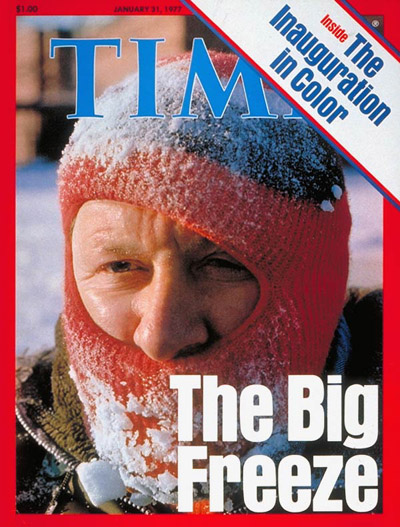

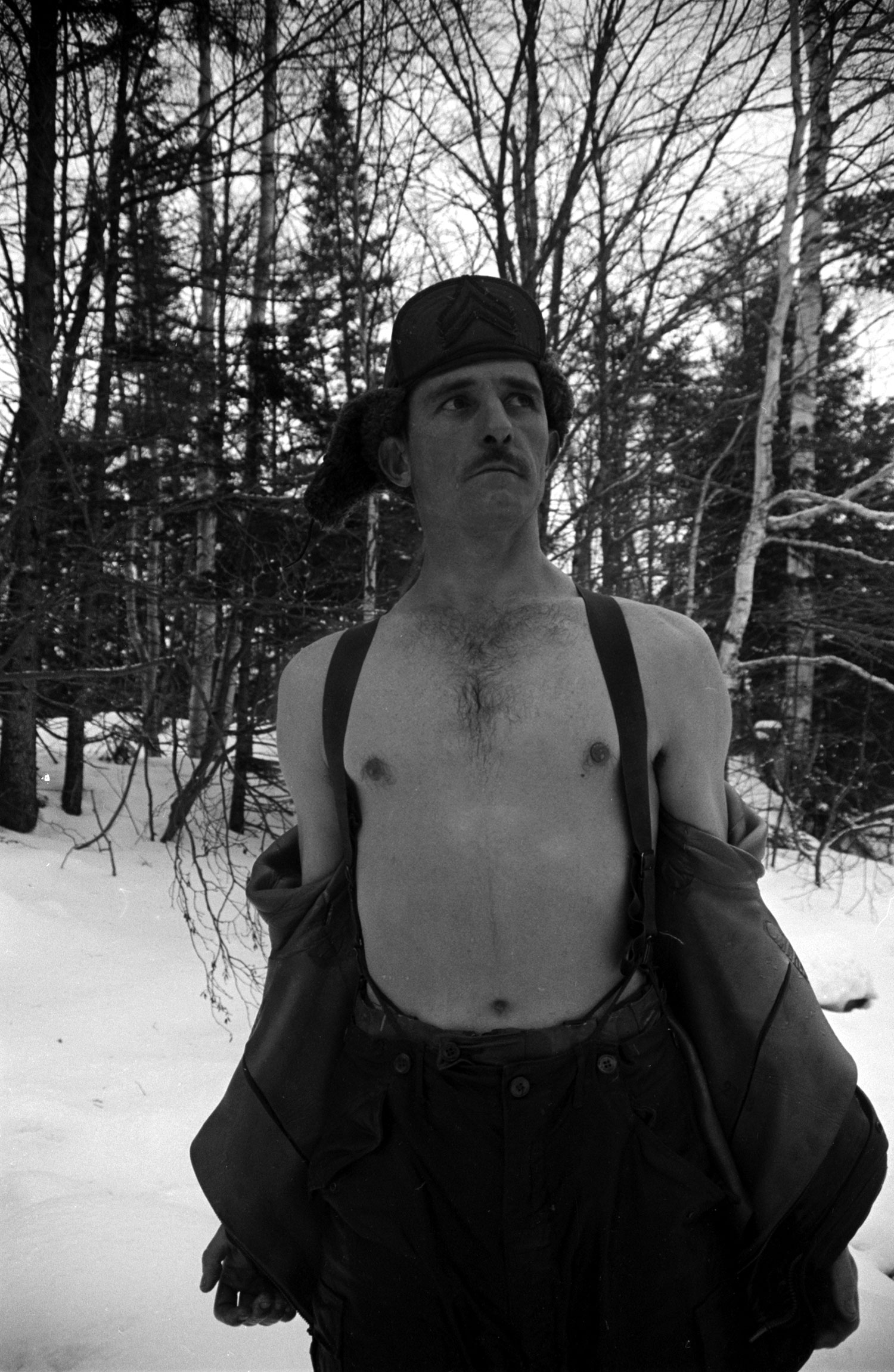

It was Jan. 31, 1977, when this poor freezing man appeared on the cover of TIME. The story inside, which detailed the effects on the United States of what the publisher’s letter called “the bitterest cold spell in memory.”

The first-ever reported snow fall in West Palm Beat, Fla., had shocked residents. Buffalo had been buried under more than 120 in. of the white stuff that season. And, ironically, areas that needed snow — the ski resorts of Idaho, for example — had to rely on snow-making machines despite the cold temperatures. Record lows were reported in cities nationwide. The natural-gas industry went into crisis mode. Maryland declared a state of emergency as the state’s seafood industry was shut down by a frozen bay.

But, of course, 1977 wasn’t the only year that the U.S. suffered under snow — and, right now, the Northeast is bracing for what promises to be a major blizzard.

Here are the stories of seven other noteworthy storms from American history, as told by TIME:

From the Nov. 25, 1946, issue: Blizzard on the Prairie

When a major storm hit Colorado, ranchers found that feeding and protecting their herds was more difficult than ever:

The sun disappeared behind a grey overcast, and a great stillness fell over the eastern Colorado plains. After that a freezing wind rose, banged barn doors and snatched at the smoke from lonely ranch houses. It grew dark, and salt-like snow began hissing across leagues of sere buffalo grass. Then, for 48 hours, a blizzard—the worst in 33 years—moaned down out of Wyoming with nothing to stop it but fence posts and cottonwood trees.

As the prairies whitened, scores of thousands of chunky Hereford cattle turned tail to the storm, lowered their heads, and began to drift disconsolately before it. When they came to fences they turned, followed the wire. But some time during the second night, when the snow was belly deep on the flats and higher than a rider’s head in the drifts, they stopped. When the storm ceased and the cold intensified, herd after herd stood wearily with their breaths steaming, waiting patiently for death.

