“It’s like what happened after we dropped the [atom] bomb in World War II. The results were so catastrophic that now we’ll do anything to avoid dropping another one.”

That’s how John Lombardi, former president of the University of Florida, described the so-called “death penalty” levied upon Southern Methodist University in 1987 after the NCAA determined that the school had been paying several of its football players.

Until the punishment came down—on this day, Feb. 25, in 1987—SMU had seemed like the opposite of a cautionary tale. The tiny Dallas university, with just 6,000 students, had finished its 1982 season undefeated, ranking No. 2 in the nation and winning the Cotton Bowl, and added a second Southwest Conference championship to its résumé two years later. The SMU of the early 1980s stood toe-to-toe with conference powers Texas, Texas A&M and Arkansas—and proved itself their equal.

Trouble was, SMU needed help standing with those giants. There aren’t many ways to build a dominant football program on the fly, but if you’re going to try, you need a coach who can convince a bunch of teenagers that they’re better off coming to your unheralded program than they are heading down the road to Austin or College Station or hopping a plane to Los Angeles or South Bend. That’s no easy task, even for a recruiter as gifted as Ron Meyer, who became SMU’s head coach in 1976. Sometimes promises of playing time or TV exposure aren’t enough—especially when your competitors are offering the same things, only more and better. Though the Mustangs weren’t caught till a decade after Meyer arrived in Dallas, there’s every reason to suspect SMU and its boosters had been bending the rules for years.

When the other cleat dropped, it dropped hard. The death penalty—part of the “repeat violators” rule in official NCAA parlance—wiped out SMU’s entire 1987 season and forced the Mustangs to cancel their 1988 campaign as well. So, when Lombardi compared the punishment to the nuclear option, in 2002, the analogy seemed like an apt one. For years, scorched earth was all that remained of the SMU football program, and of the idea of paying players.

Now, however, the conversation has changed.

Dallas itself played a major role in the rapid rise and ferocious fall of the Mustangs. By the 1970s, the northern Texas city was a growing metropolis, a hub for businessmen who had recently acquired their fortunes thanks to oil and real estate. Virtually to a man, each had a college football team he supported, and with that support came an intense sense of pride, not to mention competition. Combine that environment with the enormous success of the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys during the 1970s as they assumed the title of “America’s team,” and it’s easy to see how so much pressure was placed on SMU.

With Ron Meyer’s arrival at the university, the goal became to dovetail the success of the Cowboys with the Mustangs’ performance—and he fit right in with the image that Dallas had begun to embody. He was brash, he was charming, he was dapper; the comparisons with Dallas’ J.R. Ewing came all too easily. And like Ewing, Meyer could be ruthless, pursuing recruits throughout eastern Texas with near-mythic fervor.

