On Nov. 10, 2014, a motorcycle accident left Ian Willms’ father paralyzed and laying in a South African hospital bed by himself. The Canadian photographer put his life on hold to be by his bedside. On Nov. 28, Willms took to Instagram and posted a black-and-white image of his hand holding his father’s, the first photograph in what has become Willms’ most personal photography project yet. Last month, on TIME LightBox, Willms discussed the impetus behind his photographs. Now, he tells us what he learned from the experience.

Two years ago, my dad picked me up at a Southwest Florida airport at 4am. I was coming in from an assignment and could have taken a taxi, but he insisted on coming to collect me. It wasn’t the first time he’d done something like this. It was his way of showing that he was proud of me. On the way to his house, we sat together in a Denny’s until the horizon began to glow with a faint blue haze. I looked at him over black coffee and fried eggs and he made a proposal: the two of us should go on an epic motorcycle trip across South America.

A burning desire for adventure was something that him and I had in common, but we had never done a major journey together. It seemed like the right thing to do at a time when we were in the process of healing our relationship. We started to make a plan to ride from Columbia to Uruguay in March 2015. I was looking forward to what I knew would be a cathartic moment for us, but tragedy struck and we ended up on a very different road.

In an instant, his motorcycle accident last November changed both our lives forever. When I finally laid eyes upon his battered, comatose body in South Africa, I discovered what it meant to grieve a living man. The strong, independent person that I knew as my father was gone. I wanted to just break down right there and feel that loss, but there were many urgent matters at hand. He was laying in a private hospital and the bills needed to paid immediately. I signed on as the manager of my father’s care and began the process of emptying his bank accounts against enormous debts that grew by the hour. I was completely alone in a place that I knew nothing about, my father was unconscious and no one knew if he would survive.

