It’s easy to roll your eyes at PR—and easier still when you’re talking about space PR. Space has always been an industry built as much on imagery as engineering.

The Russians tended to go big. Their Yuri Gagarins and Alexei Leonovs became titans of iconography—figures of bronze and steel, their faces cast on coins and their heroic forms raised on pedestals in parks. The Americans went folksy—with reporters and photographers invited into astronauts’ homes while the family ate staged meals or played staged board games, the better to frame the man in the silver pressure suit as just a guy who worked hard and made it big.

MORE: Watch the Trailer for TIME’s Unprecedented New Series: A Year In Space

Similar semiotics were on display this weekend at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, where reporters were invited for a final series of press availabilities as cosmonauts Mikhail Kornienko and Gennady Padalka, and astronaut Scott Kelly prepare for a March 28 launch to the International Space Station—a mission that will include a marathon one-year stay for Kelly and Kornienko. If you came to Baikonur to watch the show—the faux scenes of faux training that played out while cameras fired and reporters tossed puffball questions—it was easy to wonder why the entire kabuki business wasn’t abandoned decades ago. But the kabuki business is a deeply important—even poignant—one, and the job of spacefaring would be much the poorer without it.

MORE: Meet the Twins Unlocking the Secrets of Space

Baikonur looks like what it is, which is to say a company town, albeit it one built for a very particular employer at a very particular time in its history. Much the same is true of the space coast of Florida and the communities around the Johnson Space Center in Houston—but much is different, too. The developers in Houston and Canaveral gave their neighborhoods names like Timber Cove and Cocoa Beach, and built ranch homes and beach houses in a ramble of neighborhoods and along strips of sand. If you worked there and lived there and ever tired of life there, you could always up sticks and move into the private sector.

Baikonur is known as, well, just Baikonur, a development of Soviet-era bleached-cream housing blocks built along paved-over promenades for families working in the service of the space center. Here too, you were always free to walk out of town, but once you did you’d find yourself in the Kazakh steppes, and there was no work to be had anywhere else, so best to stay where you were.

Today, Baikonur is the same—only older. The bleak Soviet housing is now bleak and flaking Soviet housing, and while there is a new hotel near the space center that, graded on a Kazakh curve, has a certain glitter to it, the space program as a whole is a much-reduced thing. Gone are the Mir and Salyut space stations. Gone are the unmanned missions to the moon and the planets. All that survives are the Soyuz rockets launching three-person crews to the space station, with seats going for north of $70 million each—a fat revenue stream for the modern Russian state, but one which will be choked off in 2017, when new manned spacecraft built by SpaceX and Boeing start flying.

Astronaut Twins: Mark and Scott Kelly, the Early Years

But Baikonur is more than a space-age theme park. Much like the rest of the old Soviet Union, it’s a city where space has always been something of a secular faith. There are sacred spaces—the massive replica of a Soyuz rocket in the center of town, where, on an overcast day this weekend, a bride and groom danced at the center of a circle of twirling children. There is the alley of cosmonauts on the space center grounds, where every man or woman who has launched from here has planted a poplar tree before leaving Earth, beginning with Gagarin’s—the tallest and, at 54 years old, the oldest.

And into all this history this week, stepped Kelly and Kornienko and Padalka, still on the Earth but already disengaging from it. The press crowded in as the men were put on display, but they approached no closer than three meters, and no one could come even that close without clearing a medical screening and donning a surgical gown and mask, lest they pass on a cold or flu.

The three crewmen and three backup crewmen posed with a flight director and pretended to review procedural manuals, then worked at computer screens and pretended to run a docking drill, while the cameras flashed and flashed. They played at playing, too—10 minutes of ping pong and pool and badminton staged for the cameras. They’re boys, after all, and they work hard and play hard and the rough camaraderie and competitiveness that comes from that is just what they’ll need in space.

Kelly, who’s making his fourth flight, knows the drill well. “Misha, rematch!” he said to Kornienko as they approached the pool table, as if they do this every day. He knows too to poke gentle fun at the drill. “I wonder if they’ll notice if I pedal backwards,” he said to nobody in particular as he worked a stationary bike for a gym photo op.

And it all could have seemed too much, it all could have seemed too silly. But then, at the end of the day, the six crewmen came to visit cosmonaut alley. They walked past Gagarin’s tree first, and they walked past many others too—like the one planted by Leonov, the first man to walk in space, or Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. But they also walked past those of the three men of Soyuz 11, who planted their poplars in 1971 and then flew off to space and never touched ground again—or at least never touched it alive because their spacecraft depressurized during reentry and they thumped down on the same Kazakh steppe dead from asphyxiation, cold and silent when the rescue team opened the hatch.

All three prime crewmen for the upcoming mission have flown from Baikonur before, and all three thus already have trees, so they simply watered them for the photo op. Kelly’s is still little more than a twig, and he gave it only about half of the bucket of water he’d been provided. “I don’t want to drown him,” he said.

