In 1939, this seemed the most topical of novels: the story of one Oklahoma family, the Joads, leaving their devastated Dust Bowl home to find work picking fruit in California and finding more misery and pricked hopes when they get there. But John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath also speaks urgently to today’s concerns: the cratered trail of dreams for Mexican immigrants seeking a promised land in the Western U.S.; the perfidy of banks in foreclosing on poor people’s homes; and the insurgent urge of the book’s protagonist, Tom Joad, to speak truth to police power. “Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy,” Tom promises, “I’ll be there.” In Salinas, Cal., Ferguson, Mo. or Staten Island, N.Y., Tom’s truth goes marching on.

TIME, in its April 1939 review, called the book “Steinbeck’s best novel, i.e., his toughest and tenderest, his roughest written and most mellifluous, his most realistic and, in its ending, his most melodramatic, his angriest and most idyllic.” That anger resonated through the decades and throughout popular culture—from, say, the 1941 Woody Guthrie ballad “Tom Joad” to Bruce Springsteen’s 1995 “The Ghost of Tom Joad.”

The echoes haven’t faded. In 2010, choosing The Grapes of Wrath as one of the all-TIME 100 Novels (published since 1923), Lev Grossman wrote of the Joads: “their indomitable strength in the face of an entire continent’s worth of adversity makes Steinbeck’s epic far more than a history of unfortunate events: It’s both a record of its time and a permanent monument to human perseverance.”

