No one kept a secret like the old Soviet space program kept a secret. Back in the early days of the space race, Sergei Korolev, the Soviets’ chief designer, was known only as, well, the Chief Designer, the better to prevent any assassination attempts that officials from Roscosmos—the Russian NASA—convinced themselves the Americans were cooking up. Baikonur, the Russian Cape Canaveral, hidden away in the Kazakh steppes, stole its name from a mining town 200 miles north, the better to confuse enemies who might come looking for it.

MORE: Watch the Trailer for TIME’s Unprecedented New Series: A Year In Space

But the secrecy of Baikonur was partly just geography. If you want to get to space you need launch pads that aim away from populated areas and that are located as close to the equator as possible, giving your rockets a boost in speed thanks to the physics of Earth’s rotation. In the U.S. that meant Florida, with millions of people to the west and north but no one at all in the ocean to the east. In Russia, that meant Baikonur.

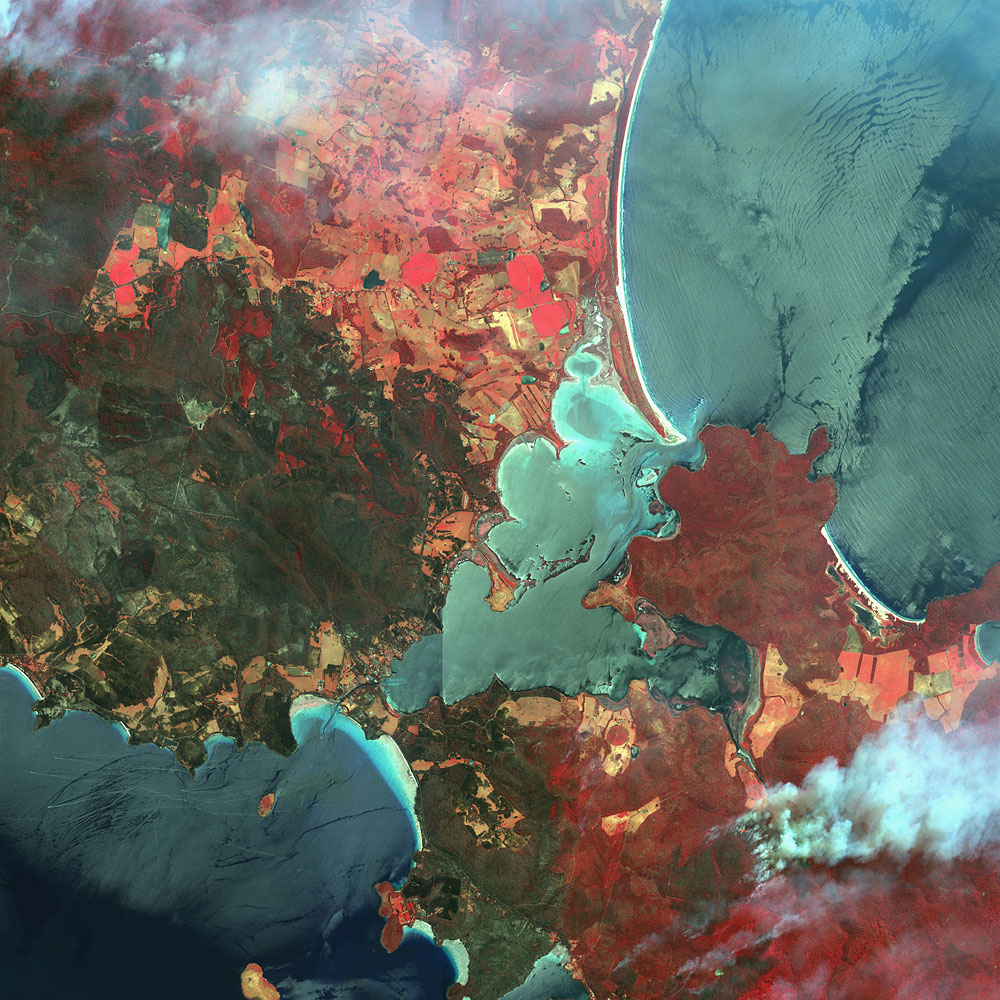

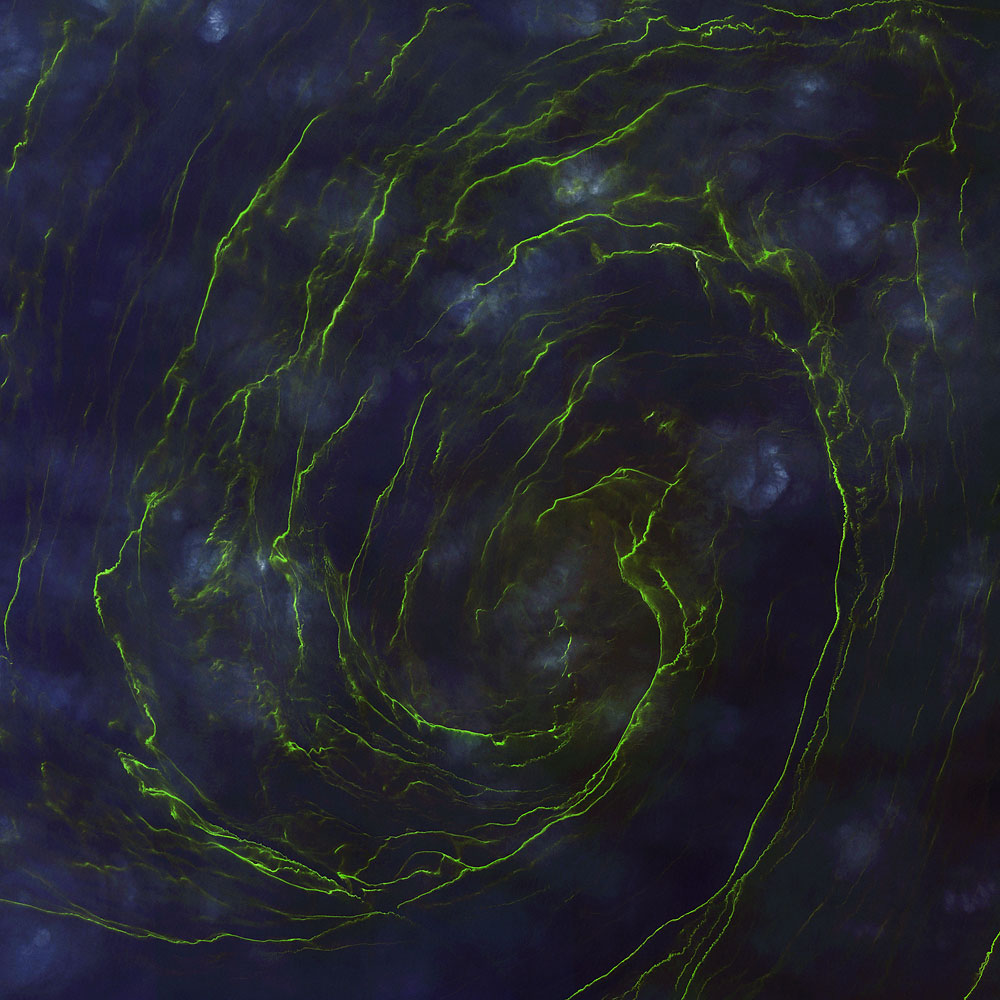

PHOTOS: 20 Breathtaking Images of Earth From Space

![{

bandList =

[

4;

3;

2;

]

} Colorado River](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/colorado.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

The Baikonur launch facility—where cosmonauts Mikhail Kornienko and Gennady Padalka and astronaut Scott Kelly will lift off for the International Space Station on March 28, with Kelly and Kornienko slated to stay a full year—is a half hour drive into the desert outside of Baikonur proper, which is itself is at least three hours away from pretty much anything at all. The old spaceport, when you finally arrive, looks exactly like you would have expected it to look if you grew up during the cold war when everything Soviet was synonymous with scary.

