Sen. Rand Paul announced a run for the White House Tuesday, armed with a message he said was “loud and clear and does not mince words: We have come to take our country back.”

Paul’s speech nodded at his younger fans, as well as making a pitch as a presidential candidate for limited government and fiscal conservatism. A campaign video released Monday had set up the Kentucky Senator as the one man who can “defeat the Washington machine and unleash the American dream.” The words linger atop a silhouette of the candidate as supporters chant “President Paul.”

Forgive Paul for going generic with his slogan; there are only so many active verbs and available bromides left in our shared campaign storage unit. But the choice is emblematic of a larger branding decision that could help shape the fate of his presidential bid. Paul rose through the ranks by promising to change the Republican Party, but on the cusp of his campaign he has tweaked his own positions to fit within the GOP.

Ever since his 2013 filibuster against Barack Obama’s drone policy vaulted him from Tea Party curiosity to the forefront of the GOP, Paul has boasted a clearer rationale for a presidential bid than any of his rivals. He has been telling audiences that a party staring down the barrel of demographic change must become bigger, broader and more inclusive to win back the White House. His campaign is predicated on the promise that he can attract a younger, more diverse coalition of voters through issues ranging from a more restrained foreign policy to criminal-justice reforms to reining in domestic spying.

The pitch has made Paul a powerful player in the GOP presidential field. He is running at or near the top of the polls, with a stocked bank account and a political network wired through key early states. Instead of downplaying expectations, Paul prefers to stoke the hype. “Nobody is running better against Hillary Clinton than myself,” he told Fox News.

“The path to the nomination is virtually set up for us,” says Doug Wead, a friend and adviser to Paul who notes the senator’s organizational strength and ideological appeal in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada. “It’s within the realm of possibility that we could have three sequential wins” out of the gate.

