The Great Wall of China is one of the world’s most popular destinations in Asia.

Referred, in the country, as “The Thousand-Mile-Long Wall,” the site was once thought to be visible to the naked eye from outer space, although that claim has since been proven to be false.

Yet, certain sections of the wall – perhaps the most majestic and photogenic, which are open for tourism — were rebuilt by the Chinese government in the 1970s and 80s. The widespread imagery of a refurbished Great Wall meandering through long sweeps of green mountains in rural Beijing, has not only shaped outsiders’ imaginations of an ancient country replete with rich history, but has also helped China build for itself a national identity and pride.

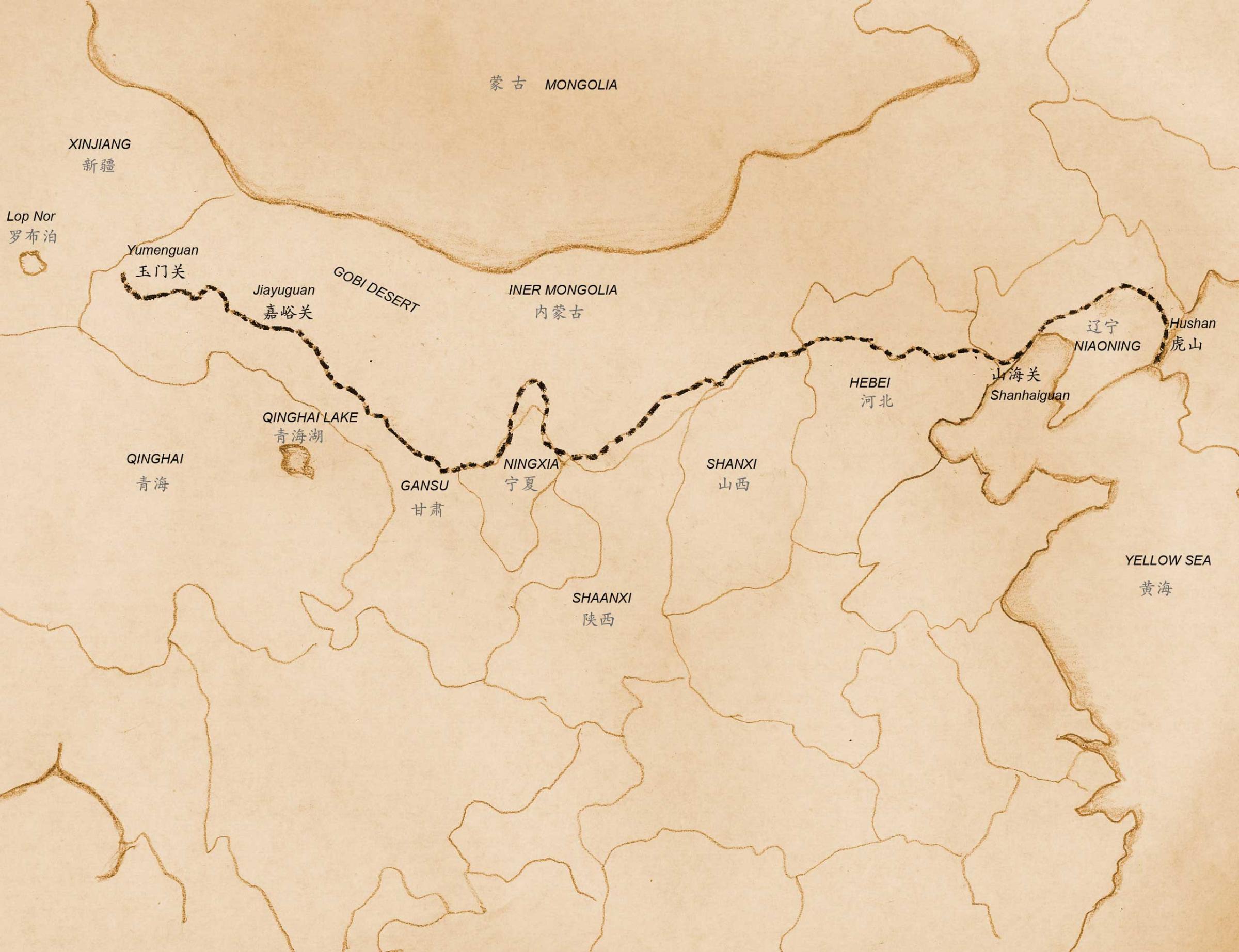

In 2013, Chinese photographer Fan Shi San cycled 4,000 miles along the Great Wall from west to east in three months, with the goal of building a visual archive of the country’s most symbolic construction. What he discovered was far from what he’d imagined.

“When I was photographing along the actual walls, the scenes I encountered constantly overthrew and reconstructed my own idea of the Great Wall and China,” Fan tells TIME.

The idea of the bike trip first came to him after reading American journalist Peter Hessler’s Country Driving: A Journey Through China Farm to Factory, a book that closely examines the wild great walls north of Beijing and life in their nearby villages. “I did get a driver’s license just for this project,” Fan says, “but traveling with a car is too costly, so I started looking into cycling.”

Initially, Fan feared the harsh climate and wild animals in the less urbanized areas of western China. “I didn’t have a lot of experience in camping and long-distance cycling,” he says. But after cycling for hundreds of miles, he began to treat the journey not as an unconquerable task but as daily life with a different routine. “I would leave when the sun rises and stop when it’s down,” he says. On an average day, Fan cycled for about 40 to 60 miles, and either camped on the roadside at night or found accommodations in towns and villages, where he could stock up and take a shower.

“I would ride my bike slowly, photograph things that caught my eyes, and talk to people who interested me,” he tells TIME.

The fortifications, stretching across several provinces in northern China, were rebuilt and expanded throughout dynasties, and changed in the hands of numerous emperors. It carries not only the depth of China’s history, but also the geography and culture diversity of communities near them.

In the far-reaching regions such as Gansu and Shanxi provinces, where the walls were built by rammed earth with bare hands, and where the government has little oversight or interest in historic preservation, the heritage is left open to erosion by an extreme desert climate and careless human degradation.

Some villages and towns in the remote areas are slowly dying “in the progress of the reborn country’s industrialization and urbanization,” he says.

In some communities, Fan saw children playing in large groups on the streets without a guardian. Their young parents had handed them to grandparents before migrating to find work in overcrowded factories on China’s populous coastline. There, they hope to find a promising future, one that isn’t vanishing like the country’s old great walls.

Fan Shi San is a freelance photographer based in Shanghai. His work has been exhibited in China and the U.K.

Ye Ming is a contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com