MORE Meet the Twins Unlocking the Secrets of Space

There are the cement blockhouses and the skeletal gantries and the security fences everywhere, all growing out of the surrounding scrub without so much as a single sapling or tuft of grass to add a little green. You could photograph the place in color, but why bother?

But inside Baikonur, none of that matters. Here, the sense of place—or placelessness, really—falls away, replaced by the same kind of closed-world, finely focused, center-of-the-universe bustle that accompanies any launch facility anywhere on the planet.

On Monday, at T-minus five days, the three members of the prime crew and the three members of the backup crew were scheduled to run their final ingress drills, climbing into their Soyuz spacecraft, for the first time—or at least the first official time. That, according to more than half a century of custom, required an equally official handoff, in which the people who built the spacecraft would, in effect, turn the keys over to the people who would drive it.

The ceremony took place in a large meeting room divided by a glass partition. Representatives from NASA, Roscosmos and the media crowded on one side of the glass and waited until officials from both Roscosmos and Energiya, the state-owned contractor that built the rocket and the spacecraft, entered and sat at a conference table facing the partition. The cosmonauts and astronauts, now in preflight medical quarantine, entered through a door on the other side, and sat at a matching conference table facing the officials.

The spacecraft is now ready for you, one of the government men said to the crew in Russian. It is ready or flight.

The astronauts and cosmonauts nodded their thanks.

Are you ready to go to work?

We are, answered Pedalka, the commander.

A few more words of good wishes and congratulations followed, and then the officials rose, which was the cue for the crew to rise. The little ceremony, weeks in the planning and minutes in the execution, was over.

The crews moved to a massive hangar adjacent to the conference room, where multiple spacecraft sit in different stages of flight-readiness. Near the back of the hangar are three unmanned Progress ships, built to carry supplies and cargo to space. Nearby is a Soyuz that will fly later this year, a beautifully ugly, three-pod machine that is nowhere near ready for its launch and still sits with its cables and lines and guts exposed.

And at the front of the room is Kelly’s, Kornienko’s and Padalka’s Soyuz, this one hidden inside its sleek, white, 22-ft. (6.7 m) third-stage shell, looking like a proper rocket should look—though still not mated to the second and third stages which will add 155 additional feet (47 m). Caging the third stage is a yellow scaffolding that rises close to the hangar’s ceiling. On the wall, overlooking it all, is a massive blue on white painting of Korolev—the father of everything that is happening here and everything that has happened since the 1950s.

The back-up crew climbs the scaffold and enters the cockpit first, spending 30 or 40 minutes there, getting the feel for the spacecraft that, should circumstance warrant, one or more of them could be flying at the end of the week. The prime crew follows.

For Kelly, and for his American back-up Jeff Williams, Baikonur is the right place to be spending the last few days on Earth before taking off for a year’s worth of days in space. “It’s very different from home,” Kelly says, “very different from what I’m used to. It’s a good way to separate myself slowly from what’s familiar.”

The separation will get a bit harder before it gets easier. Later in the week, his daughters—ages 20 and 12—his girlfriend and his father will arrive in Baikonur for the launch. For his father especially, the experience will be wearing. This is Kelly’s fourth flight, matching the four his twin brother Mark, a retired astronaut, has already flown.

“No parent of an astronaut has watched eight launches,” says Kelly. “He’ll hold the record.”

This probably, but not definitely, will be the last one the senior Kelly will have to bear. Scott is likely to retire after his year aloft , but space gets deep into an astronaut’s bones. There are few—perhaps none—who’ve flown who haven’t sorely missed the experience when it’s over. Kelly, for all anyone can say, could return. For those who do, Baikonur—ugly and functional and wonderful as the Soyuz itself—will remain the gateway back.

Read next: Maybe We Really Are Alone In the Universe

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger / Baikonur, Kazakhstan at jeffrey.kluger@time.com