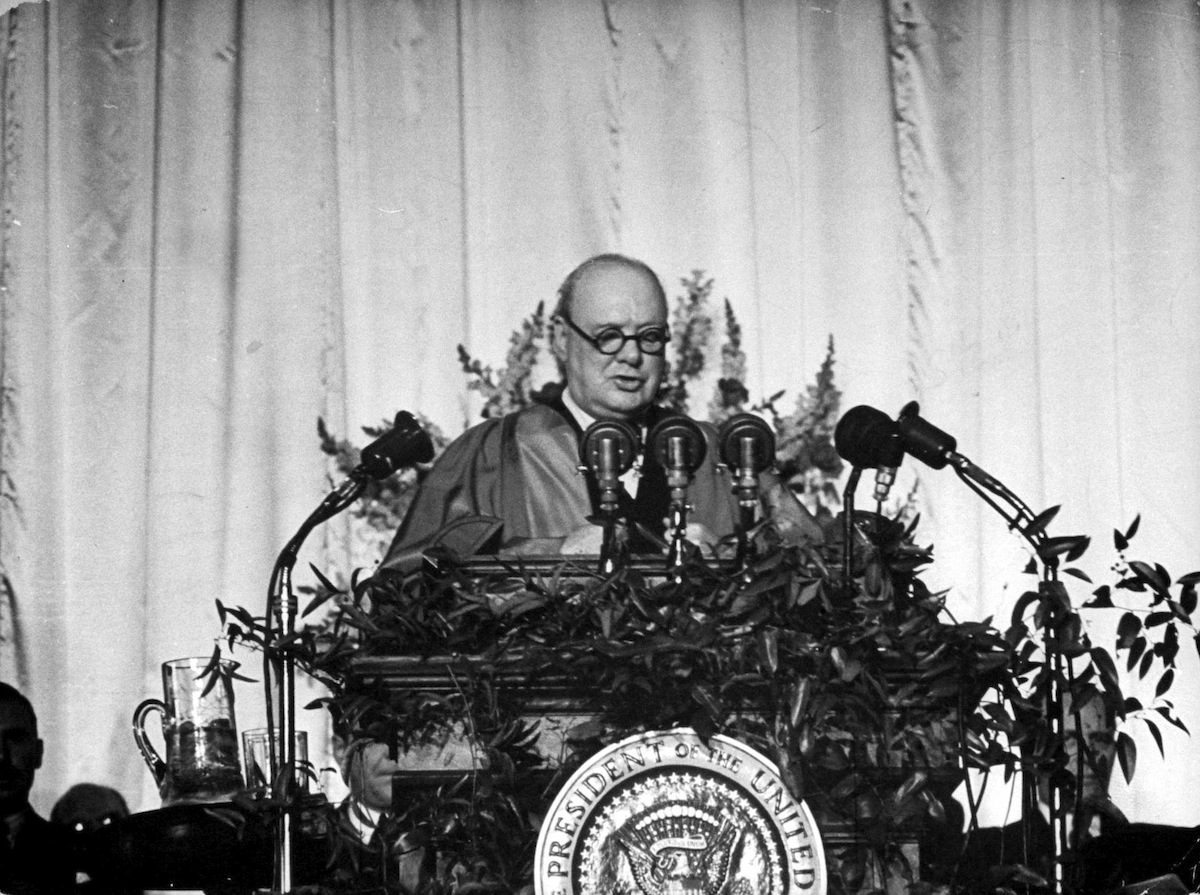

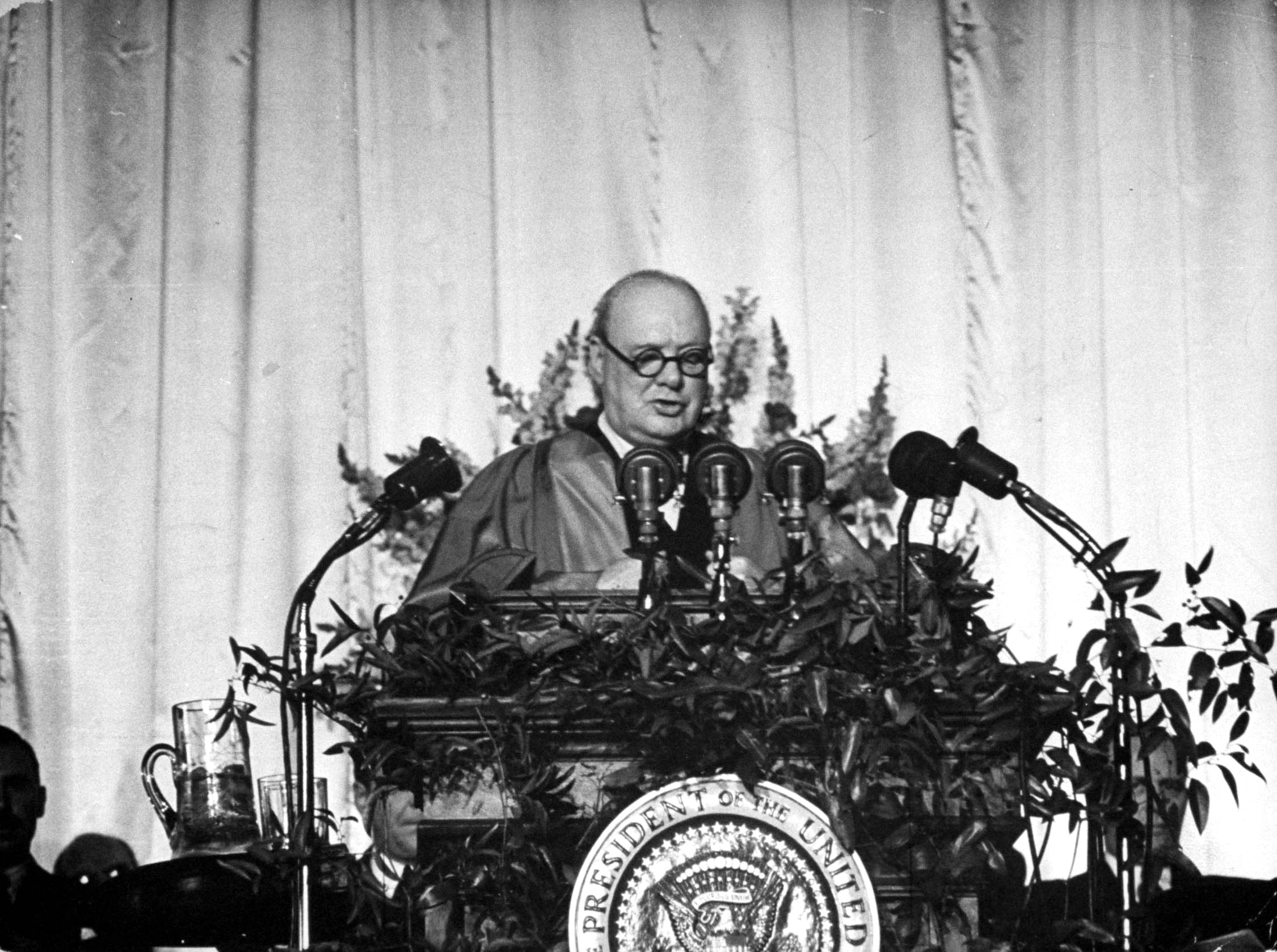

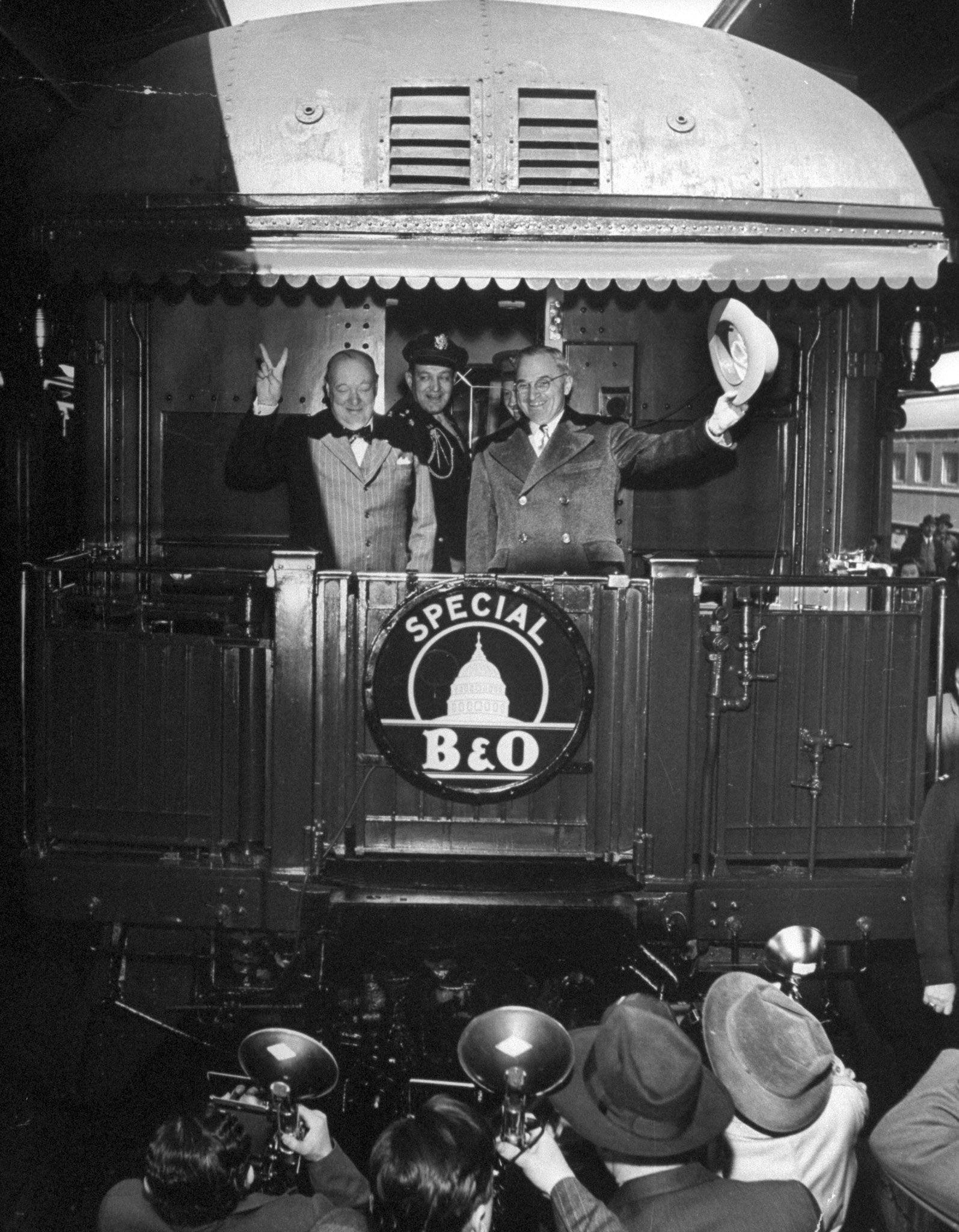

Exactly 69 years ago, on Mar. 5, 1946, Winston Churchill stood in a college gymnasium in Fulton, Mo., at the beginning of the Cold War, while President Harry S. Truman sat behind him in a gown and mortarboard. Speaking to students gathered at Westminster College, he accepted an honorary degree and famously condemned the Soviet Union’s ways: “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.”

The actual title of Churchill’s speech was “Sinews of Peace,” though most people know it as the “Iron Curtain speech.” Over the years there has been another twist of the record. Churchill often gets credit for coining that metallic metaphor—on that stage—for the figurative barrier drawn across Europe between the capitalist West and the communist East. But he did not. In fact, there’s evidence of the phrase being used to mean exactly that a good 26 years earlier when an E. Snowden (seriously) published a travelogue about her adventures in Bolshevik Russia.

So why do quotes get false histories? Lots of reasons.

Misattribution can be convenient. It’s easy not to question a coinage that it seems plausible—especially when it just so happens to give us good gravitas by association.

“You reach for a famous name to give authority,” says Elizabeth Knowles, editor of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. “You want to say Churchill said it. Because you have associated what you’re saying with that particular person, it gives the saying a bit more oomph.” Iron curtain just feels like something a dulcet, witty orator like Churchill would come up with, right? And it’s a much clearer signal that you’re educated and that your words have heft if you attribute a quote to Winston Churchill than to Snowden, an unremembered member of a trade-union delegation.

