In late 2013, Satoru Iwata sat alone on a bullet train headed toward Tokyo. As the carriage sped silently down the track, Iwata, the puckish CEO of Nintendo, began sketching out a new idea: a line of physical toys with built-in chips that connected wirelessly to the company’s varied game systems. The toys would let Nintendo trade on its universe of characters like Mario and Donkey Kong while generating new sales.

Iwata, a 55-year-old who dresses in three-piece suits and speaks in measured phrases, often pausing to chuckle, says he got more and more excited as he mulled the concept. He dashed off a four-page pitch to his engineers. “It was something I believed would be completely new for us,” he recalls. The result was an array of figurines dubbed Amiibo (Japanese wordplay meant to evoke friends playing together), which launched worldwide a little less than a year later and turned out to be a hit. Nintendo says it sold nearly 6 million figurines, which go for about $13 each, by the end of 2014.

Amiibo was a badly needed success for Nintendo—but one that underscores the difficult position the video-game pioneer finds itself in. The company that generated enormous profits in the 1990s and 2000s by introducing innovations in game controls and forcing rivals to adopt its ideas now at times follows in the footsteps of the competition. The gamemaker Activision has been selling similar toys since 2011, grossing nearly $3 billion. Disney, meanwhile, has its own version, based on movie characters such as Buzz Lightyear and Captain Jack Sparrow.

Nintendo has been struggling for years. Wii U, the successor to the wildly popular Wii, has sold just under 10 million units since its launch in 2012. (From 2006 to 2014, Nintendo sold more than 100 million Wiis. And Microsoft and Sony, which launched competing systems after Wii U, have both outsold it.) Last summer, Nintendo laid off over 300 employees in Europe. And the company’s return to modest profitability late last year, thanks in part to a weaker yen, materialized after three consecutive years of losses. Nintendo’s critics have been relentless in demanding that the company abandon its hardware business and make versions of its games for smartphones and tablets.

MORE Exclusive: Nintendo CEO Reveals Plans for Smartphones

On March 17, Iwata announced what many—including Nintendo’s own executives—long thought impossible: the company will begin making games for mobile devices. Nintendo is striking a partnership with Japanese mobile gaming giant DeNA to establish a smart device gaming platform to be introduced this fall. The alliance includes a cross-shareholding agreement: Nintendo is buying a 10% stake in DeNA for $182 million; DeNA is acquiring a 1.24% stake in Nintendo for the same amount.

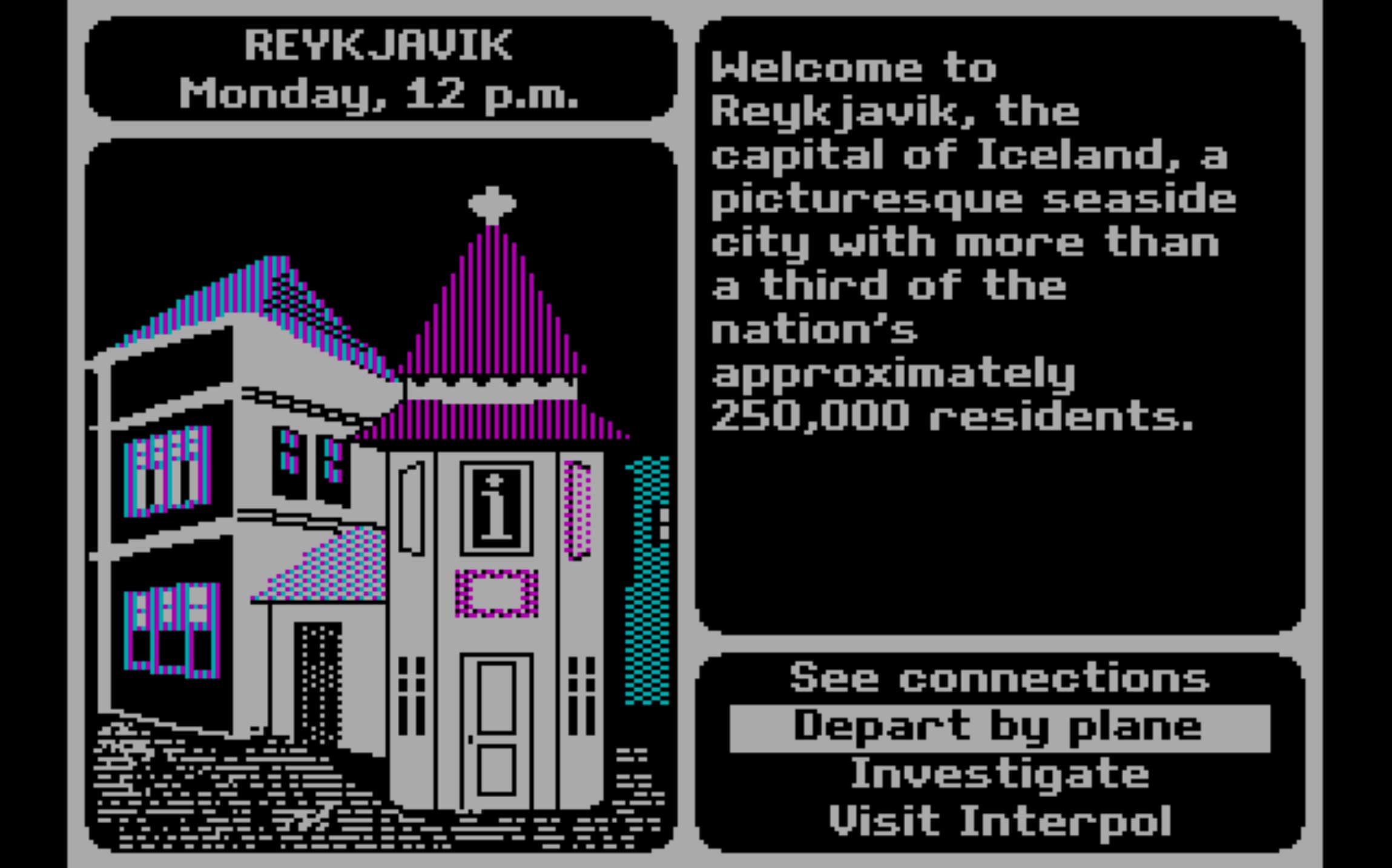

It’s not hard to see why Nintendo is reversing course now. Research firm Gartner reported global smartphone and tablet sales of over 1.4 billion units in 2014. By contrast, the two best-selling video-game systems of all time—Sony’s PlayStation 2 console and Nintendo’s DS handheld—each took nearly a decade to sell 150 million units. Meanwhile, smartphone gamemakers like King (Candy Crush) and Rovio (Angry Birds) are now worth billions. And mobile knockoffs of 1980s classics have turned into overnight hits (see: Crossy Road and Flappy Bird), while Mario, Luigi and friends have not yet been found on a phone.

