Of all the apps and services I’ve ever signed up for, the only one I remember plugging my username into for the first time is Twitter. It was May 2007, and I was about to quit a job full of people I loved working with to move across the country and go it alone as a freelancer.

Still relatively new, the 140-character messaging system was originally dreamt up as a small group SMS service, and that’s how I intended to use it. I told my friends to join Twitter so that during my cross-country drive, I could regale them with my hilarious observations and updates.

No one signed up — not even my family.

Funny enough, it wasn’t for another another seven months that I made my first post on Twitter, but I’m reminded of this story with March 21, the ninth anniversary of the first ever tweet, just around the corner.

Since that time, the service has evolved in ways that few people, if anyone, could foresee — so much so that Twitter is now a company valued at more than $30 billion. But that figure doesn’t care a lick that the service was SMS-based back when I signed up, or even that it has 288 million users today. Stock market numbers only care where a company is headed, and when it comes to Twitter, that’s the most interesting thing of all.

According to company lore, the service got its first shot of what we now call “social amplification” at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Interactive Festival in March 2007, when bloggers, coders, and techies of all stripes took the service, enticed by tweets displayed on flat-panel screens in the hallways, then a tech show’s novelty which has since become a conference stalwart.

“I thought it sounded like an atrocious waste of time — it sounded trivial and like a distraction — and I didn’t want to have anything to do with it,” says Marshall Kirkpatrick, then a writer for TechCrunch and a SXSW attendee who signed up for the service that month. Kirkpatrick only planned to use Twitter to gather information to make the most of his festival experience. Afterwards, he was going to shut down his account.

“Of course, it didn’t end up that way,” he says.

After SXSW, Kirkpatrick continued to use the service to break stories well before his competition by following software engineers and people working in the middle of organizations, rather than company founders and outspoken evangelists. In fact, Kirkpatrick got so adept at Twitter that even Mashable has said it learned how to use the social network to uncover stories by watching him. Yet perhaps the most remarkable thing about the stories Kirkpatrick broke — such as the launch of Google+, months before it was even announced — was that he did it all from a perch outside Silicon Valley in Portland, Ore.

“The great thing about Twitter is that it’s global, it’s real-time, anyone can publish, and anyone can read, as well,” he says.

And in that way, Twitter has decentralized, well, everything. When you think of your favorite Twitter follows and followers today, you probably don’t even consider where they are located. Whether they tweet about conservative politics, the Detroit Lions, luxury watches, or home brewing, Twitter users seem to be located online more than any real geographic spot. And over the past nine years, as the service has grown in users, matured in its usage, and evolved from being a chatterbox for San Francisco-based techies to a mainstream, worldwide mode of communication, Twitter has either aped the trend of location-agnostic expertise, ushered it in, or both. This has not only had a profound effect on our economy, but also in how we get work done.

To whit, four and a half years after vowing to quit Twitter, Kirkpatrick founded Little Bird, a company that mines the social web to find topic-based influencers for marketers. With at least $3.4 million in funding from various venture capital investors including Mark Cuban, the company now boasts big name clients like Comcast and IBM. But more importantly, Little Bird shows how Twitter has allowed someone to move from selling his information to selling his expertise, a distinction that might seem fine but becomes markedly different when counting all the extra the zeros on the checks. And nine years in, that’s the difference between a 140-character messaging service and a $30 billion economic force, if only through one example.

With one billion tweets sent nearly every two days, Twitter has become something nearly impossible to describe, because it’s different for every user. Though I never actually used it to liveblog my road trip, it’s likely that millions of other people have. And while Kirkpatrick used Twitter to dredge up stories, I treat the network as my virtual water cooler, a place where I can chat with co-workers and peers, even though I work alone. Meanwhile, some use Twitter to curate their news sources, while others rely on it to follow stories as they break. From Abbottabad to the Boston Marathon to Ferguson, Twitter consistently beat the press as the events unfolded, making journalists like myself wonder if guys like Kirkpatrick were ahead of the pack, yet again, getting out of this line of work.

Read more: Twitter Looks Back on Its 9-Year History, in Tweets

But all those examples are narrow in scope to my experience with Twitter. Entire conferences run their commentary on the site. Software and machines are driven by tweets. Mobile payments run across the service. People can now use their phones to broadcast video to millions, at a moment’s notice, over the social network.