Read the rest of the story here

From the Jan. 5, 1948, issue: The Big Snow

Though New Yorkers “disregard nature until it makes more noise than the subway,” a storm at the turn of 1948 got their attention:

Suddenly the city began to realize what was happening. It was seeing its heaviest snowfall in Weather Bureau history (76 years). At midnight, 18 hours and 35 minutes after the storm began, the Weather Bureau announced that 25.8 inches had fallen. It was 4.9 inches above the record set in the legendary three-day blizzard of 1888.

By 5 o’clock, central Manhattan subway stations were jammed with pushing, gesticulating throngs. Shoe stores were invaded by snow-powdered hikers in search of rubbers and galoshes. Hotels were besieged; and a backwash of the stranded headed for bars, all-night movies and the apartments of friends. Meanwhile the Fire Department was struck by the horrible thought—it couldn’t move its trucks. Its engine-house gongs rang out the “five sixes” (all firemen report for duty). It got radio stations to ask the citizenry kindly not to let their houses burn down.

Read the rest of the story here

From the Feb. 17, 1961, issue: The Cause of the Snow

Blizzards in 1961 were, TIME reported, due to a vicious cycle of weather, in which storms kept the ground from warming, which allowed cold air to get up under warmer winds, causing further storms. The result was a string of bad weather nationwide:

Particularly in the East, the frozen, snow-strangled U.S. last week could only echo General George S. Patton’s exasperated wartime injunction to his chaplain: “Goddam it, get me some good weather!”

Not since Dec. 1 had the cities and farms east of the Mississippi seen even reasonable winter weather. Ferryboats froze in Lake Michigan. Georgia peach trees shivered in the coldest winter in 25 years. New York City, buried under 55.7 inches of snow that had fallen this season, also endured 16 days of continuously below-freezing temperatures. Last week, in a taxi driver’s dream of heaven, private cars were banned in Manhattan for five days to facilitate snow removal, which so far has cost the metropolis some $20 million.