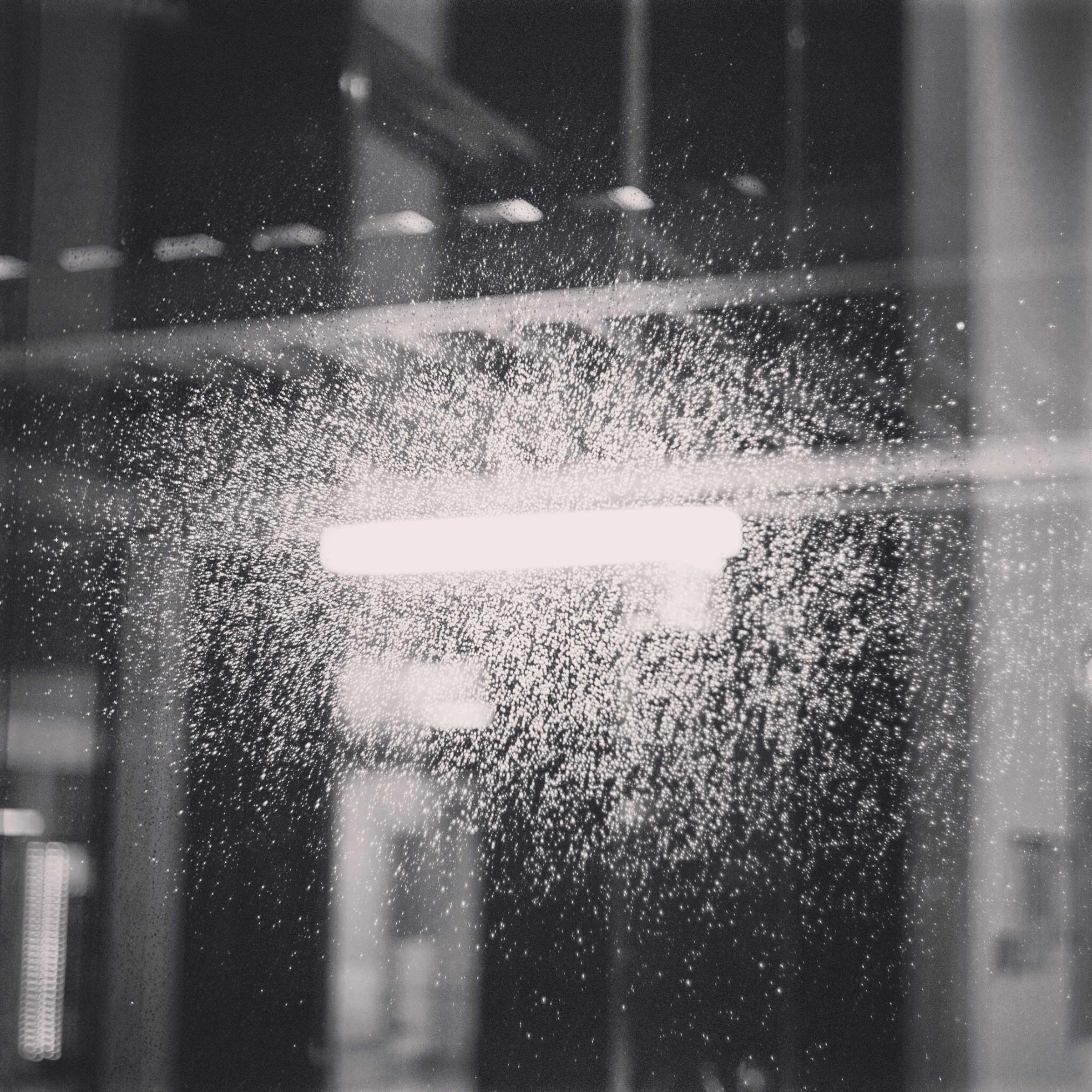

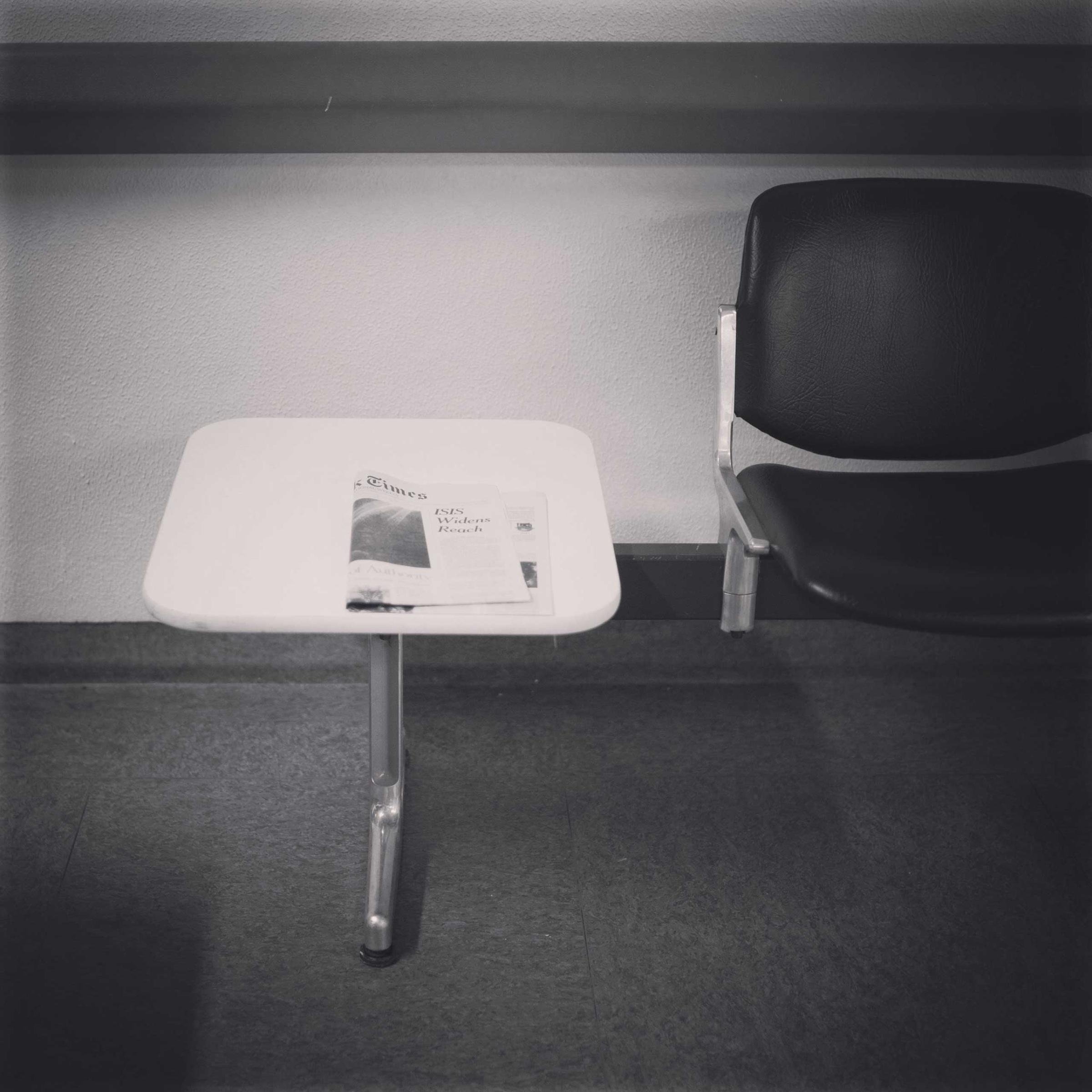

As the days turned to weeks, I began to feel like a soldier. I would march between my rented room and the hospital for the three designated visiting hours each day. In-between those times, I would argue with bankers and insurance companies, pay medical bills and struggle to manage all the other loose ends in my father’s life. My days were completely dominated by my father’s care. It felt like him and I were both in prison, except he was being held in solitary confinement. I was desperate for a way to express what I was feeling. With my father’s blessing, I began photographing the details of our daily routine and publishing them to Instagram.

The day after spending Christmas with my father and sister in the hospital, I sent an e-mail to my aunt in Canada. It closed with the following:

“It is getting harder for me as the weeks wear on. I feel like I don’t even remember the rest of my life anymore. Like this is all I’ve ever known. It’s just such an all-consuming situation. […] This has been the worst experience of my life, but as my dad told me the other day, it helps you grow up.”

The Intensive Care Unit where my father stayed was very busy. Doctors and nurses ran around, trying desperately to be in two places at once. Many lives came to an end in that room during my father’s stay, but not his. He went into and out of two medically induced comas. The drugs made it difficult for him to distinguish his nightmares from reality. The experience broke him down to the emotional capacity of a scared child. Against all odds, he survived to be repatriated to Germany in early January.

