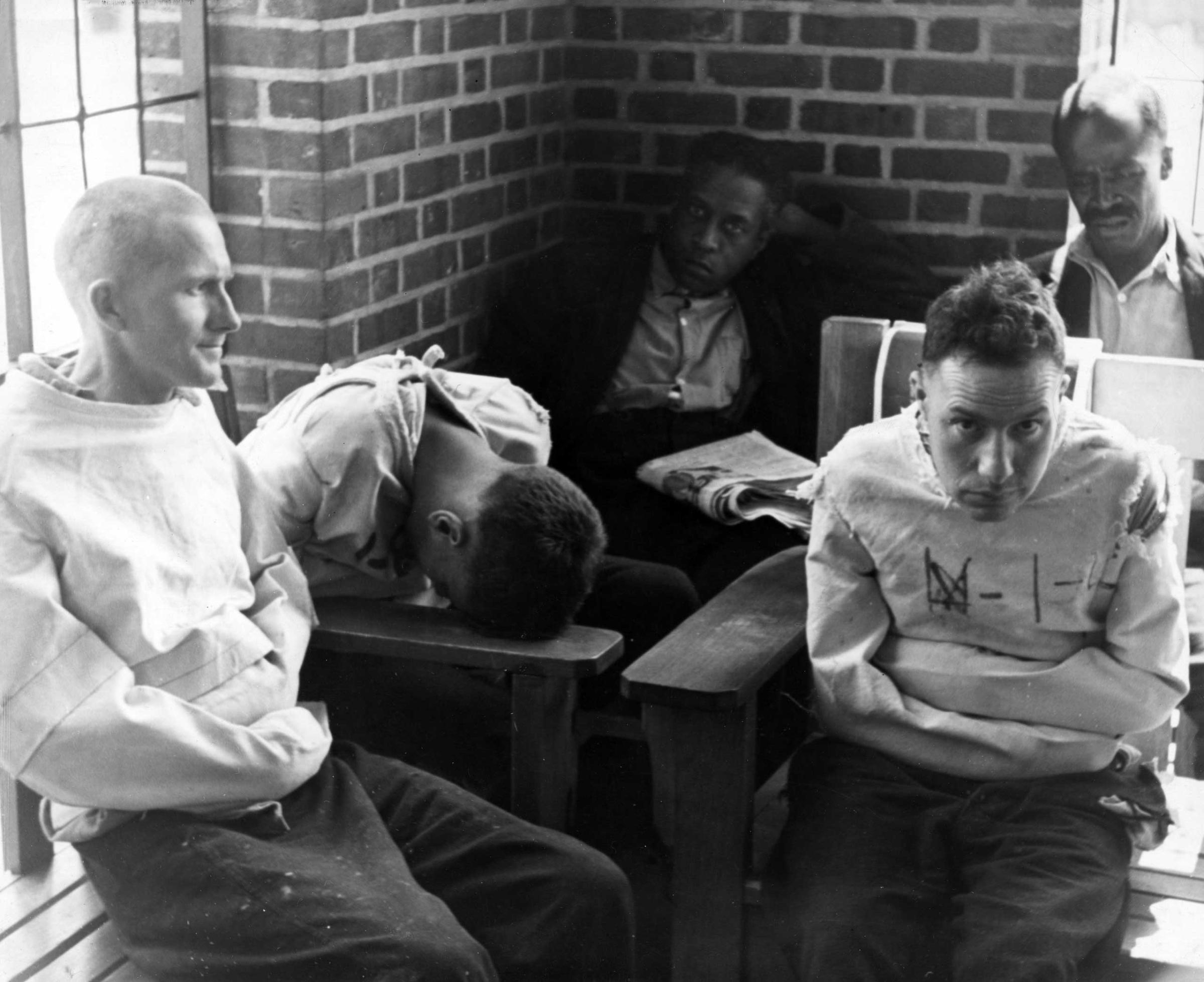

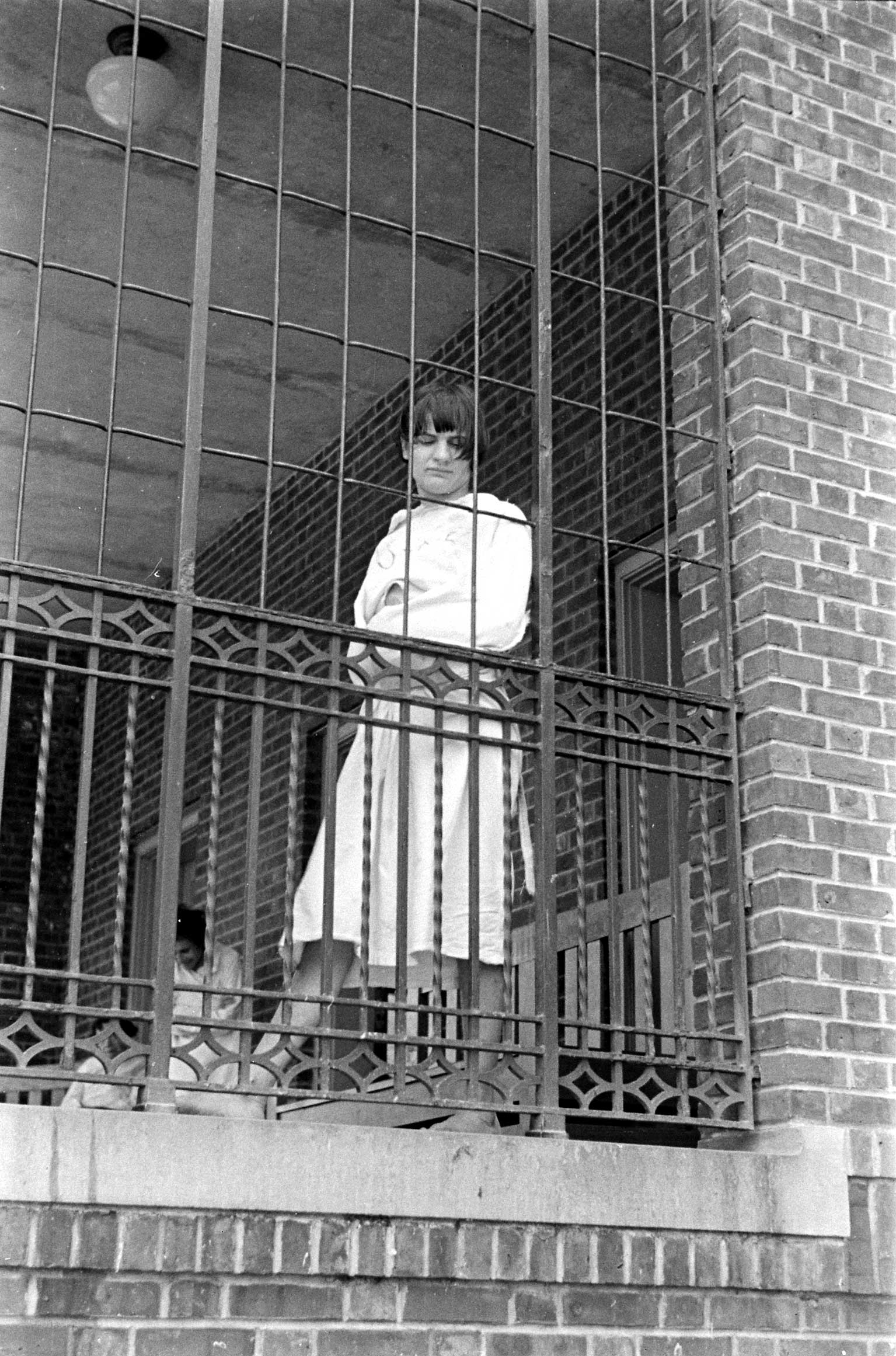

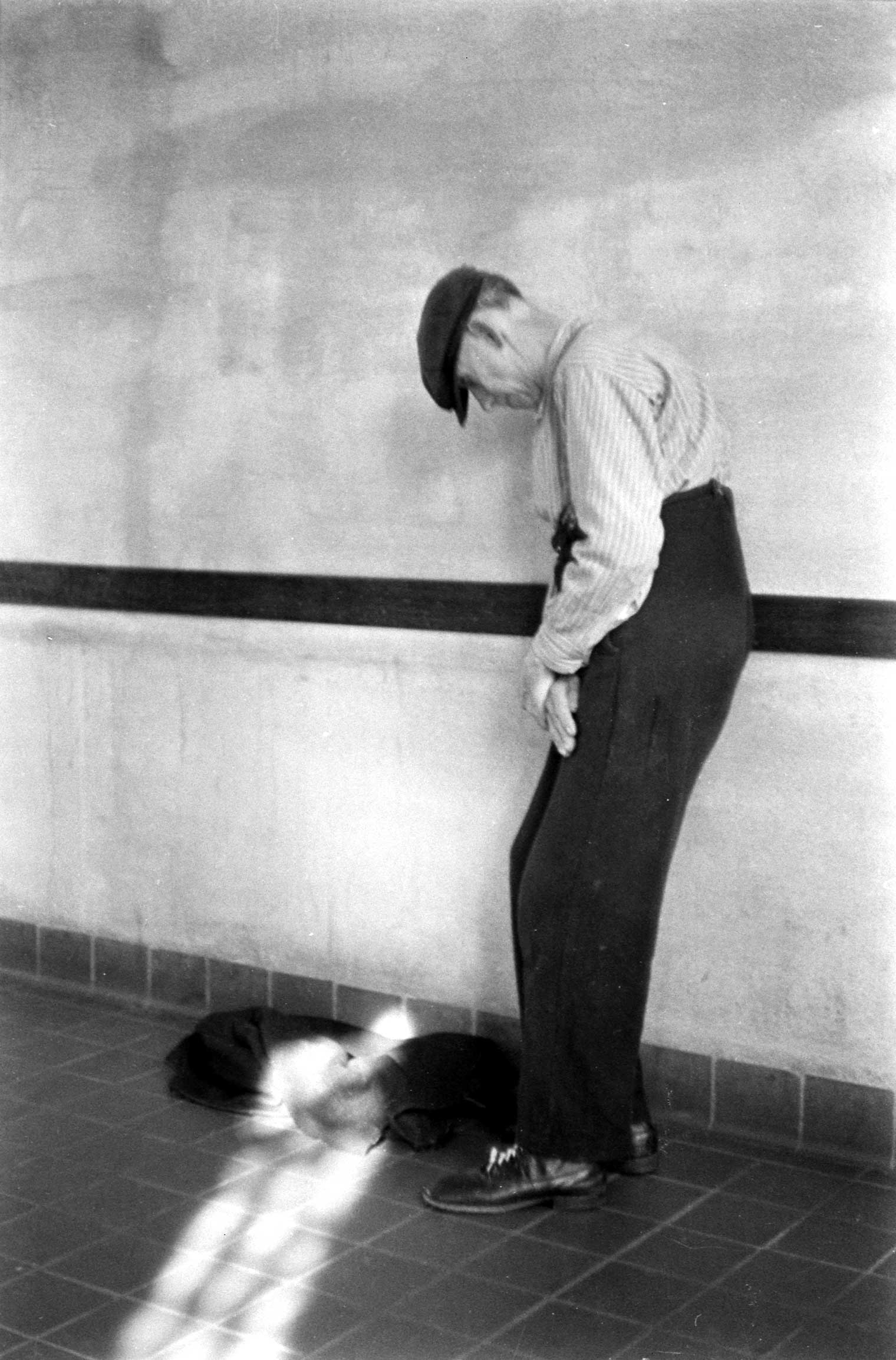

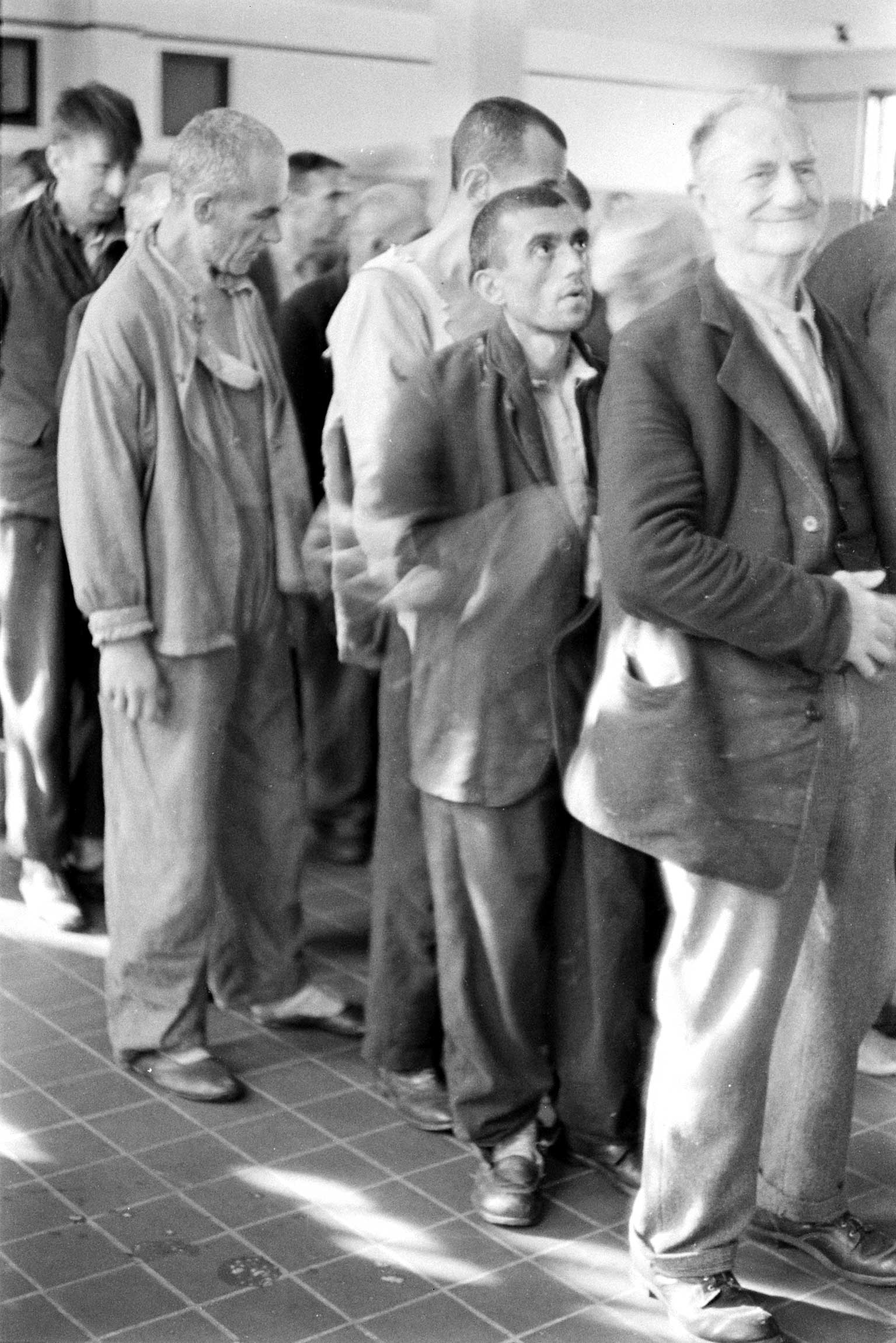

During the 1960s, Americans were horrified to learn about conditions within the state mental hospital systems, where patients were often abused and neglected, made to submit to dangerous medical procedures, or simply left live in squalid conditions for life. The popular backlash, made famous through books and movies such as One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, led to a general consensus against forcing anyone, under any circumstances, to receive psychiatric treatment against their will.

