It’s a peculiar thing to imagine leaving Planet Earth forever. But when a Dutch nonprofit called the Mars One project announced in 2013 that it was accepting applications for a one-way trip to another planet, I didn’t think twice about signing up.

It started off simply enough. Answer some questions about yourself, put together an audition video, and submit the application fee. More than 200,000 people answered the call, and I was excited to be one of them. That was really enough for me. I was sure my efforts would go nowhere, but at least I’d be able to say I’d thrown my hat in the ring. It’s not like I’m a trained astronaut, after all. I’m not even a scientist. I’m a political consultant with a husband, two extraordinary stepsons and a black-lab mix. But I wasn’t going to let a lack of training stop me from trying.

Space exploration has inspired me since I was a little girl. I would watch Star Trek with my parents and daydream about what other life forms might be out there waiting to meet us and what challenges we would face as a species if (and when) we found out we weren’t alone in the universe. As I got older, the daydreams became a tad more realistic. Could we ever reach out far enough into our galaxy to find that life? What technology would we need to develop to cover such tremendous distances? Are humans physically capable of spending that kind of time in space?

These are questions we’ll no doubt wrestle with for generations to come as we take the next small steps into outer space, but one thing is certain: space exploration and colonization are the next “giant leaps” for humanity. It’s human nature to explore, to question, to look out and wonder what lies beyond the horizon.

That spirit is at the heart of the Mars One project. They’ve picked up where Apollo left off, reigniting the dream of spaceflight in a way that low-earth-orbit shuttle missions, the International Space Station and unmanned cargo ships cannot. They talk of “going boldly” where we’ve yet to put human beings. But there’s just the tiniest catch. You don’t get to come home.

That’s where I usually lose people. “How can you leave forever?” “What does your family think about this?” “Your husband’s O.K. with you leaving him?” These are the questions I’m peppered with when I tell people this is a one-way trip. And these are reasonable questions, perfectly understandable, and they deserve well-considered answers. So here they are:

Space exploration is worth a human life. Every astronaut who has ever flown has known the risks they were up against once strapped into that ship. And there’s no guarantee that I won’t be crushed by a collapsing roof tomorrow or diagnosed with a terminal illness next year. Some call this a suicide mission. I have no death wish. But it would be wonderful if my death could be part of something greater than just one individual. If my life ends on Mars, there will have been a magnificent story and a world of accomplishment to precede it.

But that’s not what people really want to know. “How can you leave your family/your life/Earth for certain death?” they ask. Simple: In the beginning, it didn’t seem real. This was an easy conversation because there were so many applicants. When you’re one of more than 200,000, the odds are so long that you’ll be picked—never mind the technical hurdles—that the entire enterprise seemed like a lark, both theoretical and improbable, like writing in your own name for President. If there were consequences, they seemed abstract.

