Georgetown is a city of 54,000 just north of Austin known for beautiful Victorian-era architecture around our historic courthouse square. Founded in 1848, we are home to Southwestern University, a small liberal arts college.

The City of Georgetown recently announced that our municipal electric utility will move to 100 percent renewable energy sources by 2017. That probably caught some folks by surprise. A town in the middle of a state that recently sported oil derricks on its license plates may not be where you’d expect to see leaders move to clean solar and wind generation.

No, environmental zealots have not taken over our city council, and we’re not trying to make a statement about fracking or climate change. Our move to wind and solar is chiefly a business decision based on cost and price stability.

The city’s contracts for solar and wind power will provide wholesale electricity at a lower price than our previous contracts. These long-term agreements also provide a fixed cost that will enable the city to avoid the price volatility and regulatory costs we were likely to have seen had we continued to use electricity generated by burning fossil fuels. With energy costs locked in for the long-term, we can maintain competitive, predictable electric rates through 2041.

The city’s shift to renewables also was the result of factors related to our previous wholesale power contracts, the Texas electric grid, and timing.

Our municipally-owned electric utility, started in 1911, has used power supply contracts to provide electricity to our customers since we shuttered our city power plant in 1945. Ending a long-term wholesale power contract in 2012 left us free to seek new power suppliers.

Meanwhile, Texas has become a leader in wind generation. When wind turbines began to sprout in West Texas and the Panhandle in the 1990s, the state faced bottlenecks in transmitting that energy where it was needed, to the growing metro areas of Austin, Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio.

The Texas legislature and Public Utility Commission eased the bottlenecks with the construction of 3,600 miles of transmission lines at a cost of nearly $7 billion. Now wind farms in West Texas and the Panhandle can move energy to the state’s population centers.

That new transmission capacity and new renewable projects were in place when Georgetown sought bids for power suppliers in 2013. We signed a contract last year for energy from the Spinning Spur 3 wind farm 50 miles west of Amarillo. That project is currently under construction and will begin sending us power in January of 2016. Spinning Spur 3 will meet most of our current demand throughout the day, with the exception of the peak demand periods, especially in the summer.

Because Georgetown is in the fastest-growing large metro area in the U.S., we needed more capacity to meet projected growth. Due in part to a drop in price on photovoltaic solar panels, last year we received a low-cost bid on solar power, and this February we signed a contract to purchase power from a solar farm in west Texas that is currently under construction. That power will be online by 2017.

Using solar power in the daytime peak and wind power throughout the day matches our power supplies with local demand patterns. The solar power produced in West Texas will provide a daily afternoon supply peak that mirrors our demand peak in Georgetown, especially during the hot summer months. Wind power production in the Panhandle exists throughout the day and is highest in the evening or early-morning hours. This means that wind power can most often fill power demand when the sun isn’t shining.

We have been asked what happens if the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine out west. Will the lights go out? Given the wind profile of the Panhandle, the radiance rating for West Texas, and the amount of energy we have under contract, we know that our wind and solar farms will be able to provide our power throughout the day. If both resources were not producing simultaneously — an unlikely event — the lights would stay on because the Texas grid operator, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, will ensure generation is available to meet demand. In the short term, our solar and wind farms will provide more overall energy than we need. This means we will be able to sell extra solar and wind power we don’t use, providing an overall benefit to power users in the state.

Another reason solar and wind energy makes sense relates to water. Drought conditions and half-empty reservoirs have been common in Texas in recent years. Traditional power plants making steam from burning fossil fuels can use large amounts of water each day. Our move to renewable power is a significant reduction in our total water use in Georgetown.

One of the most important benefits of being 100 percent renewable is the potential for economic development. Many companies, especially those in the high-tech sector, are looking to increase green sources of power for both office and manufacturing facilities. Our 100 percent renewable energy can help those companies to achieve sustainability goals at a competitive price without the burden of managing power supply contracts.