Now that belief is beginning to fade in large part because of simple budgetary math.

As it turns out, it’s just plain expensive for taxpayers to care for the small number of people with serious mental illnesses who refuse treatment and therefore end up homeless, incarcerated or draining the public coffers with multiple interventions and hospitalizations. At the same time, new psychiatric medications and methods have made it possible for people to get well without becoming long-term inpatients in the first place.

A new study, released this week by the Health Management Associates, a consulting firm, found that states and counties that have passed laws to allow local judges to order people into short-term psychiatric treatment spend substantially less money on treating mental illness than states and counties that don’t.

These programs, known as Assisted Outpatient Treatment are basically narrowly tailored safety-net programs designed to stabilize people with serious mental illnesses, and to keep them from ending up in a hospital, homeless or incarcerated. They require states and counties to pony-up a significant amount of cash in the short-term in order to build or maintain inpatient and outpatient facilities and organize a networks of mental health professionals, who are then legally responsible for them.

But that initial expense then ends up paying for itself, the Health Management Associates study finds. The outpatient program in New York City, for example, produced net cost savings of 47%, the study found. In the five counties surrounding New York, it saved 58%, and in Summit County, Ohio, it saved 50%, according to the study. In all three locations, the main cost-savings came from reducing the number of psychiatric hospitalizations. In New York City, the number of such hospitalizations dropped 40%; in Summit County, they dropped 67%. People who are assigned to Assisted Outpatient Treatment programs must fit certain criteria: they must have a serious mental illness, like schizophrenia or another disease with psychotic symptoms, and have a recent history of repeated violence or criminal activity.

Technically, Assisted Outpatient Treatment programs exist in 46 states across the country. But in most places, they are in name only. That’s partly because taxpayers and politicians have been unwilling to spend the cash to to get these pricey programs off the ground in the first place. And it’s partly because the idea itself—allowing judges to force people to receive psychiatric treatment against their will—remains deeply controversial.

Many patient rights advocates argue that any involuntary treatment whatsoever is an violation of a person’s civil rights. Others argue that such programs discourage people with serious mental illnesses from seeking treatment on their own. Daniel Fisher, a psychiatrist and the founder of the National Coalition for Mental Health Recovery, told TIME last year that he worries such programs represent “a slippery slope” back to the kind of mass institutionalization seen in the 1940s and ’50s.

But in many parts of the country, including liberal bastions such as the San Francisco Bay Area, lawmakers are beginning to embrace AOT programs on both fiscal and humanitarian grounds. Although people with symptoms of serious mental illness make up only about 4% of the U.S. population, they account for 15% of state prisoners, 24% of jail inmates and as much as 30% of the chronically homeless population, according to government records. People with serious mental illnesses are also nearly 12 times as likely as the average person to be the victim of a violent crime, like rape, and as much as eight times as likely to commit suicide.

The Health Management Associates study, which was presented to the Treatment Advocacy Center, an organization dedicated to promoting Assisted Outpatient Treatment programs, is the latest in a long line of similar studies that have attempted to quantify the cost of not treating the seriously mentally ill.

Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, has estimated that the total cost of non-treatment to the government—including things like Medicare, Medicaid, disability support and lost productivity—is as much as $317 billion per year. Other studies have suggested that it costs federal, state and local governments $40,000 to $60,000 to care for a single homeless person with a serious mental illness. There are roughly 250,000 mentally ill homeless people in the U.S. today.

While no single study has looked at the cost of caring for all U.S. inmates with serious mental illnesses, some state and local studies have found that it costs roughly twice as much to incarcerate an inmate with a mental illness as one without and can run states up to $100,000 per inmate per year. There are an estimated 356,000 seriously mentally ill inmates in the U.S. today.