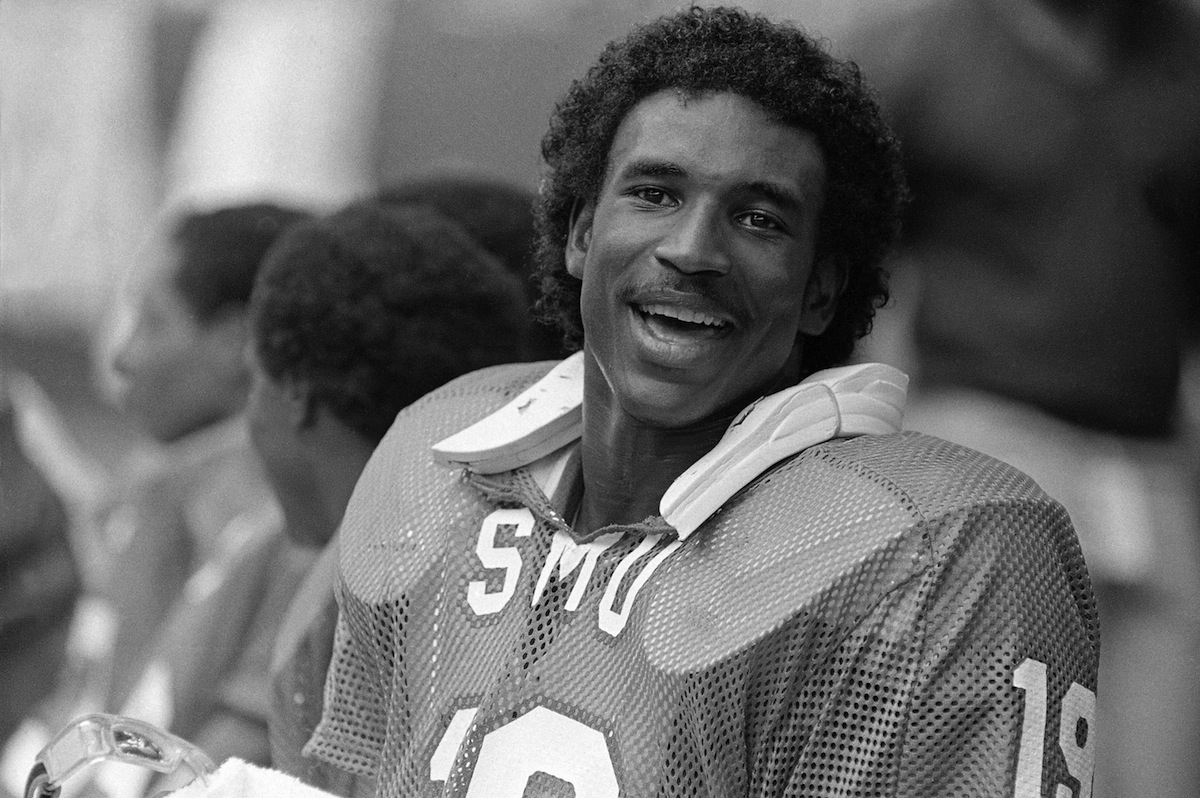

And the best myths have a dragon to slay. For Meyer, that dragon was Eric Dickerson. Dickerson was one of the nation’s top prospects—a high school running back so gifted he could have chosen any school in the country to play for in 1979. By all accounts, SMU wasn’t even in the running. They’d come a long way toward respectability since Meyer had arrived, but still weren’t on a level with Oklahoma or USC or Notre Dame. Plus, Dickerson had already committed to Texas A&M (and famously received a Pontiac Trans-Am that SMU supporters had dubbed the ‘Trans A&M’ right around the same time). But then, suddenly, miraculously, Dickerson had a change of heart. He decommitted from A&M and picked SMU shortly thereafter.

To this day, that decision remains a mystery wrapped in an enigma. There’s a section of ESPN 30 for 30’s excellent documentary about the SMU scandal, The Pony Exce$$—a riff on the SMU backfield, Dickerson and classmate Craig James, which was dubbed ‘The Pony Express’—about Dickerson’s recruiting process. No one involved, from Meyer to the boosters to Dickerson himself, would say how he really ended up at SMU. But none of them were able to contain the smirks that crept across their faces when they talked about the coup. There’s a reason that a popular sports joke in the early ’80s was that Dickerson took a pay-cut when he graduated and went to the NFL.

Dickerson changed everything for the Mustangs. With him powering SMU’s vaunted offense, the team became a force to be reckoned with in the Southwest Conference. Greater success, however, brought with it greater scrutiny. SMU was in a difficult position because Dallas had such a vibrant and competitive sports media scene (led by the Dallas Morning News and the Dallas Times Herald) at the time—one increasingly focused on investigative journalism in the wake of Watergate. The school’s status as a relative neophyte in the world of big-time college football and lack of rapport with the NCAA also did them no favors. There’s little question that other programs in the Southwest Conference were engaged in recruiting practices that bent the rules when it was possible, but none had quite as many eyes on them as the Mustangs.