Georgetown may not be run by environmental activists, but our residents do want us help them raise their families and run their businesses in a manner that is cost-effective and sustainable. We hope other cities follow our lead. So don’t be surprised if at some point down the road you see Texas license plates emblazoned with solar panels and wind turbines.

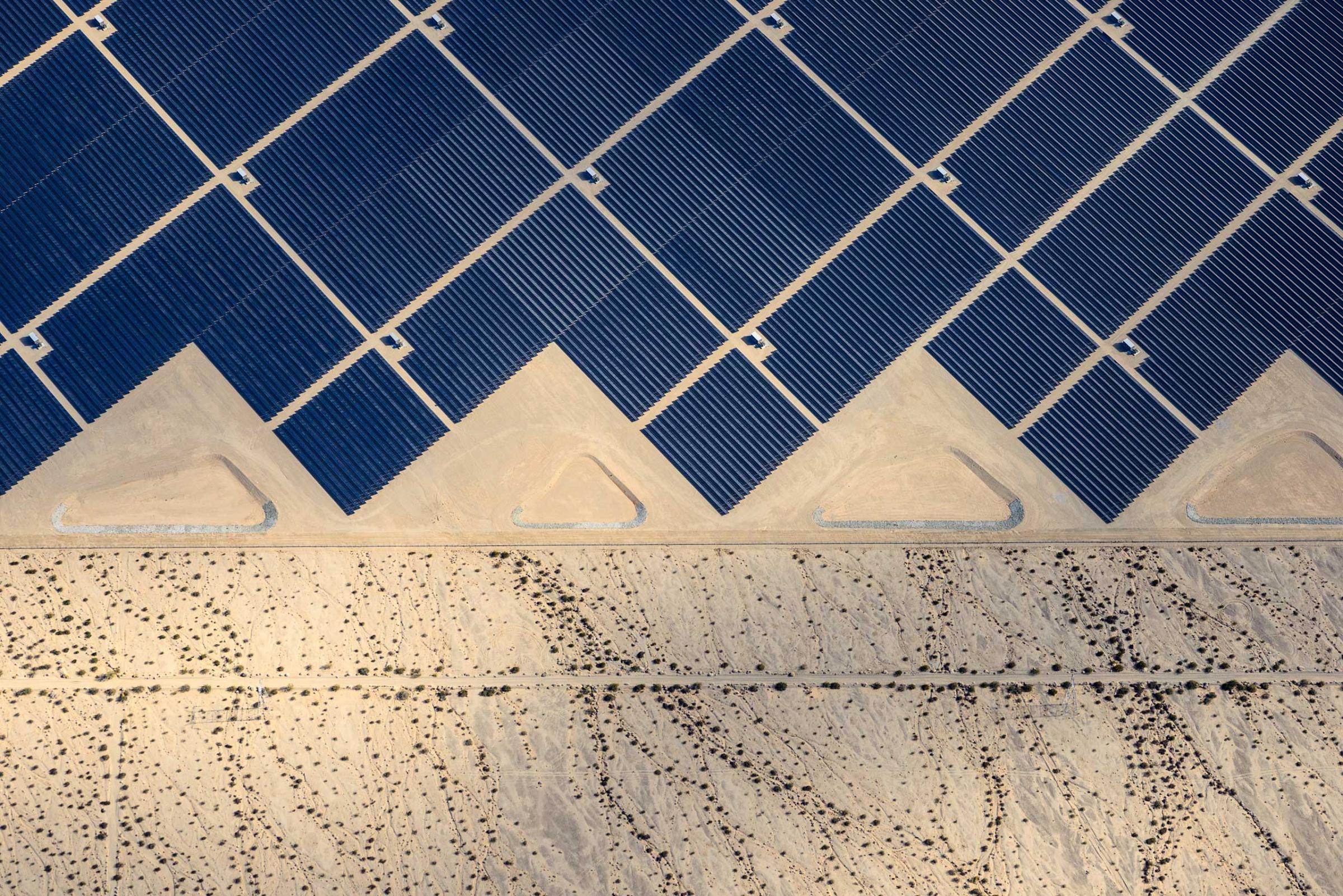

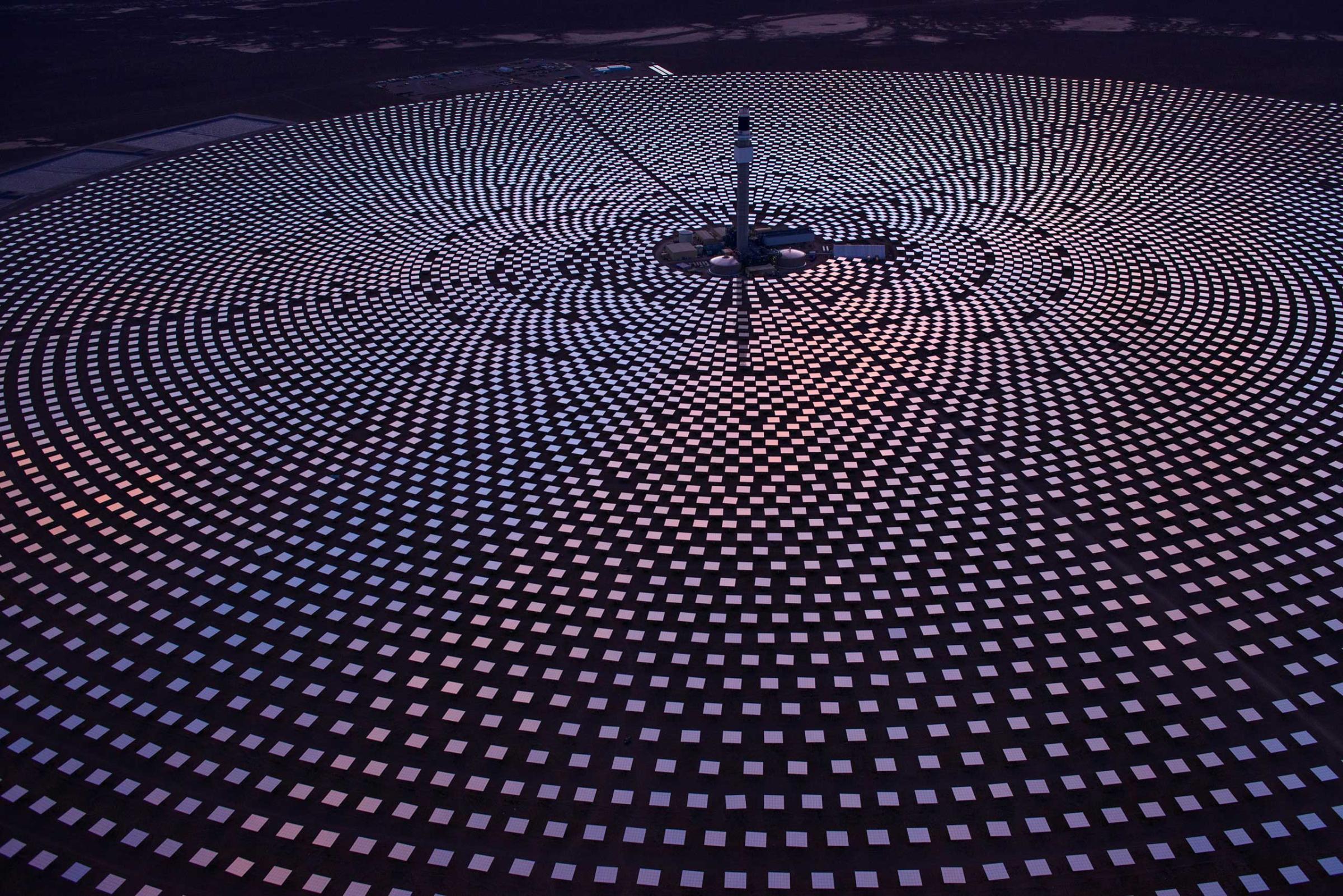

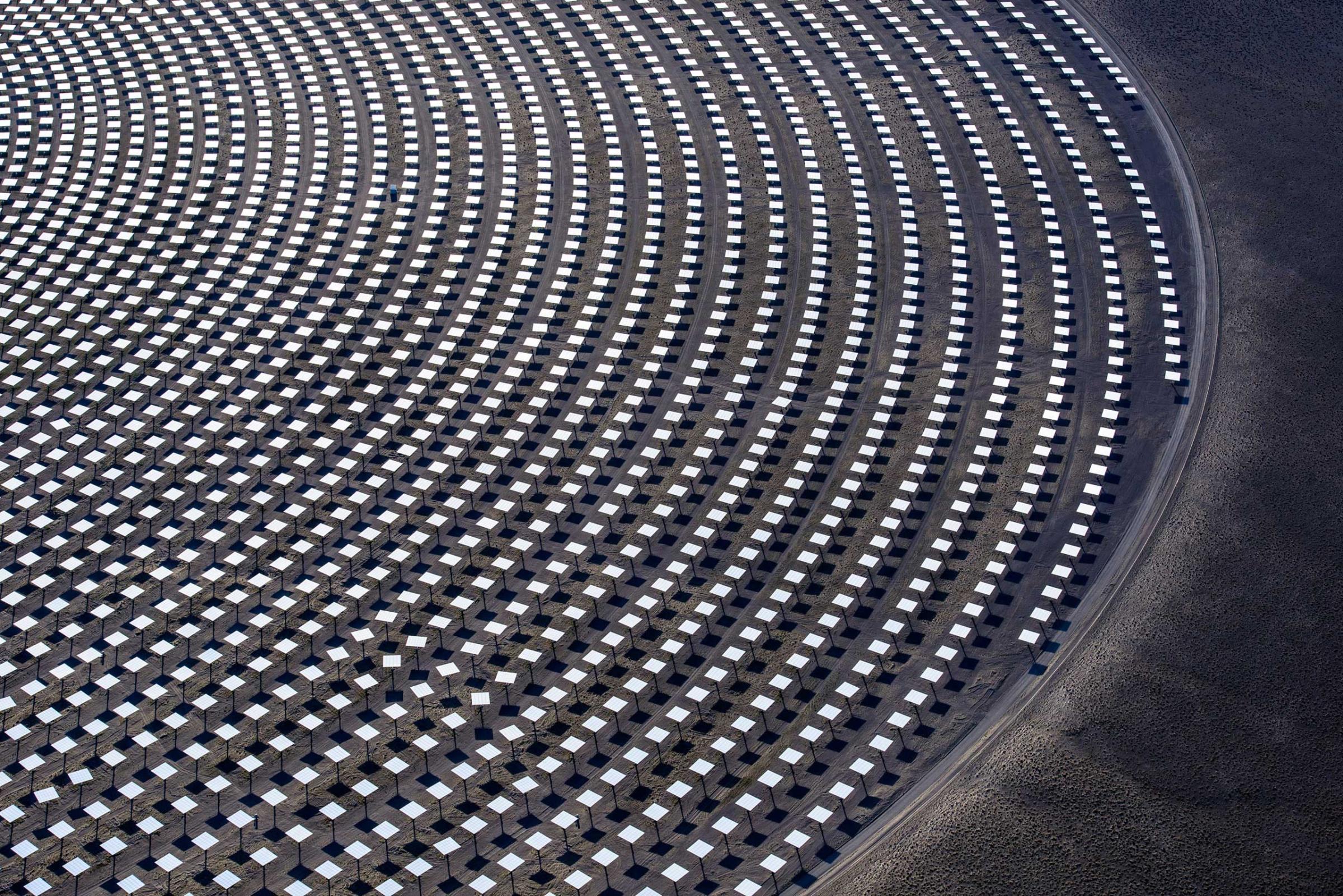