Why now? “In the digital world, content has the tendency to lose value, especially on smart devices,” Iwata tells TIME exclusively. “We finally found solutions to the problem. We will not merely port games developed for our dedicated systems to smart devices just as they are—we will develop brand new software which perfectly matches the play style and control mechanisms of smart devices.” The ultimate goal: to drive tablet and phone users to Nintendo’s hardware such that they “eventually become fans of our dedicated systems.”

Nintendo’s senior leaders rarely talk publicly about internal strategy. But the company’s top three executives recently agreed to speak with TIME and insisted that Nintendo is not out of big ideas. (Please click here for full Q&As with Iwata and Miyamoto.) The about-face on mobile devices is just one example, they argue. The firm is busily retooling to create new products, like Amiibo and its new 3DS handheld, released in February, more quickly. And Nintendo is opening up by broadcasting presentations—sometimes serious, sometimes silly—directly to its fans to combat a reputation for flat-footedness. All of these moves are part of a company-wide effort to reinvigorate the Japanese icon.

Not on the agenda: abandoning hardware. In addition to its revised mobile strategy, details on a new Nintendo platform codenamed “NX” are due next year. Iwata argues that pressure to get out of that business has always reflected a deep misunderstanding of the company’s approach to innovation. “We view it as that marriage of the software with the hardware that together creates a compelling experience,” says Reggie Fils-Aimé, Nintendo of America’s president. Iwata concurs, explaining that dropping out of hardware would cripple the company. “If we don’t take an approach that looks holistically at the form a video-game platform should take in the future,” he says, “then we’re not able to sustain Nintendo 10 years down the road.”

Humble Origins

Nintendo is a much older company than its signature candy-colored protagonists suggest. Founded in Kyoto in 1889 by artist turned entrepreneur Fusajiro Yamauchi, the company began as a manufacturer of handcrafted playing cards. The Nintendo most people know was born in 1966. That’s when Hiroshi Yamauchi, the firm’s longest-serving president (from 1950 to 2002), greenlighted a gadget that employed crisscross slats and a scissors-like handle to make an extensible arm. It sold millions of units and paved the way for a series of quirky playthings that included early electronic games in the 1970s.

More recently, the company has been run as a creative troika, with Iwata at the top and presidents in both Europe (Satoru Shibata) and North America (Fils-Aimé). Shigeru Miyamoto, the storied creator of Donkey Kong, Mario and Zelda, is the company’s creative genius and currently the general manager of its R&D division.

MORE Exclusive: 7 Brilliant Insights from Nintendo’s Gaming Genius Shigeru Miyamoto

That division’s approach to game design can sound counterintuitive. Conventional wisdom holds that consumer-electronics manufacturers should first design a game system, then lure third-party software developers to furnish it with hits. Nintendo says it does the opposite: it experiments until it finds something its existing systems can’t do—motion sensors in the case of the Wii, or a touchscreen for the Wii U—then makes the hardware to support it. “Our job is to continue to create new platforms that enable us to create fun new ways to play,” says Miyamoto.

Mobile games will present a new set of challenges for the company. Many of that market’s biggest hits are initially free to download but generate enormous sales by constantly prompting users to pay small amounts for in-game items. Iwata says this doesn’t track with Nintendo’s identity. “Nintendo does not intend to choose payment methods that may hurt Nintendo’s brand image or our intellectual property,” he says. That doesn’t mean so-called micro-transactions are entirely out of the question, however. The company will decide which payment system to employ depending on the title, Iwata says. He adds: “It’s even more important for us to consider how we can get as many people around the world as possible to play Nintendo smart device apps, rather than to consider which payment system will earn the most money.”

How the firm deploys its vast library of beloved characters is another major decision. Nintendo says this stable of characters will be an asset as it enters a new, rapidly changing market. It plans to develop multiple titles simultaneously. “We would like to create several hit titles by effectively leveraging the appeal of Nintendo IP,” Iwata explains.

Nintendo’s executives are adamant that creating dedicated hardware is a core part of its creative process. That is why the announcement of new mobile titles coincided with the announcement of a new platform, the NX. “For us to create unique experiences that other companies cannot, the best possible option for us is to be able to develop hardware that can realize unique software experiences,” explains Iwata.

And, Iwata argues, there is a symbiotic relationship between the world’s iPhones and Android devices and Nintendo-made hardware. “Even before the advent of smart devices, we employed touchscreens for our games with Nintendo DS, and we also adopted accelerometers for our Wii Remotes faster than smart devices did,” he explains. “By utilizing our unique know-how in areas like these, I believe we will be able to come up with unique propositions for consumers.” Nintendo is planning to elaborate on how exactly this will work for specific titles over the coming months.

For now, Nintendo’s biggest seller remains its 3DS, a handheld successor to the Game Boy introduced in 2011. It is designed to appeal to all ages but is most popular among younger players. That’s partly about parents. In a world flush with smartdevices that can tap the entire Internet—including unsavory fare—Nintendo’s handhelds are relative walled gardens of controversy-free content. The 3DS can go online, but only if parents have set the device’s privacy controls to allow it.

