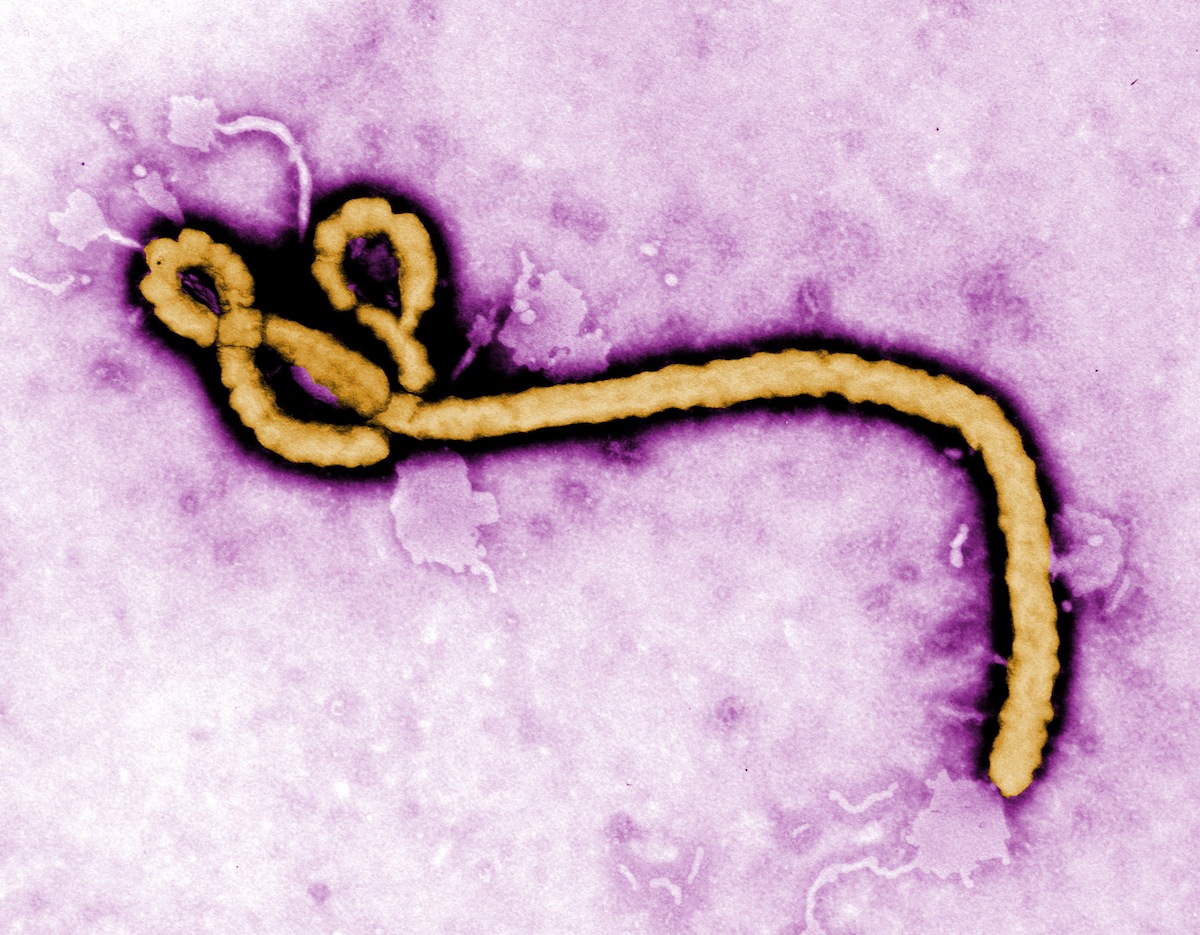

This post is in collaboration with The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress, which brings together scholars and researchers from around the world to use the Library’s rich collections. The article below was originally published on the Kluge Center blog with the title Ebola, Colonialism, and the History of International Aid Organizations in Africa.

Historian Jessica Pearson-Patel was one of fifteen emerging scholars to participate in the Eighth International Seminar on Decolonization hosted by the Kluge Center and organized by the National History Center. A scholar of global health and colonial Africa, she has observed the current Ebola outbreak with an eye toward the history of health organizations on the continent. She sat down with Jason Steinhauer to examine the history behind international public health organizations in Africa and the historical parallels between Ebola and other transnational diseases.

During this Ebola outbreak, Western media coverage has devoted much attention to the Western and international aid organizations that travel or send aid to West Africa. Which organizations have been on the ground in West Africa already, and which are newly arrived to combat this particular epidemic? Is there a historical distinction between them?

The two health organizations that have played the most important roles in the current Ebola epidemic are the World Health Organization, founded in 1946, and Doctors without Borders, founded in 1971. But international health organizations in Africa have a long and complicated history. The history is made all the more complex by the fact that when some of these organizations began in the post-World War II era, much of the African continent was still ruled by European colonial administrations.

