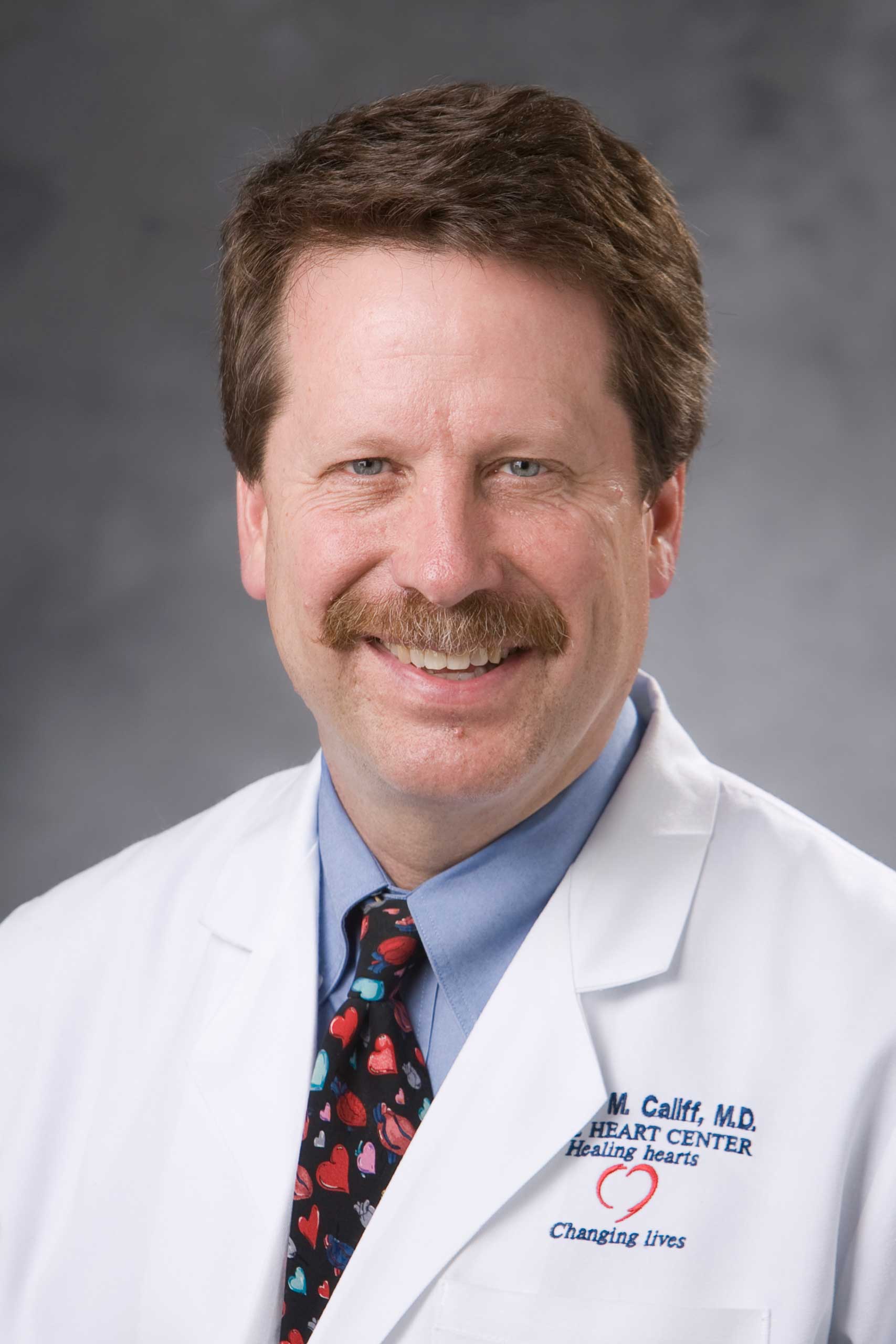

Last May, Duke University’s Vice Chancellor for clinical research, Dr. Robert Califf, told an audience of executives that the American system for developing drugs and medical devices was in crisis. Using slides [pdf] developed by Duke’s business school, he said the system was too slow and too expensive, and required disruption and transformation. Towards the end of his talk, he put up a slide that identified a key barrier to change: regulation.

Such views are not uncommon in industry, academic research and on Capitol Hill, but they are noteworthy coming from Califf because he could soon be America’s top regulator overseeing the safety and efficacy of the country’s drugs and medical devices. Califf is already set to become deputy commissioner at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) next month. Now sources familiar with the process tell TIME he is on President Barack Obama’s short list to run the agency following this month’s announcement that its long-serving commissioner, Margaret Hamburg, will step down in March.