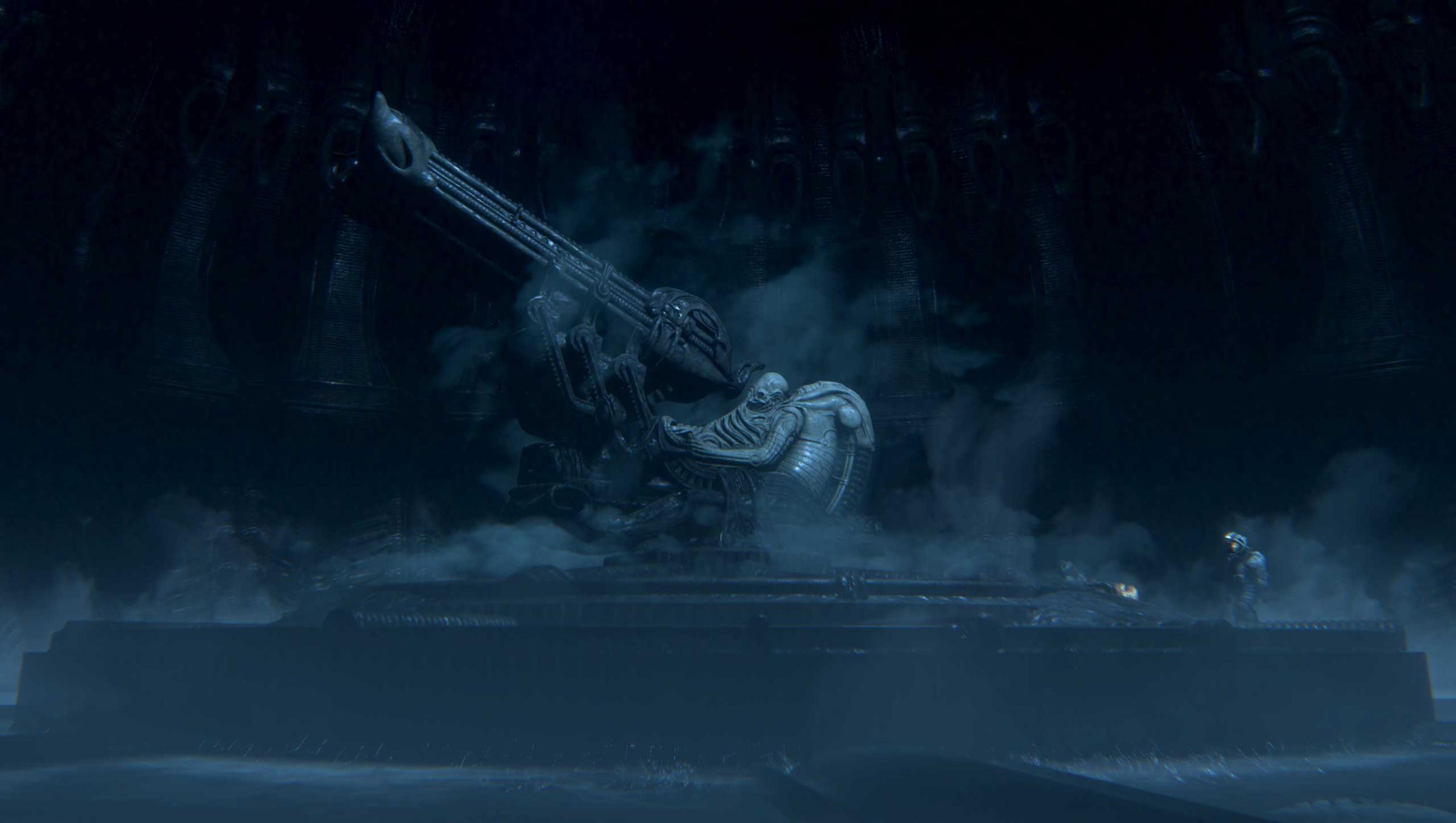

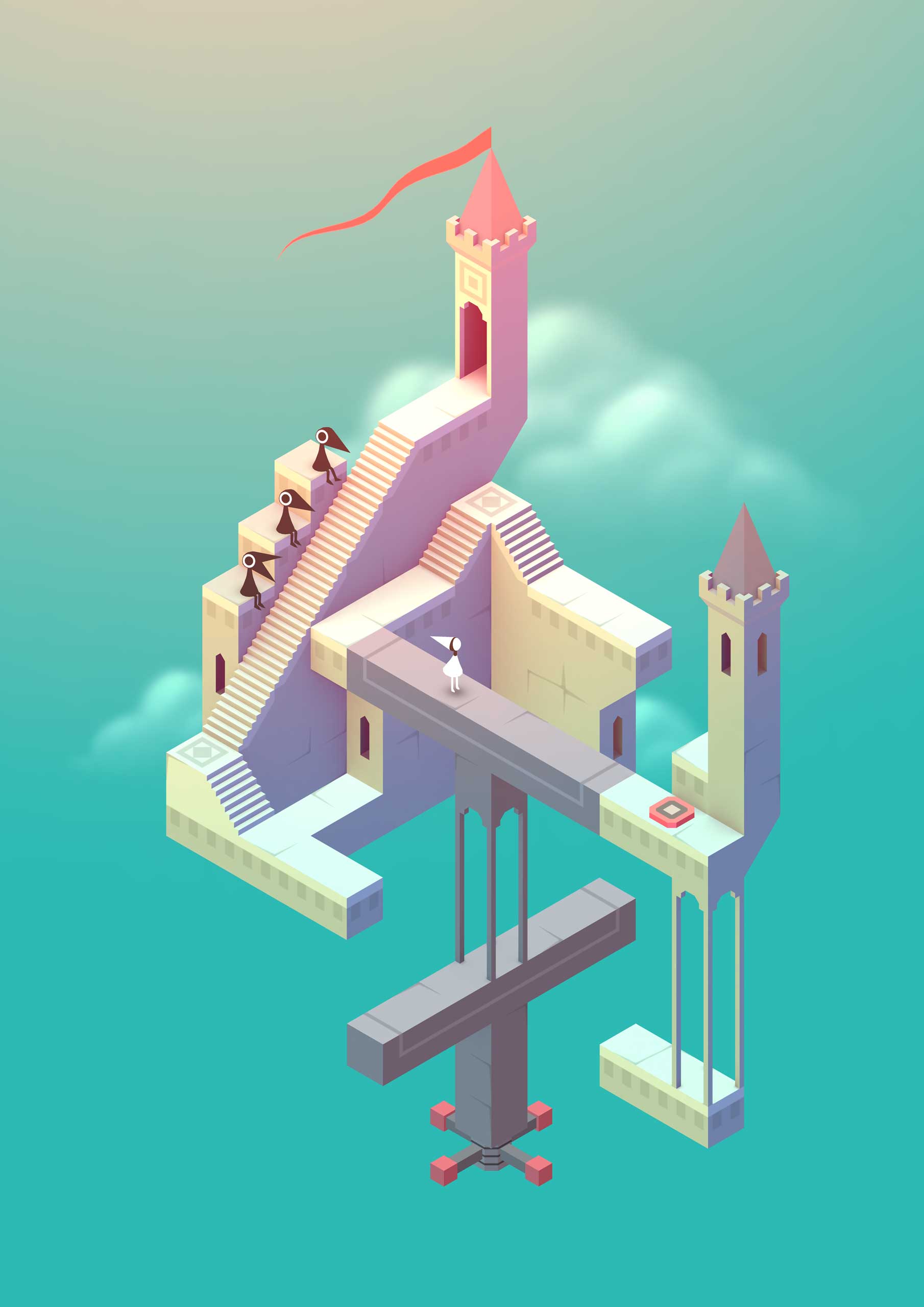

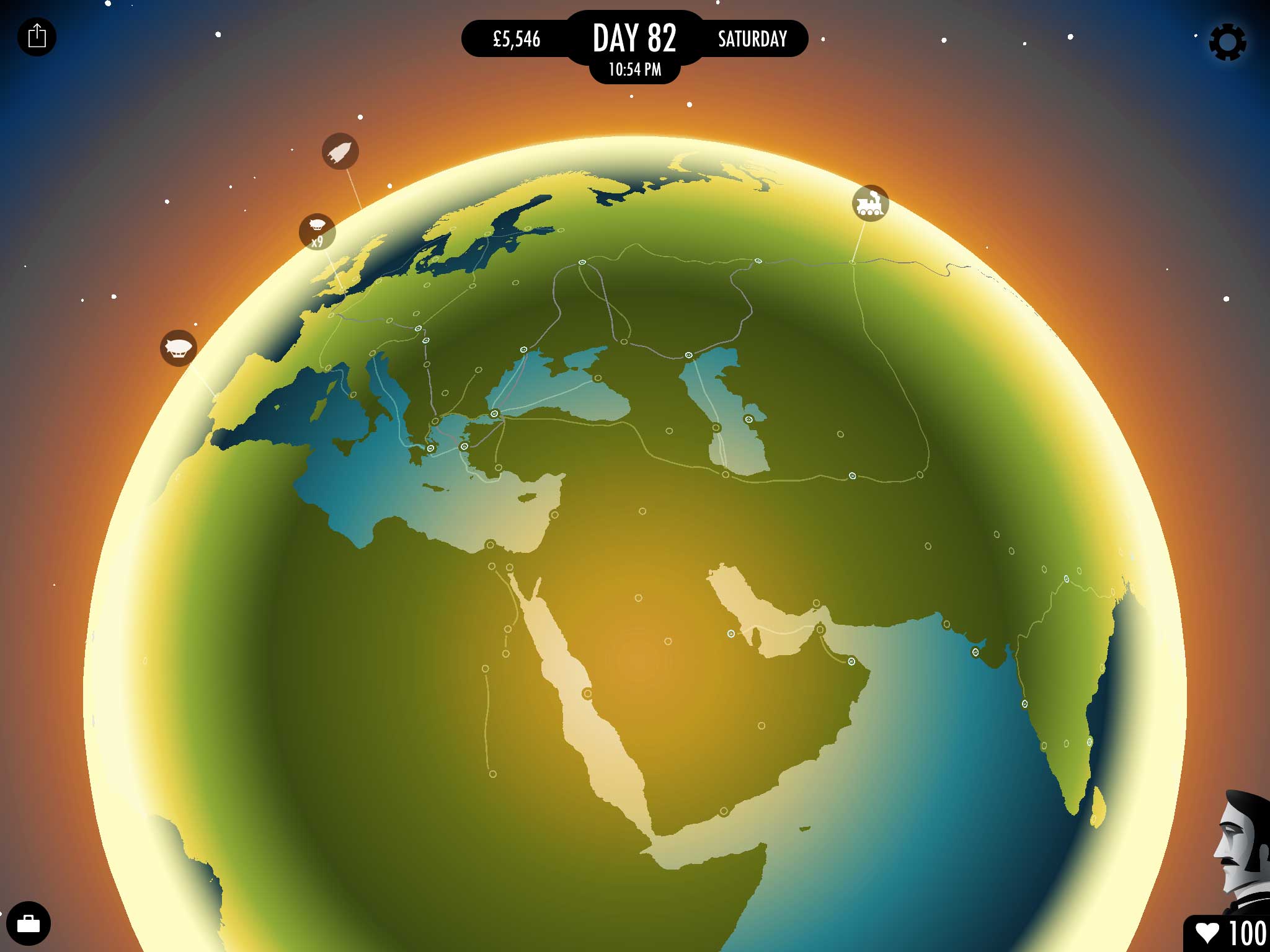

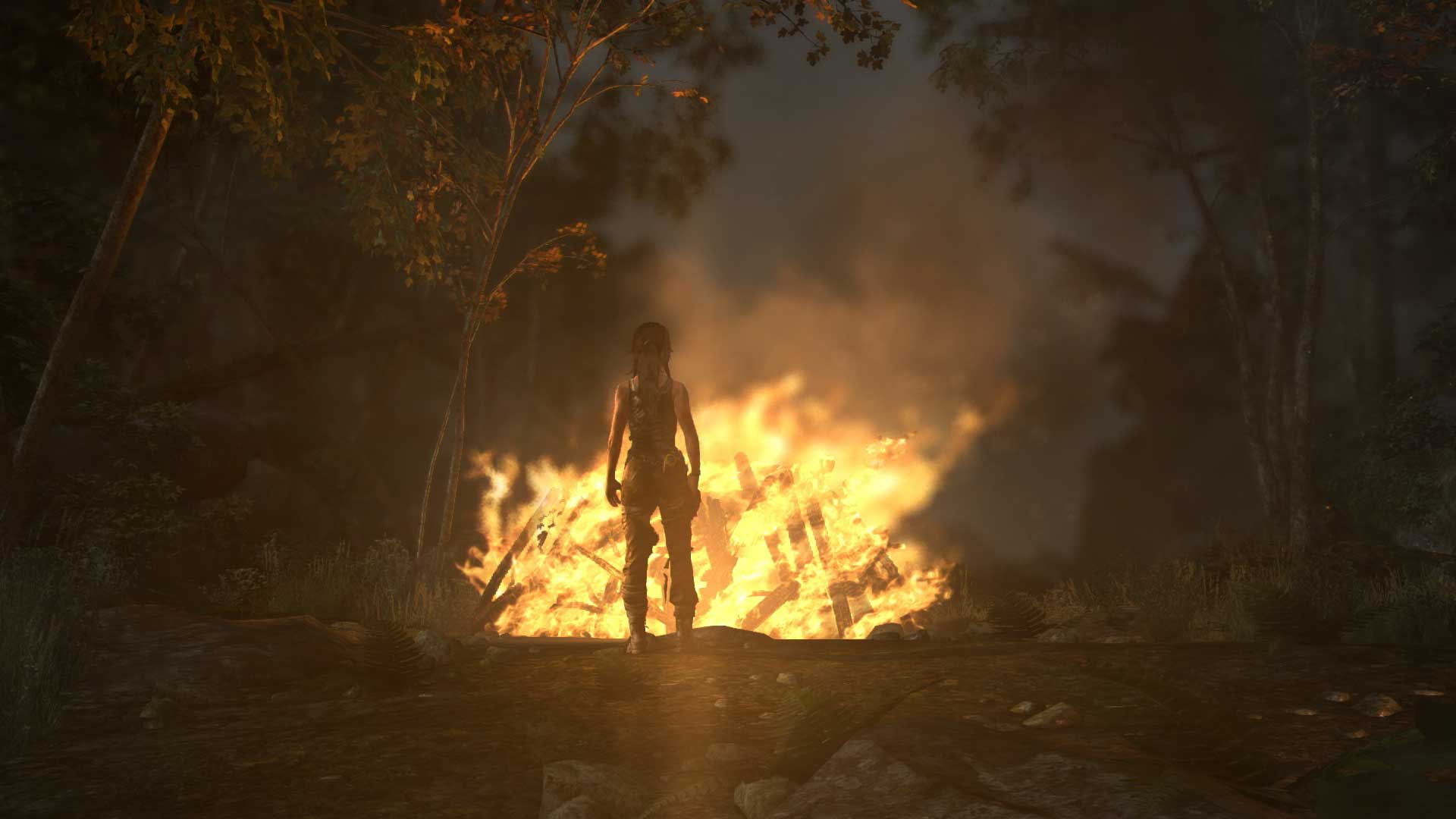

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

Internet-connectivity aside, the 3DS is like an iPhone on steroids. It’s kitted with two screens, one of which is touch-sensitive; dual cameras for use by games or for taking pictures; and Wii-like motion sensors. It displays images that appear three-dimensional without having the player use special 3-D glasses. The latest version, the prosaically named New Nintendo 3DS ($199), takes the concept further by using advanced eye-tracking techniques to improve the 3-D effect.

The company says the newest model is one example of how Nintendo will conduct itself going forward. Late into the development of the system, Nintendo met with a company that had the technology capable of improving its 3-D, which in previous versions had been knocked for not always working well. After previewing the technology, Miyamoto stunned his engineers. “He said, ‘Why aren’t we putting that in this system? If we don’t put this in, there’s no point in making the system,’” recalls Iwata.

In times past, Nintendo might not have upended its plans at the final hour to make complex technical changes. “I was personally asked many times by many engineers internally, ‘Are we really going to do this?’” says Iwata, who began his career as a programmer. “This is where my background in technology is quite helpful, because it means the engineers can’t trick me.”

The feature, dubbed “super-stable 3-D” by Nintendo’s marketing wing, is now seen as indispensable to the handheld’s overhaul. New Nintendo 3DS has rallied sales relatively late in the platform’s life cycle, giving the company a much-needed boost.

