The Oklahoma state legislature passed a bill this week directing its education board to “adopt a certain United States History program” that would be offered to students instead of the Advanced Placement course on the same topic, which legislators have accused of representing the nation in a negative light.

It’s the latest round in an ongoing fight over changes made to the A.P. U.S. History program for this school year — Colorado drew protests over just such a fight this past fall, and, as ThinkProgress reports, similar fights have sprung up in several other states — and a perfect illustration of why the matter is unlikely to be resolved any time soon.

Here’s what the Oklahoma bill says: the new curriculum must include many of the “founding documents” of the nation, as well as those relating to the “foundation or maintenance of the representative form of limited government, the free-market economic system and American exceptionalism”; schools that stick with the A.P. curriculum will lose funding for the program.

The list of particular documents that Oklahoma students must study includes some obvious items — the Mayflower Compact, the Bill of Rights — as well as several unarguably important but perhaps less foundational documents, like Ronald Reagan’s speech on the 40th anniversary of D-Day.

Although the legislators have a variety of issues with the A.P. program, Tulsa World reported that the bill’s author Rep. Dan Fisher said during debate on the legislation that he targeted the U.S. History course because the new curriculum doesn’t give enough weight to American exceptionalism.

But what would it mean for a curriculum to focus on American exceptionalism? The idea seems easy enough to grasp — in 1988, TIME defined it as “the divine dispensation that the nation thought it enjoyed in the world”; in other words, the idea that America is special — but, though it’s nearly as old as the nation to which it refers, its meaning is still up for debate.

For one thing — though versions of the concept go back to the founding of the United States and the Puritan notion of the “city on the hill” — the actual phrase has murky origins. It’s often attributed erroneously to Alexis de Tocqueville, the 19th-century French sociological observer of American mores, who noted the ways in which the new nation differed from its old-world origins. Others have traced the coinage to the unlikely source of Joseph Stalin, who used it to explain why America was slow to take to Communism (which, he naturally thought, was a bad thing), though the myth that he came up with the wording has been debunked with evidence that the word “exceptionalism” was in use at least as early as the Civil War era.

In recent years it’s been getting a lot more play — Google shows growth since around 1950, with a sharp uptick in the last two decades, starting right around when Seymour Martin Lipset wrote the book American Exceptionalism: A Double-Edged Sword — and President Obama, often in response to claims that he doesn’t think his country is special enough, has become one of its most vocal boosters. “[Having a global childhood] has reinforced my belief in American exceptionalism,” he told TIME in 2008. “One of the things that happens when you live overseas is you realize how special America is–our values, our ideals, our Constitution, our rule of law, the idea of equality and opportunity. Those are things that we often take for granted, and it’s only when you get out of the country that you see the majority of the world doesn’t enjoy those same privileges.”