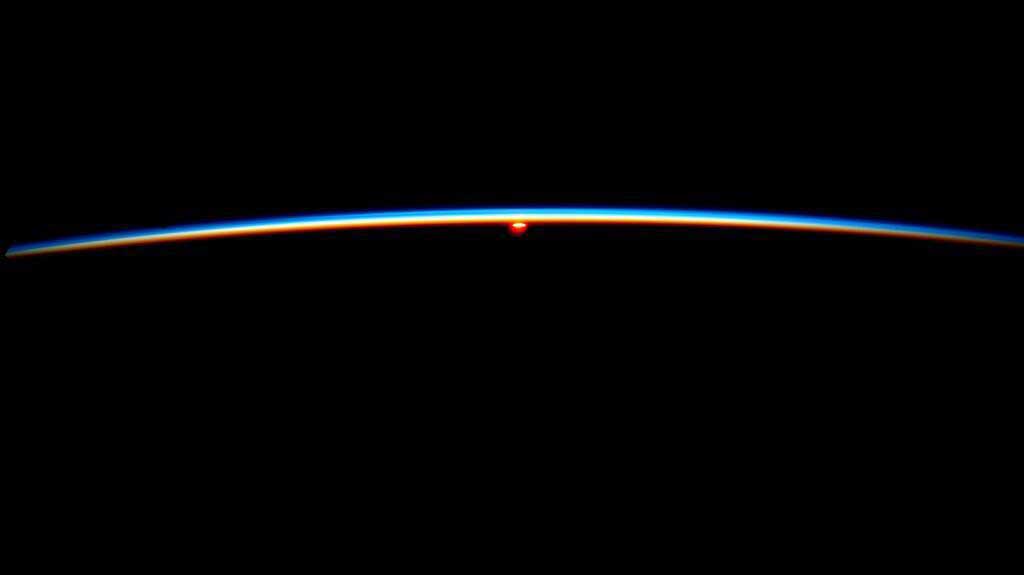

The pronoun, the him, was playful, but it was something more too. Kelly has two daughters—very much a pair of hers—and he’s spending a year in a place from which some people do not return. He knows that he’s leaving his girls and his friends and his family and his tree, that he’ll be gone till this time next year and would very much like to come home and see them all again.

The magical rituals—the wedding dance and the tree planting and yes, the staged press op where reporters are told to stand at a respectful distance and take the pictures they’re offered because the men and women who are the subjects of your shots are going into space and, let’s be honest, you’re not—have been part of the space fabric for a long time. Baikonur is a place built on such things, and the fact is, after half a century, far more cosmonauts have come home to see their trees than haven’t. The old ways, for better or worse, seem to work.