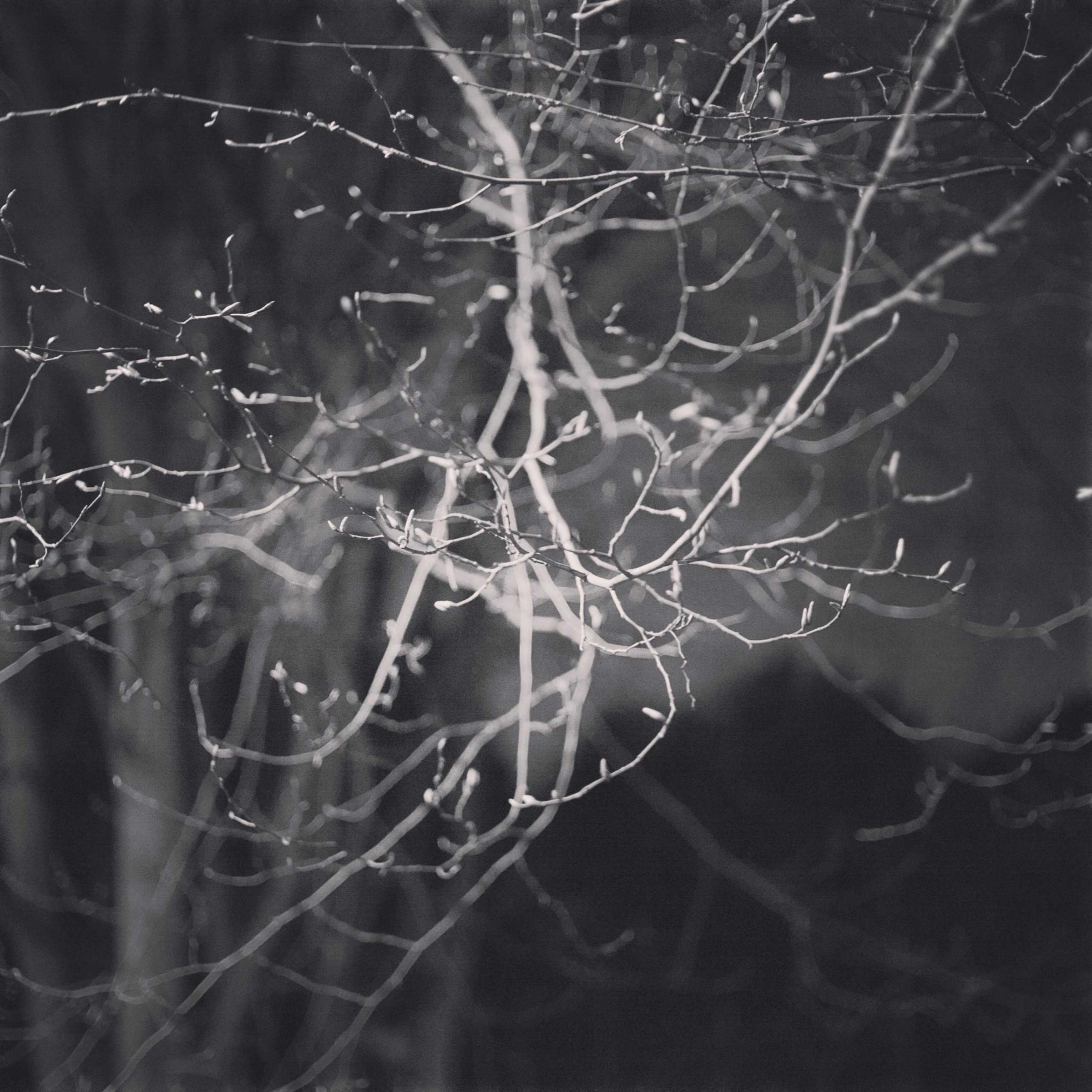

When we reached Cologne, I stayed with my 93-year-old grandmother. The hospital was further away now, so I was only able to visit my father once a day. The daily responsibilities that used to occupy my days were mostly shifted to other people who spoke German. With that extra time on my hands, the weight of my own pain and isolation finally began to manifest itself. I was tired at all hours of the day, yet unable to sleep. My skin broke out into stress rashes. I was irritable and became angry over minor details. My father began to comment on how ragged I looked. He blamed himself for my burnout. I took a photograph of myself in the hospital elevator after leaving his room that night.

When I began making these pictures in South Africa, I was showing a lot of what I was dealing with. There were photos of the hospital, my father and the administrative side of his care. Once we transferred to Germany, my own emotional state became the primary subject of the work. A dark weight grew in my mind with each passing day. The more distance I had from my father’s pain, the more intensely I felt it inside me.

By that time, the photographs had grown into something much more than a visual diary. They had become a pivotal moment for my craft. As a documentary photographer, I was used to expressing the pain of others through my work. Never before had I been so emotionally connected to the subject matter that I was photographing. I did not concern myself with the purpose or meaning behind my photographs. I was acting solely on emotional impulse. If I felt it, I shot it and published it. There was no editor, curator, art director to answer to, except myself. The audience was anyone who cared to watch.

I left Germany on Feb. 28. Being in Toronto seems like what I would expect a soldier feel after returning home from war. I’m always thinking there’s some urgent matter for me to attend to, but I’m supposed to be resting. Since I left, my father has been mostly alone. Before the accident, he always acted tough and independent. Now when we talk, he tells me that he misses me and wishes that I would return. Those conversations leave me feeling sick with guilt. I gave everything I could to help him and he’s still so far from being okay. Everyday, I think about him laying there in that bed; his prison cell. It’s the same haunting image that made me rush to his side in the first place. Now I feel like I’ve left him behind.

My dad and I will never take that motorcycle tour to Uruguay. He’s paralyzed for life and I’ll probably never touch a bike again. We’ve talked about that trip a couple times since his accident. The conversation usually brings him to tears. I remind him that he and I have just shared the most incredible adventure of all: the journey from death to life. My dad has told me a few times that I’m the only reason he’s still living. It’s amazing to think that I saved his life. Especially when I consider how angry I used to be with him when I was younger. I take comfort in knowing that I was motivated through all this by my unconditional love for him. Above everything else, this is the greatest gift I could ever ask for.

Ian Willms is a Canadian photographer and a member of the Boreal Collective. This interview is the second part of a multi-part series on Willms’ We Shall See project. Read part one here.

Olivier Laurent, who edited this photo essay, is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com