Robin Thicke’s long period of career misfortune continues. Yesterday, a jury ruled that, due to similarities between Thicke’s hit “Blurred Lines” and Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up,” the R&B singer and producer Pharrell Williams must pay nearly $7.4 million to the late Gaye’s children. For once, though, Thicke’s bad luck affects someone other than himself. It’s easy to see the judgment as a worrisome sign that authorship in music is about to get a lot more narrowly defined.

After all, Thicke and Williams didn’t interpolate the actual recording of Gaye’s track; their ripping-off of Gaye, if one agrees with the court that they did indeed rip him off, is a question of having been influenced too much. But without influences and borrowing from one another, there’s practically no popular music at all. Nearly all of contemporary music, from Taylor Swift’s ’80s pastiche on “Style” to Meghan Trainor’s faux-doo-wop stylings on “All About That Bass” to every act that tries to sound like Avicii — they’re all reaching back to music from the recent or distant past, if only because there are only so many ways to truly innovate. Even in Williams’ own back catalog, listeners have noted similarities to other songs: Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” bears some resemblance to “Criminal World,” from David Bowie’s Let Dance; both were produced by Nile Rodgers. It’s unsurprising, given the tendency of producers to stick with a particular style that works for them: Producers from Dr. Luke to Ryan Tedder to Williams have been criticized for leaning on a particular sonic template, a critique that ends up exposing just how few ways there are to get to a hit song.

Musical phrasing and structure, unlike the structure of thoughts in a paragraph or the design of a dress, is particularly hard to pick apart on plagiaristic grounds; there are so many elements of a song working together, and to untangle them is to get frustratingly semantic. The Gaye lawyers had to call in a musicologist, who spoke somewhat airily about the “constellation” of elements that “Blurred Lines” took from “Got to Give It Up.” It’s undeniable that the pair of songs sound similar in some aspects, but the differences (in vocal performance, for instance) are striking, too. To what degree should Thicke and Williams be granted leeway for being part of a genre, and an art form, with a tradition of trading on influence?

It says nothing about the legitimacy of the Gaye children’s claim to wonder whether enterprising performers and entertainment-industry lawyers will be listening very carefully to every song that hits number one on the charts in the coming months and years. Madonna, for instance, has publicly criticized Lady Gaga for using an “Express Yourself”-inflected chord progression on her song “Born This Way.” Should that similarity, which comes close to a simple matter of opinion, be legally actionable?

Plagiarism is a very serious violation for how it misrepresents the author or artist as having had creative impulses not his own. “Blurred Lines” is an original composition that, in some of its particulars, resembles specific aspects of another song. But that takes away nothing from its originality — except, that is, in a court of law.