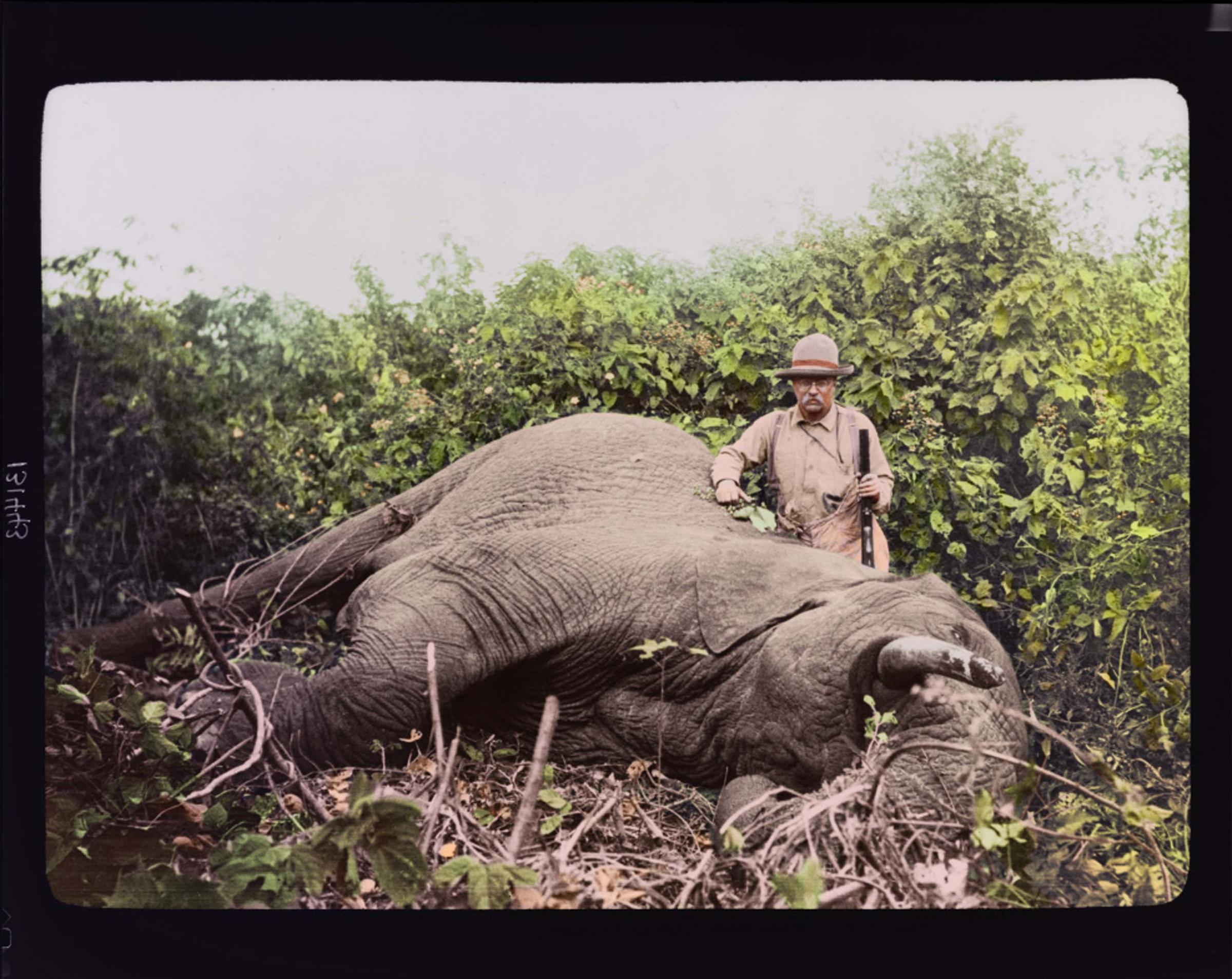

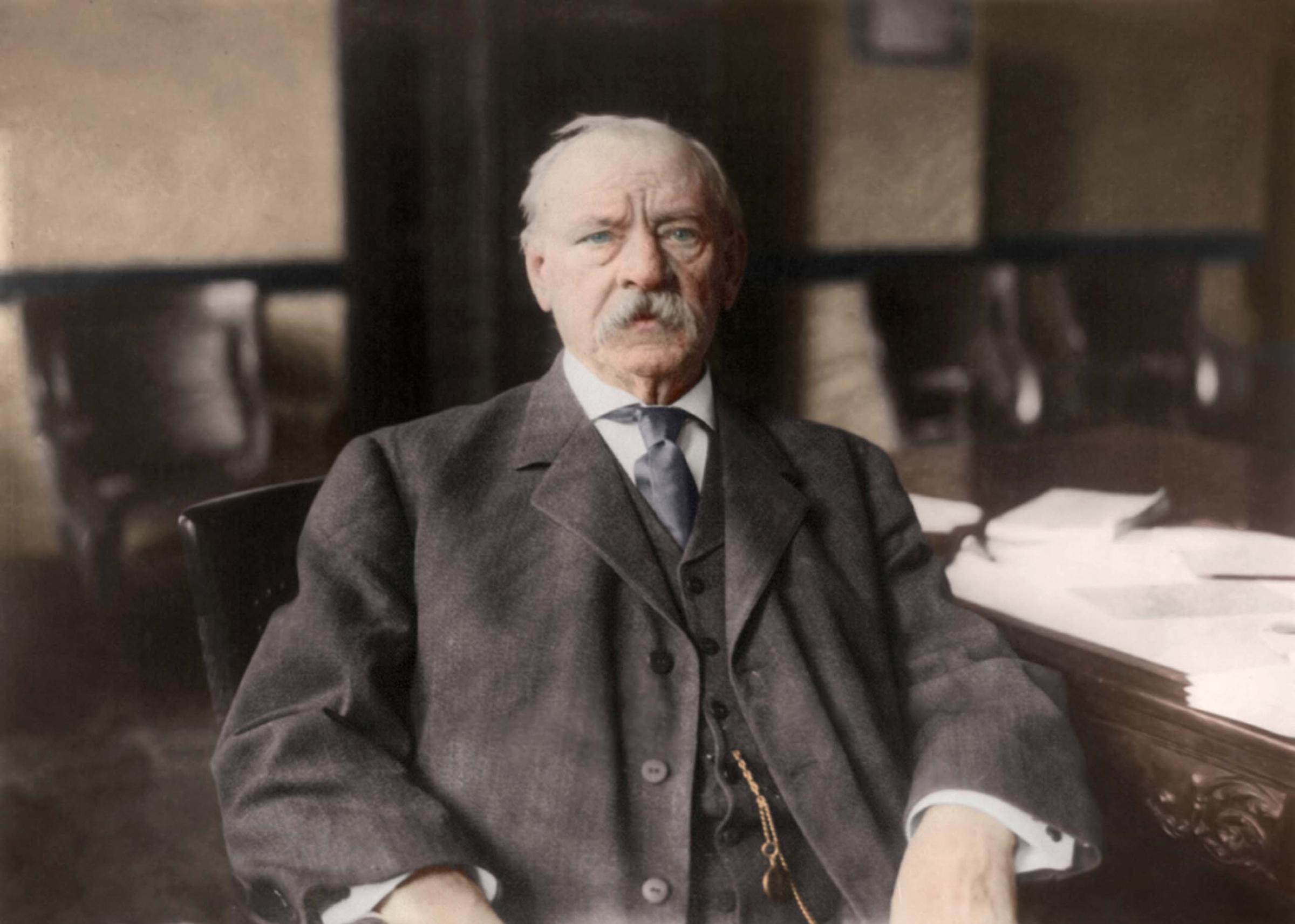

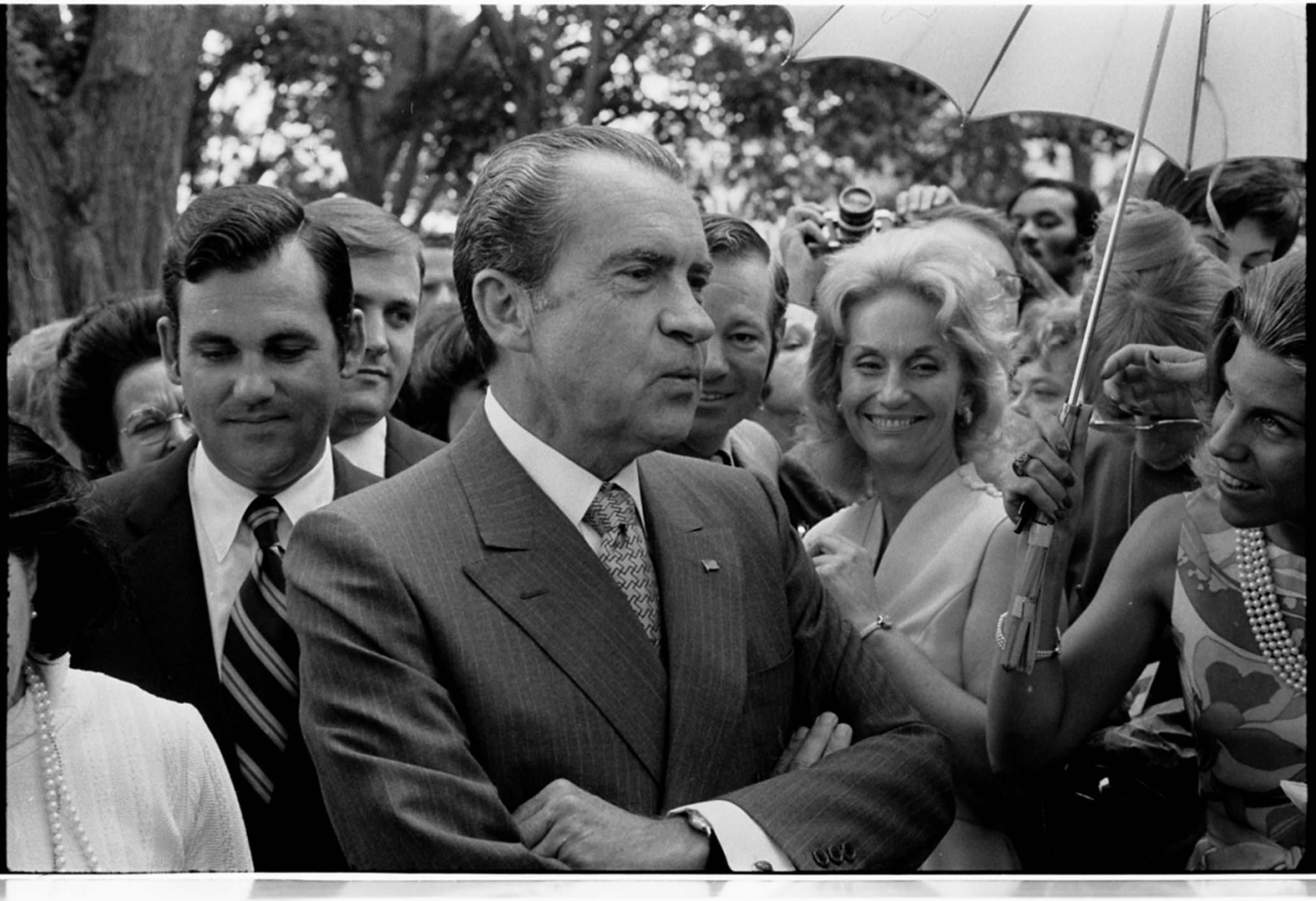

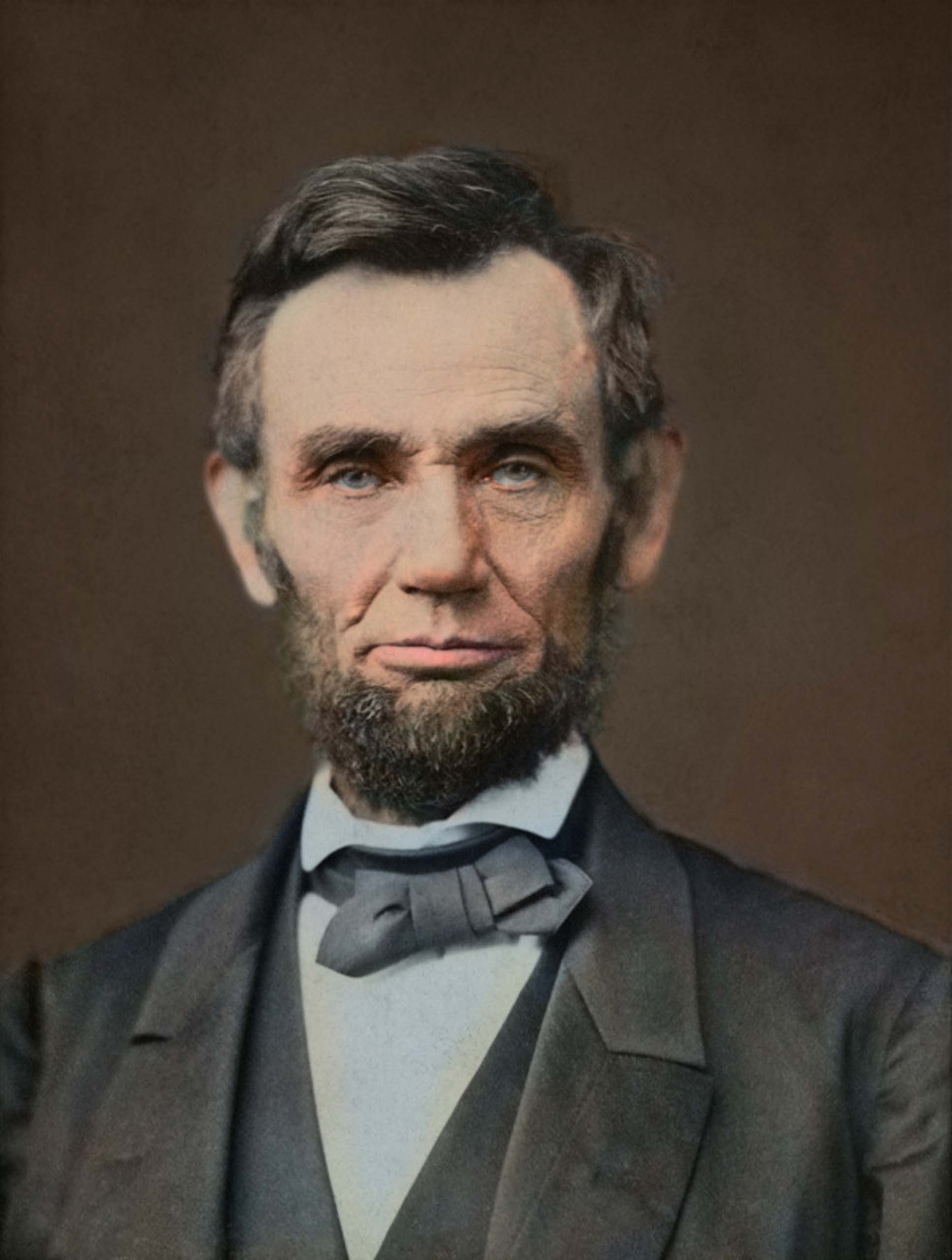

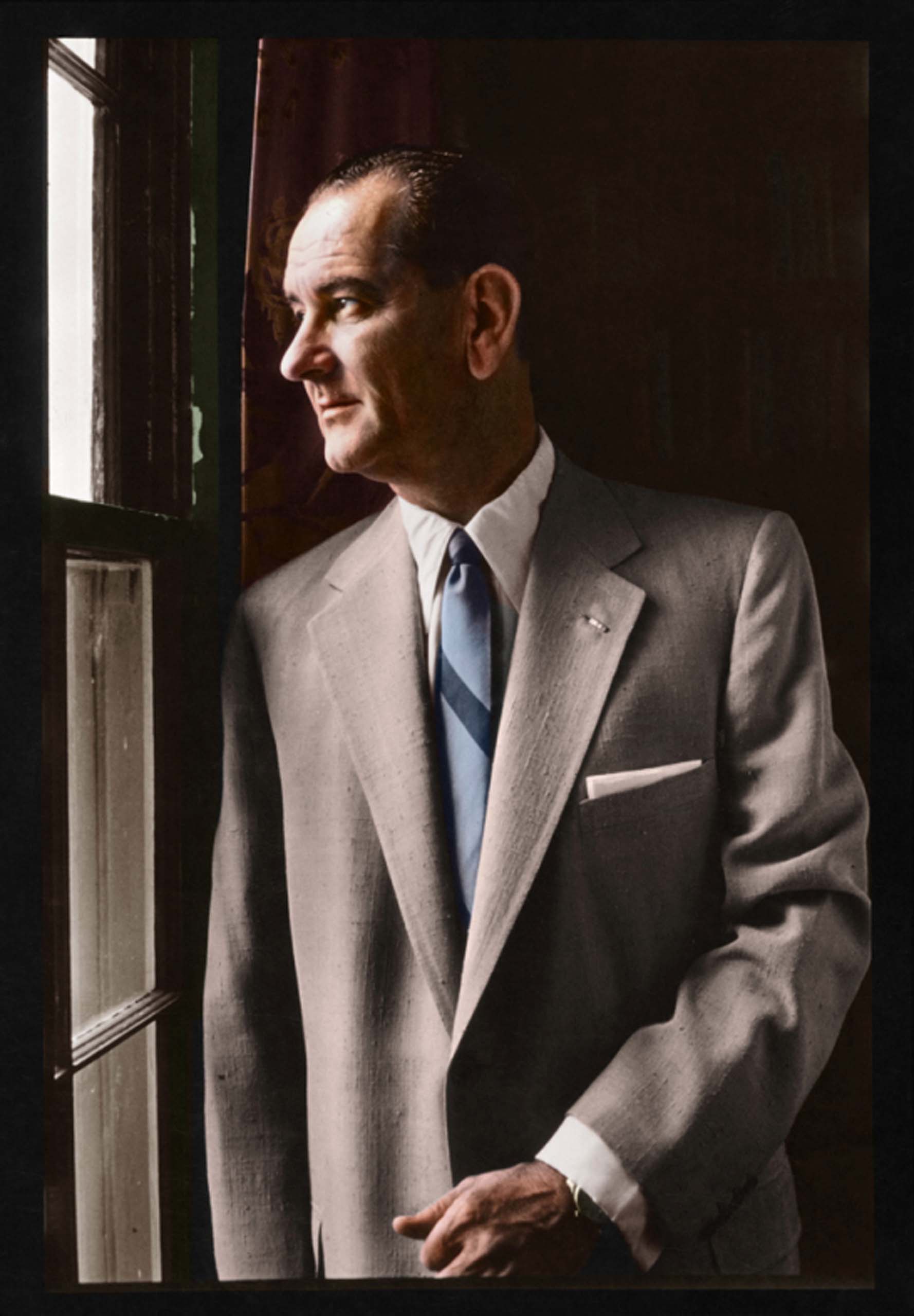

Bringing Color to Presidents Past

![Abraham Lincoln, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing front. Date Created/Published: [photograph taken 1863 Nov. 8; printed later and c1900]. Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/presidents-past-14.