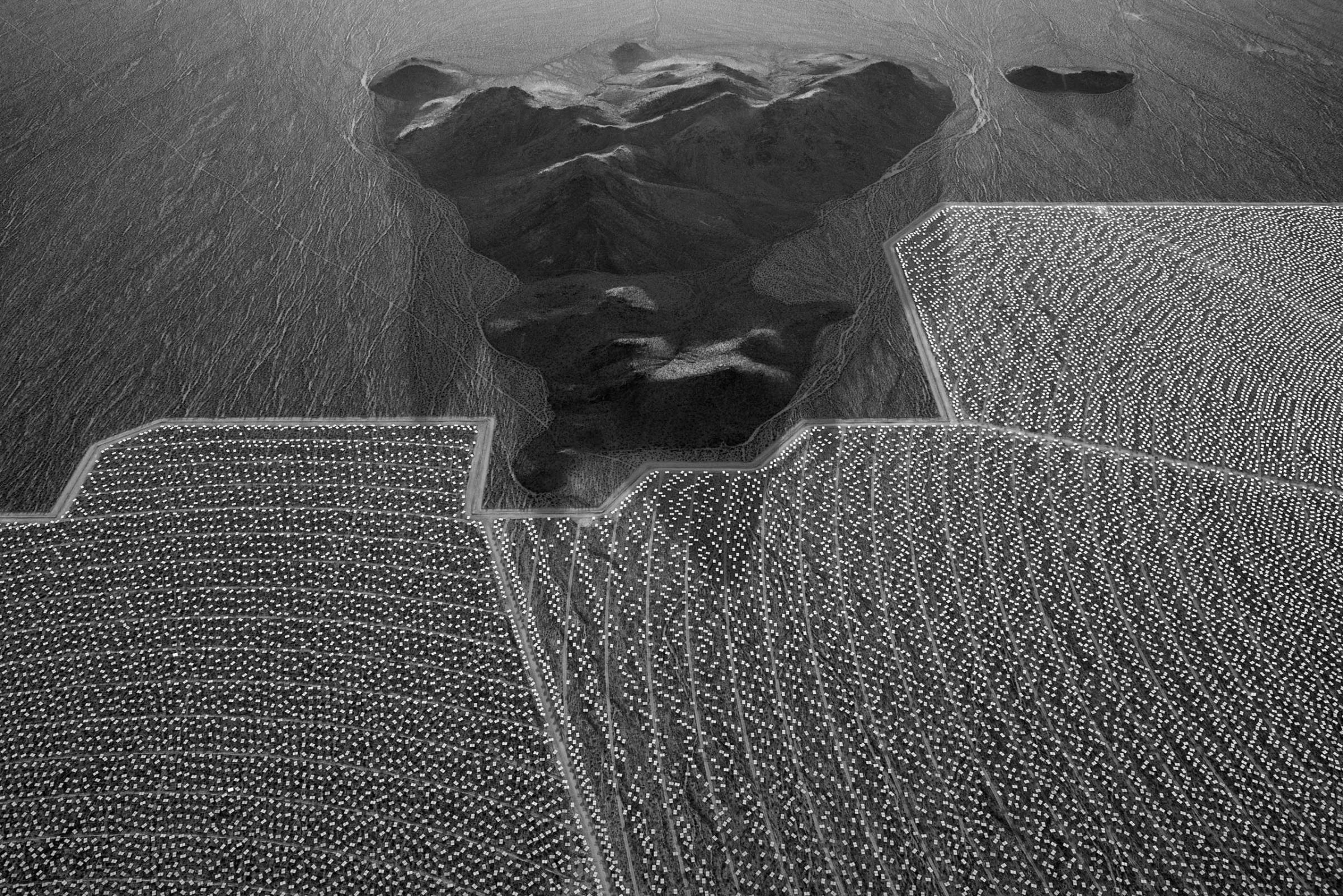

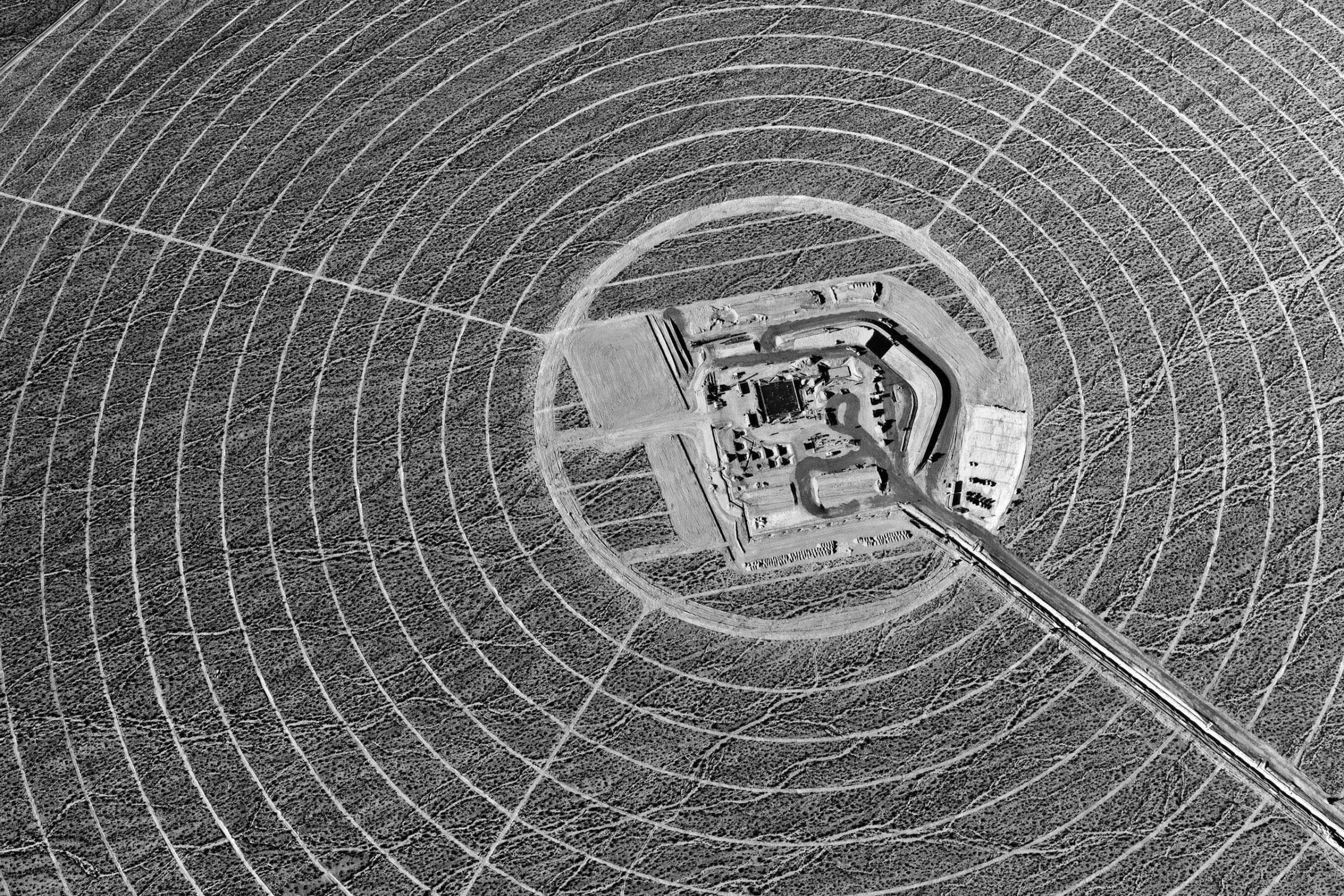

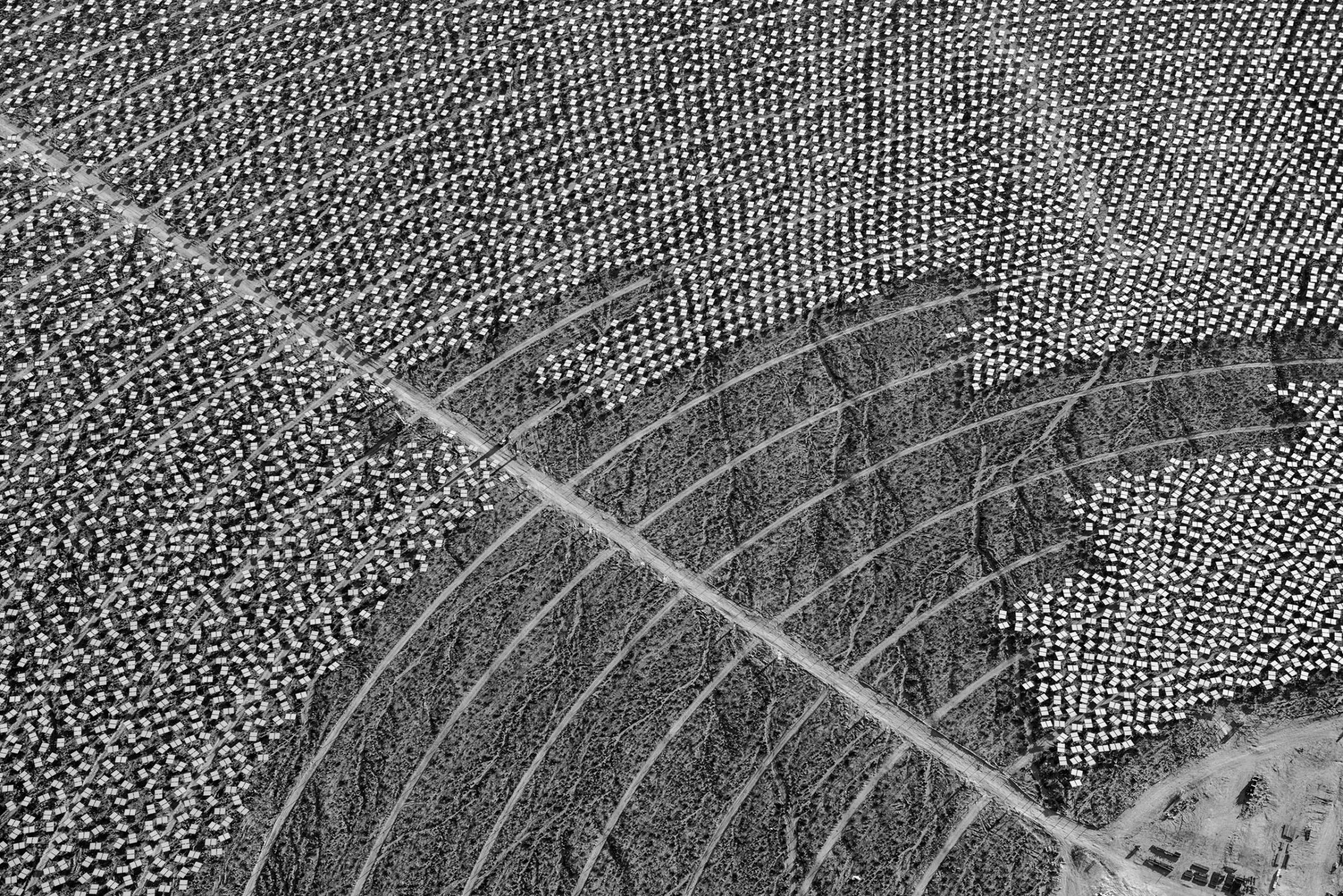

See the World's Largest Solar Plants From Above

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com