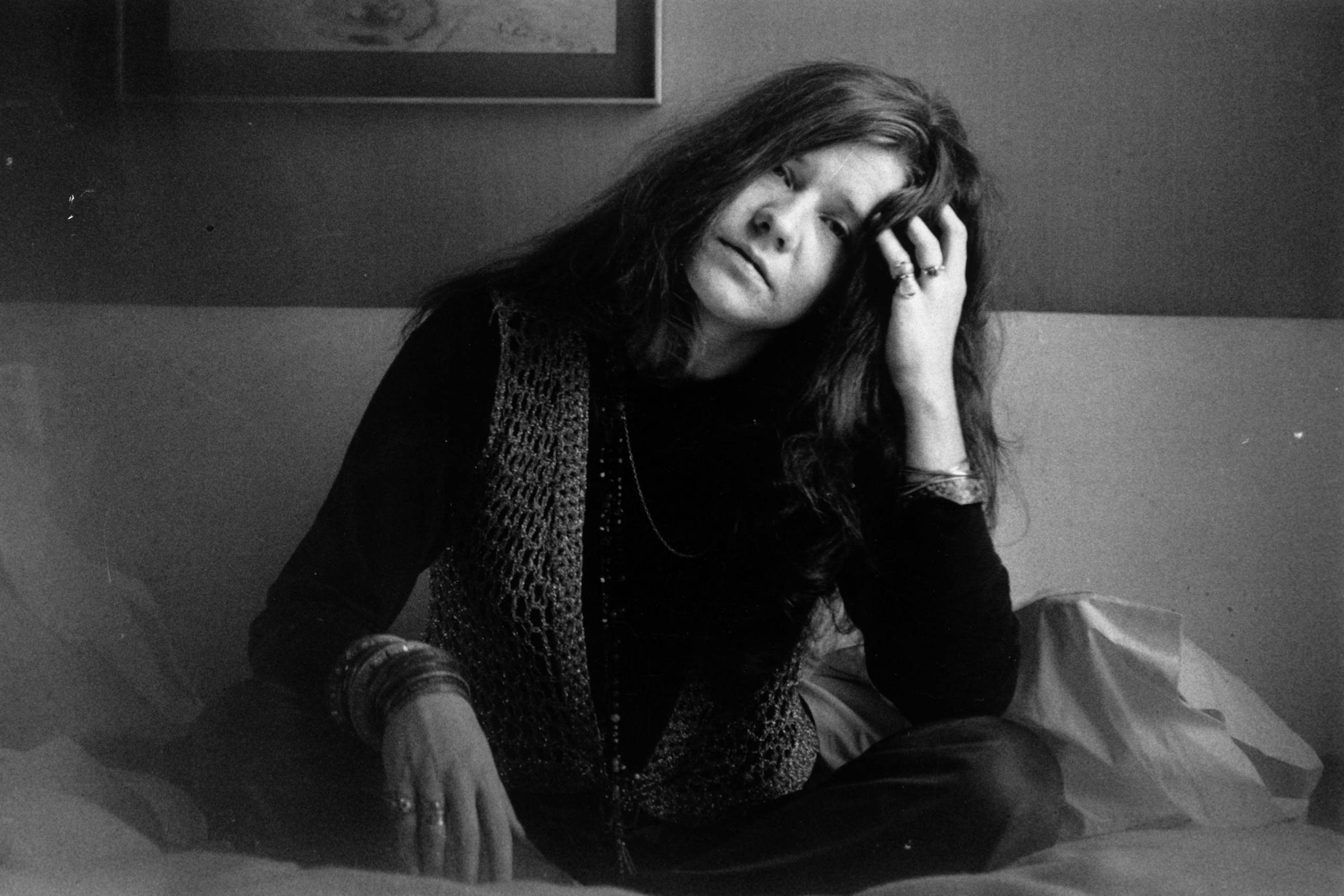

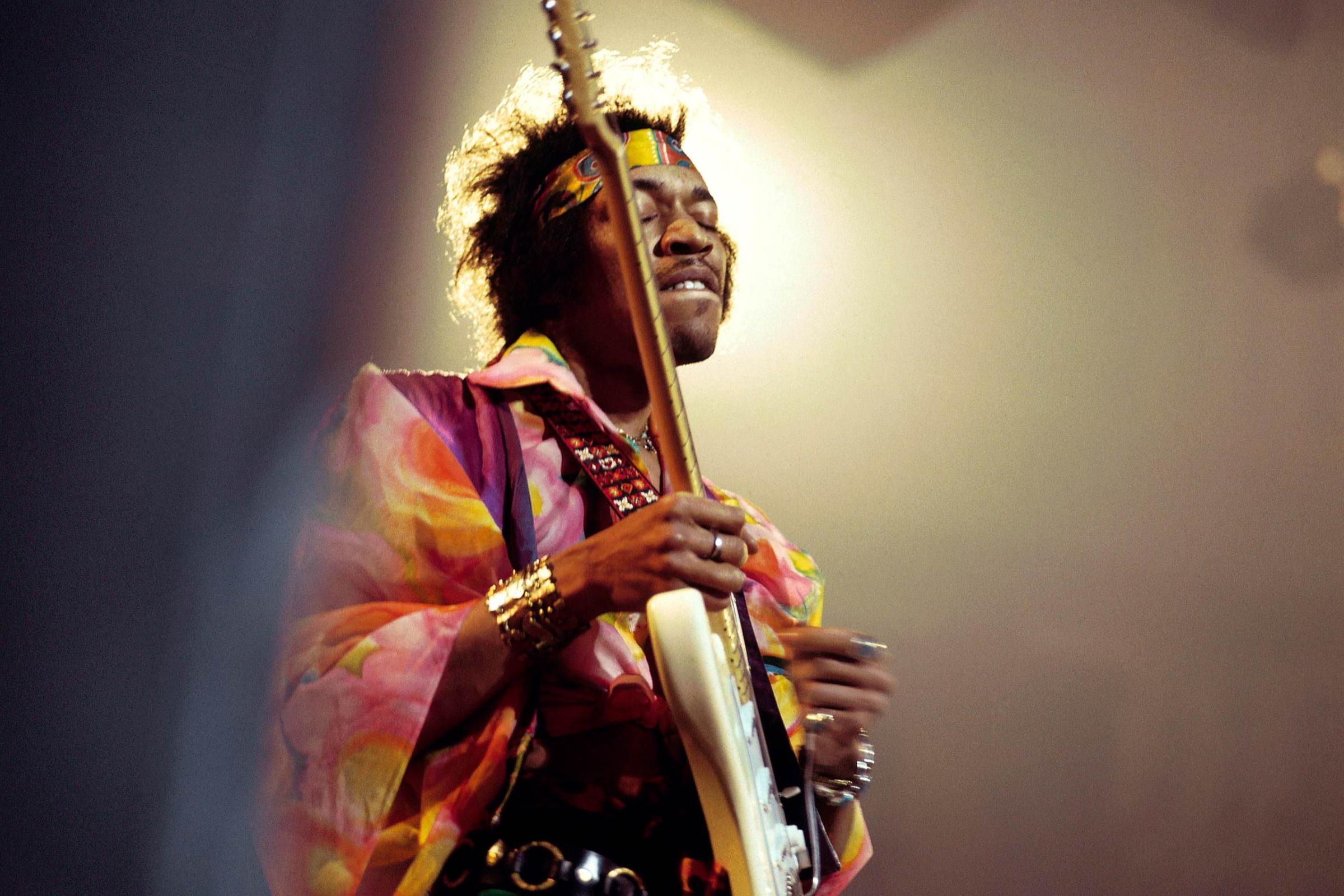

