Correction appended, Mar. 5, 2015

When the U.S.S. Cyclops went off the grid somewhere north of Barbados, it became one of the most popular examples of the uncanny dangers lurking within the Bermuda Triangle.

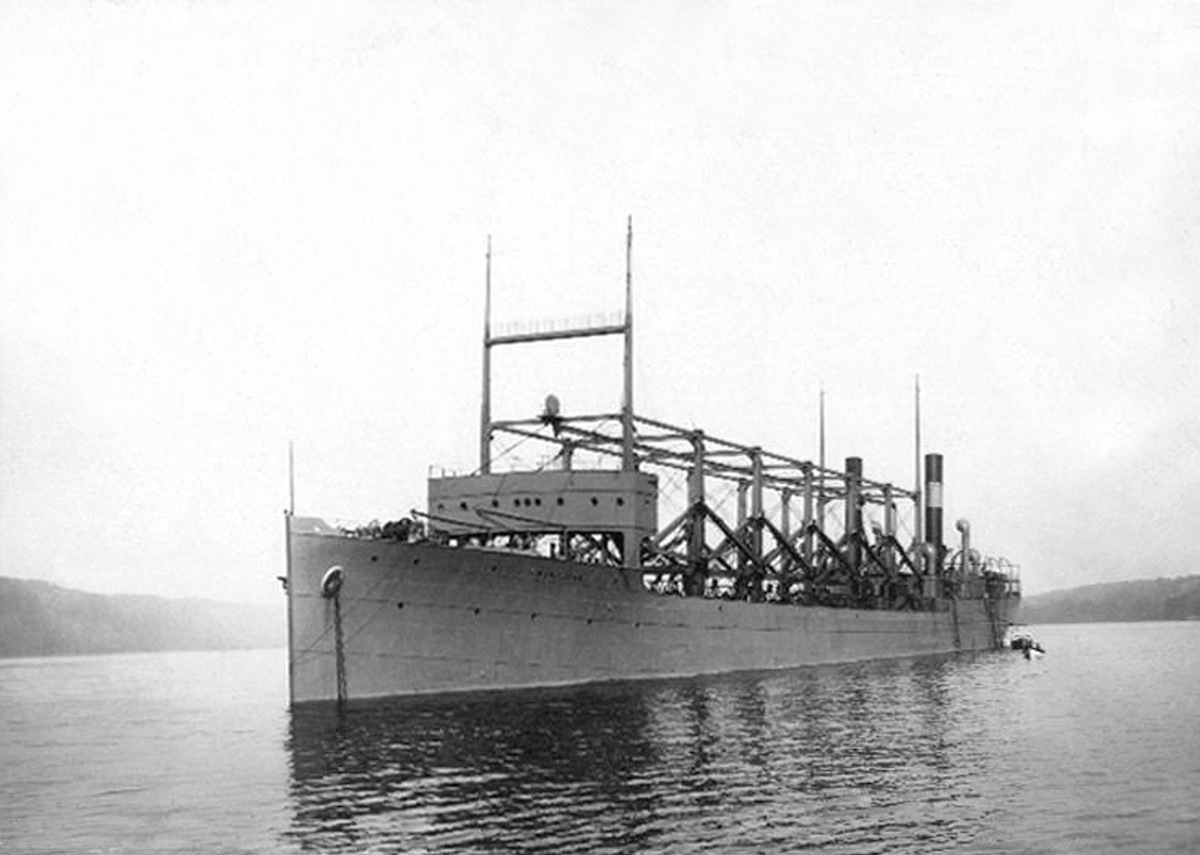

One of the Navy’s largest fuel ships, the Cyclops was last seen on this day, Mar. 4, in 1918, when it stopped in the West Indies on its way from Brazil to Baltimore, carrying 10,800 tons of manganese ore to be used in manufacturing munitions. But the ship never made it to Baltimore, nor did any of its 300 or so passengers and crewmembers. Despite an exhaustive search effort, no trace was ever found of the ship, and Naval investigators never landed on a definite cause for its disappearance.

What made it all the more mysterious, according to a contemporary New York Times account, was that the captain never sent a distress signal, nor did anyone aboard respond to radio calls by the hundreds of American ships in the vicinity. What’s more, there were no storms strong enough to cause the Cyclops to founder, according to the Times, which went on to suggest that the ship might have been the target of German mines or U-boats. According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, one contemporary magazine suggested that a giant octopus had “[risen] from the sea, entwined the ship with its tentacles, and dragged it to the bottom.”

The Navy, however, discounted the likelihood of either German or giant octopus attacks, opening the door to more supernatural speculation, and the Cyclops joined the list of more than 100 ships and planes to have disappeared under strange circumstances in the triangular region roughly bounded by Bermuda, Miami and Puerto Rico.

While the Bermuda Triangle became a cultural fixation of the 1950s and 1960s, it has by now been repeatedly and comprehensively debunked. Its reputation as a kind of earthly black hole suffers every time a vanished plane or vessel reemerges.

And although there’s still no trace of the Cyclops, there is, at least, an alternate explanation. It centers on a captain more eccentric than Ahab, with a fondness for “pacing the quarterdeck wearing a hat, a cane and his underwear,” and against whom some of his crew had already attempted a mutiny before they reached Barbados, per the Navy. As quoted in Gian Quasar’s book Distant Horizons, the U.S. Consul in Barbados wrote to the State Department following the ship’s disappearance, noting that the captain had appeared to be deeply disliked by his fellow officers, and that in suppressing the recent mutiny attempt, he had imprisoned members of his crew and executed one.

“While not having any definite grounds I fear fate worse than sinking,” the consul writes, “though possibly based on instinctive dislike felt towards master.”

Read about the 1991 discovery of five lost bombers, here in the TIME archives: Lost Squadron

Correction: The original version of this post included a reference to the Lost Squadron of Navy bombers being found in 1991. It was later discovered that the wreckage had been misidentified.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com