Next Phase

On balance, Nintendo’s methods have reaped more hits than misses. But the misses have been consistent and significant. Nintendo’s Virtual Boy, the company’s way-early shot at a virtual-reality gaming system in 1995, was a commercial disaster. The first “PlayStation” was supposed to be a Sony-manufactured add-on for Super Nintendo, but Sony and Nintendo couldn’t come to terms on a deal, spurring Sony to become a major competitor. And yet flights of fancy have ultimately proved to be Nintendo’s chief strength over the years. The Wii—with its motion-detecting controllers that had players swing invisible tennis rackets—seemed like a bizarre concept when it was unveiled in late 2006.

The comparatively weak response to the Wii U isn’t lost on Iwata. “Certainly I’m not satisfied with the current situation,” he says. “It may not be [people’s] first console of choice, but they recognize it as perhaps the best second console,” he adds. In truth, the Wii U may turn out to be a placeholder. “I think they’ve bought themselves time to figure out what that next monumental step forward is,” says Digital World Research analyst P.J. McNealy. Adds Yves Guillemot, CEO of games publisher Ubisoft: “The challenge for Nintendo now is to make sure their hardware continues to be convincing enough for people to buy.” Guillemot is confident the company can do that.

MORE Exclusive: Nintendo CEO Reveals Plans for Smartphones

