What are we doing here?

It’s Friday afternoon in Brooklyn, just days before the annual “Selection Sunday” that will decide the layout of the NCAA tournament. The Barclays Center, home of the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets, is hosting the conference tournament quarterfinals of the Atlantic 10, a hoop-centric group of schools whose core geographical imprint stretches from Philadelphia, through Washington, D.C. down to Richmond, Virginia, while hitting a few places in the midwest: Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Dayton. Yet the Atlantic 10 hosts its conference tournament in New York City, home to Fordham University—one of the league’s northern outliers and worst basketball teams.

Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and the University of Richmond, two schools separated by five miles in the Virginia capital, are playing a tight, tough game, which VCU will eventually win, 70-67. But the whole thing still feels a bit out of place. The Atlantic 10 moved its tournament to Brooklyn back in 2013 because, more than anything, college athletic conferences have become marketing entities. Let’s bring the show to the big city, baby, no matter the convenience for the “student-athletes,” whose time spent traveling extra miles could be spent, you know, studying.

This rivalry game sparked some electricity. Fans of VCU, which made a surprising run to the Final Four back in 2011, travel well, and as VCU finishes off the Spiders, the place is loud and moderately rocking. Still, the building is only a little more than a third full, according to the official attendance figures. Empty seats dot prime areas behind the basket. Most of the fans are wearing yellow (for VCU) or red (for Richmond), but very few locals seem to be there. The Big Apple hasn’t exactly caught A-10 fever.

Which comes as no shock. Across the country, people seem to be falling out of love with college basketball. Attendance for Division I men’s games has fallen for seven straight seasons, according to the Associated Press. TV ratings for CBS and ESPN are down.

A well-documented drop in scoring, which is near historically low levels, has been blamed for college basketball’s struggles. Ugly play has certainly contributed. Controlling coaches drain the fun and flow out of the game. Players are stronger—and more physical, which tends to hurt, more than help, offense. Technology has made scouting an opponent’s tendencies easier. When you know what your foe is about to do, he’s easier to defend.

These trends have surely contributed to college basketball’s struggles. So have some forces beyond the sport’s control. More than ever, Americans want appointment television, whether it’s a must-see football game or even an international soccer game we can all chirp about on Twitter, or a favorite show on the DVR. We have so many entertainment options: Our investment in a two-hour regular season college basketball game better pay off. Too often, it doesn’t.

In football, the regular season games really matter. In baseball, a fraction of the teams make the post-season, so even the early April games have something at stake. In college basketball, if teams struggle in the regular season, they can earn a March Madness spot by doing well in a conference tournament. Does any one regular season game really matter that much?

True, you can say the same thing about NBA regular season games. But if you like basketball, and can choose between watching the best players in the world in the NBA, or a bunch of college kids throwing up bricks and college coaches calling a million timeouts, and calling for a million fouls at the end of close games… it’s an easy call.

When pitted against football, college hoops is almost helpless. College football is a juggernaut, and college basketball starts its season in mid-November—just as the playoff and bowl chases are coming down the stretch. Into December and through the Super Bowl, the NFL is going strong. Even the NFL off-season overshadows college hoops. This past week, major free agent moves—and in particular, coach Chip Kelly’s casino gambling with the future of the Philadelphia Eagles—stole tons of attention from conference basketball tournaments.

College basketball is in danger of becoming a one-month sport, capturing buzz only during March Madness. The sport’s relevance problem even sparked Pac-12 deputy commissioner Jamie Zaninovich to propose on SI.com that the start of the regular season be pushed back to mid-December, and the Final Four to take place in early May—to help college basketball escape football’s shadow.

Officials can tinker with the game. But some of the optics of this week’s conference tournaments also suggest that, because schools have been chasing the lushest revenue streams, the sport has also just lost its way. On Thursday night at Madison Square Garden in New York City, for example, Butler, from Indianapolis, and Xavier, from Cincinnati, met in the quarterfinals of the Big East tournament. Why are schools from two Midwestern cities, connected by I-74 through Indiana, playing in New York? As part of something with “East” in the name?

All the conference reshuffling of the past few years destroyed many regional rivalries. Out of this rubble rose a new entity called American Athletic Conference (AAC). ESPN showed highlights from an exciting AAC quarterfinal game between East Carolina and the University of Central Florida that went into overtime. East Carolina won 81-80. The game was played in Hartford, Conn. On TV, the stands looked empty.

College hoops is still thriving in many places. And as we gear up for Sunday night’s selection show, a drab regular season will be forgotten. We’ll fill out our March Madness brackets, root for Cinderella, see if Kentucky can become the first team to finish undefeated in almost 40 years. It’ll be a blast.

But the question is still worth asking: What are we doing here?