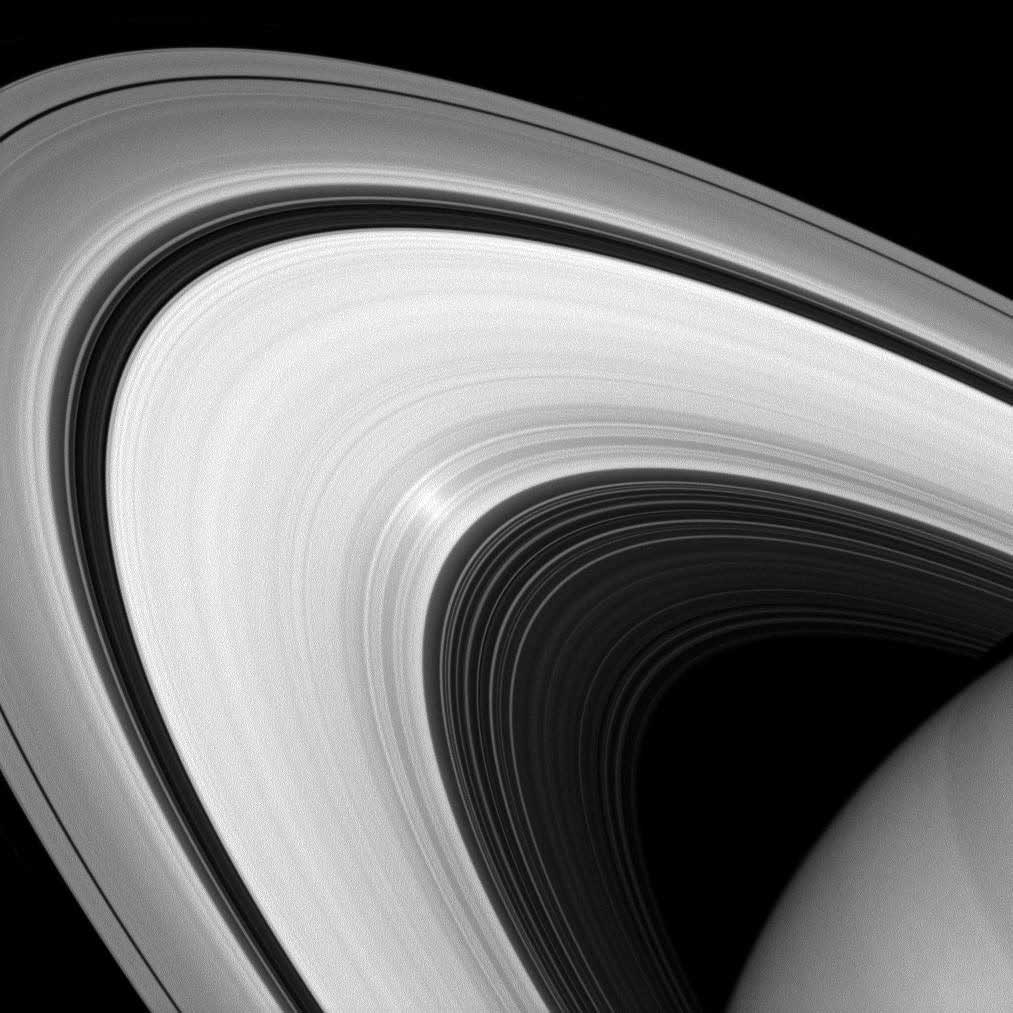

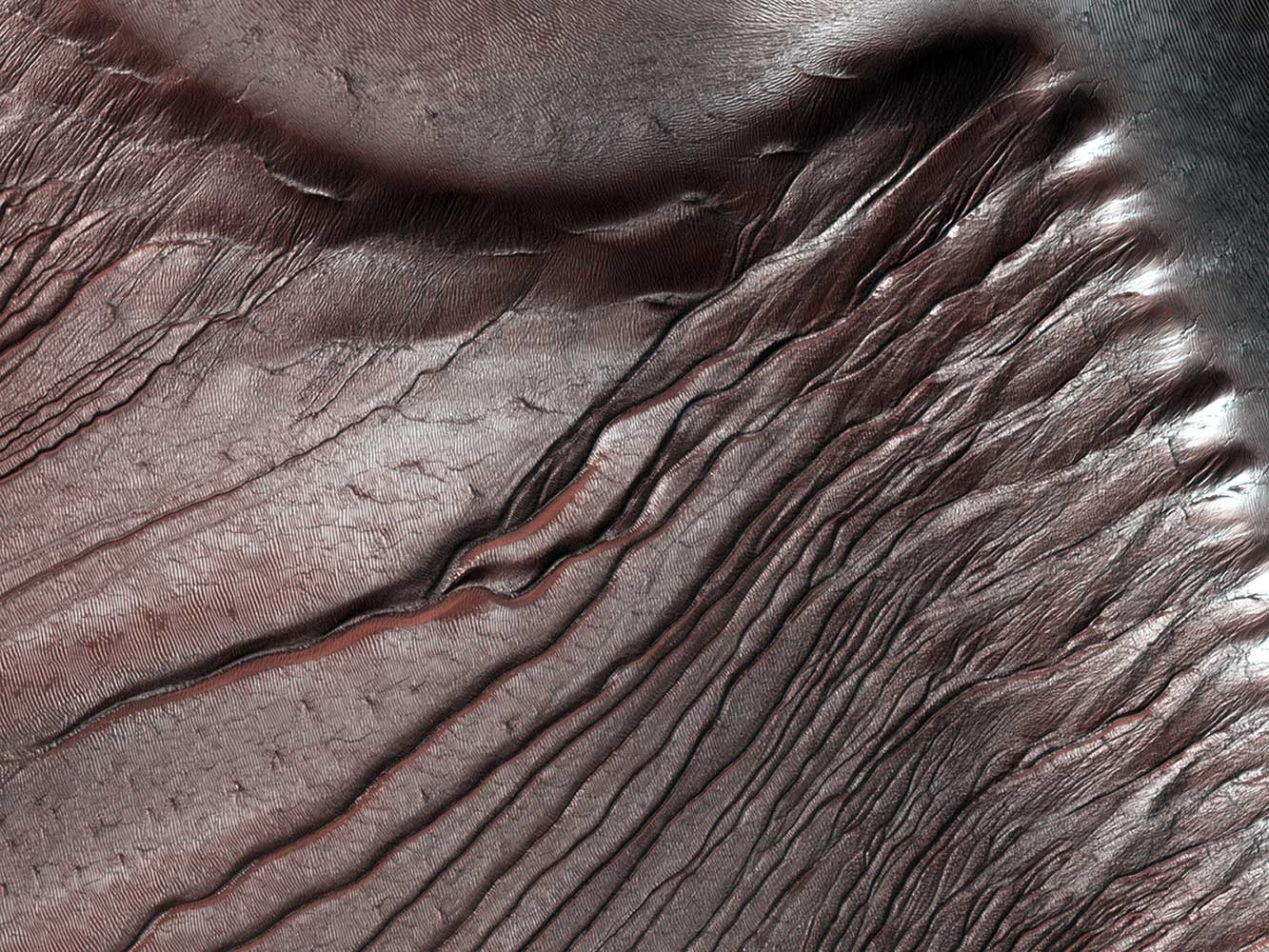