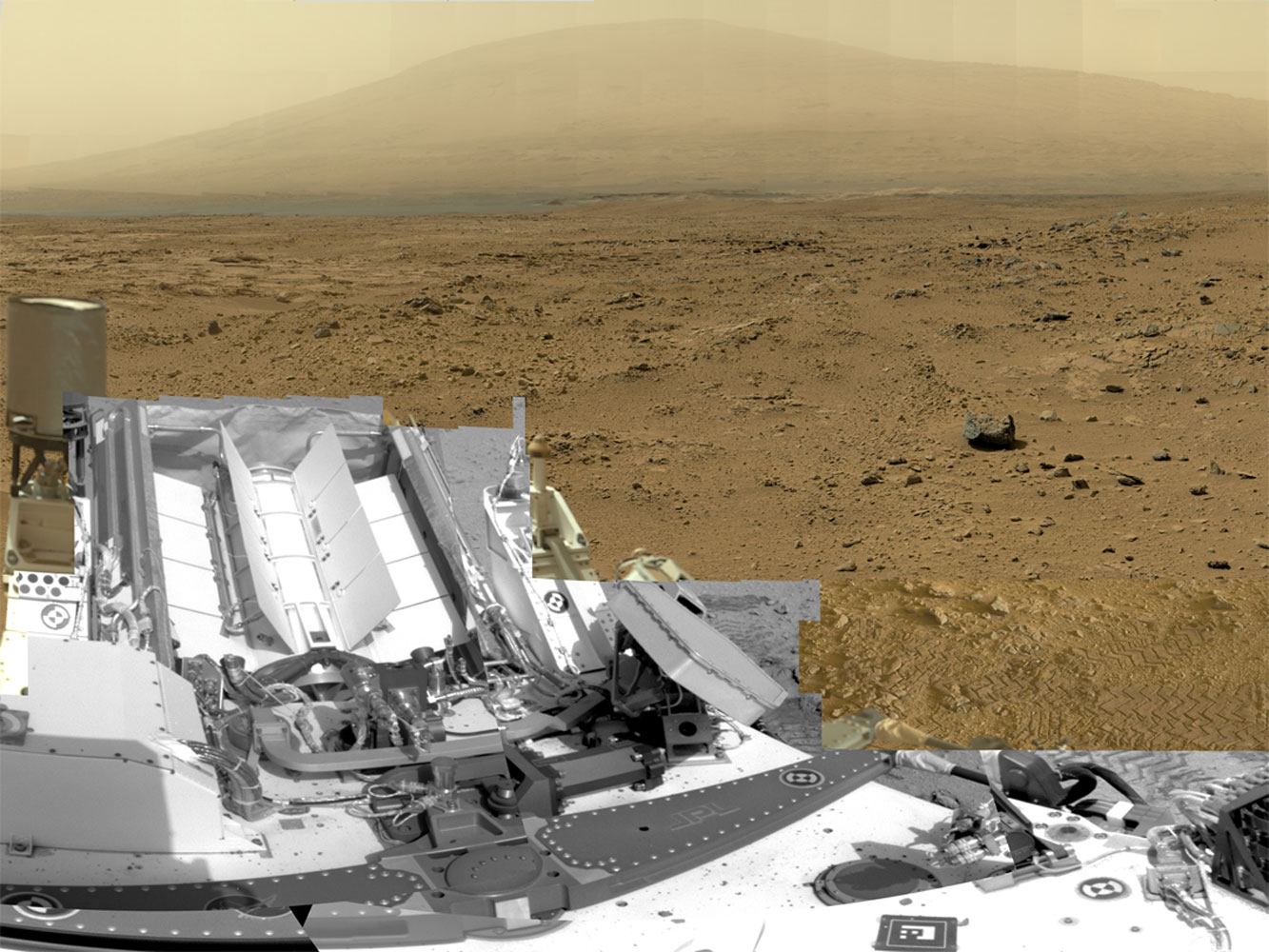

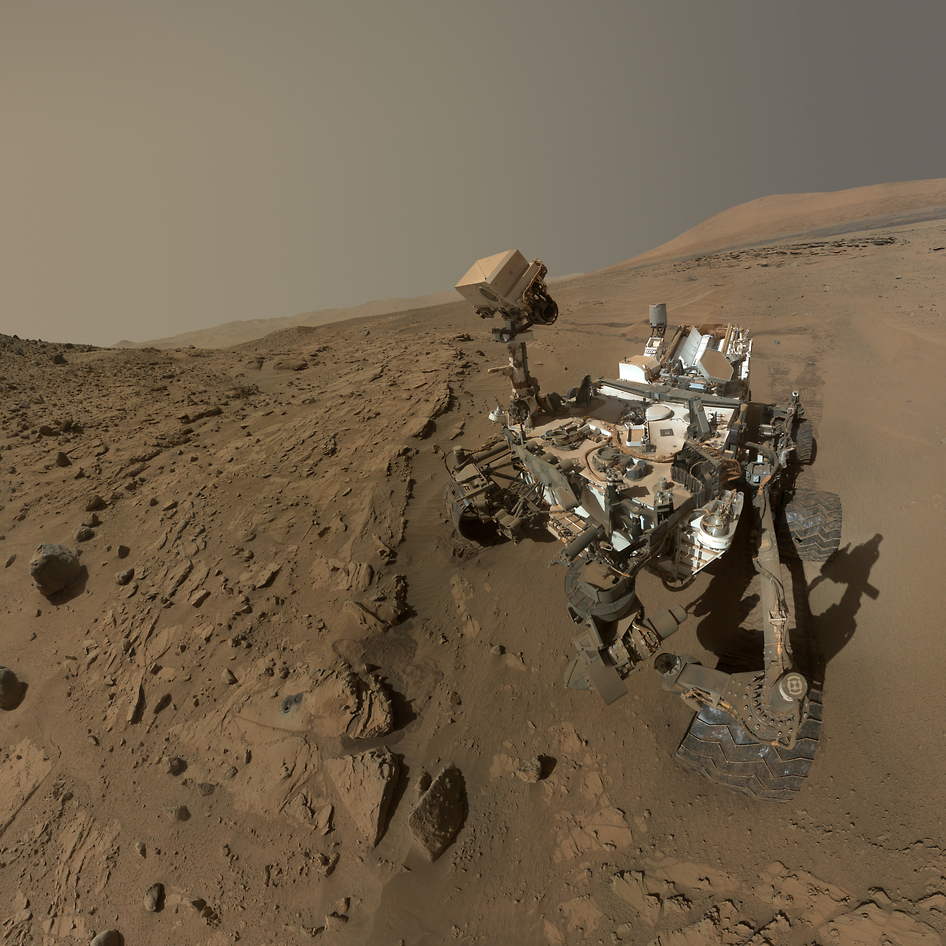

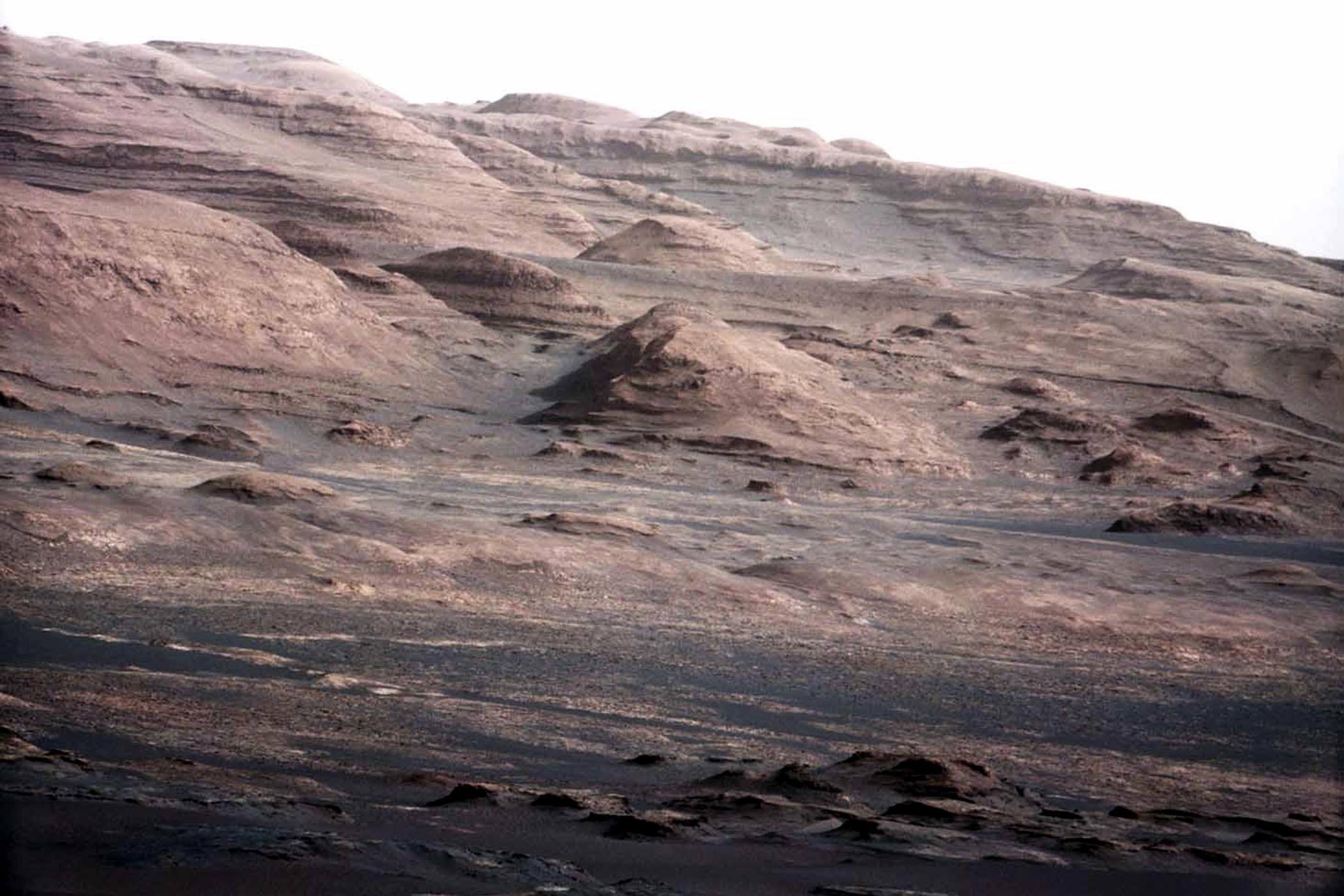

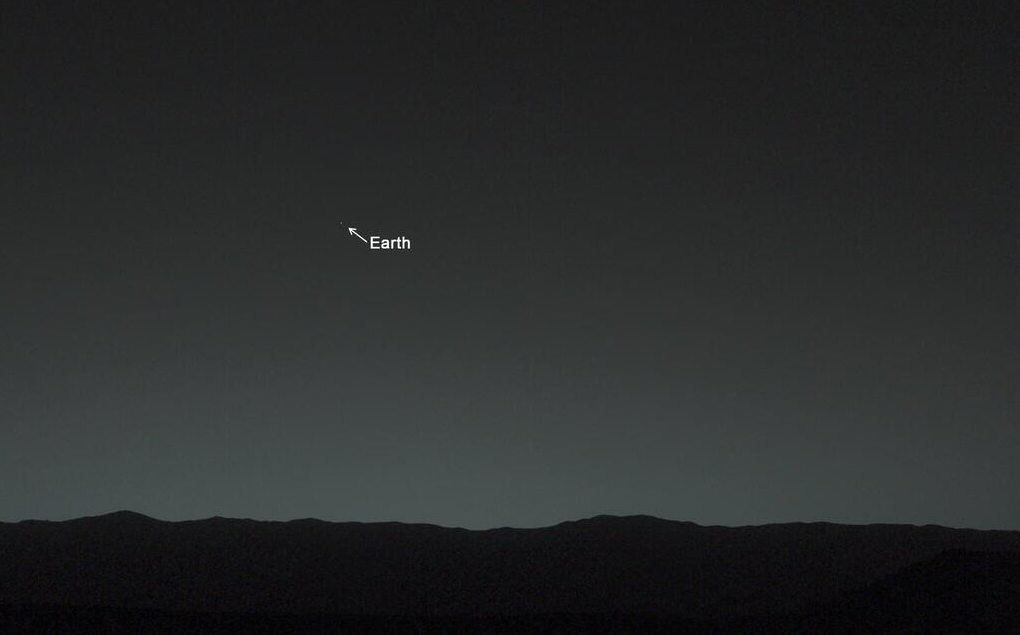

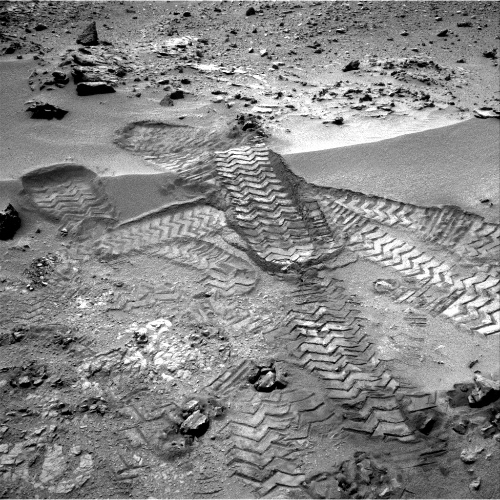

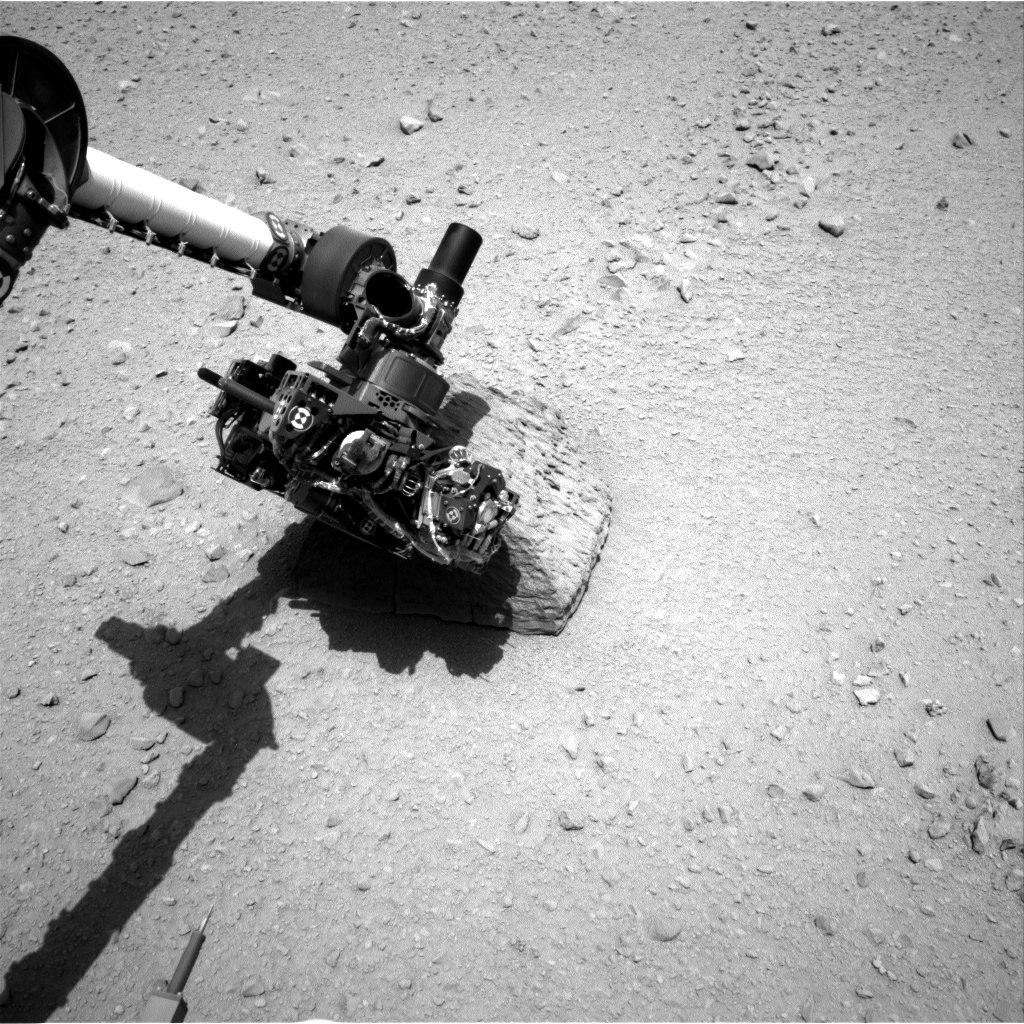

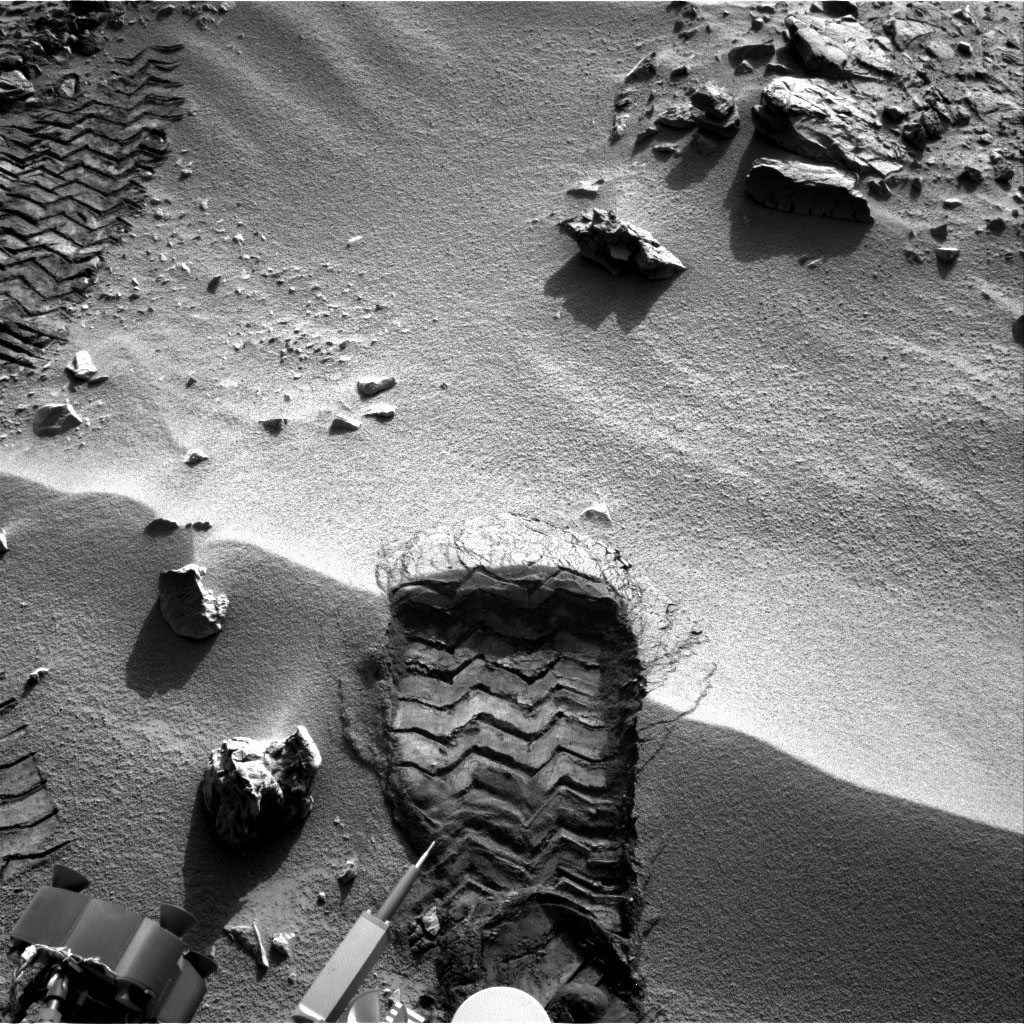

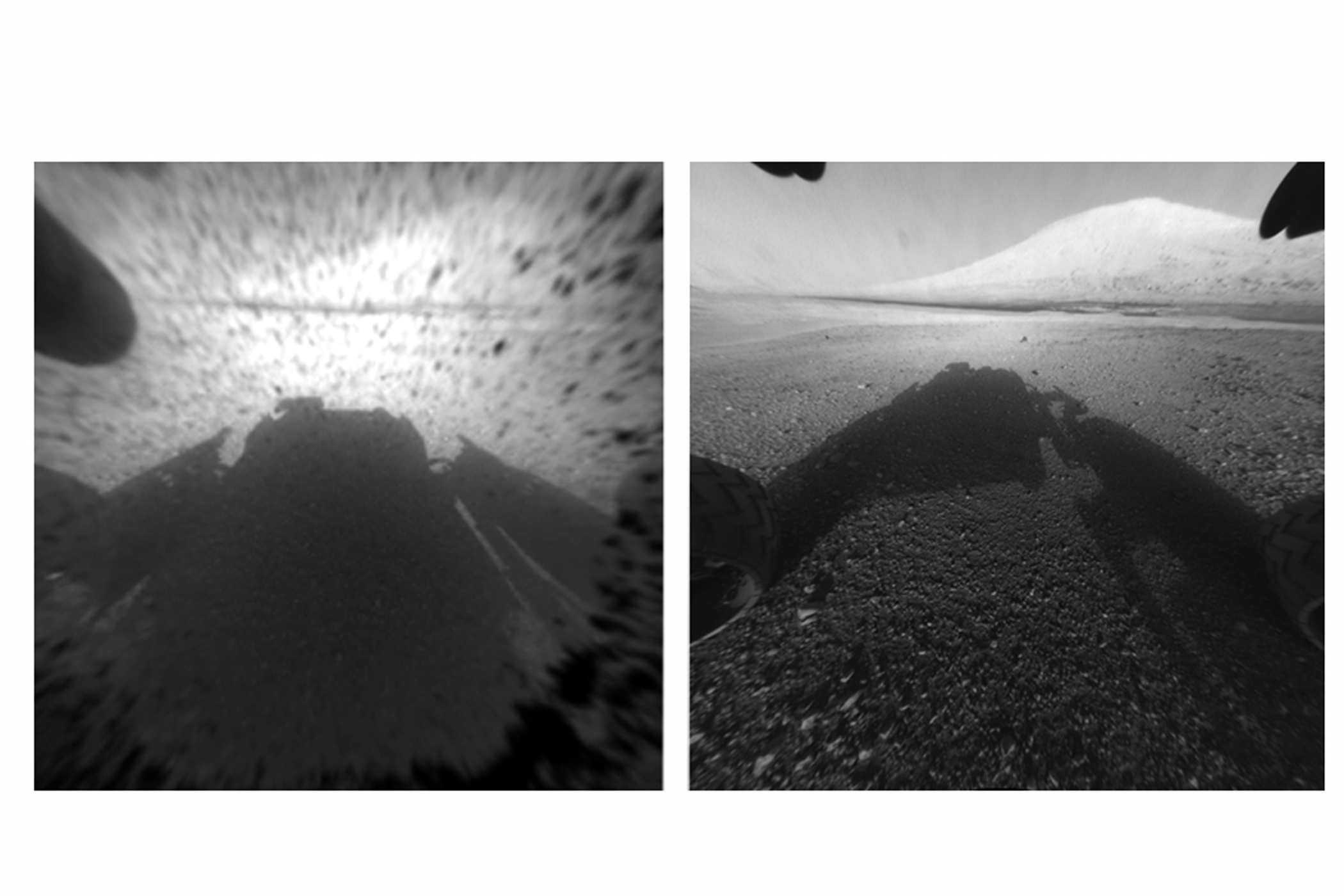

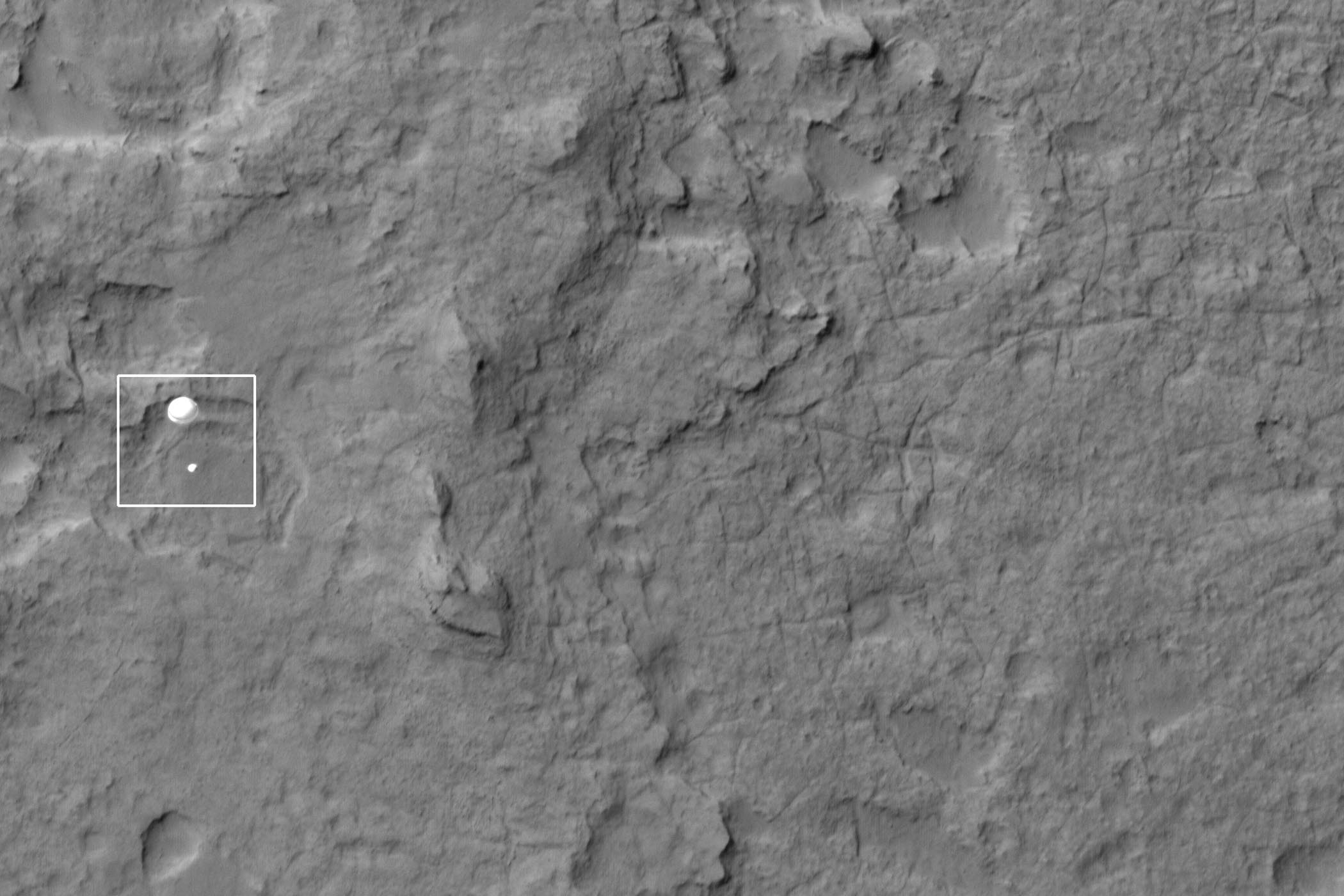

Photos from the Curiosity Rover’s First 2 Incredible Years on Mars