Read next: The Case for Sports Gambling in America

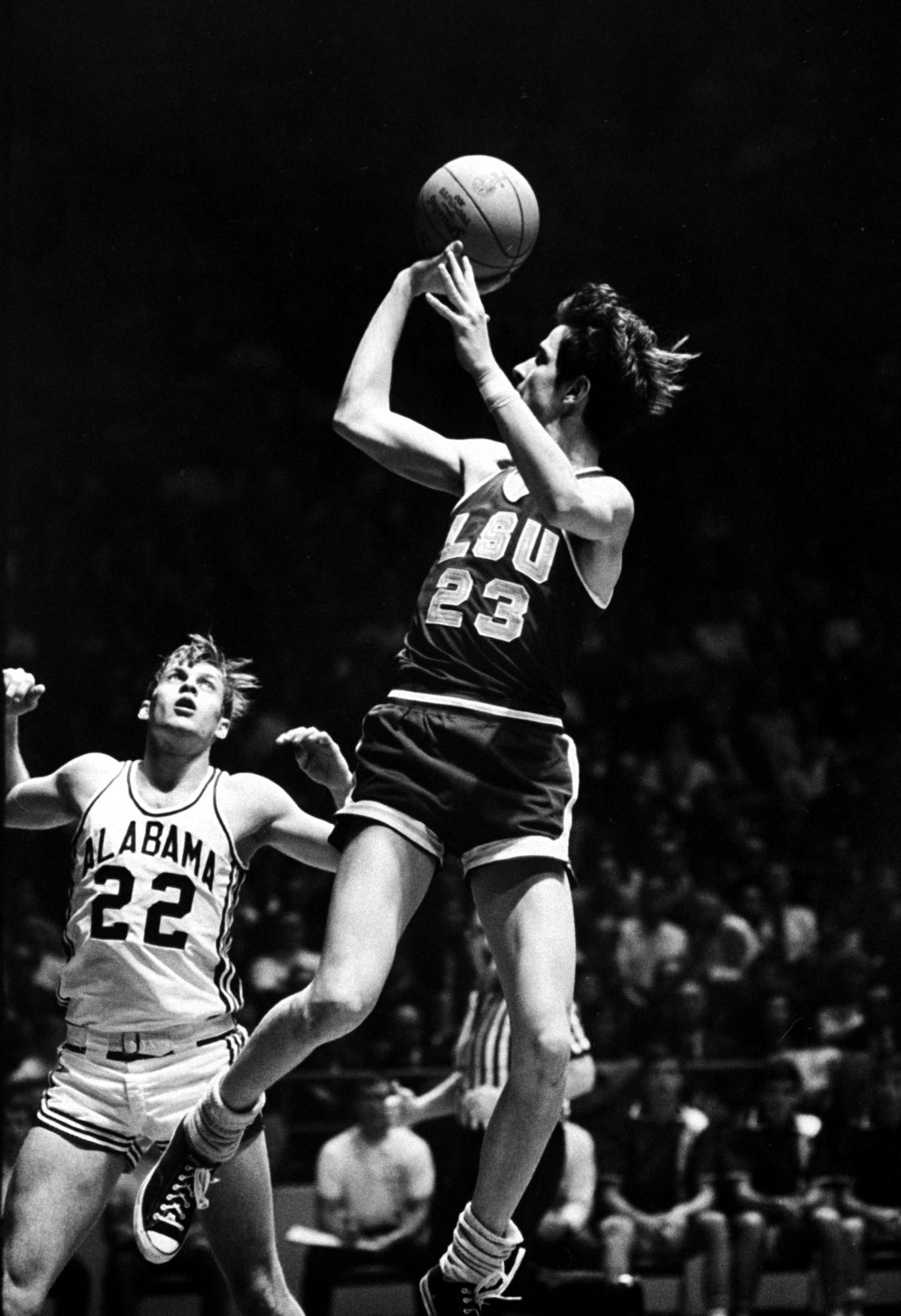