Dan Adelman, a Nintendo executive from 2005 to 2014 who is now a games-industry consultant, says the firm “is already making the best games of any publisher out there.” Compared with those of other publishers, Nintendo’s games consistently earn top marks from critics. But Adelman says the company must continue to aggressively streamline its bureaucracy. “With Nintendo, I honestly can’t tell you what they’re going to do,” explains David D’Angelo, of Yacht Club Games, which released its title Shovel Knight for the company’s systems. “I could think about it all day, every day for a year, and it’ll still surprise me when it comes out, whatever wacky gameplay thing they think they should be pushing next.”

That leaves Nintendo rethinking its approach to the very industry it helped define. “I have never intended to dismiss the entertainment experiences that people are enjoying on smart devices or any other media,” Iwata says. “On the other hand, my understanding is that, on smart devices, the main demand is for very accessible games which smart device users can easily start and easily finish. These are not necessarily the characteristics that people demand from games for dedicated video game systems.”

As the company embarks on a strategy that straddles its traditional mode of innovation with the fast-changing world of mobile technology, there are likely to be more questions than answers. “We do have doubts [about] continuing to extend our business in the way that we have in the past,” admits Iwata. “We have doubts about whether or not people will continue to see those simple extensions of what we’ve done as new and surprising.” Fixing that will require entirely fresh ideas that can cut through the noise created by so many competing platforms. “If it takes a lot of explanation for people to understand your entertainment product,” says Iwata, “you’re doing something wrong.”

