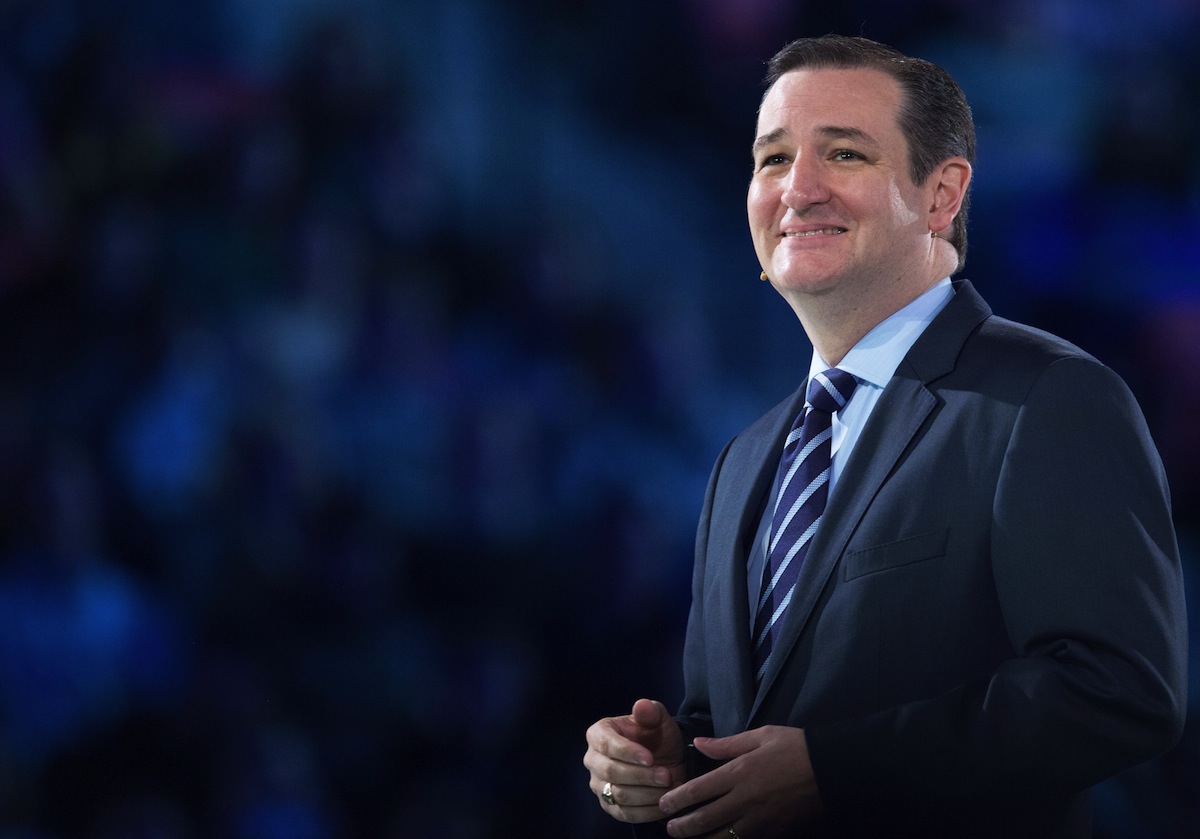

Texas Sen. Ted Cruz says he no longer listens to classic rock, but he still found a way to channel the lyrics of John Lennon when he launched his presidential campaign. “Imagine,” he told students at Virginia’s Liberty University on March 23, repeating the refrain 38 times in a half-hour stem winder that felt less like a campaign speech than a guided tour of a conservative Valhalla.

The dreamy slogan may have seemed out of whack for the firebrand politician. But in some ways Cruz was just following the lead of an independent group that hopes to make him President.

Weeks before Cruz climbed onstage, the Stand for Principle PAC printed and passed out T-shirts and placards that read “Imagine Ted Cruz as President.” The group’s organizer, Maria Strollo Zack, says helping Cruz promote his message is just the start. Zack wants to raise as much as $50 million—perhaps more than the campaign—to pay for anything from television ads to grassroots outreach. “We’re rewriting the book on how super PACs can be leveraged,” she says.

So are Cruz’s rivals. Likely candidates such as Jeb Bush and Scott Walker have been deeply involved in setting up their outside-spending vehicles, installing top staff and drawing down funds to pay for early voter contact, including trips to primary states. Such efforts are the latest way to game the traditional campaign-finance system, which limits the amount of money individuals can give to candidates and forbids direct donations from corporations. The Cruz super PAC, for instance, is barred from directly coordinating campaign spending or strategy with Cruz, but it is able to raise and spend unlimited sums on the candidate’s behalf while collecting money from just about anyone.