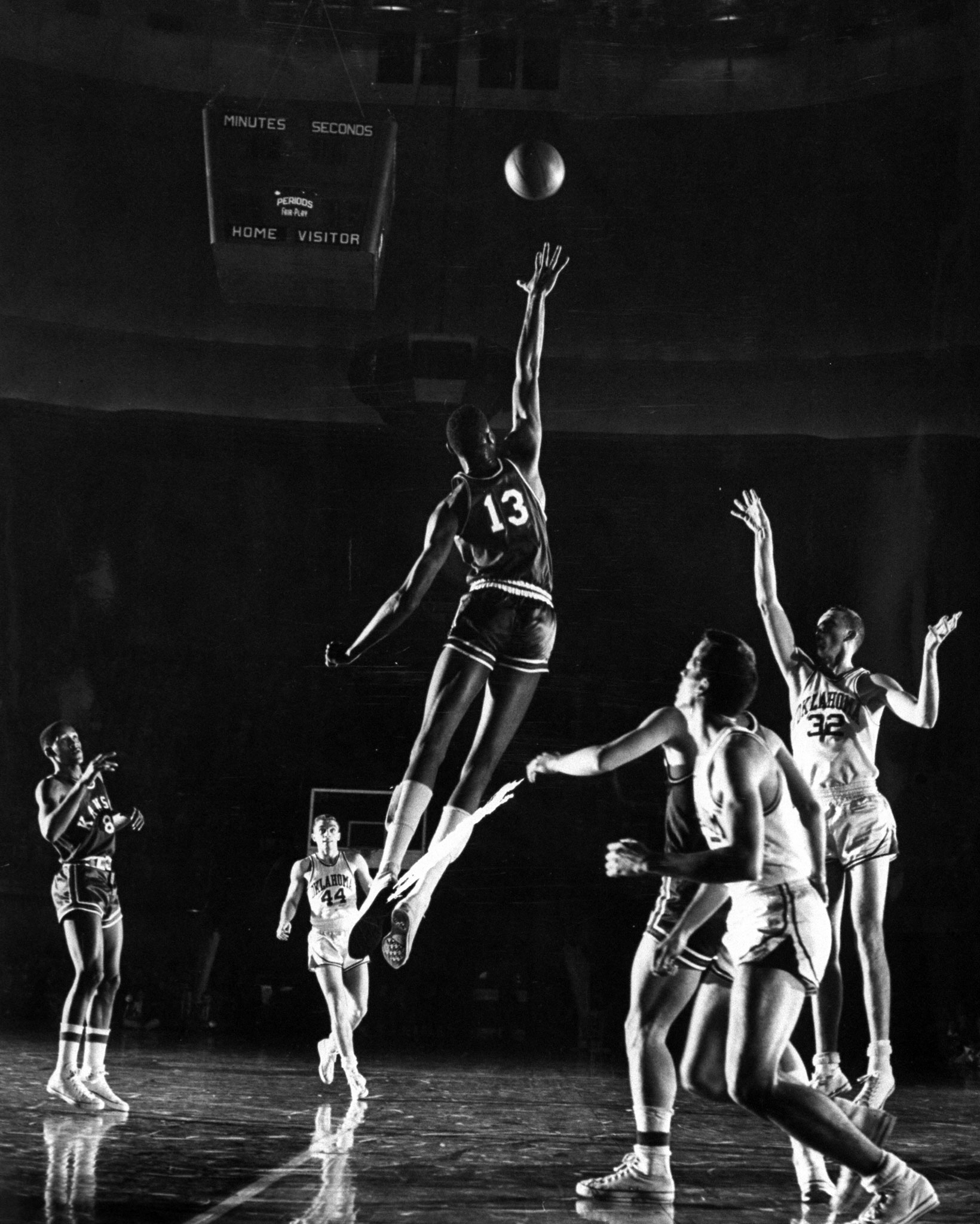

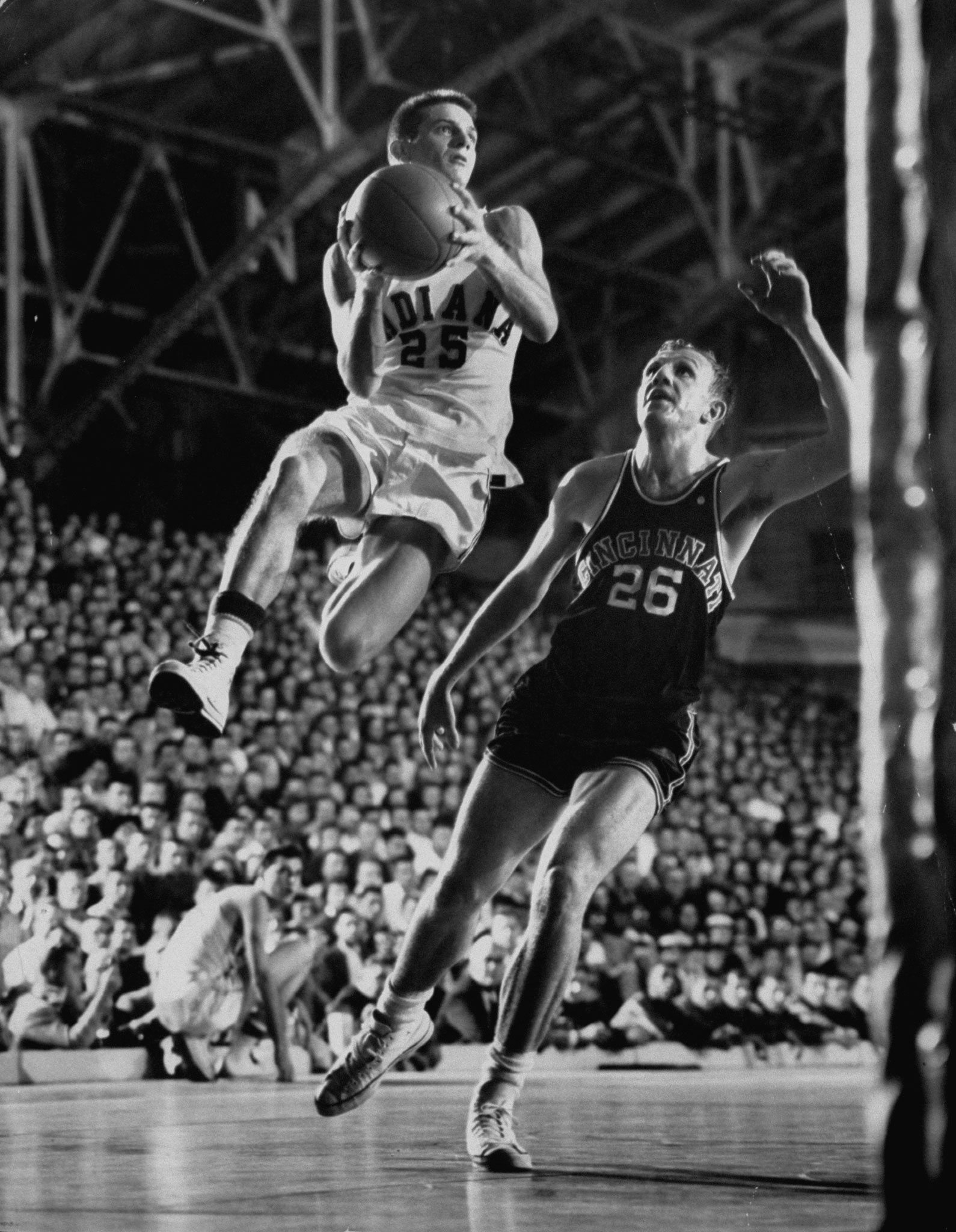