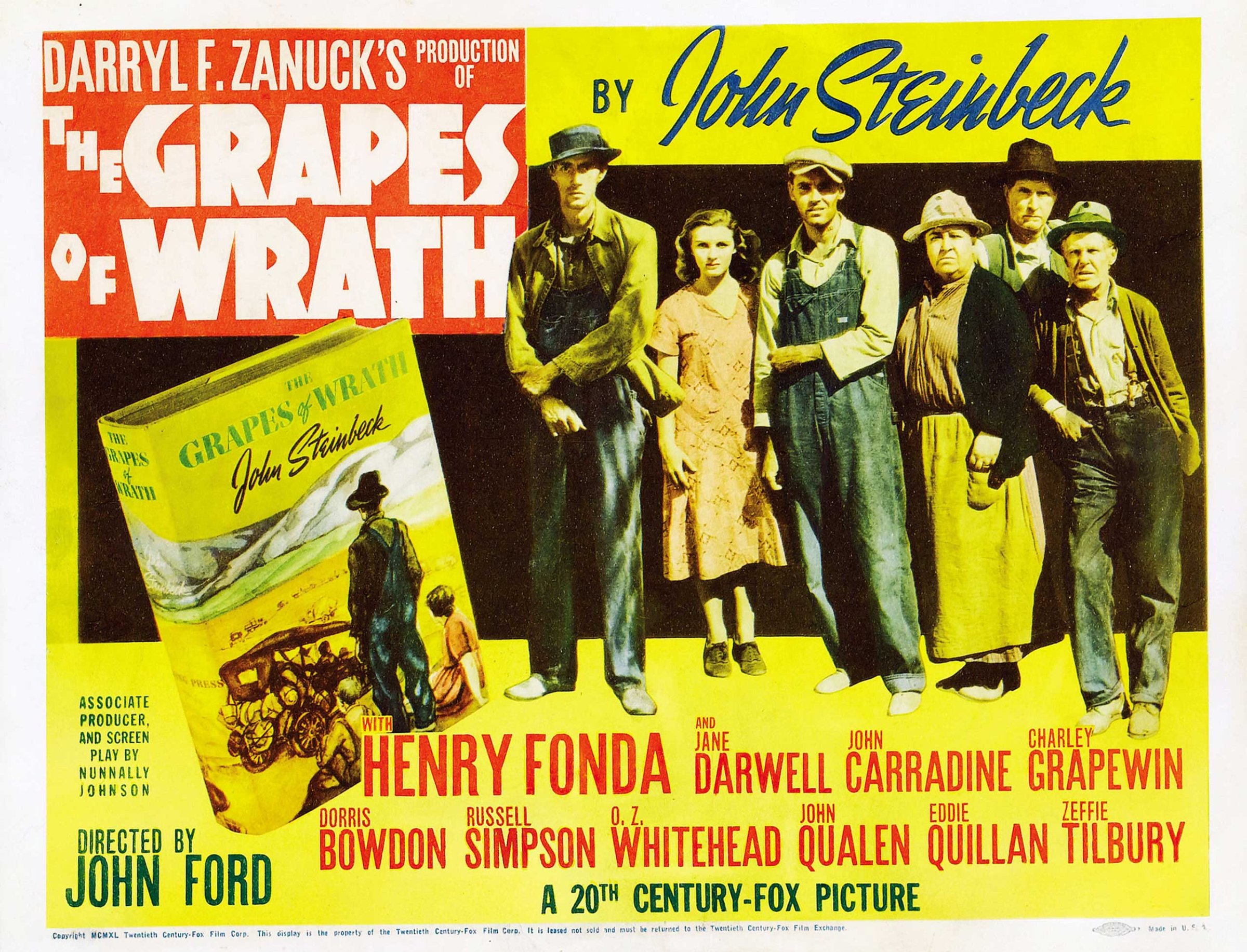

The same can be said of the film version of The Grapes of Wrath. Starring Henry Fonda as Tom Joad and directed by John Ford, it had its world premiere in New York City on Jan. 24, 1940—75 years ago today.

The movie, which would be named the year’s Best Film by the New York Film Critics Circle, was greeted with hosannahs from pertinent reviewers. One was Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times, who wrote that the movie deserved a place on that “small, uncrowded shelf devoted to the cinema’s masterworks, to those films which by dignity of theme and excellence of treatment seem to be of enduring artistry, seem destined to be recalled not merely at the end of their particular year but whenever great motion pictures are mentioned.” Years later, Nugent would write screenplays for 11 Ford films, including their joint masterpiece, The Searchers. But his Times review was no preemptive apple polishing for a future employer, simply the expression of the majority opinion.

The man who reviewed The Grapes of Wrath for TIME had a more complex career biography. Before coming to the magazine in 1939, Whitaker Chambers had already translated Felix Salten’s Bambi into English, written journalism and poetry for the Communist paper The Daily Worker and fiction for The New Masses and served as a spy for the U.S.S.R. against the U.S. government. Riven by news of the 1938 Moscow Trials, Chambers defected from the Party and was hired by TIME. Toward the end of his tenure as Senior Editor, he was the star witness testifying against Alger Hiss in the most prominent espionage trial of the postwar years. TIME has harbored some famous movie critics—James Agee, Manny Farber, Richard Schickel—but none so notorious.

Chambers poured a vat of his conflicted political passions into his rave review of the Grapes of Wrath movie, which he saw as an improvement on the Agitprop aspects of the book:

It will be a red rag to bull-mad Californians who may or may not boycott it. Others, who were merely annoyed at the exaggerations, propaganda and phony pathos of John Steinbeck’s best selling novel, may just stay away. Pinkos, who did not bat an eye when the Soviet Government exterminated 3,000,000 peasants by famine, will go for a good cry over the hardships of the Okies. But people who go to pictures for the sake of seeing pictures will see a great one. For The Grapes of Wrath is possibly the best picture ever made from a so-so book. It is certainly the best picture Darryl F. Zanuck has produced or Nunnally Johnson scripted. It would be the best John Ford had directed if he had not already made The Informer.

Read TIME’s Feb. 1940 review of The Grapes of Wrath, free of charge, here in the archives: The New Pictures

The 1930s birthed two great agrarian novels: Gone With the Wind from the viewpoint of the ruling class, The Grapes of Wrath for the underclass. And both were turned into movies that dared to be true to the books’ controversial themes. Just six weeks after David O. Selznick’s epic adaptation of the Margaret Mitchell novel premiered in Atlanta on its way to becoming the most popular film of all time, 20th Century-Fox hosted the New York City opening of The Grapes of Wrath. The property had gone from first printing of the book to finished film adaptation in about nine months. Everything happened faster back then.

Gone With the Wind, the decade’s best-selling novel, had been a natural for the movies, though its rosy view of slavery seems a harsh delusion today. Hollywood had long romanticized the antebellum South as a home of vanished gentility; D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, depicting the Ku Klux Klan as Arthurian knights freeing Southern gentlewomen from their black oppressors, was the first blockbuster feature film exactly 100 years ago.

In 1939, though, Steinbeck’s migrants’ tale was much more immediate: a scorched-earth headline, a suppurating wound. The book had been banned in Kern County, Cal., the end point of the Joad family’s travels, and burned in Salinas, Steinbeck’s home town. Some California theater owners didn’t care much for the real Okies either: they made anyone who looked like a migrant worker sit in the balcony’s “colored section.”

So why should Fox boss Zanuck go where no Hollywood film had gone before: to expose the inequities of capitalism as the Great Depression staggered into its second decade? Because Steinbeck’s book was an enormous popular and critical success; and because Zanuck was hungry for a prestige hit.