Read next: Exclusive: Nintendo CEO Reveals Plans for Smartphones

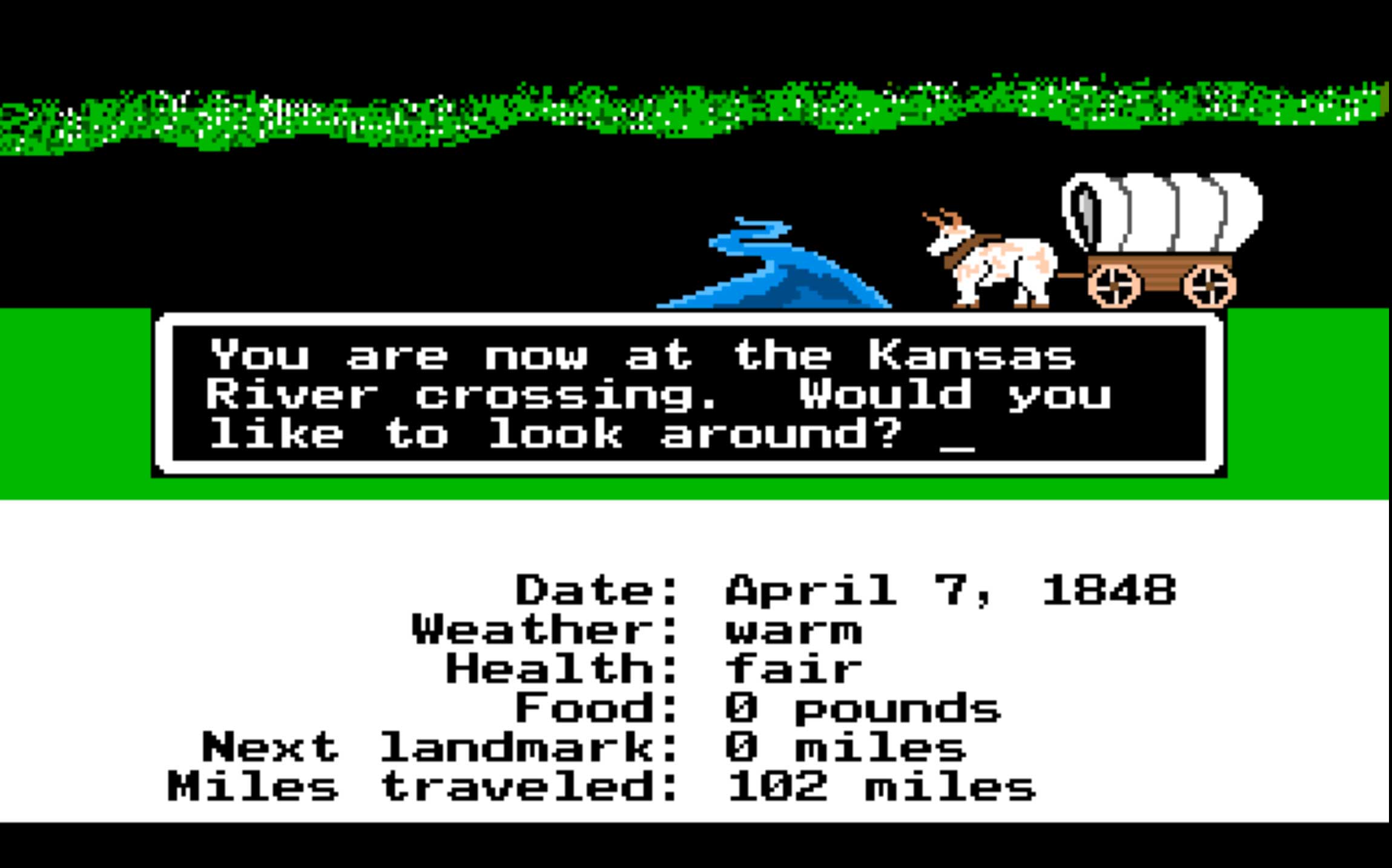