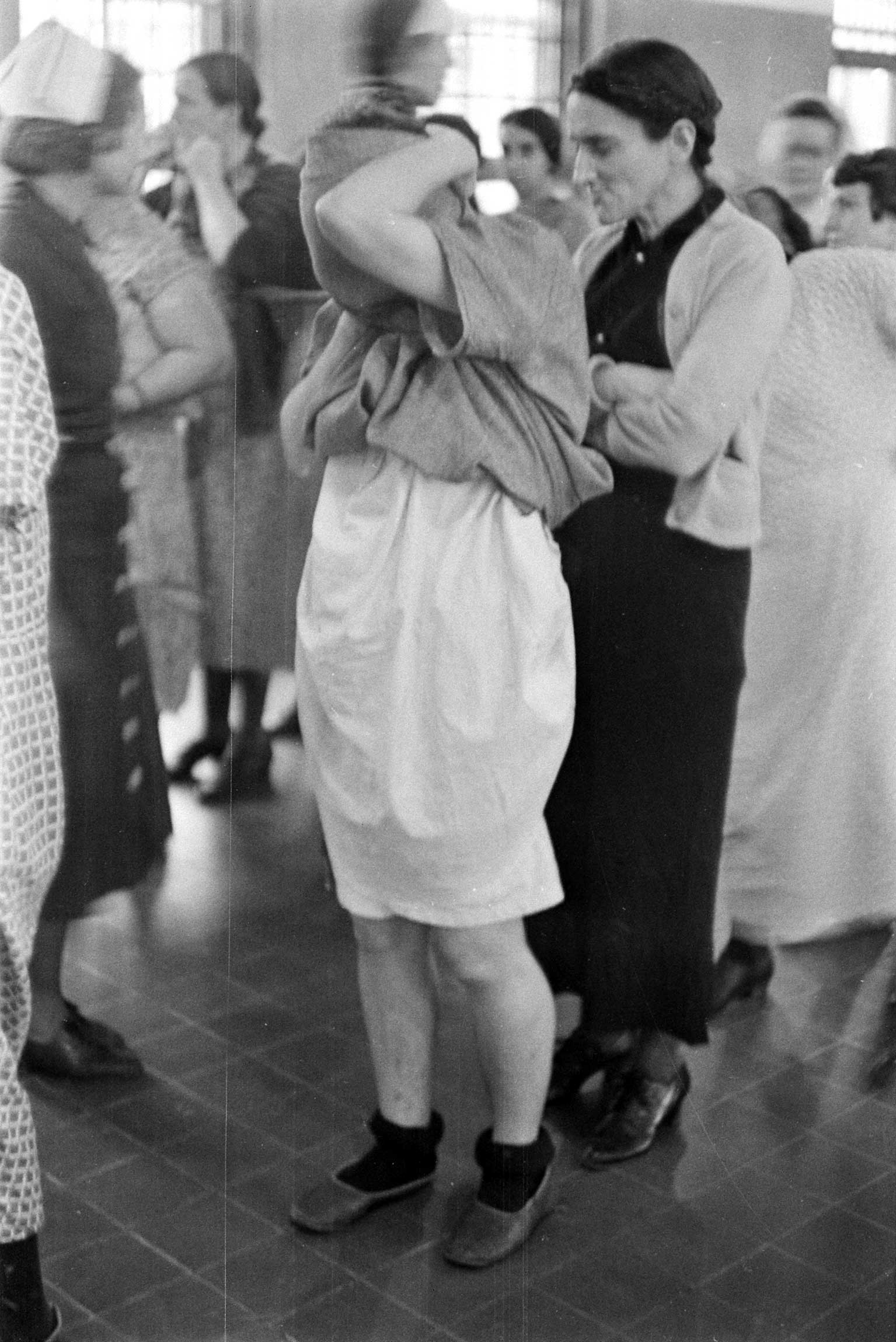

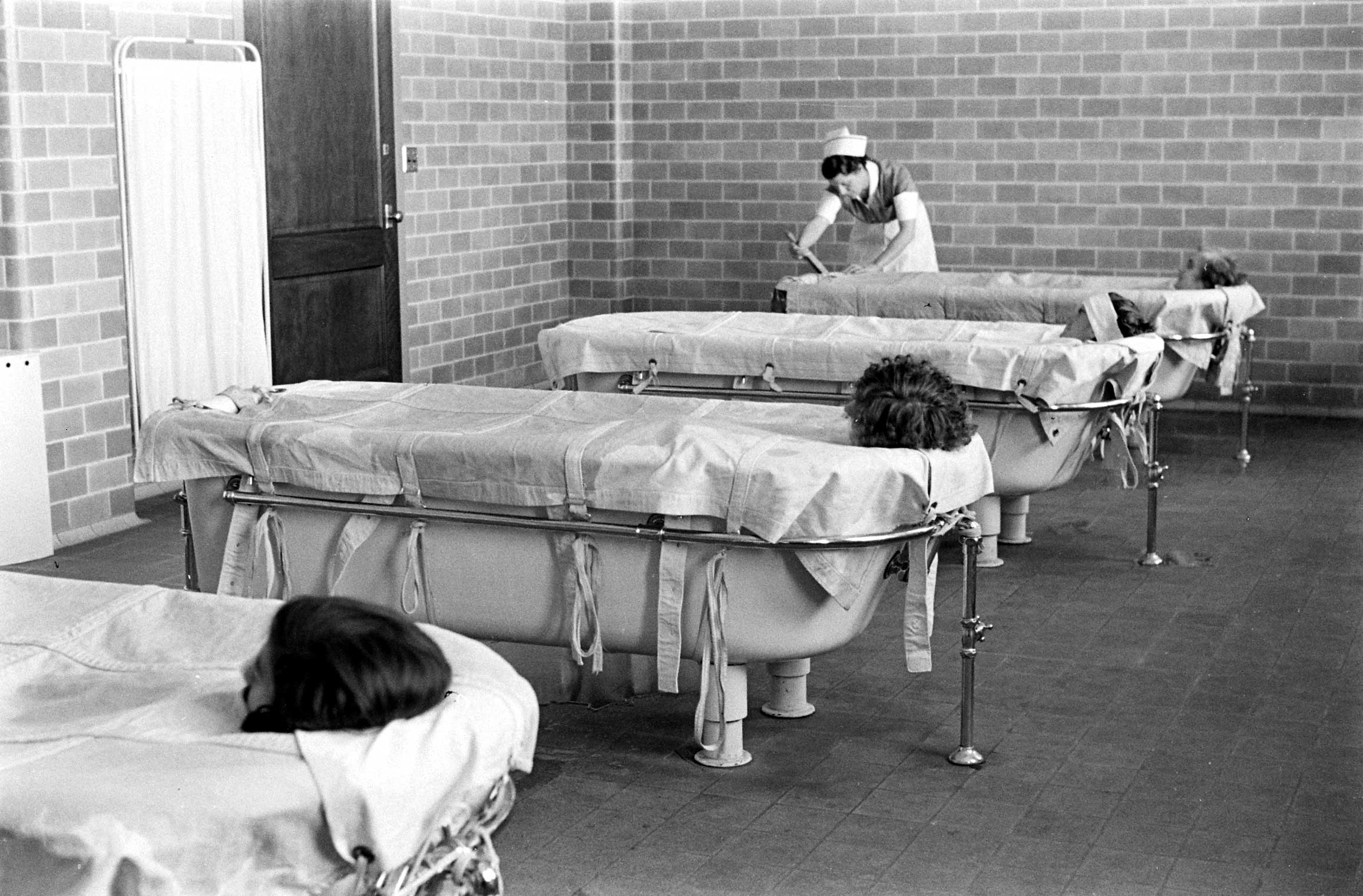