In 2012 super PACs were used as blunt instruments of destruction: the group backing Mitt Romney devoted about 90% of the $142 million it spent overall to TV attack ads. But in the 2016 presidential race, these organizations are poised to play a much bigger role, taking over more-traditional campaign duties ranging from field organizing and voter turnout to direct mail and digital microtargeting. “They are becoming de facto campaigns,” says Fred Davis, a Republican media consultant who ran former Utah governor Jon Huntsman’s presidential super PAC in 2012.

Campaign-finance watchdogs say that super PACs, which were created in the wake of two 2010 court rulings, undermine spending limits that have governed elections for generations and allow high-dollar donors to amass influence that Congress has long sought to prevent. The new crop of super PACs are now pushing boundaries in ways that were unimaginable just five years ago. “The sky’s the limit.” says Carl Forti, a GOP strategist who co-founded the Romney super PAC in 2012.

Many Republican hopefuls have delayed their official campaign announcements so they can spend more time and energy seeding their outside groups. Bush, the former Florida governor, has been dropping in on donors’ conclaves across the Republican Party’s wealthiest precincts, soliciting massive checks for his Right to Rise super PAC. Mike Murphy, Bush’s longtime senior adviser, is expected to stay at the super PAC to orchestrate its strategy rather than migrate to the campaign.

Walker’s high-dollar outside group, Our American Revival, is run by the Wisconsin governor’s future campaign manager, Rick Wiley, who—like Walker’s spokesperson, senior political advisers and key field staff in states like Iowa and New Hampshire—is drawing a salary from the organization until the formal campaign kicks off. Former New York governor George Pataki charged up to $250,000 per head at a fundraiser for his group, We the People Not Washington, which features a form on its website for supporters to request a meeting with Pataki. And as Hillary Clinton marches toward a likely campaign launch, her super-PAC supporters at Ready for Hillary are laying the groundwork by adding to their email rolls and signing up a flurry of new members for the group’s finance council.

Much of this activity exploits a legal loophole. “What’s unique,” says Anthony Corrado, chairman of the board of trustees at the nonpartisan Campaign Finance Institute, “is candidates becoming associated with a super PAC before embarking on a campaign.” Building early receptacles for large checks may also limit the amount of time candidates are forced to spend raising money later on.

As the balance of power shifts toward super PACs, the strategists running them are studying the ways outside committees can be more than just attack machines once the campaigns take flight. “Every super PAC will have to decide what their mission should be and how they want to game plan,” says Austin Barbour, who will run former Texas governor Rick Perry’s super PAC if Perry jumps into the race. “But we’re in a post-TV age.” Super PACs will take on a variety of new tasks over the next year, from grassroots organizing and micro-targeting to digital operations. “Those will all be a part of any well-run super PAC this cycle,” predicts a GOP strategist running another likely presidential candidate’s outside group.

The question no one has an answer for yet is how a super PAC’s time and money can dovetail with the campaign’s efforts instead of duplicating them. Since such groups are barred from coordinating strategy with campaigns after the candidates declare, they may struggle to run complementary data or field operations. But campaign-finance watchdogs worry the rules will be flouted because there’s nobody to enforce them. “It’s open season,” says Fred Wertheimer, president of Democracy 21, who notes that three of the six members of the Federal Election Commission—the agency in charge of overseeing political spending—view money as a form of speech and are ideologically opposed to reining it in. And while the Department of Justice can prosecute violations of campaign-finance law, experts predict they will be wary of doing so except in extreme cases.

Candidates will be able to send strategic cues in public statements that super PACs can pick up on. But campaign strategists say the anything-goes legal landscape could ultimately cause problems for the indiscreet. “Someone’s going to get popped,” one predicts. “The question is who and when.”

After his speech at Liberty, Cruz began a fundraising tour that would whisk him to meetings with New York financiers, Texas investors and other executives. Within 36 hours, he said he had raised more than $1 million for his actual campaign. The cash infusion was overdue: Cruz’s coffers are already dwarfed by those of rivals like Bush. As a federal officeholder, Cruz hasn’t had the same freedom to work with his super PAC.

But the outside group will be there to help him with his stated strategy—to win the nomination by mustering a grassroots army that mixes the Tea Party faithful with the social conservatives who dominate the first-in-the-nation Iowa caucuses. And at the head of the brigade is an old pal: Cruz’s college roommate and debate partner David Panton, a Jamaican-born Atlanta private-equity executive who cut the super PAC its first $100,000 check last November. “I think he should be President,” Panton says. “It requires a lot of money to run a presidential campaign.”

Zack says the Senator can live on less cash than his rivals but insists that support will be there when he needs it. After all, Stand for Principle can get Cruz himself to juice fundraising by appearing at its events, as long as he does not ask for the money directly. Just imagine the possibilities.

—With reporting by Zeke J. Miller and Michael Scherer/Washington

Read next: 3 Things Ted Cruz Could Learn From Taylor Swift

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com