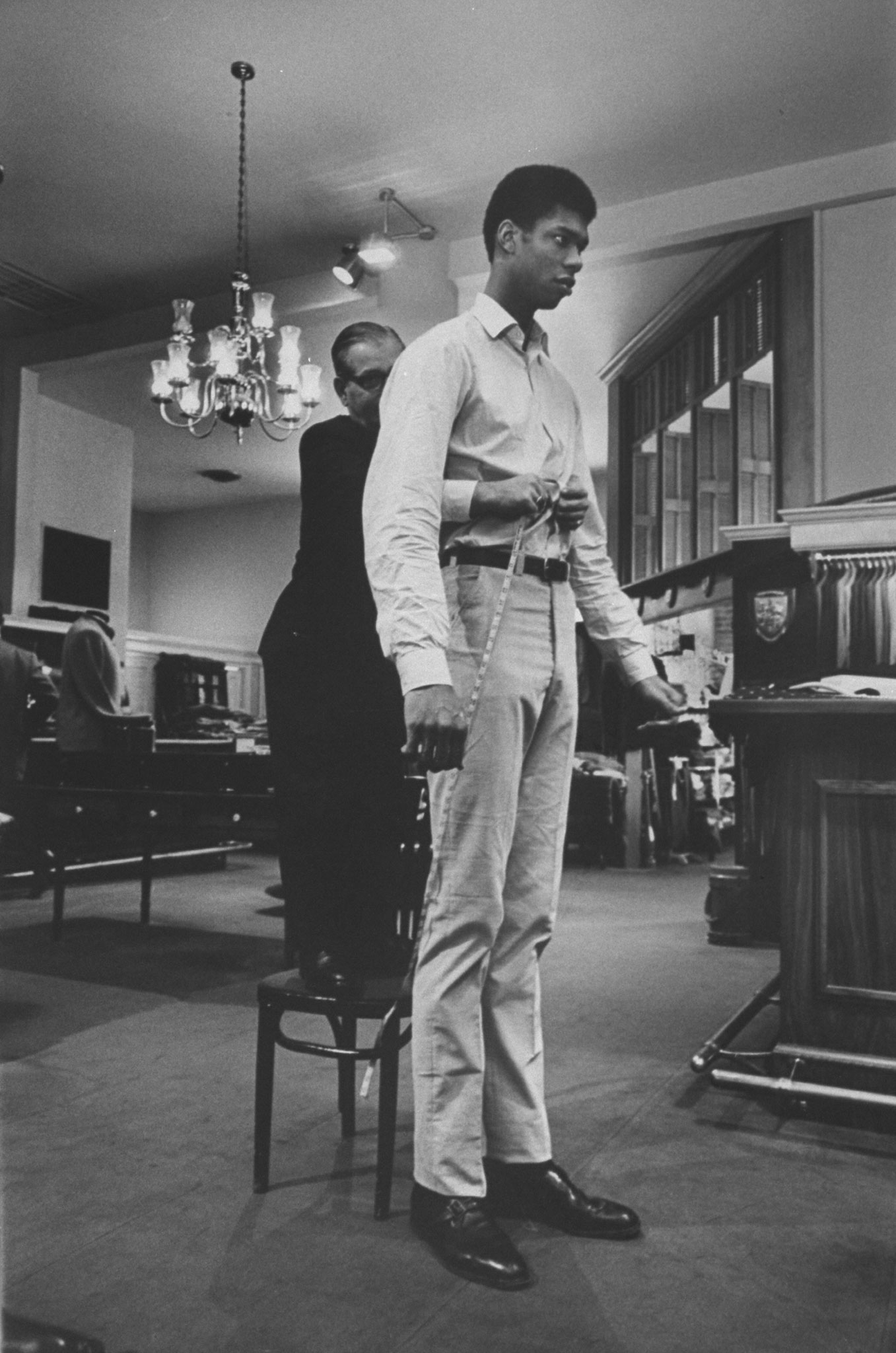

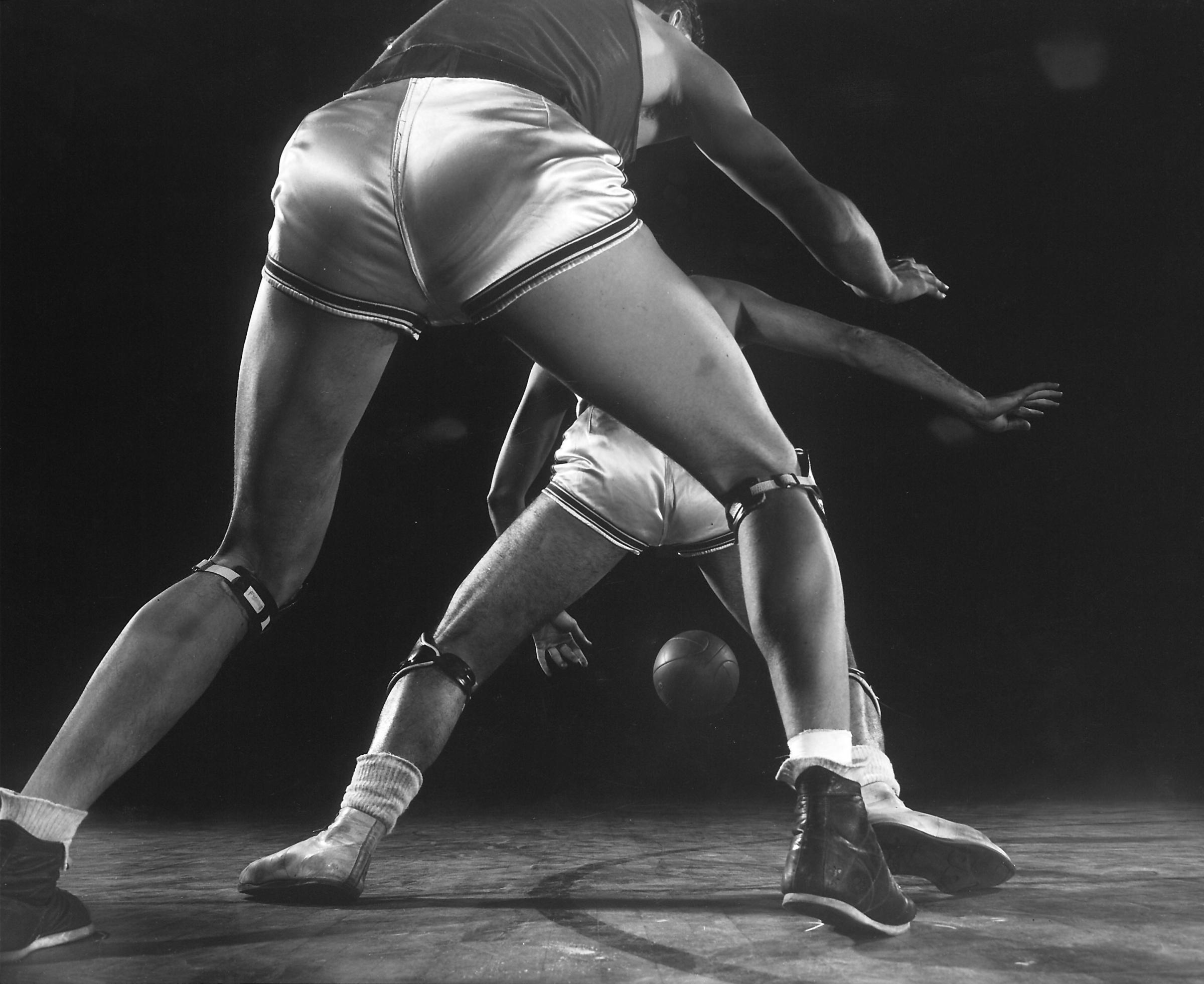