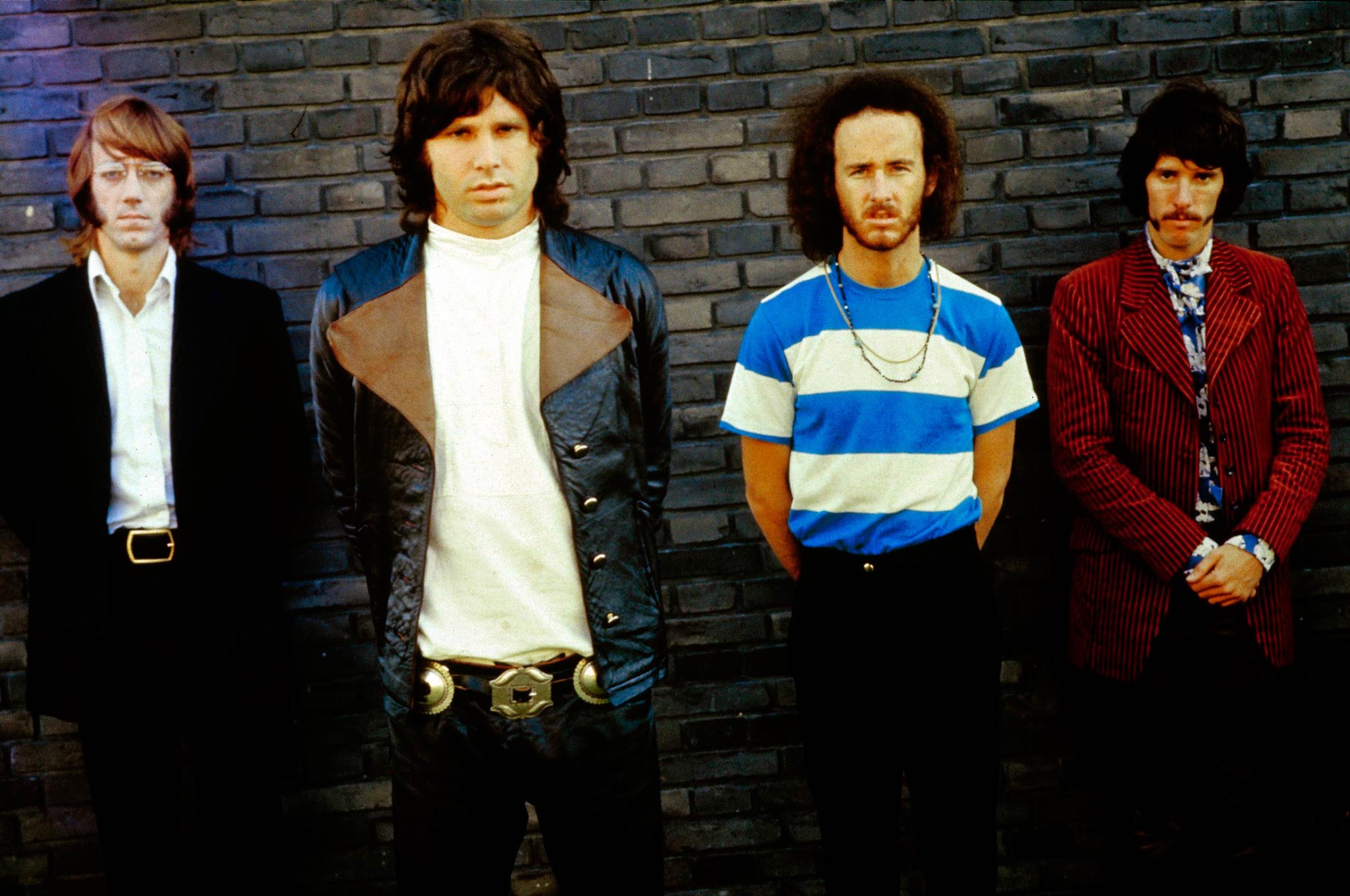

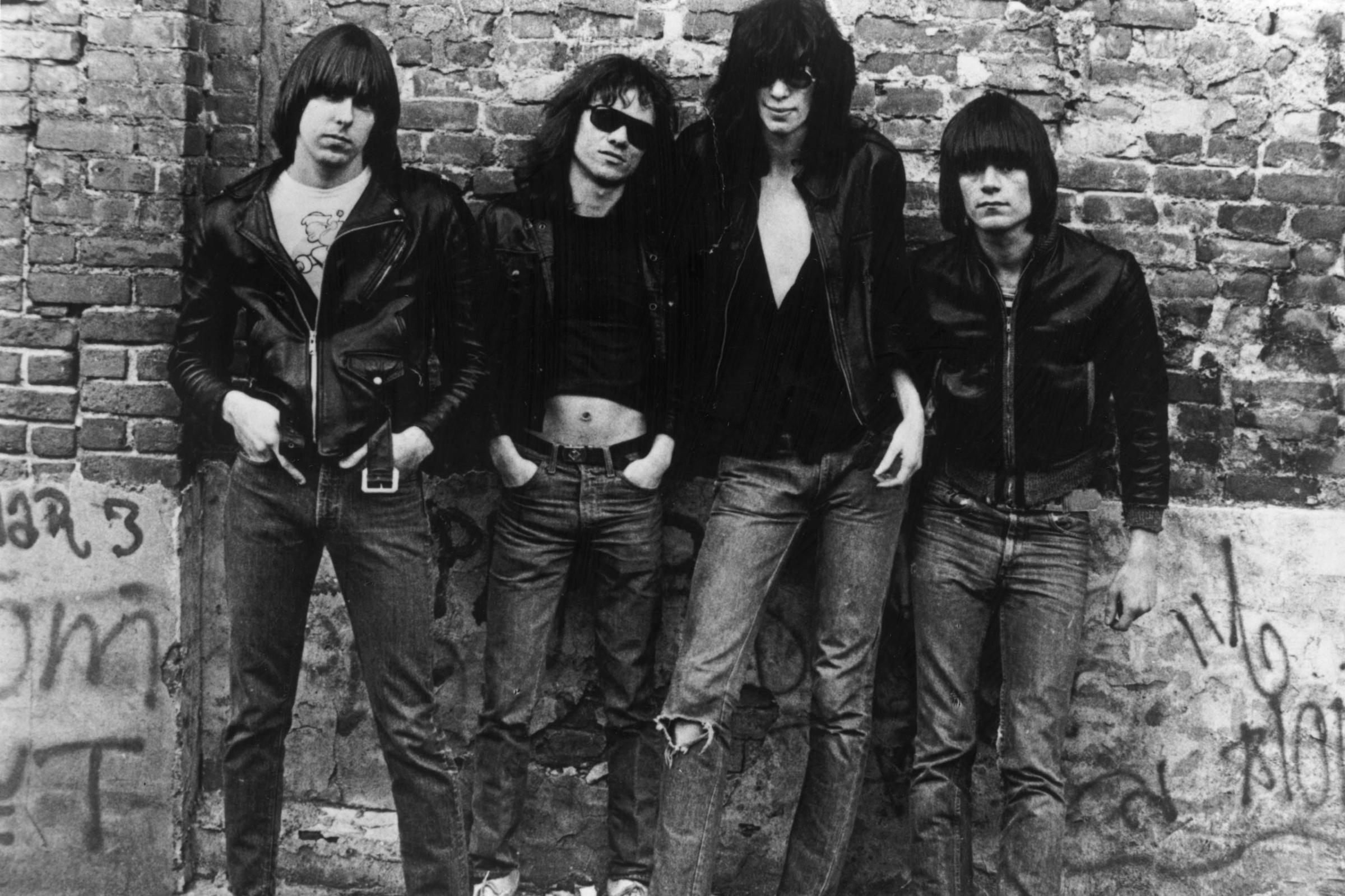