So today, Twitter is — as Kirkpatrick puts it — a big, noisy channel of human communication. But as proud as we are of our tweets of Babel, that means the social network is also chock-full examples of humanity at its worst. In the highest-profile examples of our shamefulness, Twitter has disassembled people and careers before the public’s very eyes. And at its most hateful, the short messaging site has pushed beyond cyber-bullying into real-world suicides, a horrid reality that makes us wish this thing really was just a trivial distraction, after all. Most recently (and notably), Gamergate, Curt Schilling, and Ashley Judd, have begun to show Twitter users that just because you can, that doesn’t mean you should. But then again, if hundreds of thousands of years of evolution haven’t taught us to mind our manners, 140 characters are unlikely to either.

As to what Twitter itself will become over the next nine years, that’s anyone’s guess. Critics argue that the service needs to find a way to manage its noise, while investors want to see more users take to the site (making the task of wrangling those tweets even more important). Meanwhile, fans laud Twitter’s firehose of a feed, a key differentiator between it and Facebook. But if we’re going to mention the other major social network, it’s worth noting that Zuckerberg’s baby has almost five times more users, with 1.39 billion monthly actives.

To match Facebook’s reach, Twitter must find a way to lure users who — despite being deeply (if obliviously) affected by the short missives that flash across its transom — still deem it a giant waste of time. Remarkably, for a site so influential, nine years in, most people I know in the real world still don’t use Twitter. Not even my family.