The White House declined to comment on pending personnel decisions, but word that Califf is in contention for the top spot at the FDA comes at a key moment. The agency faces potentially dramatic changes this year as Congress prepares to rewrite many of the rules for how drugs and medical devices are reviewed and tested for safety and efficacy. Califf is widely respected in the public and private sectors, but his candidacy is seen by some as a threat to the independence and authority of the FDA, thanks to his views on the need to accelerate change and his deep financial and intellectual ties to the pharmaceutical and medical device industries.

Califf says his salary is contractually underwritten in part by several large pharmaceutical companies, including Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Novartis. He also receives as much as $100,000 a year in consulting fees from some of those companies, and from others, according to his 2014 conflict of interest disclosure [pdf]. In an interview with TIME, Califf estimates that less than half of his annual income comes from research money provided by the pharmaceutical industry, though he says he is not certain because he doesn’t tend to distinguish between industry and government research funding. He says he is divesting his holdings in two privately-held pharmaceutical companies he helped get off the ground.

Califf says such collaboration, not just between industry and academia, but with government, too, is the way of the future. “The greatest progress almost certainly will be made by breaking out of insular knowledge bases and collaborating across the different sectors,” Califf says. He says there is “a tension which cannot be avoided between regulating an industry and creating the conditions where the industry can thrive, and the FDA’s got to do both.” He says it would be “useful to have someone [leading the FDA] who understands how companies operate because you’re interacting with them all the time.”

Diana Zuckerman, President of the National Center for Health Research, which advocates for FDA regulatory authority, says such ties “should be of great concern.” Dr. Califf is “a very accomplished, smart physician who’s been an important name in the field,” Zuckerman says, but his “interdependent relationships” raise questions about his “objectivity and distance.” She cites several studies suggesting the medical products industry uses such ties to influence the behavior and decision making of doctors and researchers, even when the scientists don’t realize it.

The tension over Califf’s collaboration with industry gets to the heart of the future of the FDA at a pivotal moment. While FDA defenders see the collaboration as a threat to its independence, others see close relationships between government, industry and academia as the model for the future. Califf heads a successful and powerful clinical research program, the Duke Translational Medicine Institute, which brings together industry drug researchers, academic scientists and federal regulators to speed drug development and approval. Califf estimates 50-60% of its $320 million in annual research funding comes from industry.

Capitol Hill is considering codifying parts of that collaborative model for the FDA. The powerful Energy and Commerce Committee in the U.S. House of Representatives recently introduced a draft bill called 21st Century Cures, which would loosen the drug approval and post-market oversight process. Califf says because the bill is still in draft it is too early to pass an overall judgment on it but he says, “I support a lot of the concepts in the bill.”

In the Senate, the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) committee has begun work on its own bill, with committee chairman Lamar Alexander declaring, “It takes too long and costs too much to develop medical products.” In a report paving the way for his legislation, Alexander concluded the FDA has grown too large, has fallen behind scientific innovation and threatens American leadership in biomedical innovation. Reform efforts in the Senate may be aided by the support of liberals like Elizabeth Warren who back looser regulations on the medical device industry.

The FDA uses a model for drug testing and oversight largely developed in the early 1960s, with phased trials before drugs and devices are approved for sale to ensure they are safe and effective, and “post-market” studies afterwards to monitor them. Over time, the agency has come to rely on the medical product industry for more than 60% of its budget for post-market monitoring. Accused of regulatory capture by those who see undue industry influence, the FDA has faced attacks from both sides.

That means the FDA has few defenders and will rely heavily on its next commissioner to stand up for it in public and on Capitol Hill. “This is a very dangerous time for the agency,” says Zuckerman of the National Center for Health Research, “It’s under fire in a way that is unprecedented in the last 20 years.”

Califf’s supporters point out that he is among the ten most cited medical authors in America, and that he has spent his career as a clinician helping patients. Regarding the danger of regulators being “captured” by their interactions with industry, Califf says, “The difference between capture and collaboration towards improving human health is a pretty big difference.”

The White House has set no time frame for its decision on Hamburg’s replacement. It has announced the acting commissioner will be Dr. Stephen Ostroff, a scientist and long-time official at the Health and Human Services department, when she steps down in March.

See Washington D.C. as a Winter Wonderland

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com