Nearly a century after it made its grisly debut, the mysteries surrounding Spanish flu continue to plague epidemiologists. In 2005, as Slate has reported, scientists succeeded in sequencing the virus’ RNA — eight years after exhuming a flu victim’s frozen corpse from an Alaskan grave to obtain a sample. But they still don’t know exactly where the virus came from or how it achieved such staggering lethality, killing more than half a million Americans and an estimated 50 million people worldwide in a single year.

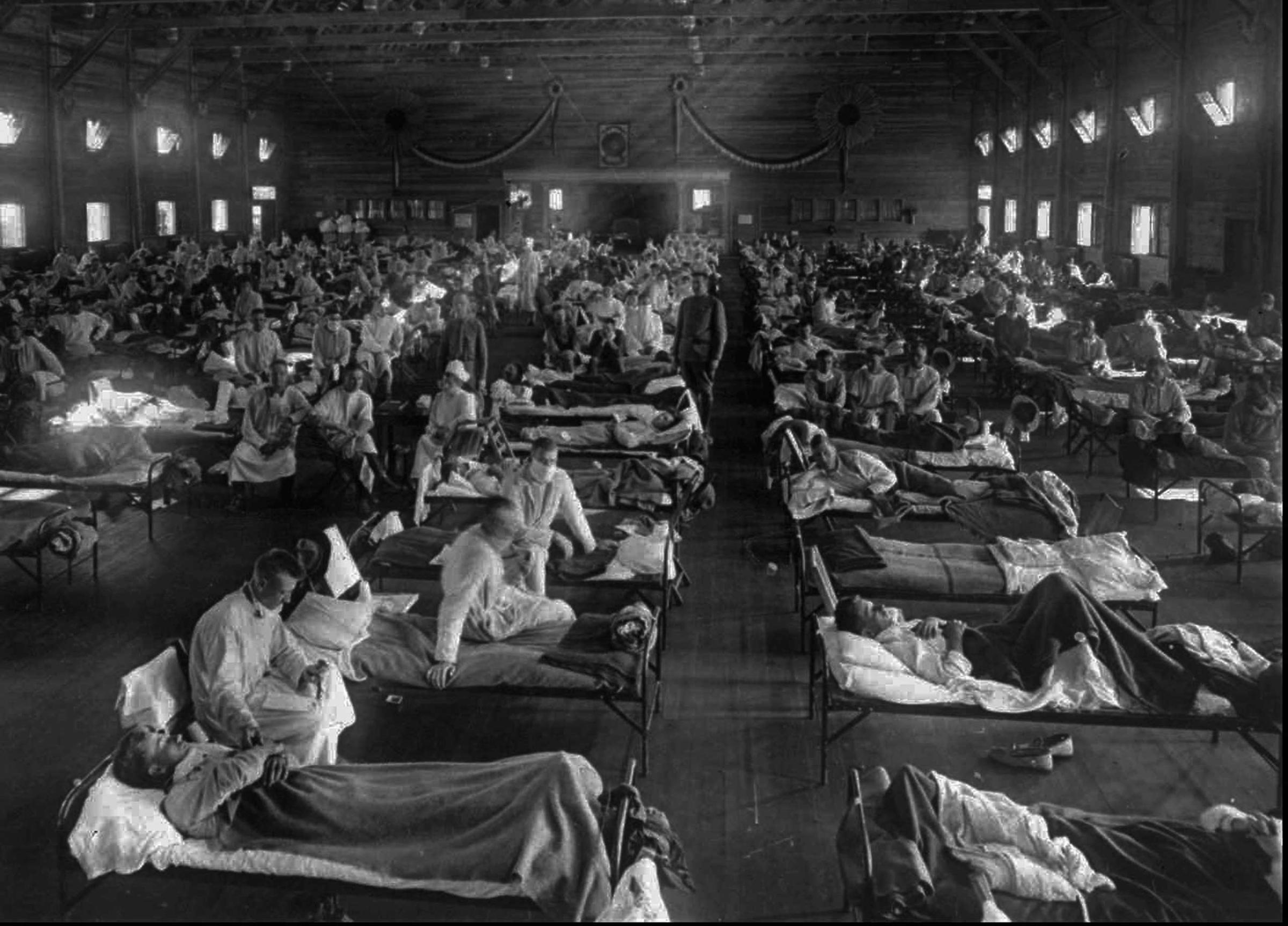

Some researchers believe the story began on the morning of this day, Mar. 11, 1918, when a soldier in Fort Riley, Kans., went to the camp infirmary with a fever. According to the PBS documentary Influenza 1918, more than 100 soldiers had reported to the infirmary by noon. Within a week, that number had quintupled. Several dozen soldiers died there that spring, before the contagion seemed the ebb; the official cause was pneumonia.