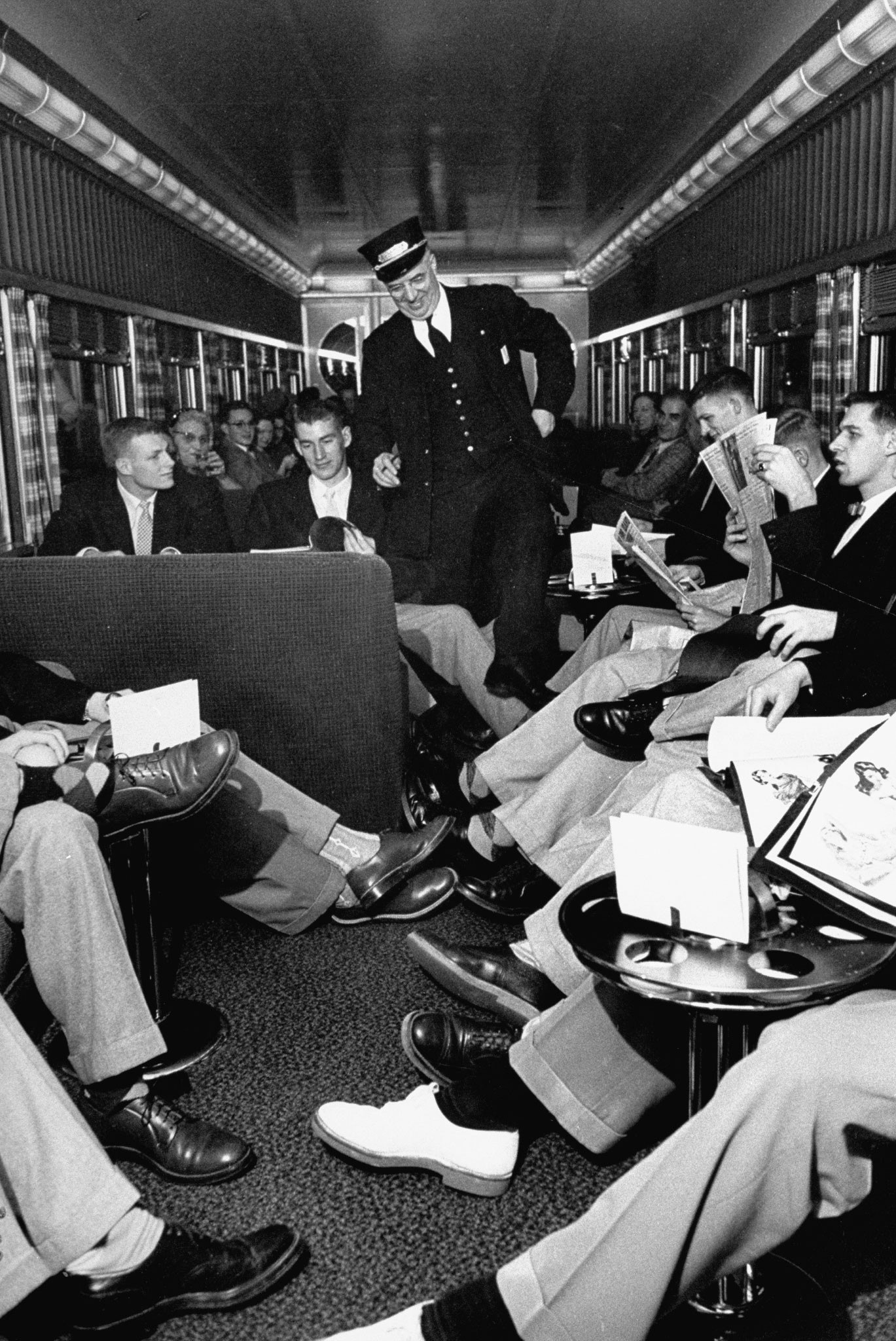

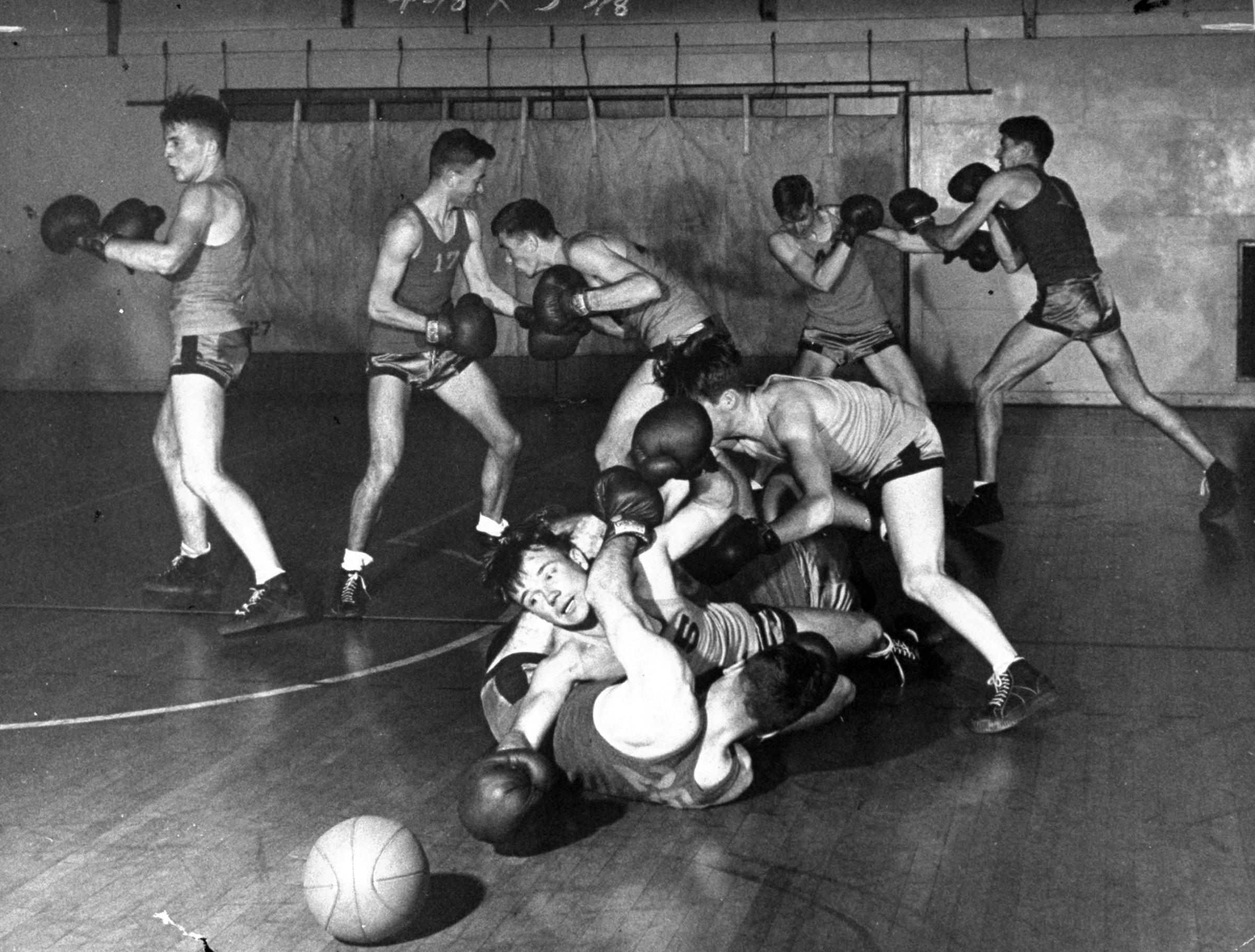