The World Health Organization (WHO) was one of the first international health organizations to play an important role in Africa. The WHO was founded after the war as an autonomous organization linked to the United Nations. Its central organization created six regional offices that were intended to better respond to health concerns on the ground around the world: Europe, Southeast Asia, the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Western Pacific, and Africa. The creation of the Africa office was highly contested. Africa had some of the most pressing health problems of all the regions, but colonial officials feared that because the organization was affiliated with the U.N., international medical personnel could potentially bring anti-colonial ideologies with them, in addition to vaccines and medical equipment. Colonial governments did what they could to stall the work of the WHO and also created their own health organizations. None of these colonial health organizations still exist, but the efforts to limit the WHO’s reach in Africa certainly shaped its evolution there.

Médecins sans Frontières, or Doctors without Borders (MSF), was founded after African decolonization, in the wake of the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970). MSF was able to escape many of the colonial constraints faced by the WHO owing to the fact it was created 25 years later.

Many other governmental and non-governmental health and humanitarian organizations exist today, and are involved in the fight against Ebola. But most do so in coordination with WHO and MSF.

It sounds as though the history of health organizations is intimately linked to the history of colonialism–as is the ideology and rhetoric used by these organizations.

Yes. Initial health projects in colonial Africa were directed at diseases that primarily affected Europeans. This was an attempt to facilitate European colonial rule. Hospitals were built to treat European patients. Ports were sanitized. As colonial powers increasingly came under local and international pressure to justify their actions in Africa, health services for Africans became a way to justify imperial rule in the context of a “civilizing mission.” Health efforts shifted to vaccinating Africans against diseases like yellow fever, developing mobile health teams to service patients in rural areas, and constructing “modern” maternity hospitals where African women could give birth in European-style facilities. Health services in Africa in the early 20th century were intimately linked to the project of colonial conquest and domination and the prevailing rhetoric was one of “civilization.”

After the founding of the United Nations in 1945, many colonial powers–especially the French–reframed their discourse about health in terms of “development,” rather than “civilization.” It is this rhetoric of development that came both from postwar international organizations and postwar colonial governments that we see today–although “development” certainly can have a different valence in the context of independent African countries.

What was the impetus for the WHO’s creation in 1946? What about the post-war moment contributed to its forming?

Organizations such as the WHO are relatively recent phenomena. While the adage “disease knows no boundaries” has been generally acknowledged for centuries, the creation of wide-reaching international health organizations is a post-war invention. Organizations like the International Office of Public Hygiene and the League of Nations Health Organizations preceded the World Health Organization, but the WHO was intended to be the first truly universal health organization that would play a significant role in combating disease and improving lives on the ground around the globe.

That the organization was the brainchild of a particular postwar moment is perhaps best evidenced by a statement in the WHO’s constitutions that notes that “the health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security.” The founders of the organization believed that promoting well-being for all peoples of the world, “regardless of race, religion, or political belief” would be an essential component in preventing another conflict like the one the world had just suffered through.

How did the role of health organizations in West Africa change after independence (post-1960)?

The end of colonial rule from the late 1950s to the early 1970s gave international health organizations much more latitude to expand their roles. Efforts focused on eradicating malaria and smallpox, improving child nutrition, and developing health care infrastructure, like clinics and hospitals. At the same time, doctors from former colonial states often maintained informal partnerships with medical professionals in these new African states, sometimes working through the framework of international organizations to continue their work.

As you study the Ebola epidemic through the lens of a historian of public health, do you see analogies with other transnational diseases: bubonic plague, yellow fever, cholera? Are these analogies useful in gaining perspective on what we’re currently living through?

Excellent question! For me, what all of these diseases teach us is how connected the world has always been and how we must work together to find solutions to the biggest threats to human security. I see many analogies between what face today with Ebola and what politicians and medical professionals faced in earlier eras with plague, yellow fever, and cholera. What concern me most are the dangers of misunderstanding of the mechanics of transmission. When doctors and diplomats from 12 countries met in 1851 to discuss the possibilities of quarantines to prevent the spread of plague and cholera, most could not agree on how these diseases were transmitted. Their solution was to un-invite the doctors from the next meeting (1859), arguing that this was primarily a political, and not a scientific issue. We’ve seen the danger of medical misunderstanding and misinformation in the Ebola epidemic. It’s imperative to work collaboratively to reconcile local cultural, social, and political constraints with scientific realities of disease transmission.

You remarked to your students that diseases have always been transnational. They have no respect for man-made geographic borders. Yet, when we talk about disease, particularly Ebola, we speak of it as an “African” disease. We use the borders we’ve drawn as means to isolate issues that are global in nature–a sort of “other-ing” use of geography. What’s really going on when we speak and think about global issues in such local terms?

Geography has been used to create an African “other” in the context of the current Ebola epidemic. Elements of the American media have been quick to construe Ebola as an “African problem,” while in reality Africa is a vast and vastly diverse continent, and the epidemic has been limited to a small part of West Africa. Some of the coverage of the epidemic relies on colonial tropes of African backwardness, and depicts Africa as an uncivilized and diseased continent. What we need is to both familiarize ourselves with the actual geography of the epidemic as well as the reality of African diversity, and to move away from language that paints Africa as a backward place in need of Western civilization. Africans are actively involved in fighting the epidemic and it is only though a model of partnership that we can hope to eliminate the disease.

Jessica Pearson-Patel is an assistant professor in the Department of International and Area Studies at the University of Oklahoma. She is currently working on a book manuscript provisionally entitled “The Colonial Politics of Global Health: France and the United Nations in Postwar Africa.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com