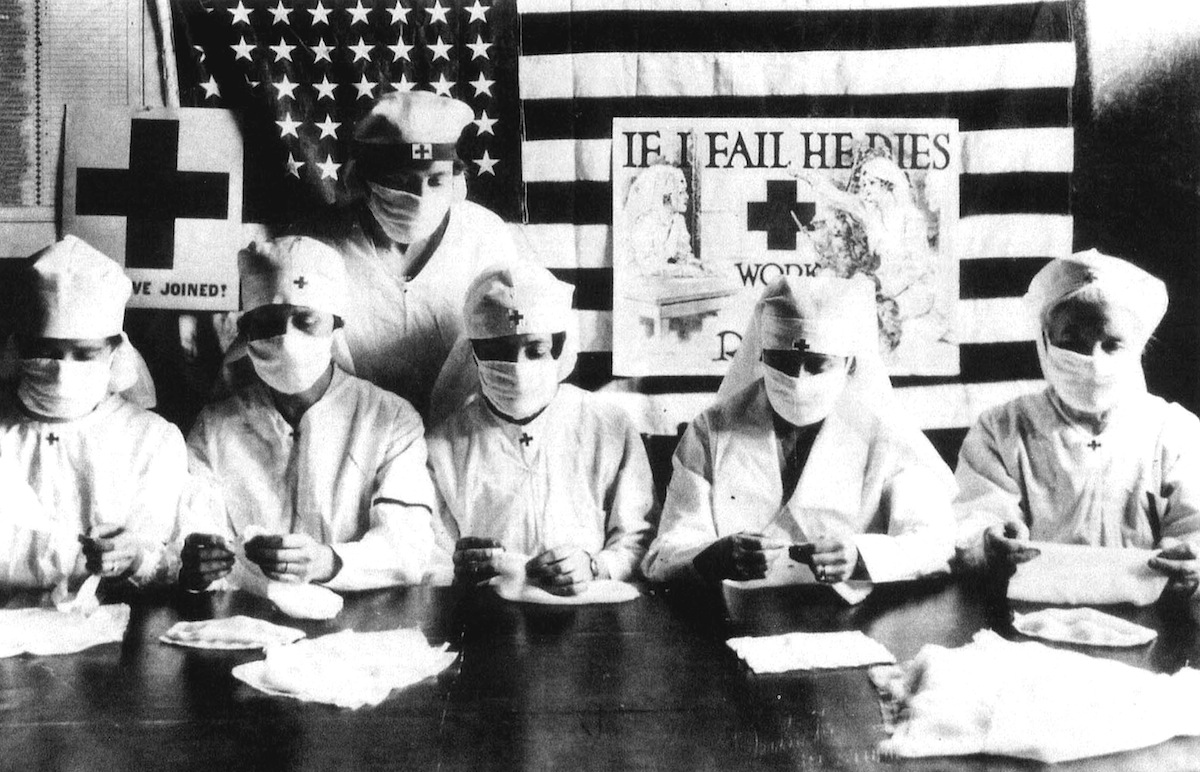

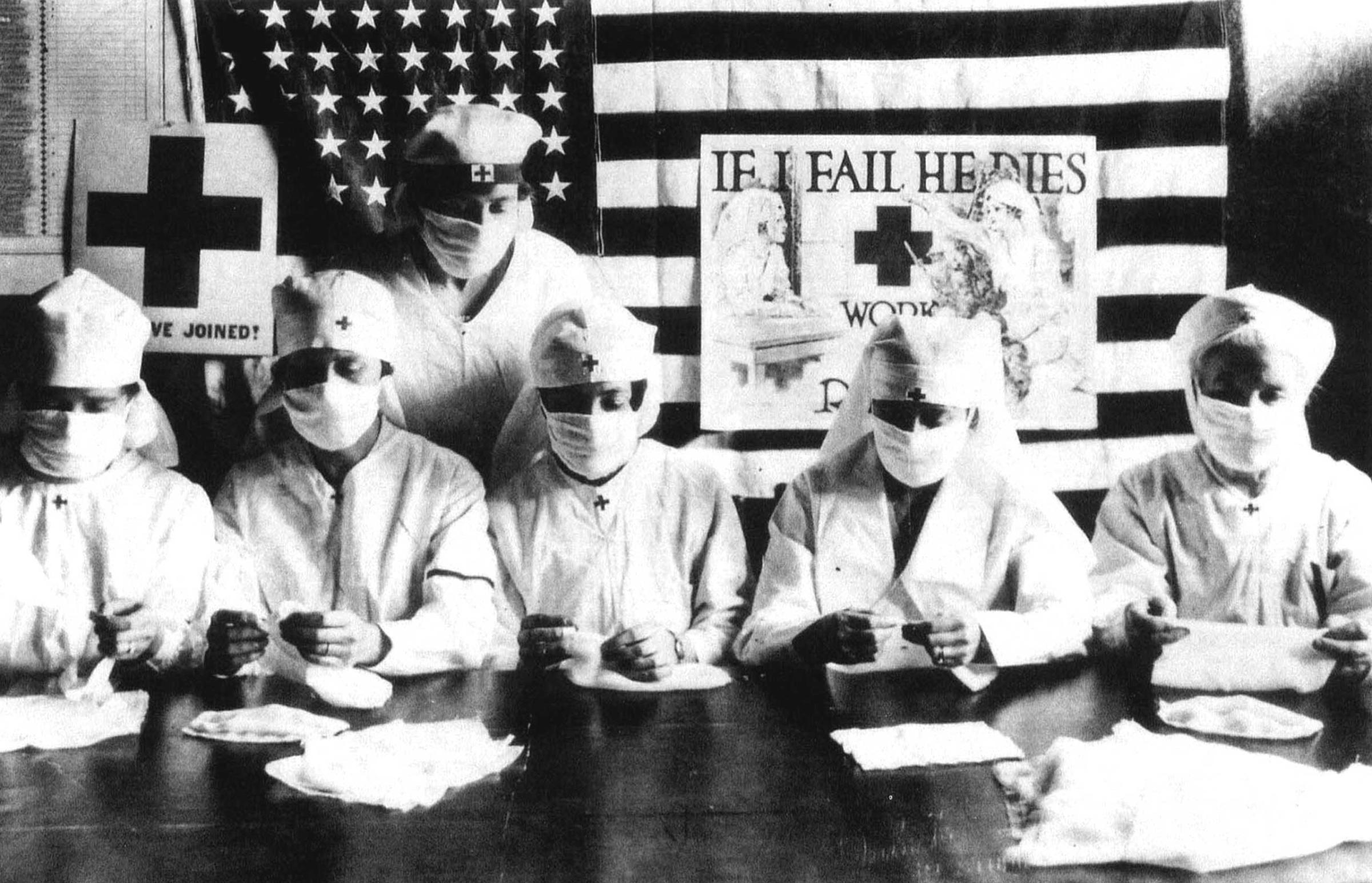

The 1918 Flu Pandemic: Scenes From a Cataclysm

As soldiers fanned out to fight World War I, however, the virus made its way around the globe, from European battlefields to remote areas of Russia and Greenland, spawning two more pandemic waves that were even deadlier than the first. (It became known as Spanish flu only because the Spanish news media was the first to widely report the epidemic, which had been hushed by wartime censors elsewhere in Europe.)

What made this flu different from all other flus was a dramatically higher fatality rate, plus the fact that while ordinary flus claimed casualties among the very young and the very old, this virus was especially deadly to young adults between the ages of 20 and 40. And their deaths weren’t pretty. As Slate tells it, “Many sufferers came down with severe nosebleeds — some spewed blood out of their nostrils with such force that nurses had to duck to avoid the flow. Those unable to recover eventually drowned in their own bodily fluids.”