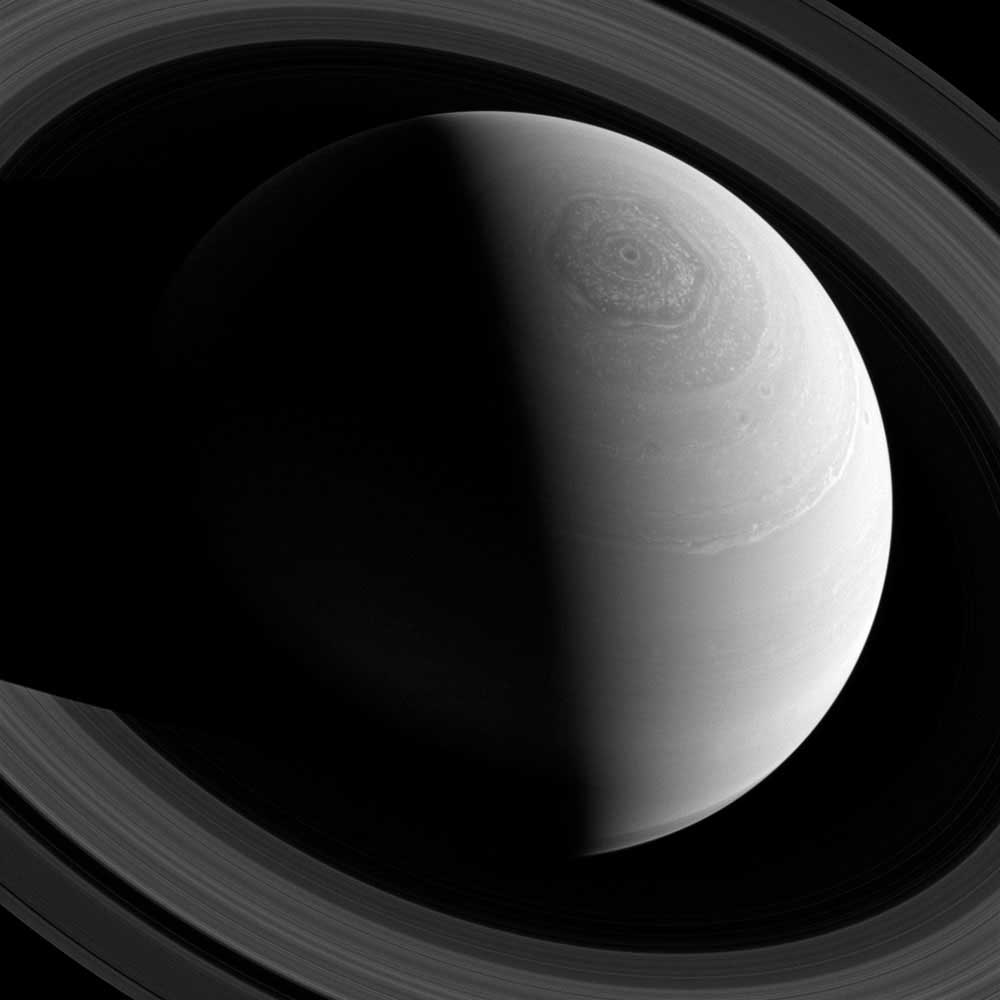

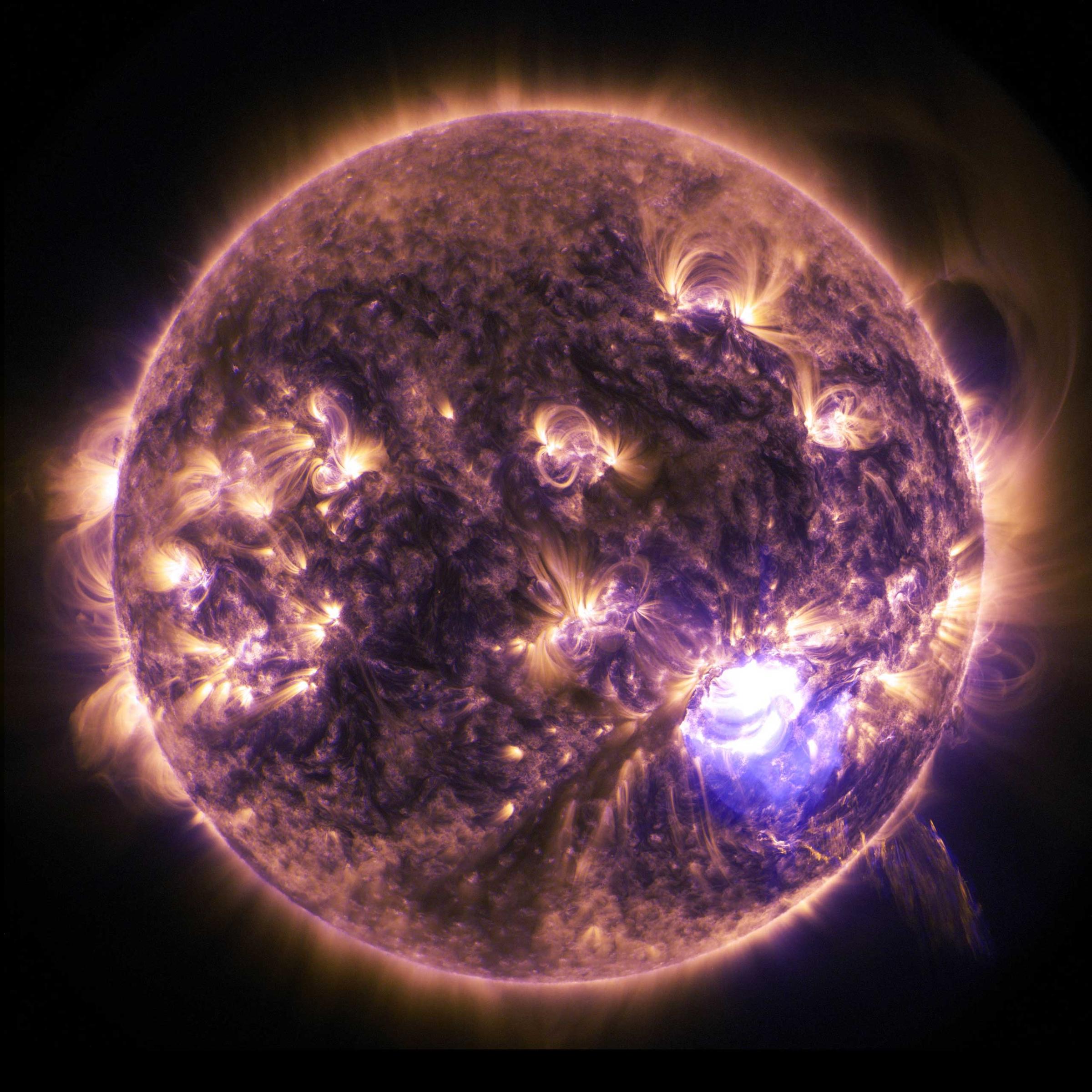