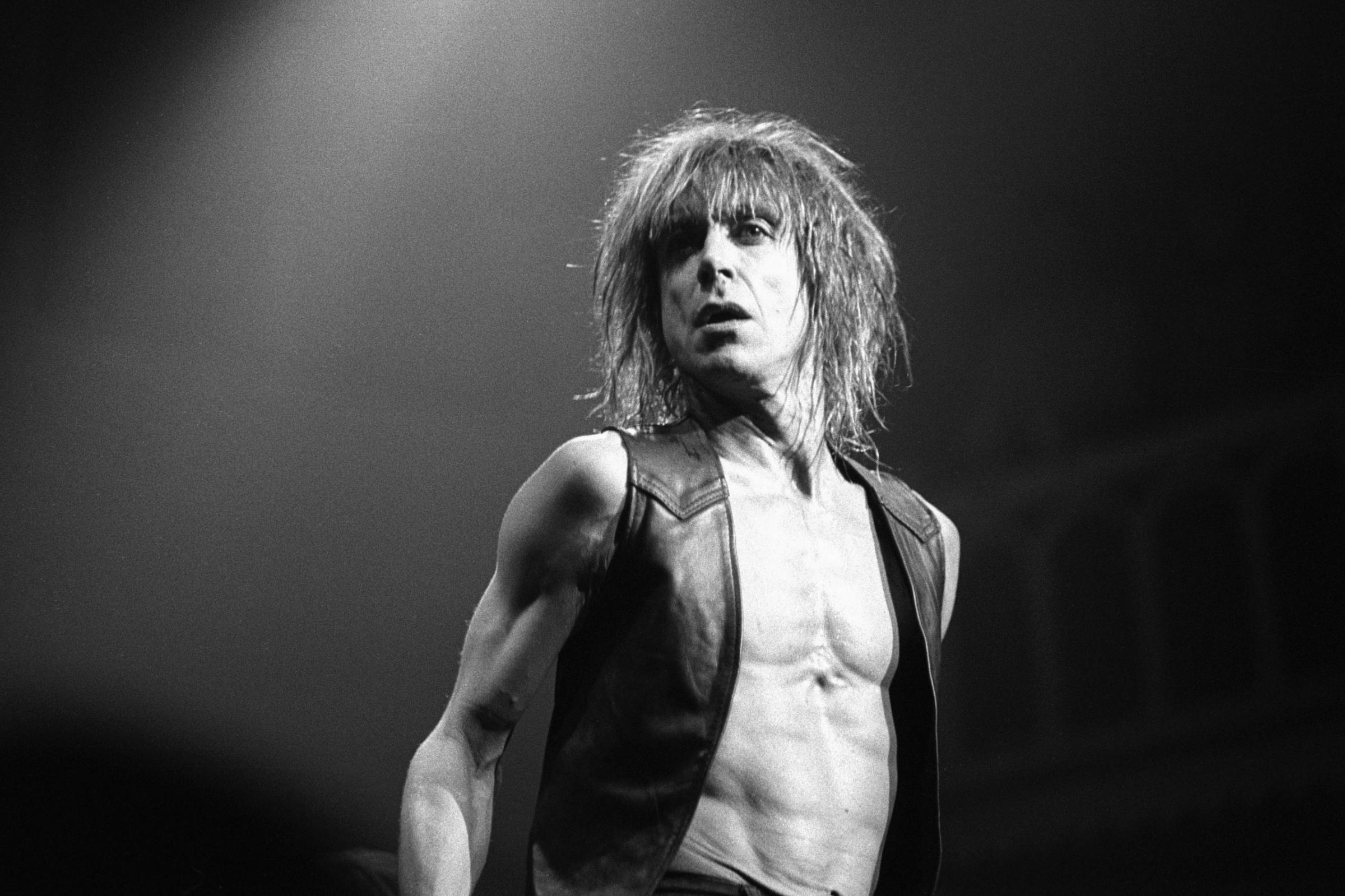

Artists Who Have Never Won A Grammy

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com