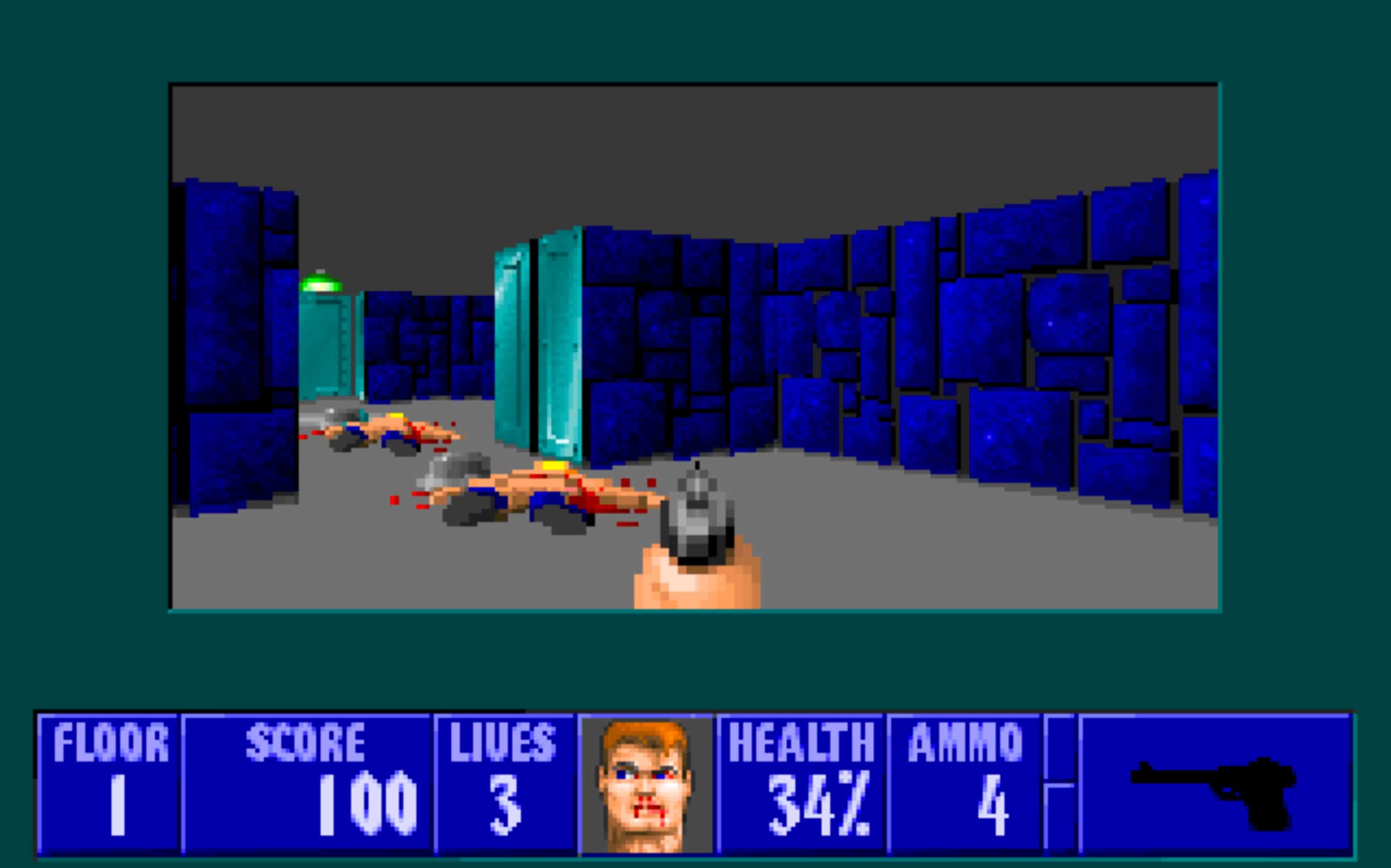

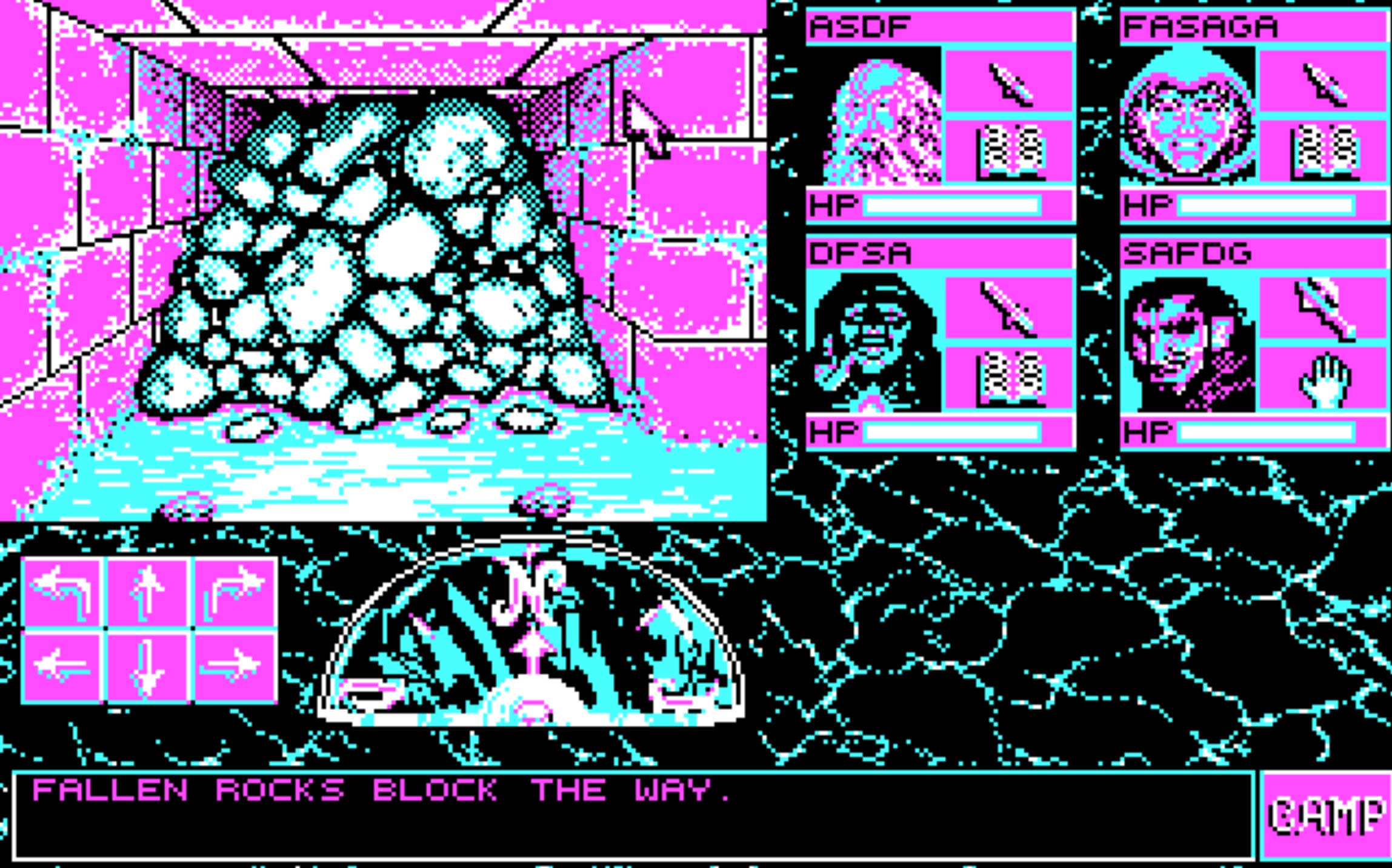

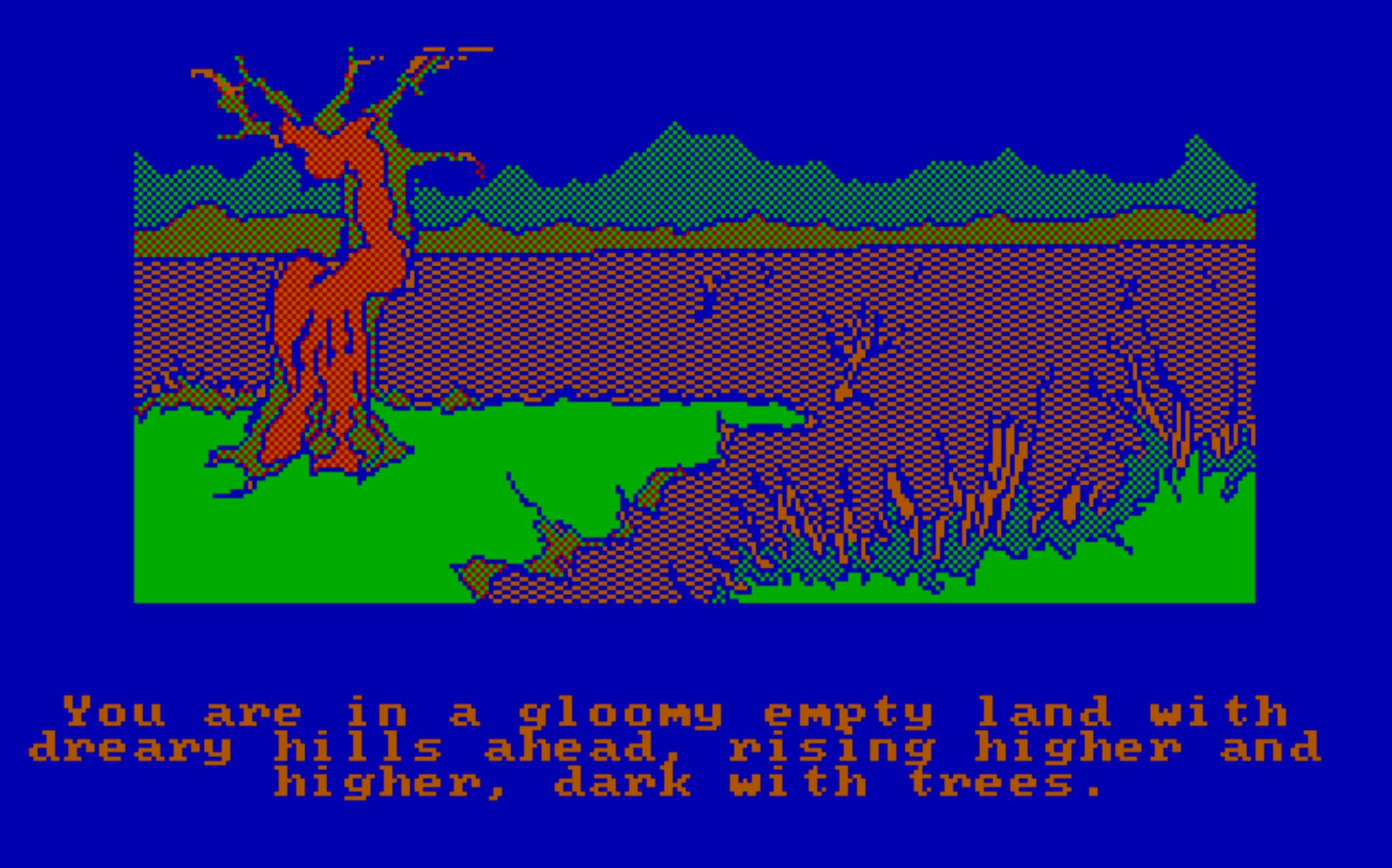

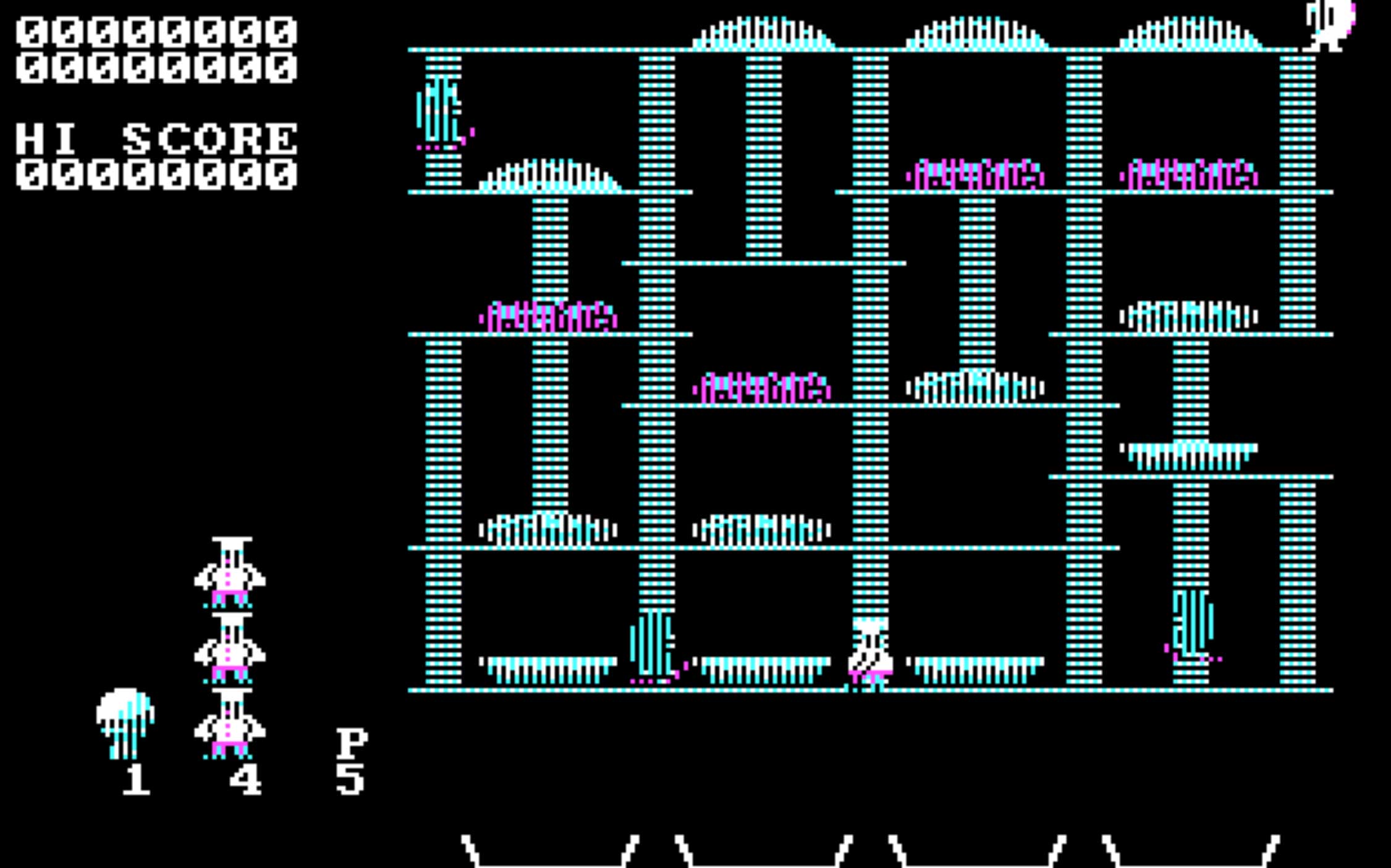

The 10 Best Classic PC Games You Can Play Right Now

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com