Read the rest of the story here

From the Feb. 3, 1967, issue: The 24-Million-Ton Snow Job

When Chicago was hit with a record 23 inches of show in 1967, it shut down the city almost entirely:

Chicagoans knew that the balmy 65° weather could hardly last—it was, after all, the warmest Jan. 24 on record— but they little dreamed how startling the change would be. Within two days, the temperature plummeted to the 20s, snow came cascading down, and icy winds gusted through the streets. Though no stranger to wintry storms, Chicago found itself in the brief space of 24 hours paralyzed by the worst blizzard in its history—a raging storm that tore through large sections of the Midwest and caused at least 75 deaths.

The howling blast began Thursday morning. By midafternoon, Chicago’s streets were clogged by wind-whipped snowdrifts and stalled autos. With traffic at a standstill and visibility at zero, tens of thousands of marooned workers had to spend the night in firehouses, hospitals and hotels. On the Calumet Expressway, 1,000 stranded motorists joined hands so that they would not get lost, snaked their way to nearby homes. A 50-year-old woman suffered a fatal heart attack on a stalled bus at 5 a.m. Friday. Not until six hours later could snowbound police remove her body.

Read the rest of the story here

From the Feb. 6, 1978, issue: Now It’s The Midwest’s Turn

A blizzard in early 1978 struck the East first, before turning bringing the Midwest to a stand-still and costing the auto industry an estimated $130 million:

Enough already. First the winter of ‘78 clobbered the East with heavy snow (Boston, 21 in.; New York, 16 in.), the West with drenching rains and high winds, the South with frigid temperatures and a score of tornadoes. In Massachusetts, the state’s $9 million snow-removal budget is already exhausted. California drought officials traded in their sun visors for umbrellas and began dispensing flood-control information. Motorists in Georgia shuddered at the foreign squeal of back tires spinning on ice.

Last week it was the Midwest’s turn. Roaring through the upper Midwest, the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley, from the Appalachians to the Canadian border, a blizzard blasted 31 in. of snow across Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin. With winds clocked at up to 100 m.p.h. (hurricane force is 75 m.p.h.), the wind-chill factor hitting–50o and record-low barometric readings, the National Weather Service classified the big blow as an “extratropical cyclone.” That scarcely did justice to this great white whale of a storm. An NWS spokesman in Detroit called the blizzard “one of the worst, if not the worst,” In Michigan’s history. Kentucky Governor Julian Carroll said it was “the most devastating snow accumulation in 100 years.” Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes also deemed the storm the worst ever in his state–”a killer blizzard looking for victims.”

Read the rest of the story here

From the Feb. 20, 1978, issue: Blizzard of the Century

The bad weather of 1978 continued as Providence received 26 inches of snow, coastal landmarks in Massachusetts were destroyed and temperatures even in the South plunged down to well below freezing:

Buffeted by winds of up to 110 m.p.h., a 42-ft. Coast Guard pilot boat, the Can Do, capsized and sank in Salem Harbor. The captain and the four-man crew were drowned. In nearby Nahant, Melvin Demit, 61, was lighting the furnace in his basement, when a wall of water crashed into his house and engulfed him. In Scituate, a raging sea swept five-year-old Amy Lanzikos to her death just as a rescue boat was bringing her to safety.

This was the scene along the Massachusetts coast last week, as a mammoth blizzard–the worst since 1888–slammed the Northeast, dropping from 1 to 4 ft. of snow in the latest blast from a winter of stormy discontent. Raging from Virginia to Maine, the hurricane-like storm killed at least 56 people, caused an estimated half billion dollars’ worth of damage and crippled Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island for five days.

Read the rest of the story here

From the Jan. 22, 1996, issue: The Blizzard of ’96

A more recent blizzard drew complaints from some New Yorkers that there were “no trains, no cabs, no nothin’ — just snow”:

It was eraser on a near impossible scale. First the sky went blank, and then the ground. Then, in most places, your front steps disappeared, then your car; and finally, your schedule for the next 48 hours. How big was the snowstorm that hit the Eastern states early last week? So big that in each new place it bulldozed over, it toppled a different historical precedent. In New York City they compared it to the great storm of 1947. In Boston it was the blizzard of 1978. In Raleigh, North Carolina, the snow of 1989. That won’t happen next time. Whenever they do their recollecting, January 1996 will be the Last Big Storm for the entire East Coast.