Bobby Collins took over in 1982 and led SMU to its undefeated season, after Meyer left to be head coach of the hapless New England Patriots, but the Mustangs would never again reach those dizzying heights. Despite a growing recruiting reach, Collins failed to lure top-caliber prospects to Dallas, even with the help of the program’s increasingly notorious group of boosters. Instead, SMU became better known for its damning misfires, the first of which was Sean Stopperich, a prep star from Pittsburgh. Stopperich was paid $5,000 to commit and moved his family to Texas, but SMU had failed to realize that Stopperich’s career as a useful football player was already over. The offensive lineman had blown out his knee in high school, spent little time on the field for the Mustangs and left the university after just one year. Upon his departure from SMU, Stopperich became the first key witness for the NCAA in its pursuit of SMU.

The first round of penalties came down in 1985, banning SMU from bowl games for two seasons and stripping the program of 45 scholarships over a two-year period. At the time, those were considered some of the harshest sanctions in NCAA history. In response, Bill Clements, chairman of the board of governors for SMU, hung a group of the school’s boosters—dubbed the “Naughty Nine” by the media—out to dry, blaming them for the program’s infractions and the university’s sullied reputations.

Shortly thereafter, the NCAA convened a special meeting to discuss new, harsher rules for cheating, the most severe of which was the death penalty. (Despite Texas’ reputation as a pro-death penalty state for felons, its universities were some of the new rules’ staunchest opponents.) Still, due to the sanction’s power, few believed it would ever be used.

If SMU had cut off its payments to players immediately, it might not have been. Instead, the school and its boosters implemented a “phase-out” plan, which meant they would continue paying the dozen or so athletes to whom they had promised money until their graduation. One of those students-athletes, David Stanley, came forward after being kicked off the team and gave a televised interview outlining the improper benefits he had received from SMU. His words alone may not have been enough to damn the university, but an appearance on Dallas’ ABC affiliate, WFAA, by Coach Collins, athletic director Bob Hitch and recruiting coordinator Henry Lee Parker sealed the program’s fate.

Their interview with WFAA’s sports director Dale Hansen is a mesmerizing watch. Hansen sets a beautiful trap for Parker involving a letter that the recruiting director had initialed, and the recruiting coordinator walks right into it, all but proving that payments to players came directly from the recruiting office. The fact that Parker, Collins and Hitch looked uncomfortably guilty the entire time didn’t help their case.

The NCAA continued gathering evidence, and on Feb. 25, 1987—a gray, drizzly day in Dallas—it announced it would be giving SMU the death penalty. The man who made the announcement, the NCAA Director of Enforcement David Berst, fainted moments after handing down the sentence, in full view of the assembled media. SMU football, for all intents and purposes, was dead. The team managed just one winning season from 1989 to 2008, in no small part because the rest of the university community had decided it wanted nothing to do with a program that had brought so much infamy to the school.

The initial reaction to the penalty—both in Dallas and throughout the country—was one of shock. The Mustangs had gone from undefeated to non-existent in just five years. Few, however, could deny that if the NCAA were going to have a death penalty, then SMU was certainly deserving of it. But the fallout from the penalty was worse than anticipated; perhaps not coincidentally, in the decades since 1987, the penalty has never once been used against a Division I school.

Over the last two decades, the conversation that surrounded SMU’s fall from grace has changed even more. These days, those in and around the world of college sports don’t talk much about what the penalties for paying players should be; instead, many are wondering whether there should be any penalty at all for paying college athletes. The arguments in favor of paying college athletes are manifold, especially considering they often generate millions on behalf of their universities. Few, however, would argue that players should be paid in secret (or while still in high school). Any sort of pecuniary compensation that student-athletes receive would, as in pro sports, require some sort of regulation.

Despite the recent groundswell of support, the NCAA appears reluctant to change its rules. At some point, the governing body of college sports may not have a choice, especially if wants to avoid further legal trouble.

Ron Meyer, the SMU coach who nabbed Eric Dickerson more than 25 years ago, would famously walk into high schools throughout Texas and pin his business card to the biggest bulletin board he could find. Stuck behind it would be a $100 bill. That sort of shenanigan may not be the future of college sports, but we may be getting closer to the day when money isn’t a four-letter word for student-athletes.

Read TIME’s 2013 cover story about the ongoing debate over paying college athletes, here in the TIME Vault: It’s Time to Pay College Athletes

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com