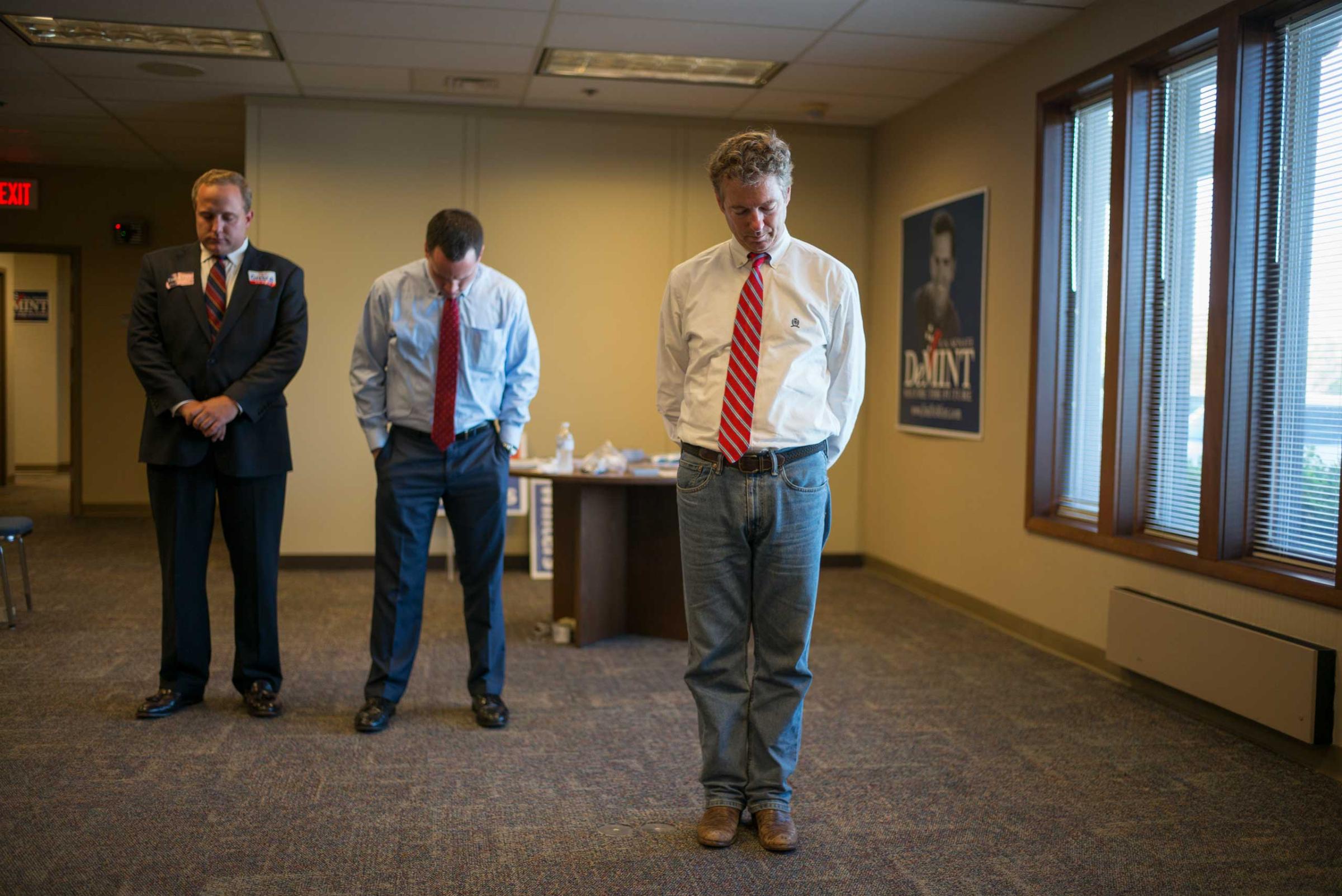

Photos: On the Road with Rand Paul

But even as he claims frontrunner status, there’s a question of whether the Kentucky senator has missed his ideological moment. Paul’s rise in the polls over the past two years came as the Republican Party warmed to the merits of Paul’s non-interventionist foreign policy after more than a decade of war. In one June 2014 survey, 53% of Republicans said the U.S. should “mind its own business” abroad, up from just 22% in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Yet in recent months, as the U.S. ramped up nuclear negotiations that would ease sanctions on Iran and the Islamic State released a series of ghastly beheading videos, the GOP has rediscovered its hawkish impulses. A Quinnipiac poll last month found that 73% of Republicans now support sending ground troops to battle ISIS in Iraq and Syria.