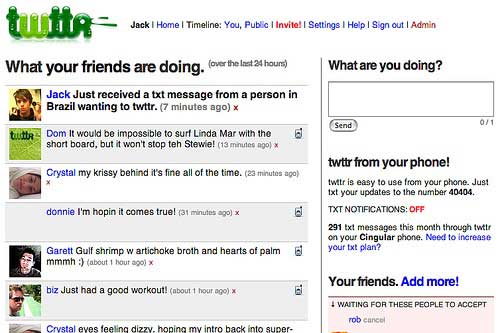

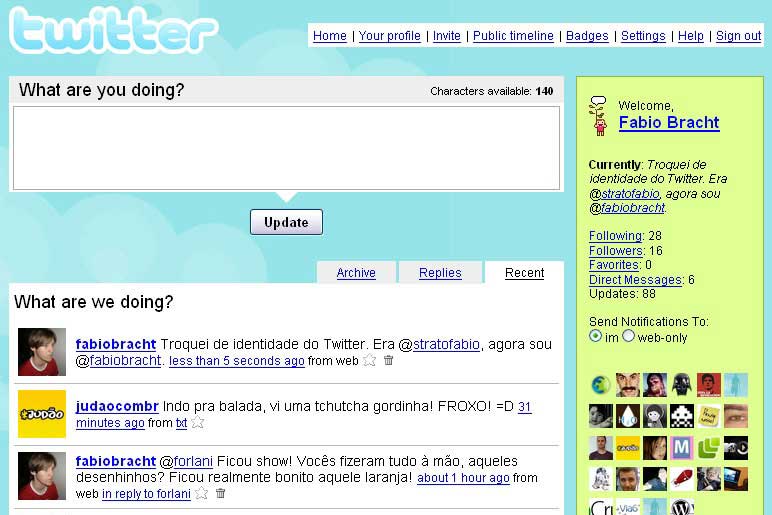

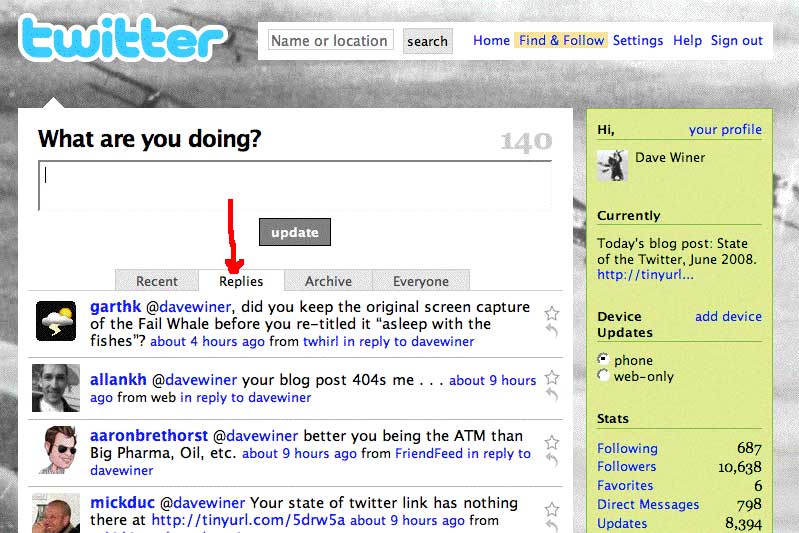

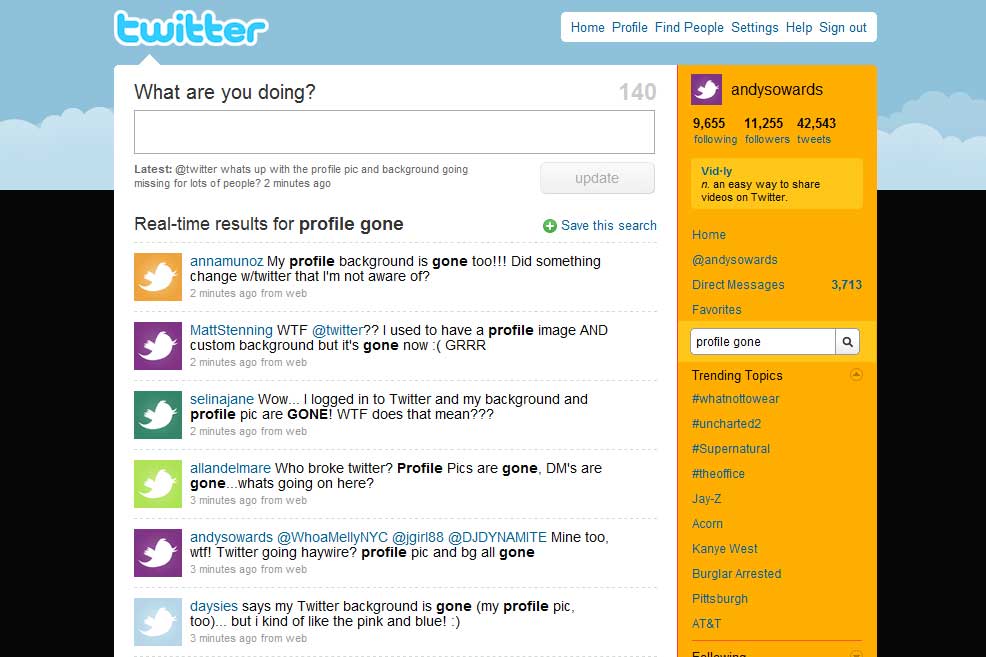