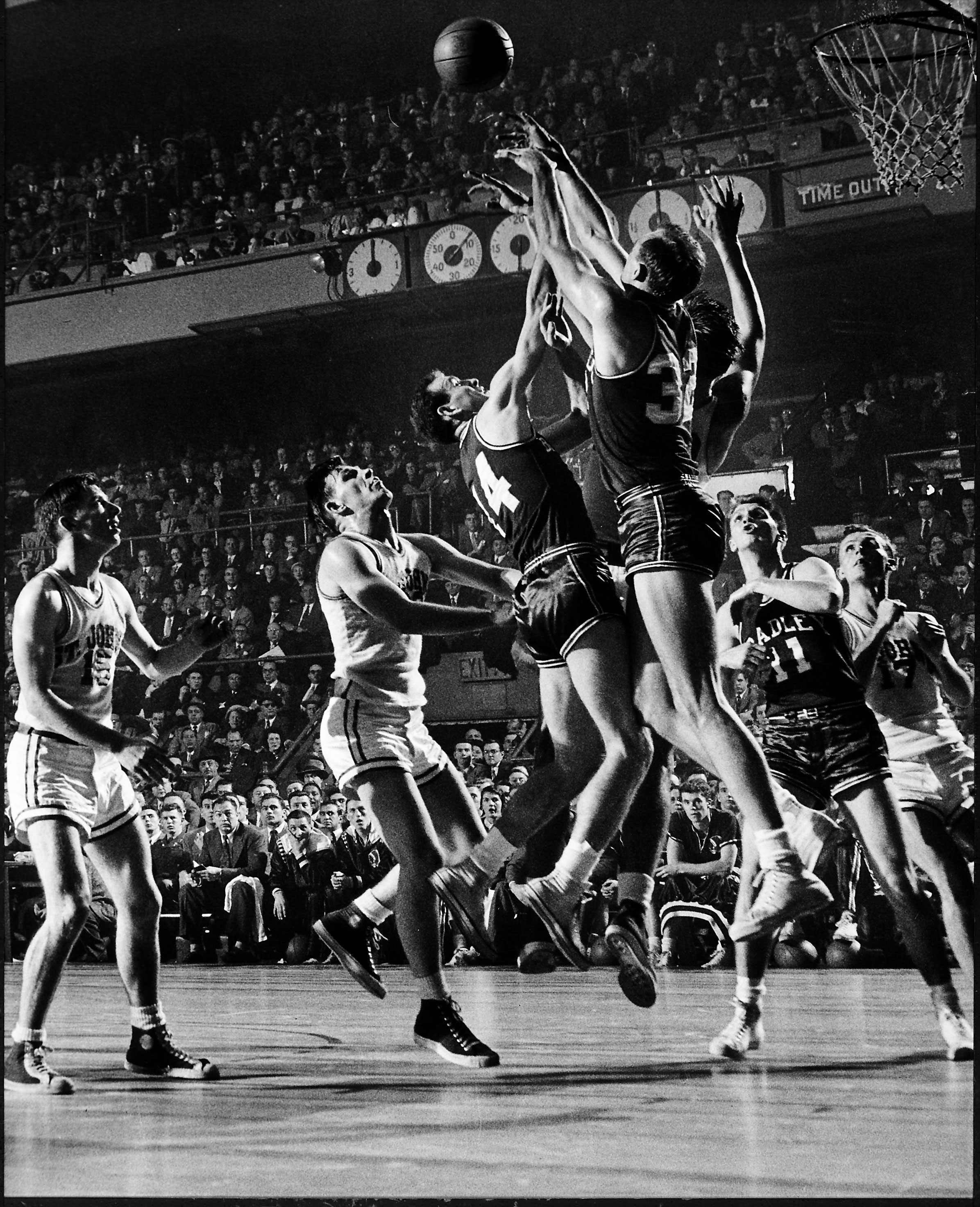

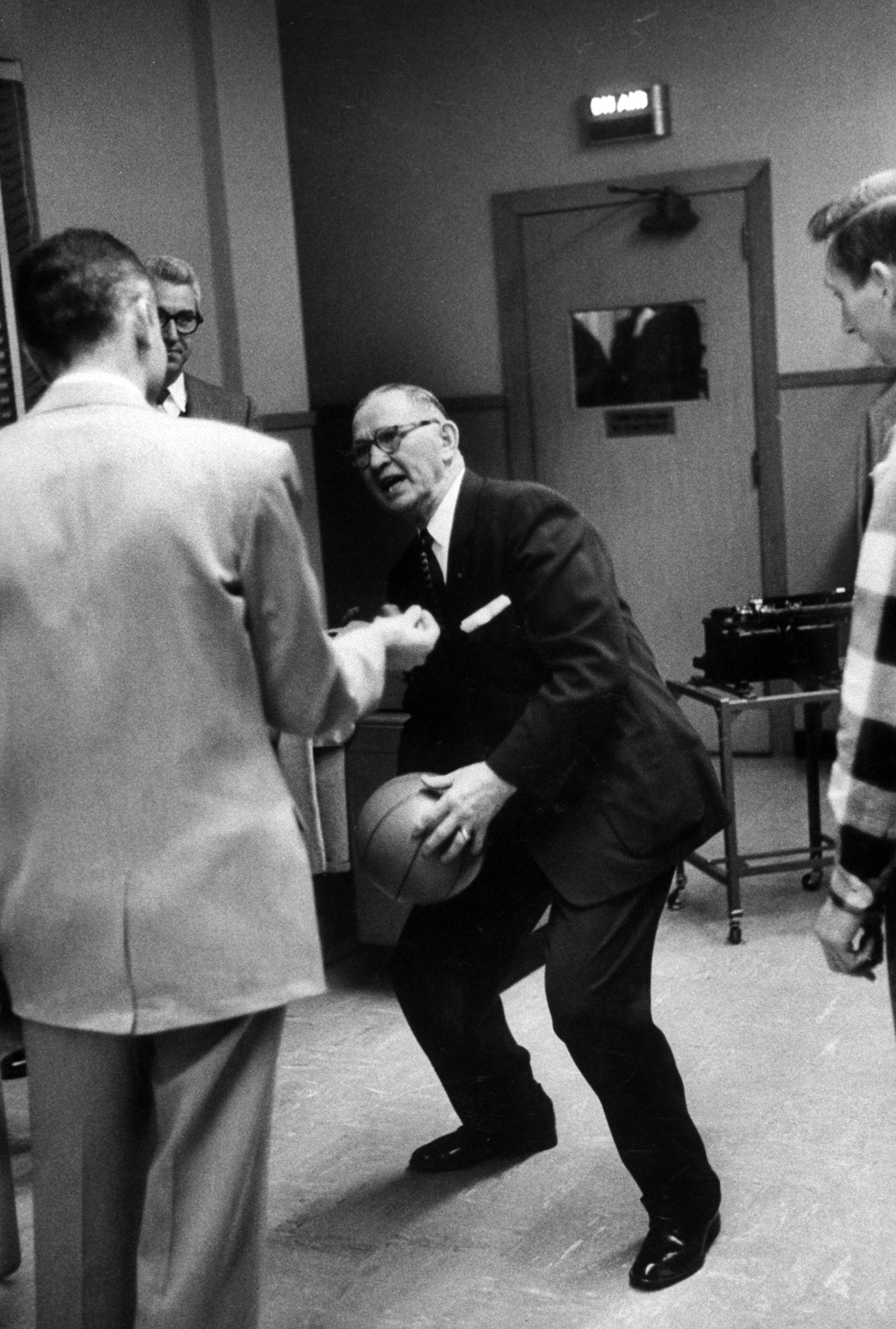