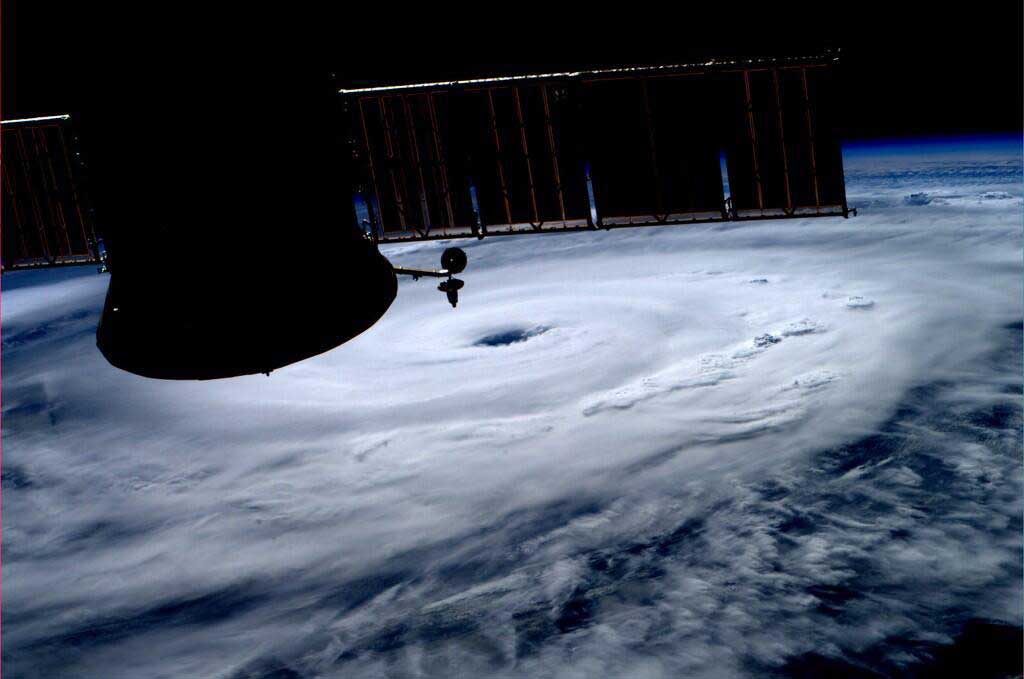

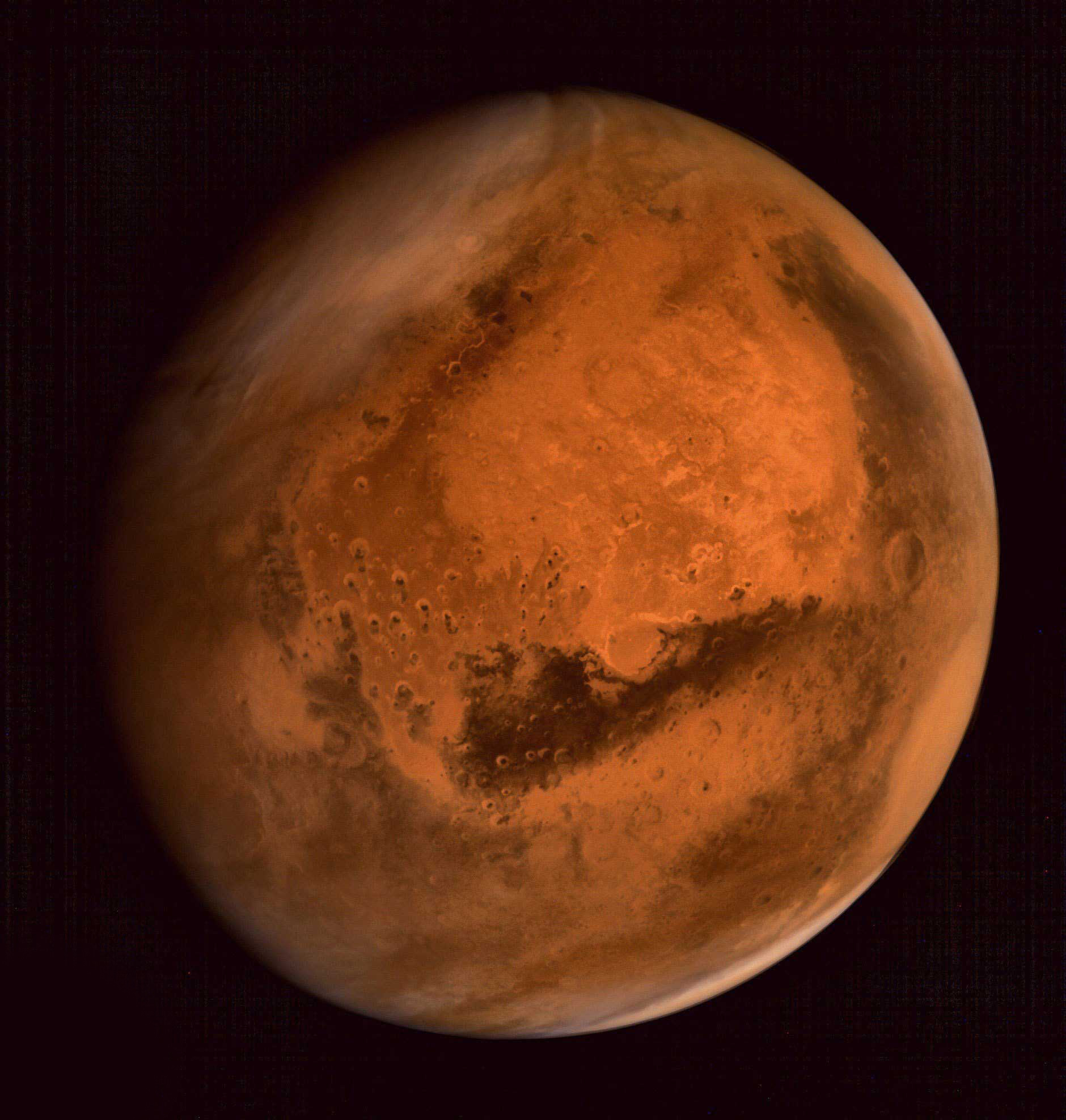

