In the yard of the Coptic church in the village of al-Our, dozens listen to the words of a preacher speaking into a microphone. His words rise and fall as he says: “The life we live is but numbered days that will quickly pass, the Bible says.”

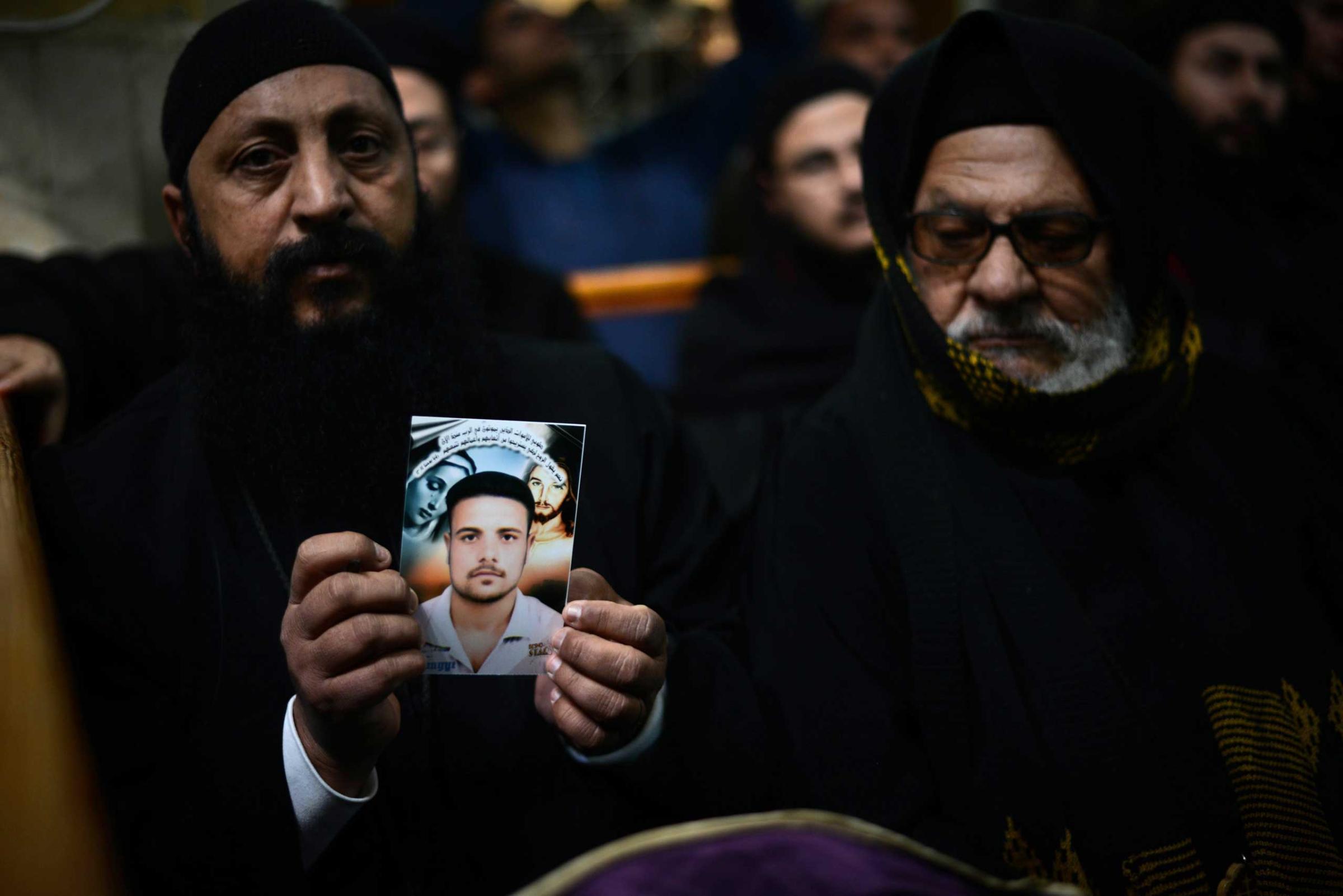

His words were intended to comfort a congregation mourning 13 of its members who were among the 21 men slaughtered on a Mediterranean beach in a video released last week by the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS). Al-Our is in Egypt’s Minya province, 150 miles south of Cairo, a farm community of some 6,000 Muslims and Christians living in brick, mud and stone houses. Following the spectacular murders of its residents, the town was thrust to the center of the crisis emanating from Libya, where ISIS has established a foothold in the chaos of a civil war.