It was a classic nor’easter that happened to stretch over 20 states and do tremendous damage. At least 100 lives were lost, many to heart attacks triggered by Sisyphean shoveling. Bill Clinton called the storm a “national disaster” and promised federal relief. In the New York region alone, an estimated $1 billion was lost to interrupted business and cleanup costs.Every region got more than it was prepared for. An inch of icy snow sufficed in Atlanta, where tractor-trailers skidded across highway lanes and the indoor Peachtree Center shopping area became deserted.

Twenty-four inches knocked out Washington; Philadelphia got a record 30.7, and New York City endured 20.6. Even jaded Boston, with 18.2 inches, postponed a Bruins hockey game (against the Colorado Avalanche).

Read the rest of the story here

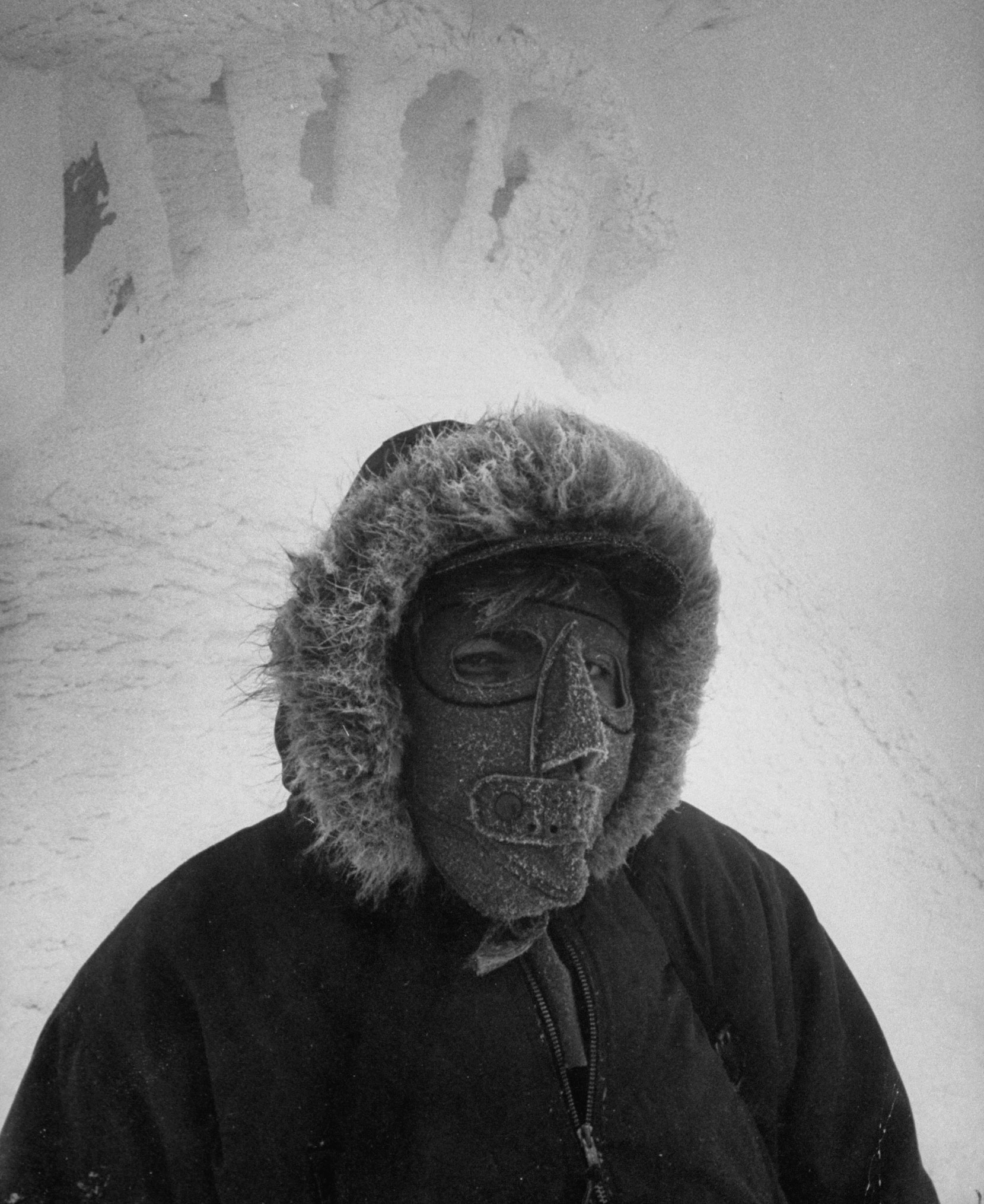

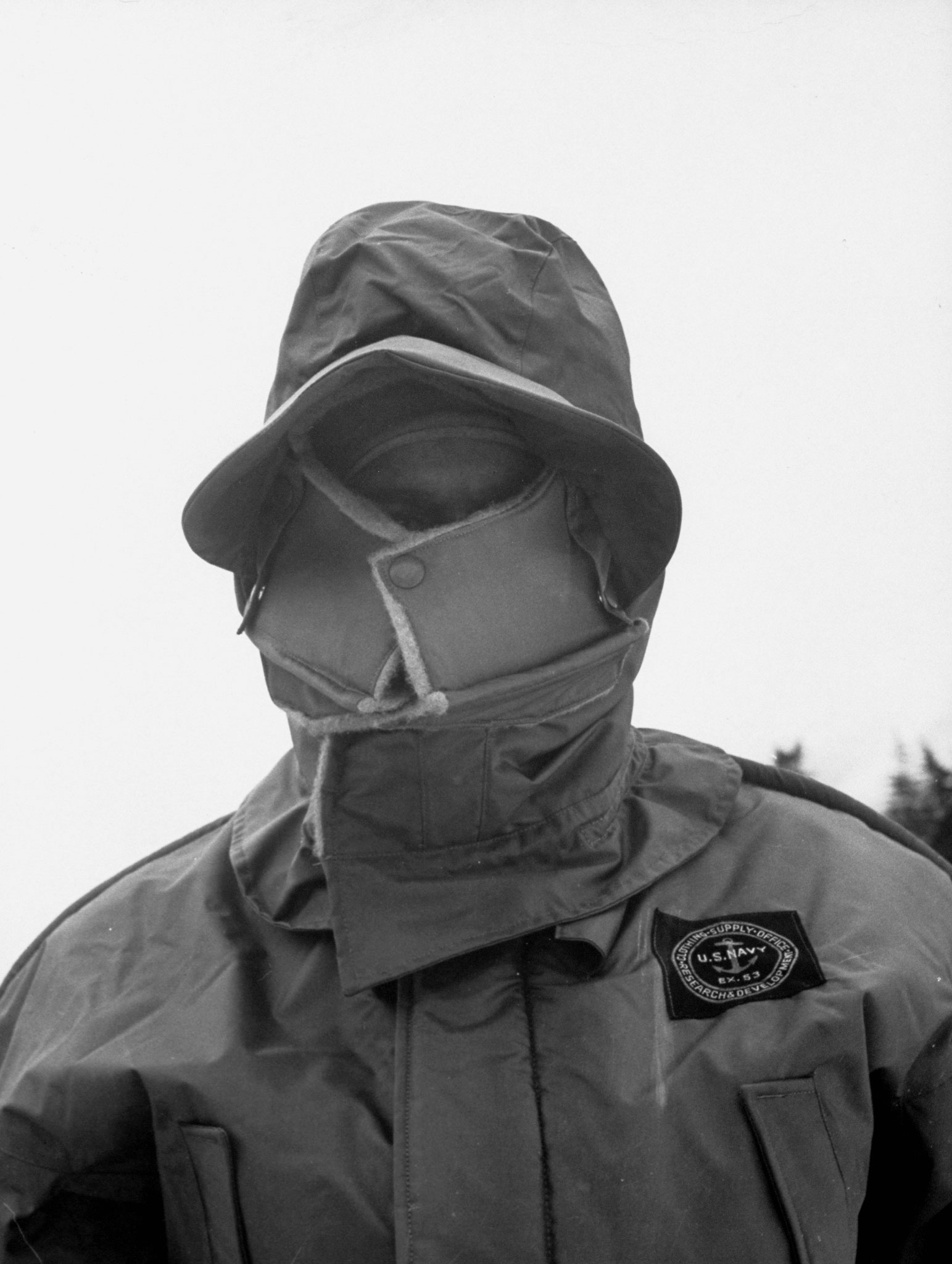

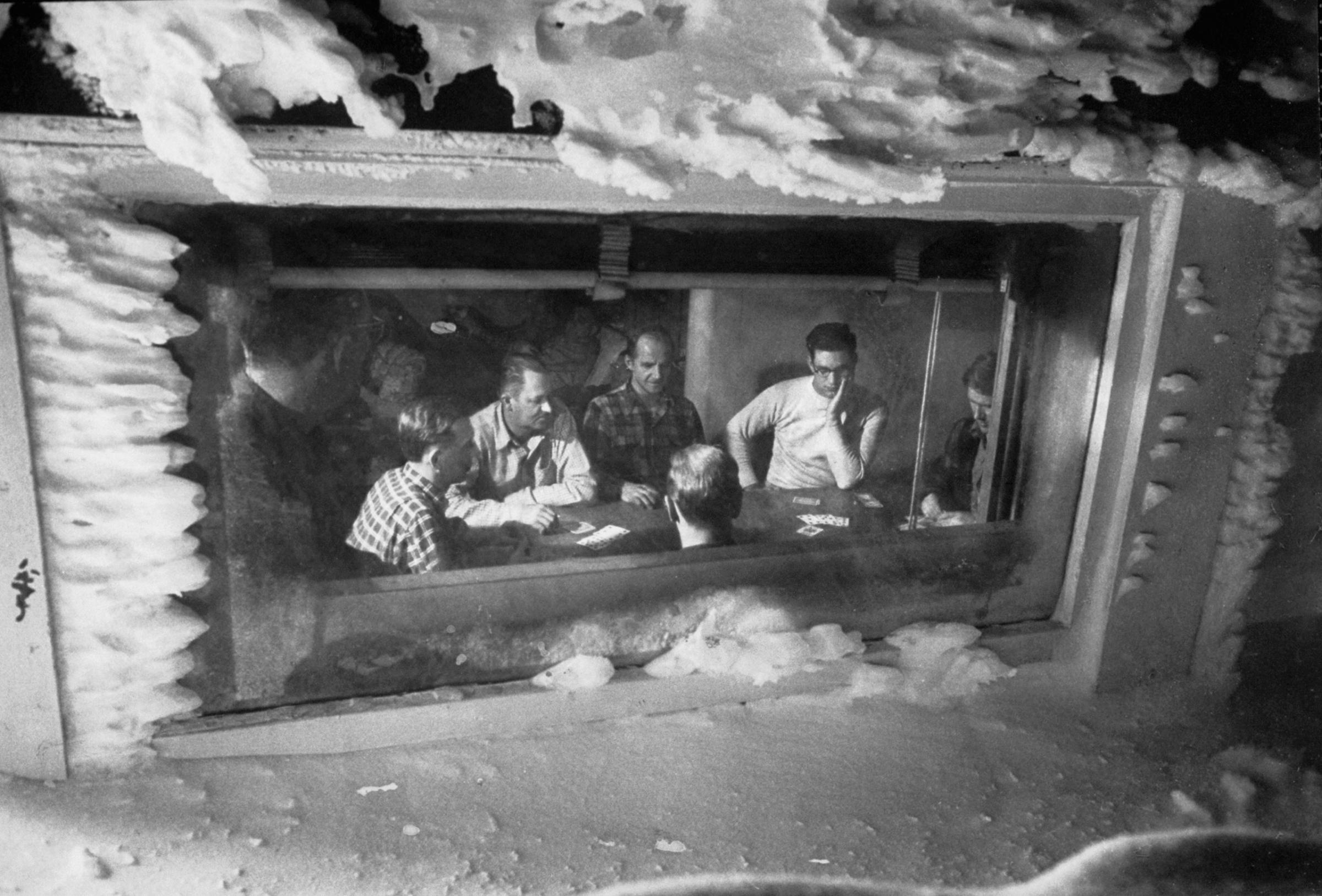

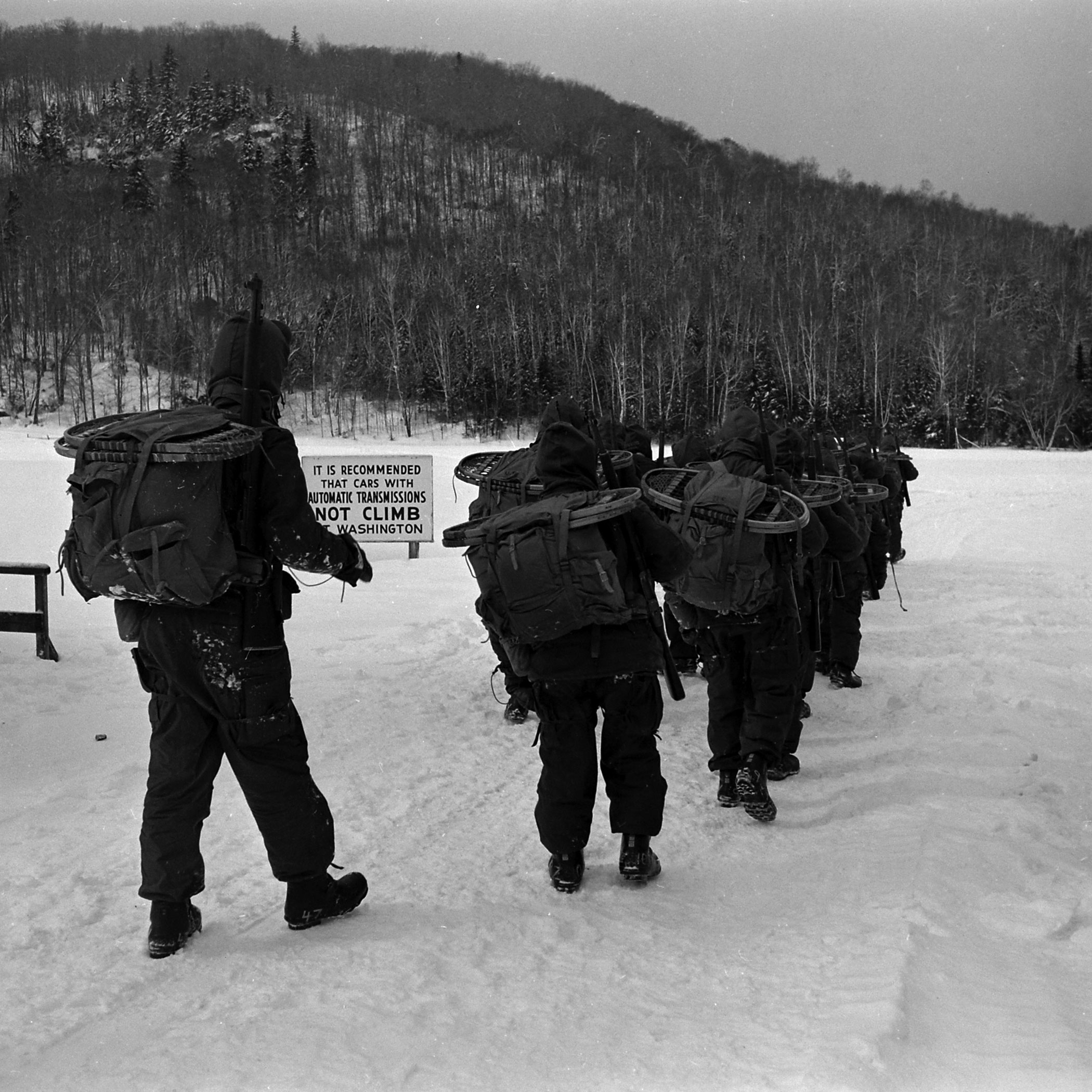

Where the World's Worst Weather Is Born: Photos From Mount Washington

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com