Reporting in the journal Nature, scientists describe a new way to potentially block HIV from infiltrating healthy cells. Such interference is key to protecting people from HIV infection, but most efforts so far haven’t been successful.

This time, however, may be different. Michael Farzan, professor of infectious diseases at Scripps Research Institute, and his team used a gene therapy technique to introduce a specific HIV disruptor that acted like gum on HIV’s keys. Once stuck on the virus’s surface, the peptide complex prevents HIV from slipping into the molecular locks on healthy cells. Because the gum isn’t picky about which HIV strain it sticks to—as long as it’s HIV—the strategy works against all of the strains Farzan’s group tested in the lab, including both HIV-1 and HIV-2 versions that transmit among people, as well as simian versions that infect monkeys. In lab dishes containing the virus and human and animal cells, the disruptor managed to neutralize 100% of the virus, meaning it protected the cells from getting infected at all.

MORE: The End of AIDS

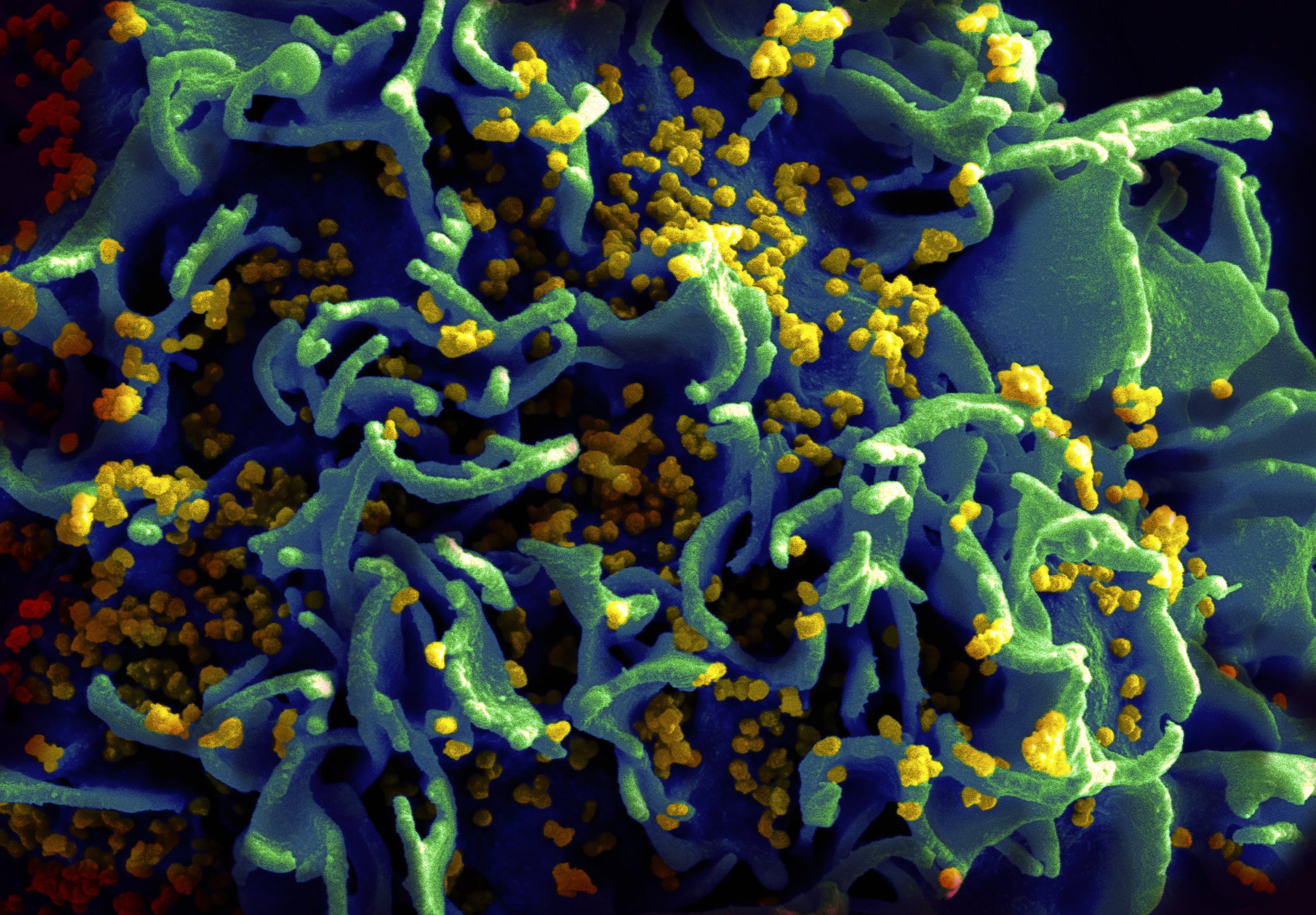

The strategy is based on what HIV experts know about how the virus infects healthy cells. HIV looks for a protein, or receptor on immune cells called CD4, which serves as the lock, and uses a specially designed portion of its own viral coat made up of three proteins as the key. Once HIV finds its target and the match is made, the virus changes its shape to better slip inside the healthy cell, where it takes over the cell’s machinery and churns out more copies of itself. Farzan’s gum, called eCD4-Ig, not only seeks out these parts of the key and renders them useless, but by glomming onto the key, also causes the virus to morph prematurely in search of its lock. Once in lock-finding mode, the virus can’t return to its previous state and therefore is no longer infectious.

The encouraging results suggest that eCD4-Ig could provide long-term protection against HIV infection, like a vaccine; in four monkeys treated with gene therapy to receive eCD4-Ig, none became infected with HIV even after several attempts to infect them with the virus. The protection also seems to be long-lasting. So far, the treated monkeys have survived more than a year despite being exposed to HIV, while untreated control monkeys have died after getting infected.

MORE: This Contraceptive Is Linked to a Higher Risk of HIV

The strategy, while promising, is still many steps away from being tested in people. Farzan used a cold virus to introduce the eCD4-Ig complex directly into the muscle of the animals, and it’s not clear whether this will be best strategy for people. Previous gene therapy methods have led to safety issues, and concerns have been raised about controlling where and how much of the introduced material gets deposited in the body. It may also be possible to give the peptide as an injection every few years to maintain its anti-HIV effect.

MORE: HIV Treatment Works, Says CDC

Farzan anticipates that if proven safe, the strategy could help both infected patients keep levels of HIV down, as well as protect uninfected, high-risk individuals from getting infected. But many more tests will need to be done before we might see those results. Four monkeys can provide valuable information, but can’t answer questions about safety and efficacy with any confidence. “Things change when we get to humans and when we get to larger numbers,” he says. “But the data in monkeys are as encouraging as one could hope.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com