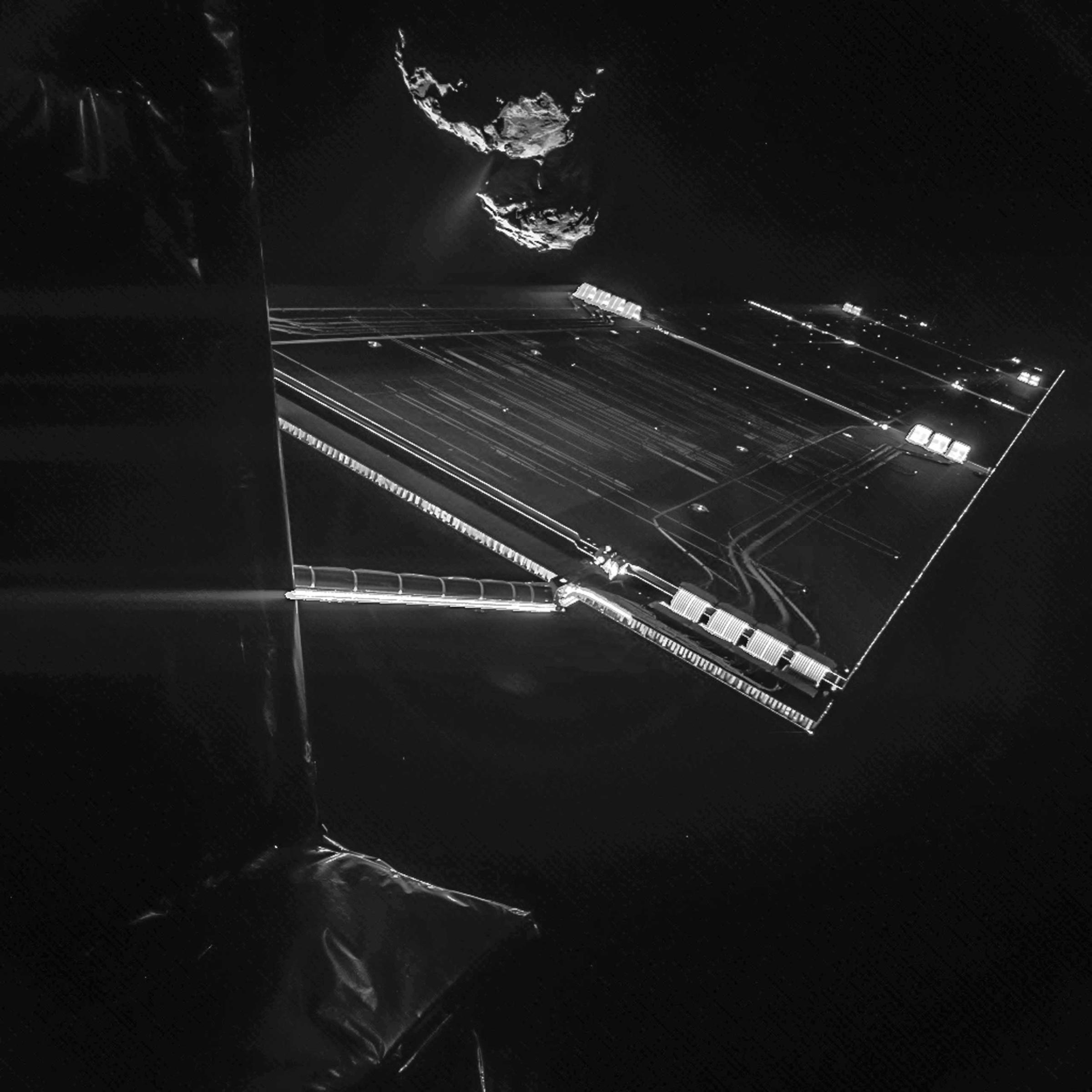

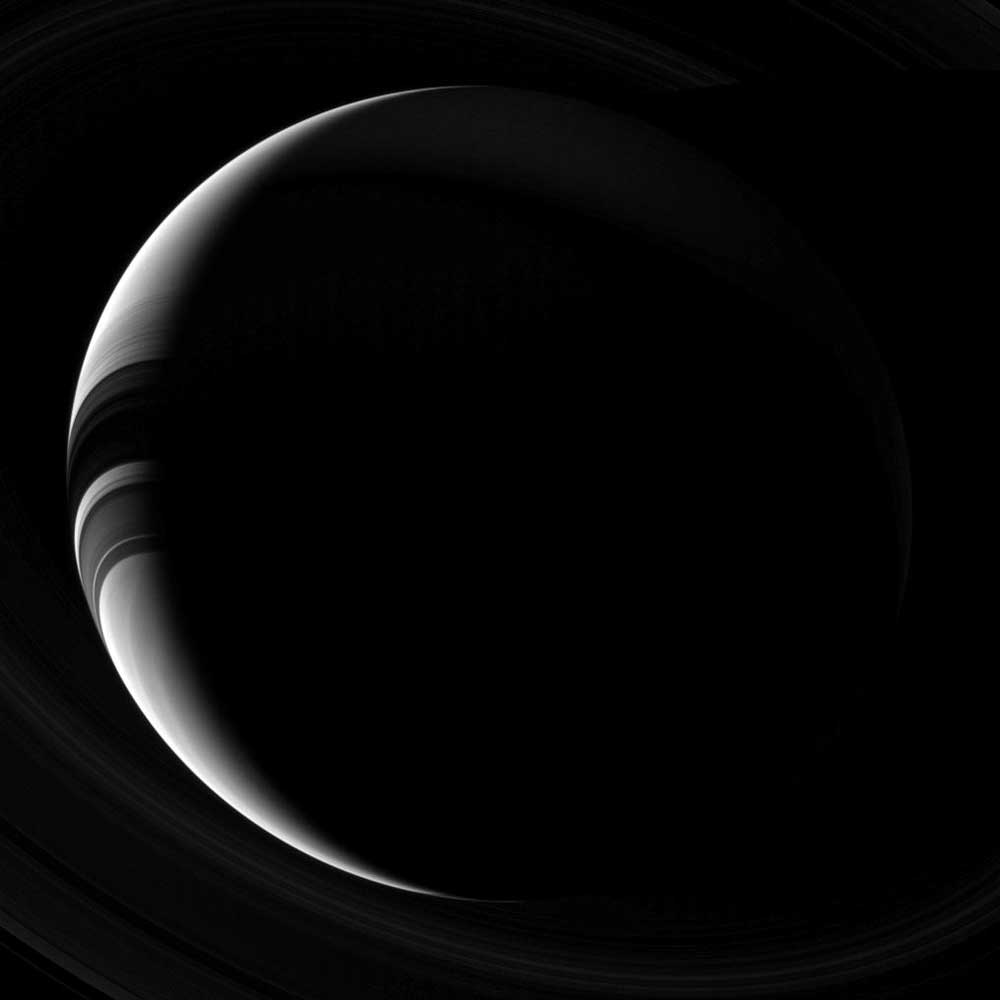