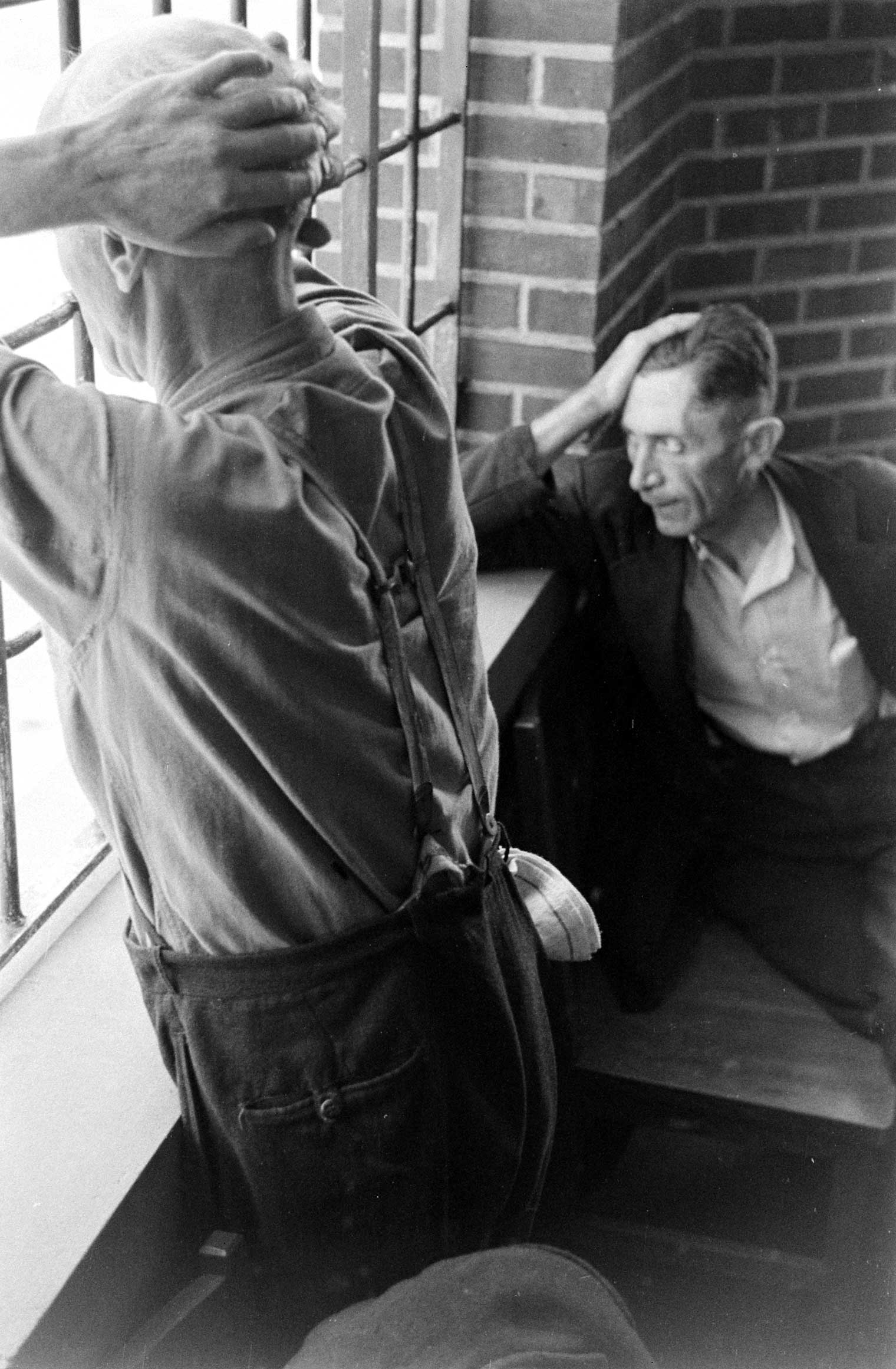

Strangers to Reason: LIFE Inside a Psychiatric Hospital, 1938

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com