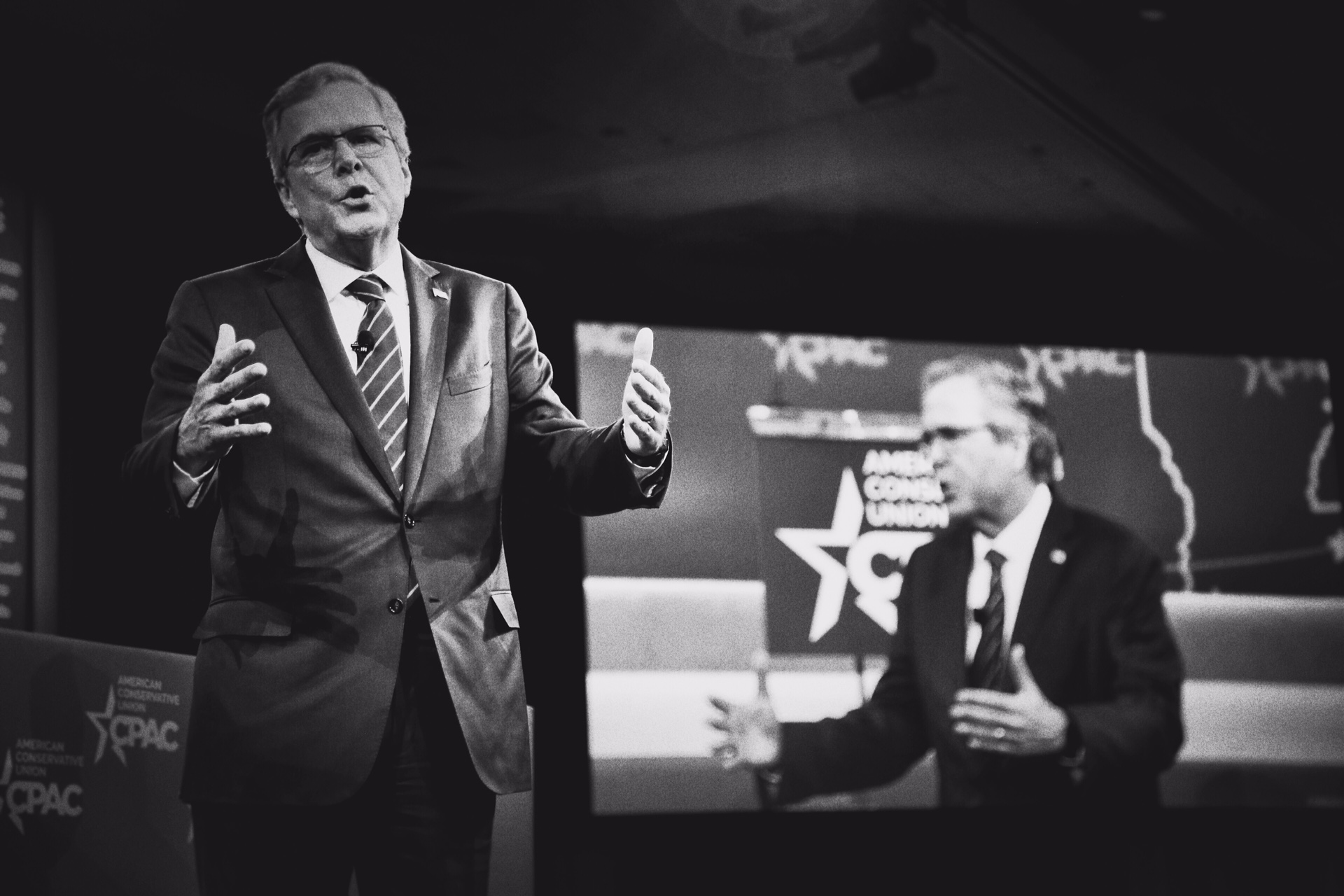

Paul has reacted to the Republican regression on foreign policy with an apparent evolution of his own. Lately he’s shelved his signature non-interventionism in favor of more conventionally muscular rhetoric. When it comes to federal spending, he told the Conservative Political Action Conference in February, “for me, the priority is always national defense.” A few weeks later, he introduced an amendment calling for a $190 billion boost to the defense budget—a head-snapping reversal from his 2011 proposal to cut defense spending and reduce war funding from $159 billion to zero.

Paul supporters say the shift is a function of changing conditions in the Middle East, not a strategic repositioning. (His campaign spokesman did not return a request for comment for this story.) In any event, it may do little to assuage GOP hawks, who remain deeply leery of Paul. Meanwhile, it may may complicate matters on another front. To win the primary contest, Paul has to pull off a delicate balancing act: expand his political coalition without alienating the demanding libertarian supporters inherited from his father. Ron Paul’s presidential campaign was derided by the political class as more farce than force, but to fans he was a beacon of clarity. His son risks irking the libertarian faithful by softening his stances to suit the political climate.

Foreign policy isn’t the only realm where Paul has modulated his message. He has long argued the federal government should let states decide the question of gay marriage. “The Republican Party,” he told CNN, “can have people on both sides of the issue.” Now he is telling socially conservative audiences that gay marriage is a “moral crisis” which “offends myself and a lot of other people.”

This kind of talk may help Paul with Evangelicals in Iowa. But it won’t win over the young voters or independents he often brags about bringing into the GOP fold. Nor is there much proof that the bridge-building he’s done with communities of color will translate into votes. And on issues where Paul’s positions once stood out, such as criminal-justice reform or drug policy, some of his Republican competitors have since caught up.

