By now you’ve heard just about every opinion about measles—thanks to the outbreak which, aided by the unvaccinated, has spread from Disneyland to seven states, infecting 114 people, and sending about one in seven to the hospital.

But two opinions stand out to me. Jay Gordon, a California pediatrician, told the CBS Evening News that “measles is almost always a benign childhood illness.” A few days later, Kentucky senator and ophthalmologist Rand Paul, speaking about vaccines to talk show host Laura Ingraham, said: “I think most of them ought to be voluntary.”

You heard right: in the middle of a measles outbreak, doctors are raising doubts about the value of a proven, lifesaving public health measure.

For my part, I agree with Art Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University, who wrote in the Washington Post on Sunday that doctors who are as manifestly irresponsible as Gordon and Paul ought to have their medical licenses revoked.

I draw my conclusions from decades of scientific evidence that vaccines save lives. But the strength of my feelings comes from my experiences working with the kids on Ward N2A at the King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban, South Africa, where measles was anything but a “benign childhood illness.”

When I was a medical student at Oxford in the mid-1980s, I spent two months studying pediatrics in Durban. Under the then-Apartheid regime, the hospital, a maze of run-down brick buildings sprawled behind the city’s shipyards, served blacks from every corner of a North Carolina-sized area that encompassed the province of Natal, along with what were then the tribal homelands of KwaZulu and Transkei.

This was the era before HIV/AIDS exploded in southern Africa, and diarrhea and infectious diseases were the main killers of the kids who packed into the understaffed pediatric ward with its peeling paint. But among these diseases, measles was king of the killers.

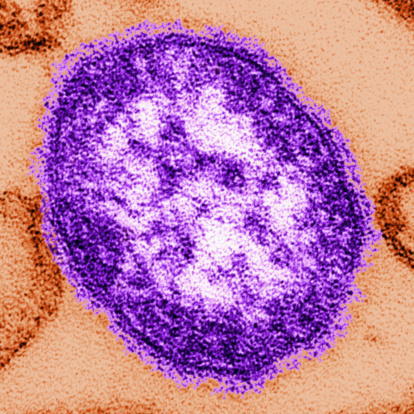

Measles is hugely contagious. It’s a respiratory virus spread by coughing and sneezing, and it enters the body through the mouth, nose or eye. After that, in an unvaccinated child, it takes up residence in the tonsils and adenoids, which are glands in the throat. From there, it spreads further, in some cases marching down the windpipe and into the lungs.

If measles gets a foothold in the lungs, it becomes life-threatening, filling the multitudinous, tiny air sacs called alveoli with fluid and pus. In a cruel twist, measles also causes lung cells themselves to proliferate, creating still more sludge in what should be air spaces. If you look at a microscope slide of a lung taken from the autopsy of a victim of measles pneumonia, you won’t see many white spaces that are alveoli, because this soup of infection obliterates them. This massive pneumonia happens most often in malnourished children or kids with diseases, such as leukemia, lymphoma, and HIV/AIDS, that weaken their immune systems. Once this raging viral infection is established, bacteria will often move in, too, adding what is frequently the death knell to an already-perilous situation.

Anyone could pick out the kids with measles on Ward N2A because they were under oxygen tents. They should have been on respirators, but at the King Edward, there were hardly any available. I would watch their tiny, skinny rib cages as they strained so hard to breathe that the flesh between their ribs was pulled visibly inward with each hard-won breath. There was little that we medics could do for them, except hold their hands.

Anywhere in the world, one in 20 kids who get measles will end up with pneumonia. But on Ward N2A, those numbers were much higher, because the virus had a big head start. The kids who made it to the hospital mostly came from desperately poor slums and villages. They were almost uniformly malnourished, which makes measles more severe. And the little ones whose immune systems weren’t yet mature were the most vulnerable of all. It was a common occurrence to find a toddler, too young to be immunized even if vaccine was available, dead under his or her oxygen tent.

So when I hear people like Jay Gordon, who has been writing “personal belief exemptions” for parents who don’t want to have their children vaccinated, argue that measles is a benign childhood illness, I feel angry. And not only on behalf of those South African toddlers who for the lack of a 24-cent vaccine never had the chance to grow up — or the 400 people, almost all of them young kids, who died every day in 2013 from measles. I feel angry on behalf of the babies in a Chicago day care who have come down with measles because they are too young to be vaccinated. I feel angry for every American with lymphoma or leukemia or HIV/AIDs, for whom a brush with an unvaccinated person with measles could mean the beginning of the end. Measles can also mean the end of the beginning: contracting the disease during pregnancy results in an increased incidence of miscarriages, stillbirths and premature labor.

The facts are these: measles vaccine has an excellent, decades-long track record of safety and effectiveness and we must protect children and adults who, for legitimate medical reasons, can’t be vaccinated. The spurious link of the vaccine to autism has been soundly disproven, and its purveyor, British physician Andrew Wakefield, discredited and stripped of his medical license. Yet, in 2014, there were 644 measles cases in the United States – more than in any year since 2000, when home-grown cases were declared eliminated. During the same period, thanks to improving rates of vaccination abroad, the number of deaths from measles globally fell by 75%.

It’s time that medical licensing bodies began ejecting physicians who endanger the public health with their pronouncements undermining proven, vital vaccines. It’s time that the 20 US states that allow them tighten their personal belief exemptions, some of which are famously lax. And it’s time that non-vaccinators had a hard look at the risks that their choices pose not only to their own children but to some of the most vulnerable people among us—so many of them, like the patients in Durban I still remember, young children.

As an Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fellow at New America, Meredith Wadman is writing a book about a unique group of cells that are widely used in scientific research and for making vaccines that have immunized hundreds of millions of people. She has covered biomedical research politics from Washington for 17 years, writing for publications including Nature, Fortune, the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. This piece was originally published in New America’s digital magazine, The Weekly Wonk. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox each Thursday here, and follow @New America on Twitter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com