not my intention. I want it to be open and curious, but it’s not my intention to only paint a happy story.

PM: I also really like work that leaves a lot of room for the viewer to make up their own mind.

EB: Sometimes I feel that people get a bit frustrated about that because people think that if you’re working with documentary, you’re there to tell people how it is. I want to take pieces of the reality and put them together to make a story that makes people reflect on being a human being, thinking about the big questions like life, death and love. Making it a bit universal, maybe instead of distancing people from the subject because it’s disturbing to them.

PM: In The Kingdom, you’re focusing on the men. What are the men in these relationships facing?

EB: I think that in general, people are very judgmental about these men. In Sweden, people might think men who can’t get a woman need to go to Thailand to be able to find love. When working with The Kingdom, I was very interested in the question of masculinity.

I was wondering if it’s possible that there’s something to be found in Thailand for a man. Some kind of status. When coming to Thailand as a Westerner, you instantly become five times richer. Your money is worth more, you’re white, which is considered beautiful. Suddenly, it opens possibilities. I have seen them buy really expensive jewelry, some do plastic surgery or build really fancy houses.

I have been interested in how the men can change their masculinity when visiting Thailand. In some way it’s a possibility for the men to make a “class journey.” You can go from being just an ordinary man to a person with high status, with money, and a person to be considered important.

PM: Do you think the project provides a sense of understanding to people about these cultures coming together?

EB: I hope so. I definitely want to make people think about that and show how children are being born and how things become hybrid. I definitely see hybrids coming together and creating something new. This of course changes what’s Swedish, and what’s Thai.

Elin Berge is a photographer living is Sweden and you can find more of her work here. Her project The Kingdom is on view at the Sune Jonsson’s Center for Documentary Photography. The Kingdom includes a soundtrack written and performed by Frida Hyvönen.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @paulmoakley.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com