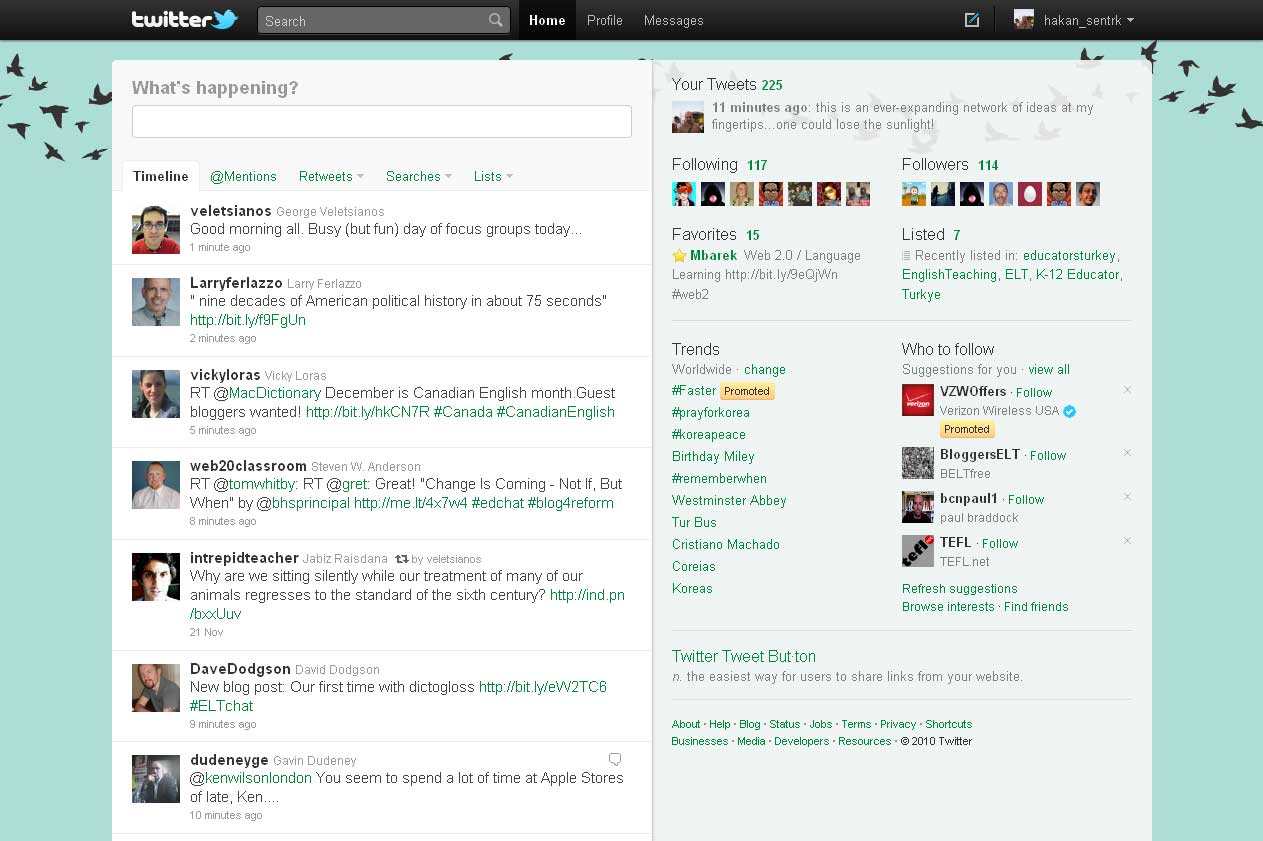

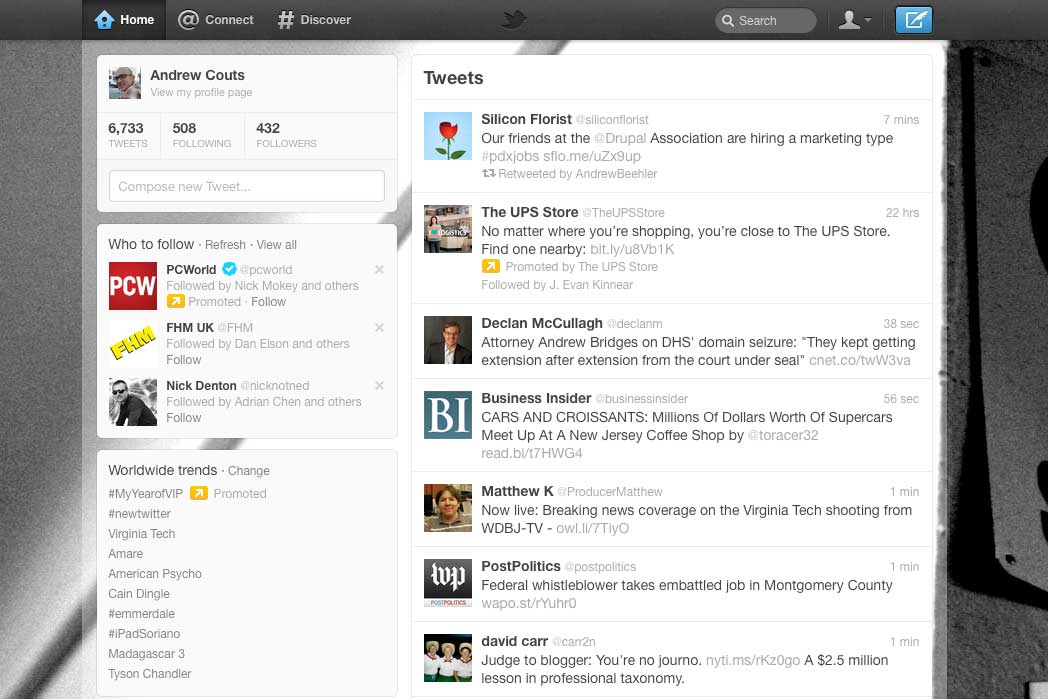

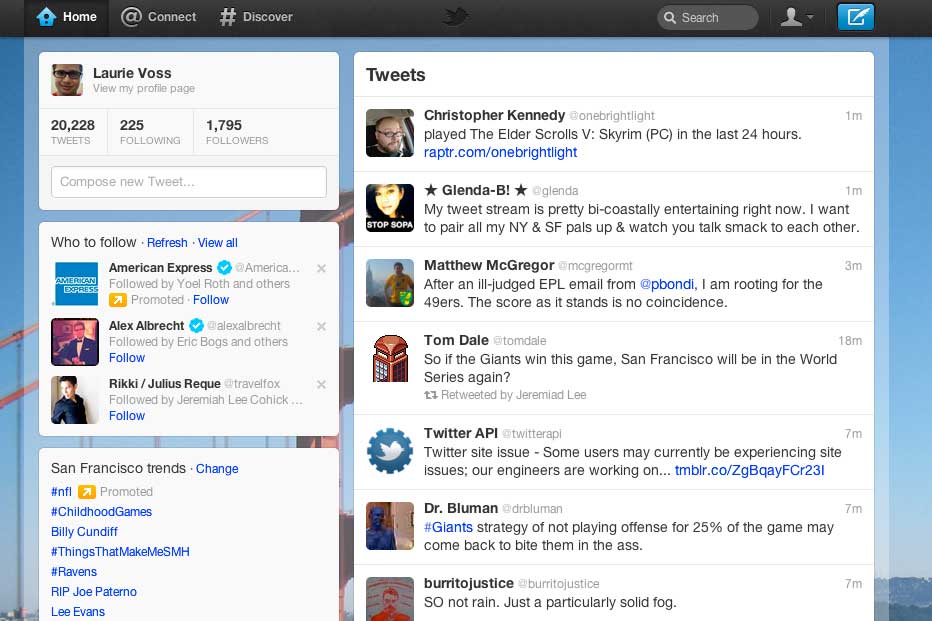