“I felt peace knowing that they died as martyrs in the name of Christ,” says Bashir Estefanous Kamel, 32, whose two younger brothers and one cousin were among the victims. Kamel says he watched the video depicting the men’s execution as soon as it was available. “Of course, the first reaction was sadness at being separated from family.”

In Christianity, a person is considered a martyr if they are killed because of their faith. Christian martyrs include many early Christians such as St. Peter and St. Paul and more recent examples are priests and nuns killed in German concentration camps or during the Spanish Civil War. Egypt’s Coptic Christians, who make up between 10% and 20% of Egypt’s population of 80 million, are among many of the recent Christian martyrs. In two recent attacks by Muslim gunmen and mobs, eight Copts were shot in Nag Hammadi in 2010 and 21 killed in rioting in Kosheh in 2000. The ISIS victims are depicted next to the throne of Jesus on banners, which are suspended inside and outside the church in al-Our.

Like tens of thousands of other Egyptians, Kamel’s brothers, Bishoi Estefanous Kamel, 25, and Samuel Estefanous Kamel, 22, had gone to Libya in search of work they could not find at home. Even in recent years of turmoil, Libya’s oil-based economy continued to draw workers, especially from Egypt’s poorer regions. In al-Our, average residents earn between $3 and $4 a day. “It’s a hard life,” says Bashir Kamel. “If you don’t work all day, you don’t eat at night.”

Both brothers had completed two years of university, earning diplomas in industry and agriculture respectively, but could not find gainful employment in Minya. A few months after completing his mandatory military service, Samuel followed his older brother to Libya, where they worked as laborers in the city of Sirt, living among other Egyptian workers.

See Egyptian Coptic Christians Mourn Brothers Slain by ISIS

In December, the murder of an Egyptian Coptic doctor and his wife in Sirt punctured the workers’ sense of security. According to their older brother, Bishoi and Samuel Kamel had planned to return home to Egypt as soon as possible. Then, on Dec. 29, seven Copts were kidnapped from a minibus taking them back to Egypt. A second group was seized from their lodgings in Sirt days later. Bashir Kamel speculates that members of the first group of hostages disclosed the location of the workers’ housing under torture.

The night of the release of the execution video, the village priest, Father Makar Issa went from house to house in an attempt to comfort the families. “There was wailing in every street, every alleyway,” he says. “People were shocked.”

According to Issa, his congregants’ sorrow gave way, within days, to a kind of joy expressed at the men’s martyrdom. On the third day after the video, people gathered in the church. “The women were congratulating each other,” he says. As they left the church, women ululated.

“I am certain it had a positive effect, not a negative effect,” says Issa. “In the month and a half when the people were kidnapped, the whole congregation was coming to the church to pray for their return, but in their prayers later on, they asked that if they died, they die for their faith, and that’s what happened. The congregation is actually growing, psychologically and spiritually.”

Several relatives of the victims applaud Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi’s decision to bomb ISIS targets in eastern Libya within hours of the release of the execution video. “It’s an honor to us that our government did not let their blood be spilled cheaply,” says Bashir Kamel. “We feel proud.”

Egypt remains polarized in the wake of the military takeover, led by al-Sisi, in which elected Islamist President Mohamed Morsi was deposed in July 2013. But a powerful coalition stands behind al-Sisi, who has vowed to combat militancy.

Bebawi Yousef, 35, a teacher at a local private school whose two brothers were also killed, echoes Kamel’s sentiment. “We feel proud of our President Sisi. We feel he is keeping us safe.”

Sobhi Ghattas Hanna, whose cousin was killed, says he wants the world to stand with Egypt. “We feel comforted by Sisi’s stance. He ordered the military to strike Libya directly after the video was published,” he says. “We want the whole world to stand beside Sisi in his fight against terrorism.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com