When I made the candidate list of just over 1,000, things became more interesting. People wanted to talk to me about it. I began to come up with answers and repeat them, which in itself became a way of not facing up to the potential reality of stepping off this planet forever. Staying on message became a way to stay away from my real feelings about this.

Now that I’m one of one hundred, the world is watching, looking to me for answers to questions that were easily brushed off when this was all just a fantastical daydream. The reality of this presses up against me, and I stay on message to protect that private space for me and my husband where I can face the hard questions that come at night. It’s one thing to imagine the good that can come from a manned mission to Mars, but it’s quite another to tally up the cost and see one’s life on the bill.

Paradoxically, I couldn’t even be contemplating this without the support of my family. My stepsons think it’s neat that their stepmom wants to fly off into space, even if it means I might not be around to see grandchildren. In doing this, I want to show them that there is no dream so great that it shouldn’t be chased. My father and sister think I’m a little nuts, but they know my reasons for doing this are about furthering a dream for mankind, not making a name for myself. And my husband, my incredible husband, has been my greatest advocate since the day I first applied. The promise I made to him on our wedding day was that our marriage would serve to make us the best versions of ourselves. He knows I’d walk away from Mars One without a second’s hesitation if he asked me to. And that’s why he won’t. He knows what this mission means to me.

The first launch of human beings won’t happen until 2024. That means we’re in Chapter 1 of a very long story. No one knows how this story will end. The mission might be scrapped over technical feasibility issues. The funding might not come together. They might have a hard time finding the right candidates. There are millions of things that have to happen for this to be a success, and there are plenty of things that can and will go wrong along the way. But Mars is humanity’s inevitable destination, and Mars One has accepted the challenge to take that next great leap. Now it’s up to us to live up to the adventure.

Read next: Astronauts Vying for One-Way Ticket to Mars May Be on Reality TV

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com