Many times people invoke quotations that were never said at all.

“Play it again, Sam.” Neither Bogart nor Bergman said these words.

“Elementary, my dear Watson.” Doyle wrote no such thing.

“Beam me up, Scotty.” Sorry, nope.

These get passed on because we wish people had uttered them. “A misquotation of that kind can be, almost, what you feel somebody ought to have said,” says Knowles. “It summarizes for somebody something very important about a particular film, a particular relationship, a particular event.” Even if it’s made up and especially if it’s close to things people really did say, we embrace it as gospel. After all, Bergman did utter, “Play it, Sam,” in Casablanca. And Bogart did say, “If she can stand it, I can! Play it!”

Sometimes misquotations get handed down because they convey the right idea and sound better to us than what the person actually said.

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln gave a speech in which he said, “To give victory to the right, not bloody bullets, but peaceful ballots only, are necessary.” Over time, that sentiment been recrafted as, “The ballot is stronger than the bullet.” The latter version is snazzier. Even when sources know this precise phrasing was probably never really used by Lincoln, they continue to pass it on. Take Dictionary.com’s quotes site, where the well-sourced quote from 1858 is in the fine print. Also in fine print is the admission that the quote in giant font across the top of the page was “reconstructed” 40 years after Lincoln was supposed to have said it. Which, as far as editors at Oxford are concerned, he did not.

“It’s a very natural thing, that we edit as we remember,” Knowles says. “So when we quote something we very often have in mind the gist of what’s being said. So we may alter it slightly and we may just make it slightly pithier or simpler for someone else to remember. And that’s the form that gets passed on.”

While it may be easier to remember that Churchill invented the iron curtain, here’s the real history:

In its earliest use, circa 1794, an “iron curtain” was a literal iron screen that would lowered in a theater to protect the audience and auditorium from any fire occurring backstage. From there, it became a general metaphor for an impenetrable barrier. In 1819, the Earl of Muster described the Indian river Betwah as an iron curtain that protected his group of travelers from an “avenging angel” of death that had been on their heels in that foreign land. Then, in 1920, Ethel Snowden made it specifically about the East and West in Throughout Bolshevik Russia (1920):

At last we were to enter the country where the Red Flag had become a national emblem, and was flying over every public building in the cities of Russia. The thought thrilled like new wine … We were behind the ‘iron curtain’ at last!

Read TIME’s original coverage of the Mar. 5, 1946, speech, here in the TIME Vault: This Sad & Breathless Moment

Read next: You Can Now Own a Vial of Winston Churchill’s Blood

See Photos From the Speech that Made 'Iron Curtain' a Household Term

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com