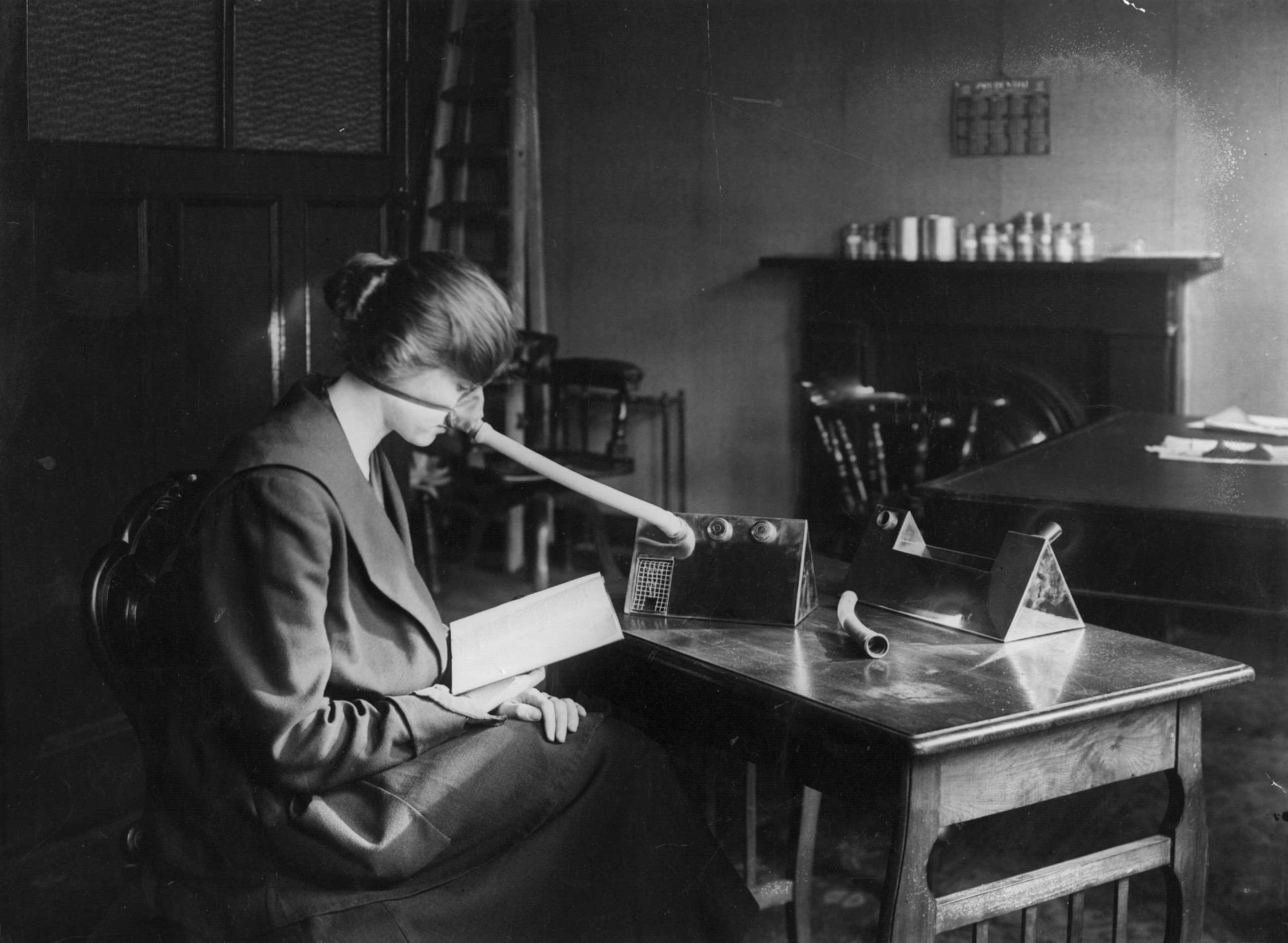

Why Spanish flu was so fatal, especially to people in the prime of their lives, is what scientists are striving to understand, as TIME reported in the wake of Hong Kong’s 1997 avian flu outbreak. It was during that outbreak that a pathologist named Johan Hultin collected an intact, long-frozen sample of the Spanish flu virus from a mass grave in a tiny Alaska town called Brevig Mission, where 85 percent of the population had been felled by the flu in a single week. Research on that sample has shown that one way Spanish flu worked was by overstimulating the immune system and turning it against its owner — so having a strong immune system to begin with may have been a disadvantage.

But there is more to it than that, other scientists say. And understanding the full story of Spanish flu could help develop vaccines to protect us from the next flu epidemic — an epidemic that is inevitable, as Hultin told TIME in 1998. In the meantime, there’s only one surefire method of surviving pandemic flu, according to Hultin: Isolate yourself in a mountain hideaway until the outbreak subsides. TIME explains: “It was a tactic… successfully used in 1918 by a village just 30 miles from Brevig. Its elders, after learning of the advancing plague, stationed armed guards at the village perimeter with orders to shoot anyone who tried to enter. The village survived unscathed.”

Read original coverage of the Hong Kong outbreak, here in the TIME archives: The Flu Hunters

Read next: Why the Government Has Legal Authority to Quarantine

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com