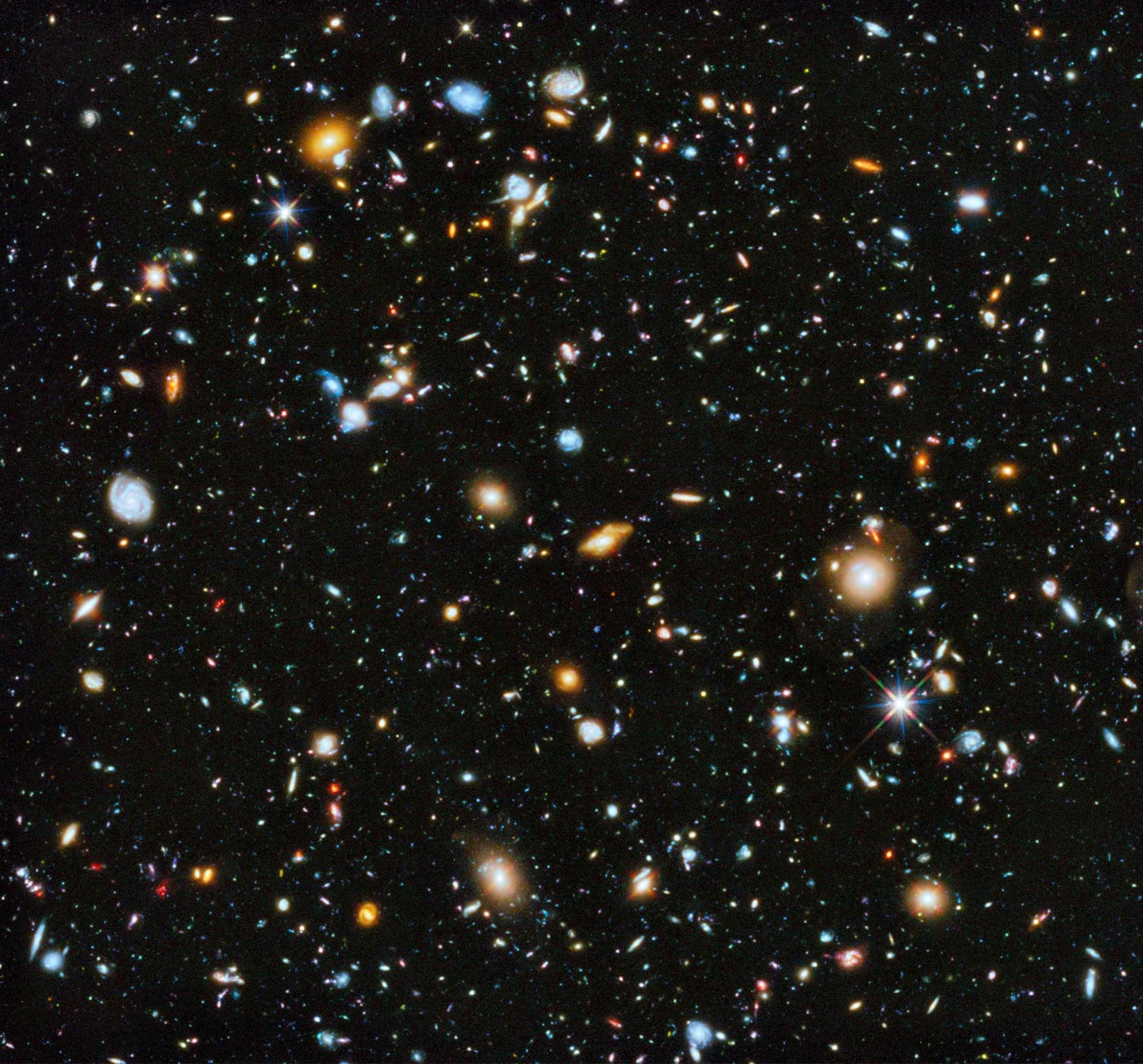

See the Most Beautiful Space Photos of 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger / Baikonur, Kazakhstan at jeffrey.kluger@time.com