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

And yet, as pointed out by a 2012 essay by James W. Ceaser in the journal American Political Thought, there are multiple ways to understand the phrase. For one thing, though the word “exceptional” has positive overtones, it can also be a neutral description of difference; he writes that, in terms of sociology, the latter is more common and can be used to discuss the negative qualities of a culture that make it an exception to the norm. (For example: the Communist view that America is exceptional due to its failure to inspire a workers’ movement.) And secondly, he writes, the dominant idea that the nation has a special mission can mean a variety of things, from a religious sense of purpose to a political mission to spread democracy.

During the debate in Oklahoma, a representative of the College Board objected that the claim that the curriculum ignored exceptionalism was “not true.” After all, he pointed out, the framework of the course doesn’t actually dictate which moments or ideas can be used to teach its “thematic learning objectives” (identity; work, exchange and technology; people; politics and power; America in the world; environment and geography; and idea, beliefs and culture).

But whether the accusation is “true” depends, ultimately, on how one views American exceptionalism. Is it a purely academic matter of historical ideology? A matter of mere distinction? Or a matter of being not just different, but also special and better? It’s a tough question, but as the fight over school curricula moves forward, one group of Americans is left uniquely positioned to debate it: high-school students.

Read next: The Myth of Neutrality in American Sporting Culture

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com