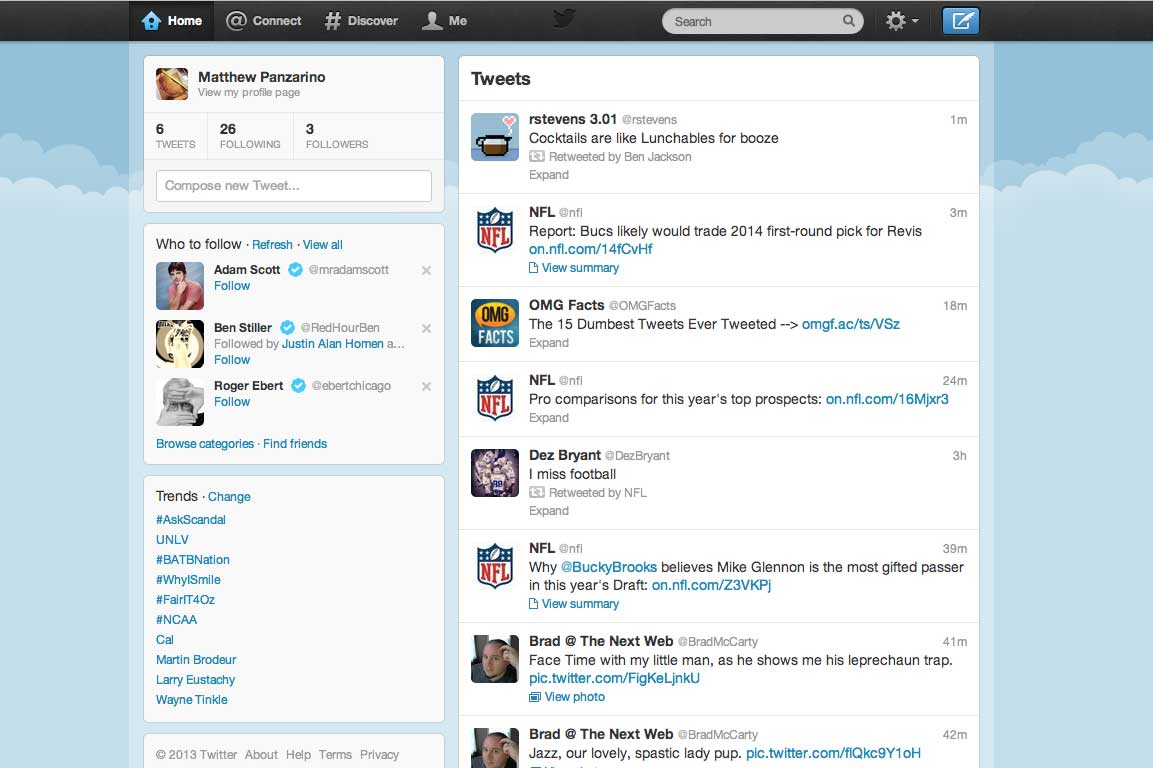

See What Your Twitter Profile Looked Like Over the Last 10 Years

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com