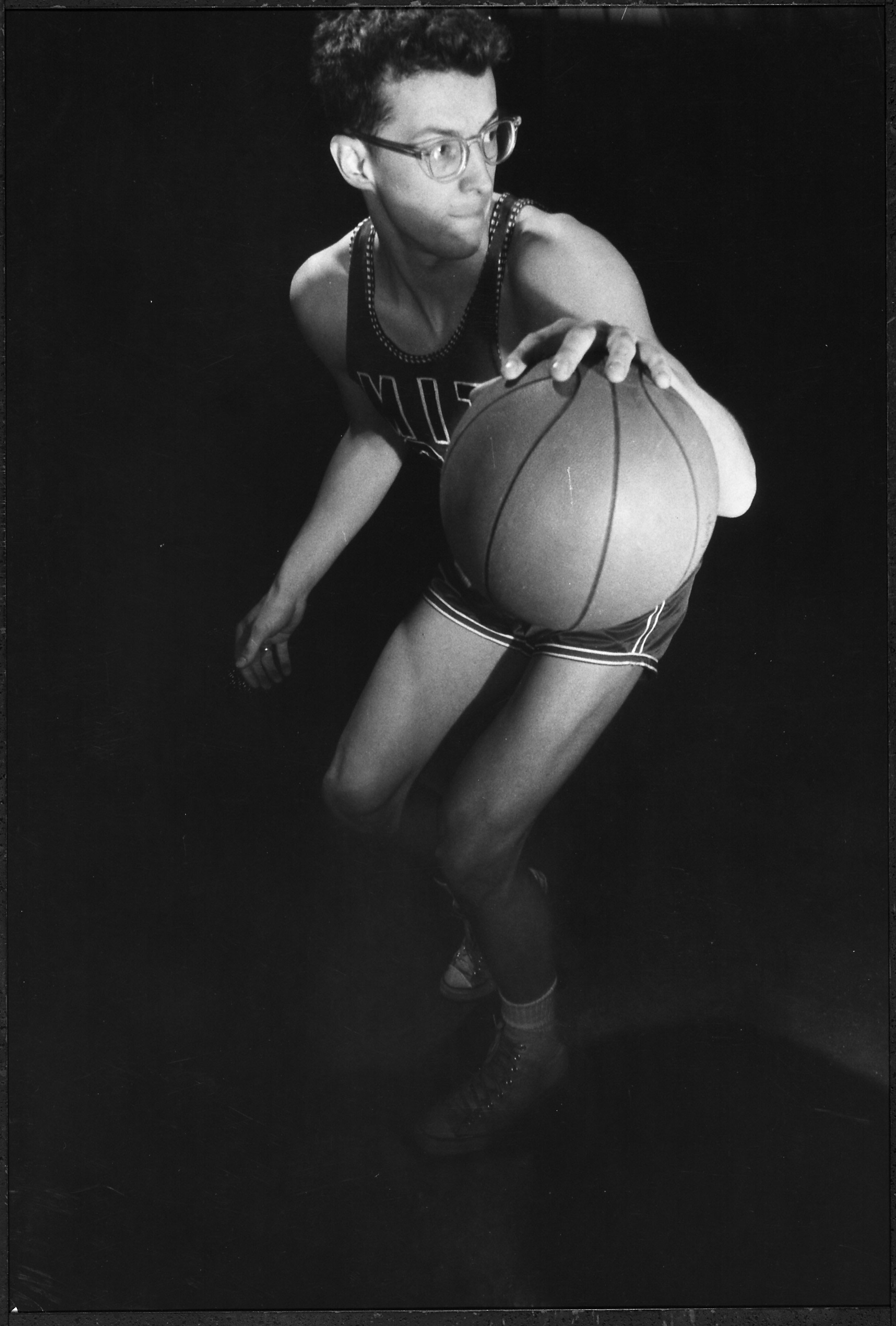

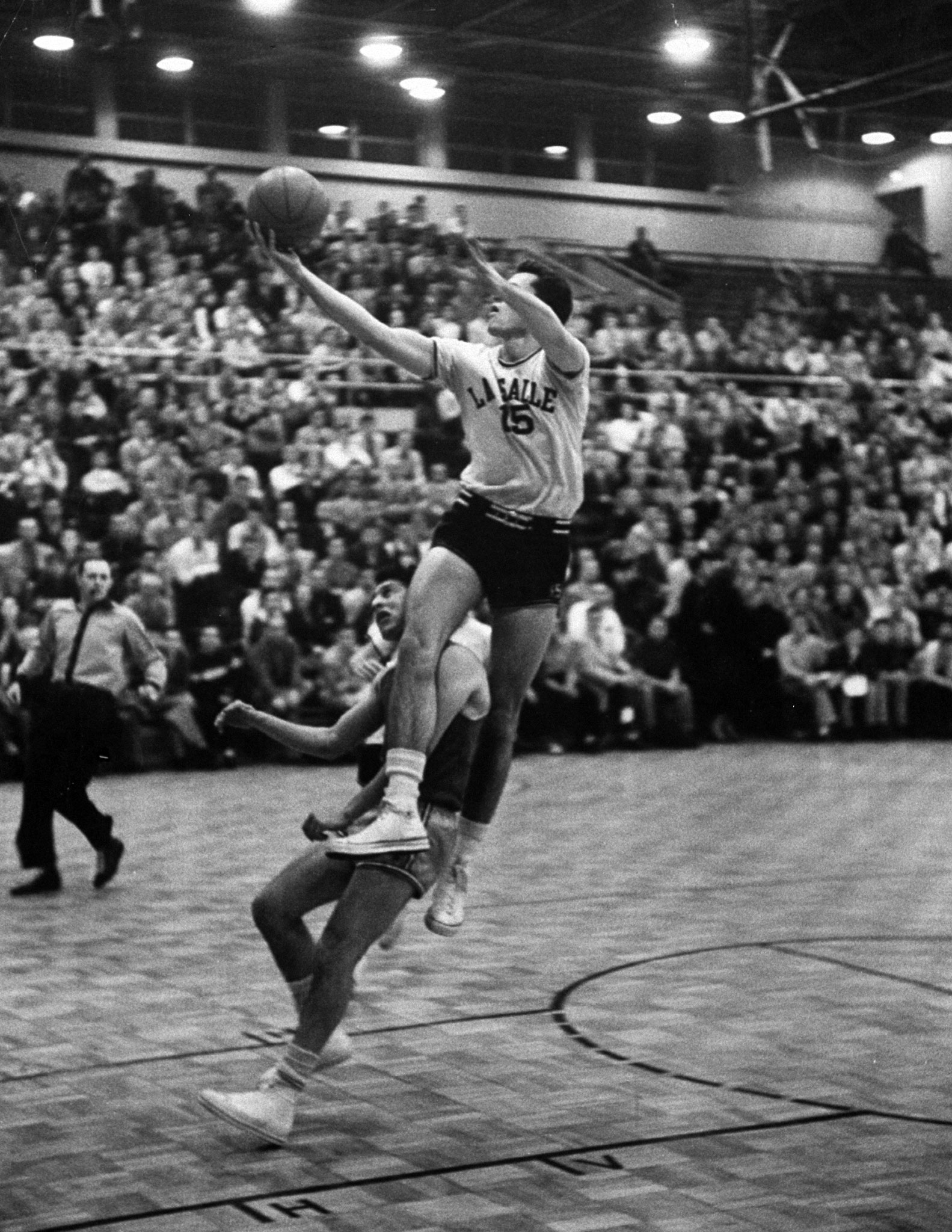

LIFE Shoots Old-School College Hoops

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com