What’s left if Paul sands down his edges? Perhaps a relatively conventional Republican candidate. Paul’s campaign calls him “a different kind of Republican,” but the issues he emphasizes in his debut video are standard GOP fare, from term limits to a balanced budget to jabs at Congress and the failures of liberalism. His political operation is a vast and motley assemblage, with top staffers who worked for the likes of Rick Santorum and George W. Bush. A man who made his name inveighing against foreign misadventures will campaign in South Carolina this week atop a World War II-era aircraft carrier, a totem of American military might. He is running against Washington from a perch in the Senate, using testimonials from D.C. talking heads to argue he is different.

Paul has undertaken the ambitious project of selling a hidebound party on the merits of reinvention. And if it may seem to some as though he has reinvented himself in the process, supporters say the occasional shift in tone is just part of the larger deal.

“The overriding goal for Rand Paul is to make government smaller,” says David Adams, his former Senate campaign manager. “Anything that needs to be tweaked or massaged or polished to get from here to there is fair game. He will come under a lot of criticism for saying things that sound different from what he may have said at another time, but he has consistently and persistently moved toward making government smaller and winning the ultimate battle.”

Read next: What Happened When Rand Paul First Got Into Politics

Listen to the most important stories of the day.

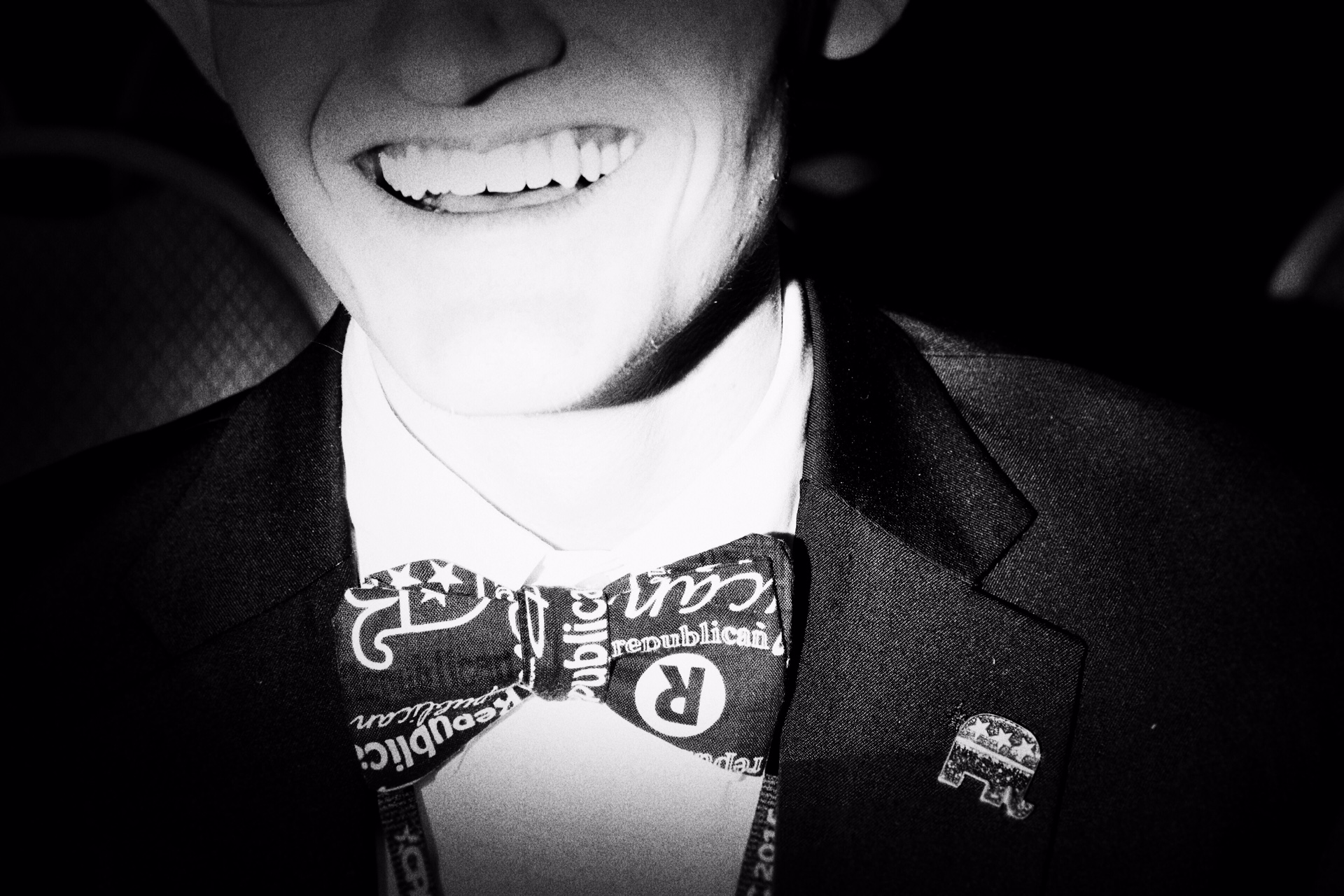

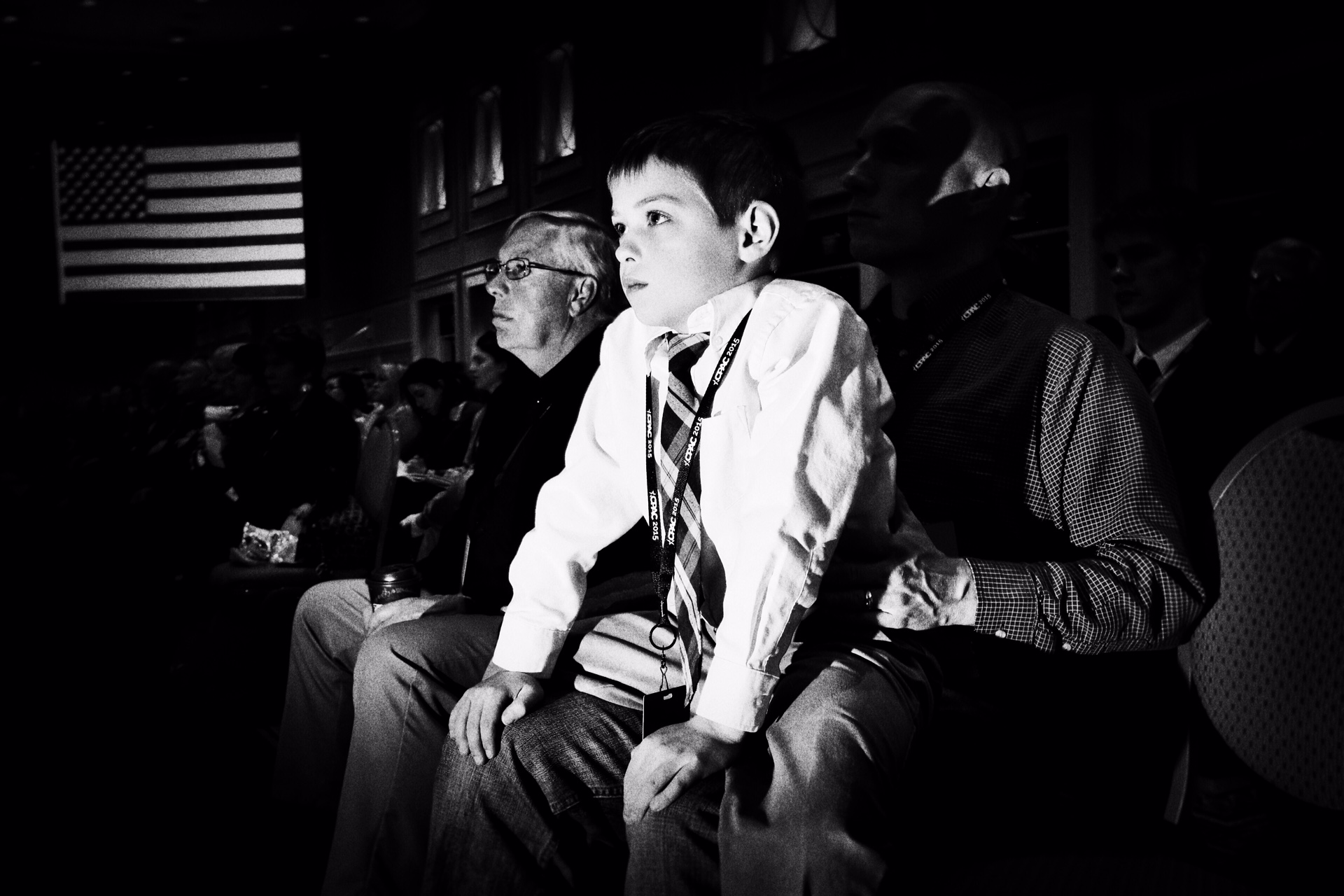

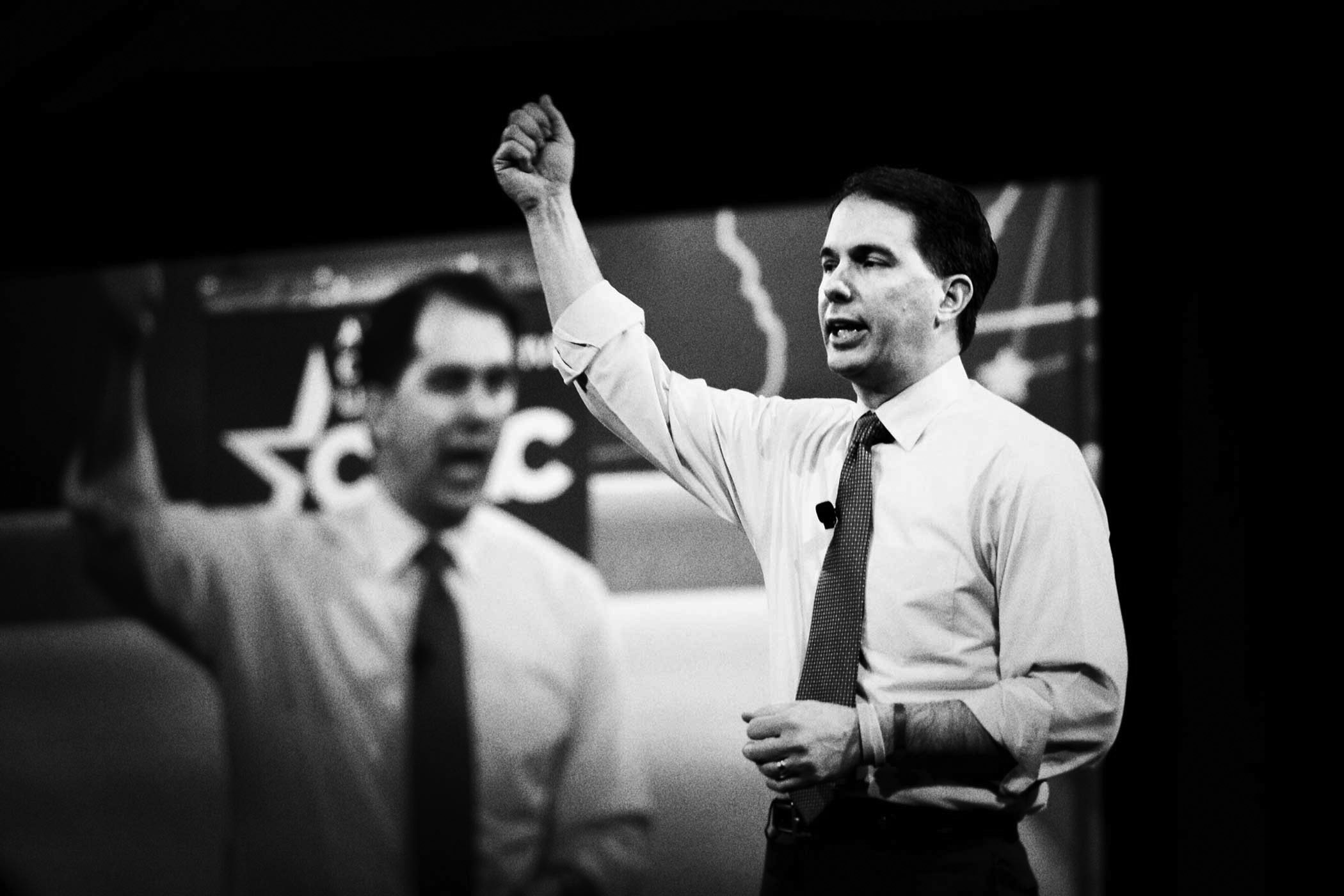

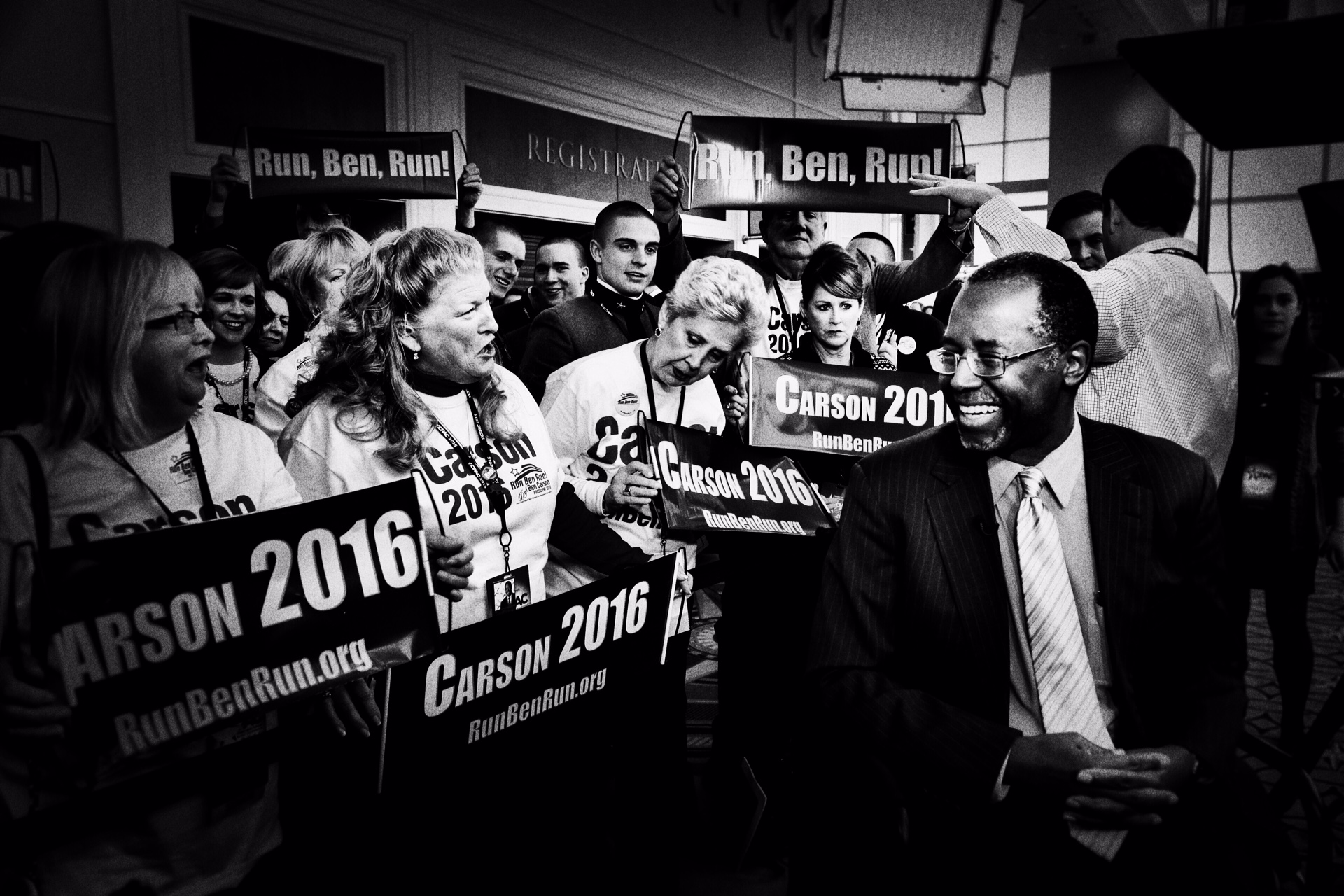

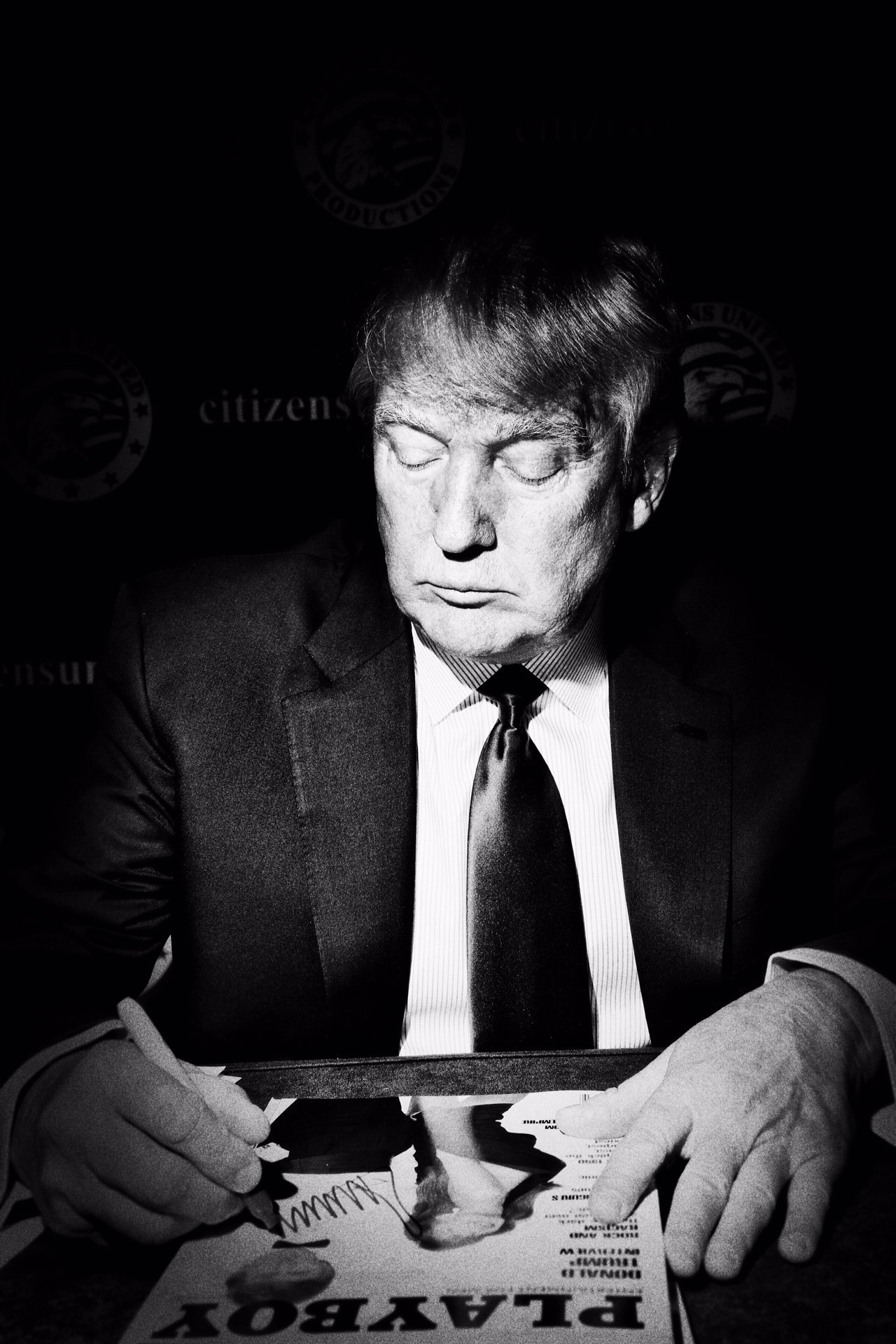

Behind the Scenes of CPAC

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com