I’ll bet Chuck Bednarik sneered at the glitzy name the National Football League pinned on its championship game in 1967: the Super Bowl. To Bednarik, the Philadelphia Eagles star from 1949 to 1962, a football game was not a piece of crockery deigned by Andy Warhol. It was trench warfare every Sunday afternoon, in the Iron Age of professional football. And Bednarik, who died Saturday at 89 in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, was the NFL’s Iron Man.

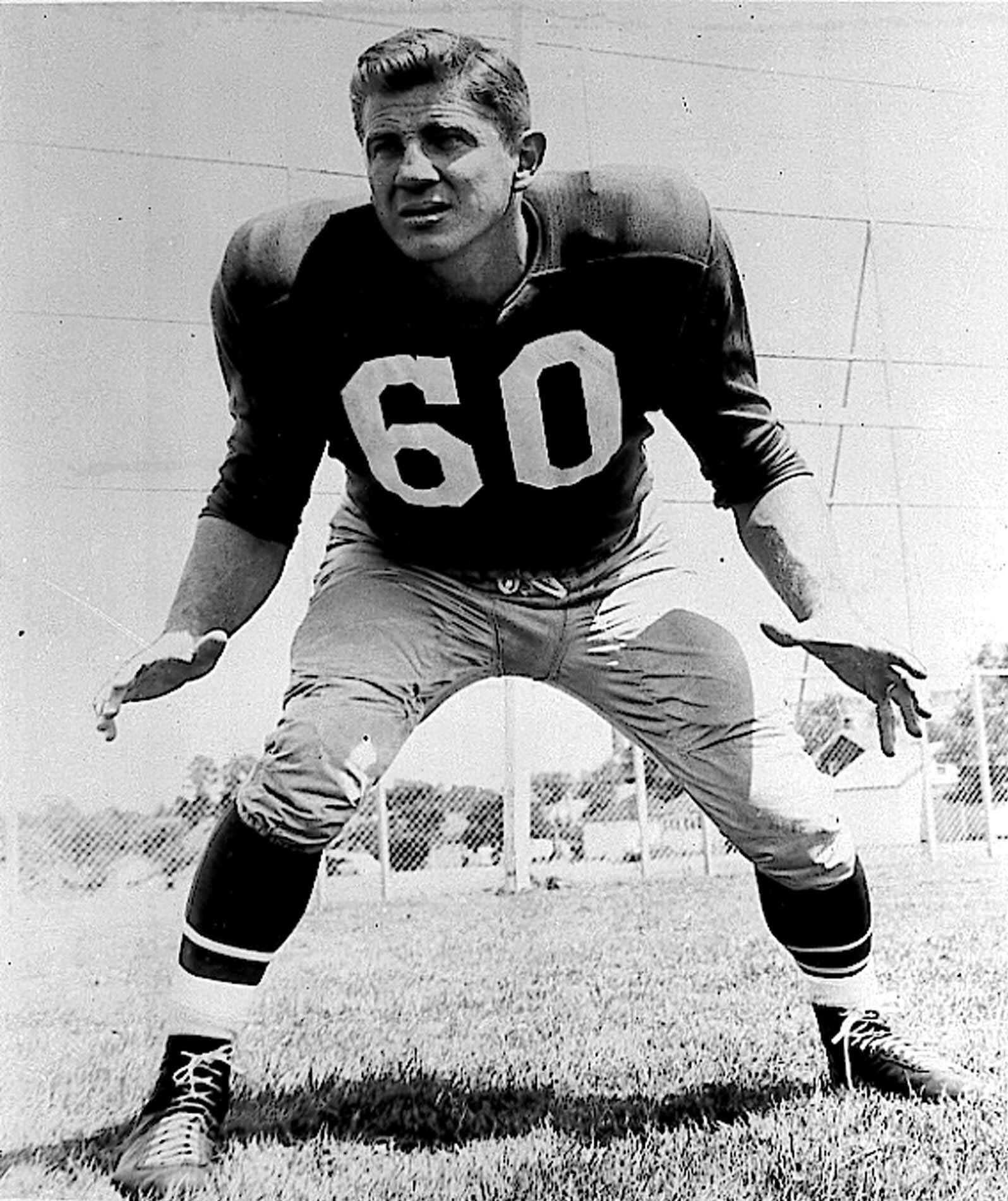

No. 60 was also the 60-Minute Man, often playing both offense (center) and defense (linebacker) for an entire game—including the title skirmish against Vince Lombardi’s legendary Green Bay Packers, on Dec. 26, 1960, which brought the Eagles their most satisfying championship, and their last to date. More than a half-century later, Philly fans of advanced age remember that game as the pinnacle of civic pride, the Billy Penn’s hat of sporting events, and a testament to the city’s working-class grit as exemplified by “Concrete Charlie” Bednarik.

The son of a Bethlehem, Pa., steelworker from Slovakia, Charles Philip Bednarik had a body built for the game—6 ft., 2 in., 235 lb., back when that was mastodon-size—and the requisite remorseless dedication. A two-way star at Bethlehem’s Liberty High School, Chuck enlisted in the Army Air Force and spent the war flying 30 combat missions over Germany as a B-24 waist-gunner. Back home, he played four seasons for the University of Pennsylvania in its brief college-football glory and finished third in the Heisman Trophy vote. In 1949 he became the Eagles’ first draft pick and made All-Pro in eight of his 14 seasons. As much punishment as he dished out, Bednarik could take even more: he missed only three games in his pro career.

With the blue eyes and brutal demeanor of actor Charles Bronson, another rock-solid, coal-country son of Eastern Europeans, Bednarik personified the Eagles as dominant enforcers. Fans saw the players not as faraway star athletes but as guys doing a tough job with honor—in a way, our cops—and for not much money. Signed by the Eagles for a $10,000 salary and a $3,000 bonus, Bednarik never made more than $27,000 a year. The “Concrete Charlie” nickname didn’t refer to his remorseless blocking and tackling; he had to take an off-season job selling concrete to make ends meet.

No question, though, that Bednarik was an artist of legitimate violence: no dirty plays, just the brick-wall force of an immovable object. The words on his plaque in the Pro Football Hall of Fame—”rugged, durable, bulldozing blocker … a bone-jarring tackler”—are almost an understatement, especially to anyone who has seen footage of the November 1960 game in which he leveled Frank Gifford, the Hollywood-handsome running back for the New York Giants, knocking him out of the sport for a year and a half.

A famous Sports Illustrated photo shows Bednarik seeming to exult over the prostrate Gifford. Fifty years later, Bednarik denied the charge—while emphasizing his team’s proletarian underdog status. “I wasn’t gloating over him,” he said. “I had no idea he was there. It was the most important play and tackle in my life. They were from the big city. The glamor boys. The guys who got written up in all the magazines. But I thought we were the better team.” Class resentment aside, that tackle secured a win against the Giants and propelled the Eagles to their Boxing Day title game.

It happens that 1960 was a crucial year for pro football. On the 23rd ballot, the NFL elected a compromise candidate, Pete Rozelle, as commissioner. Moving the league offices from Philadelphia to New York, Rozelle established franchises in Dallas and Minneapolis. The NFL launched this expansion to ward off its feisty rival, the American Football League, which began operations that fall. Six years later, when the NFL swallowed the AFL, creating the Super Bowl, it was well on its way to becoming America’s sport and a multi-zillion-dollar behemoth.

On the day after Christmas in 1960, though, the Big Game was only so big. It was not played in some balmy city with two weeks of walk-up hype; the team with the best division record served as host. The Eastern Division–winning Eagles didn’t have their own stadium; they were tenants at Penn’s Franklin Field. (Bednarik played all his home games, college and pro, in the same place.) Since Franklin Field had no lights, the match started at noon, so that a sudden-death overtime game, like the one two years before between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants, would not be called on account of darkness.

Fans had bought all 67,325 seats for the Eagles-Packers contest, yet the game was blacked out on local TV. You had to drive to New Jersey to watch it. Or you could do what I did as a teenage Philly sports fan: take a train to the stadium and buy a ticket from a scalper. The official price was $8; outside the gates, I paid $6. It was a long time ago.

The Packers would become the most successful franchise of the ’60s, winning five championships, including the first two Super Bowls. But in 1960, quarterback Bart Starr, halfback Paul Hornung and fullback Jim Taylor were figures of promise, not legend. Still, the 8-4 Packers were significant favorites over the 10-2 Eagles. Philly’s squad might have been found at a Germantown garage sale: 12 of the 22 starters were castoffs from other teams. And their wins seemed feats of green magic. In six of their games they were behind entering the fourth quarter; they won six by less than a touchdown. How could their luck hold against the surging Pack?

Playing on a field with some frozen patches and a few puddles where snow had melted, Green Bay penetrated the Philadelphia red zone four times but mustered only six points, because Lombardi, as he later acknowledged, was too greedy for touchdowns. At the start of the fourth quarter, the Eagles trailed 13-10. Ted Dean, one of the team’s three black players, returned a kickoff 58 yards. Later he took a handoff from quarterback Norm Van Brocklin for five yards and the go-ahead score.

In the game’s last minute, the Packers had advanced to the Eagles’ 22-yard line. Starr lobbed a short pass to Taylor, with nothing between him and the end zone—and victory—but Concrete Charlie. Bednarik wrestled Taylor down at the 10 and sat on him as the final seconds ticked away mercilessly. Eagles 17, Packers 13. “You can get up now, Taylor,” Bednarik finally growled. “This damn game’s over.”

A Sports Illustrated photo, taken moments later, shows mud-caked No. 60 with a rare smile as he shakes Starr’s hand and wraps his other paw around the much smaller, defeated Taylor. It never got better for the Iron Man. And for many Philly fans, like this one, it never got as good.

Even in retirement, Bednarik held true to his truculence, criticizing modern pro athletes as “pussyfooters” who “suck air after five plays” and “couldn’t tackle my wife Emma.” He also dismissed the few two-way stars, like Deion Sanders and Troy Brown because, as wide receivers and defensive backs, they weren’t jolted by hard contact on every play, as he had been back in the day.

We should be grateful that the steelworker’s son didn’t soften in his later years; he never tired of being Chuck Bednarik. That’s why his fitting eulogy should be the cartoon that Rob Tornoe drew of Concrete Charlie’s final play: bulldozing his way into Heaven by ripping open the Pearly Gates. For the Iron Man, this damn game is never over.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com