A staunch Republican from Yahoo, Nebraska, and the only gentile then in charge of a major movie studio, Zanuck had produced socially incendiary films (I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, Wild Boys of the Road) in his early-’30s job as head of production at Warner Bros. At Fox he got rich on Shirley Temple movies and nostalgic musicals starring Alice Faye but had never got near Oscar hardware. Now Zanuck would assign Ford (already an Academy Award winner for The Informer) and producer-screenwriter Johnson to make the film of 1940.

At first, Zanuck and Steinbeck circled each other warily. Determined to red-check the book’s charges of official brutality, the mogul sent private detectives to the migrant camps and found that conditions were even worse than Steinbeck had portrayed. The author, for his part, was troubled that Fox was owned by the Chase National Bank, whose president, Winthrop Aldrich, was the brother-in-law of John D. Rockefeller Jr. In one of those improbable twists that are supposed to happen only in the movies, Aldrich’s wife Harriet told her husband she loved the book—and that was enough for the banker. Zanuck got the green light and sealed a $100,000 deal with Steinbeck. Ford shot the movie, which cost $750,000 to produce, in an efficient 43 days.

Johnson, who had written The Prisoner of Shark Island for Ford and the 1939 Western hit Jesse James, quickly fashioned a script that distilled the 473-page book and wove some of Steinbeck’s descriptive chapters into the narrative. (Virtually all the film’s dialogue is from the novel.) Fonda, who had already starred for Ford that year in Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk, was Ford’s choice for Tom Joad; Fonda wanted it too. But Zanuck insisted that the actor sign a seven-year contract with the studio before giving him the part.

In return, Fonda gave a perfect performance, revealing the idealism that grows inside desperation. Tom, who has killed a man before the story begins and kills another at the end, is a dead man walking. As illuminated by cinematographer Gregg Toland’s low-key lighting, Fonda’s face is that of a spirit haunted by crimes and warmed by possibilities. He is both Guthrie’s Tom Joad and Springsteen’s Ghost of Tom Joad.

In a family saga with zero romantic interest, the towering female figure is Ma Joad, a dominant life spirit incarnate. Ford considered Beulah Bondi for the role, then gave it to the more maternally configured Jane Darwell. The young Orson Welles, in Hollywood in 1940 to make Citizen Kane, said that by emphasizing Ma’s role Ford had turned The Grapes of Wrath into “a story of mother love. Sentiment is Jack’s vice.” But the movie needs Ma’s flinty optimism. If Tom is the firebrand of the family, Ma is the hearth. And Darwell brings a truculent warmth to the film. Somebody has called her one of the all-time great movie mothers.

Ford filled out his cast with a character actors’ Hall of Fame: sepulchral John Carradine as the itinerant preacher Casy; John Qualen as poor Muley, the Oklahoma landowner who must watch a tractor turn his shack into tinder; and Ward Bond, the director’s favorite supporting star, as a California cop. Dorris Bowden, Nunnally Johnson’s wife, was the pathetic Rosasharn, who in the novel’s conclusion is so overwhelmed with grief at losing her infant baby that she feeds her mother’s milk to a dying stranger. That scene didn’t get into the movie (no surprise, since Steinbeck’s editors had wanted it out of the book) nor did several scenes of political fingerprinting.

In fact, the film’s famous ending was not shot by Ford.

Anyone who’s seen the movie remembers the two final speeches. The first is Tom’s, when he leaves his mother to become the floating conscience of working-class America’s threats and promises: “I’ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be everywhere, wherever you can look. Wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready. And when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build—I’ll be there, too.”

Tom and Ma kiss—the movie’s one fervent expression of emotion—and we see an image of Tom walking away on a hill crest toward an uncertain future. That, Ford thought, should be the final shot. “I wanted to end on a down note,” he said later. “And the way Zanuck changed it, it came out on an upbeat.” A meticulous and dominant craftsman on the set, Ford usually left his films to be cut by Zanuck, whom he greatly admired as an editor; and this time, Zanuck wanted to show that, for the Joads, to survive was to triumph. So he pulled a speech from earlier in the book (and from an earlier draft of the screenplay) to express an affirmation of almost Constitutional grandeur. Instead of “We the People,” “We’re the people.”

The family finds a government camp that treats migrants decently and informs them of 20 days’ work nearby. And in their rickety car, Ma tells Pa Joad (Russell Simpson) about the indomitability of the poor: “Rich fellas come up an’ they die, an’ their kids ain’t no good an’ they die out. But we keep a-comin’. We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out, they can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever, Pa, ’cause we’re the people.” The scene is filmed in a single two-shot of about 1min.45sec. And Zanuck directed it himself.

Steinbeck, who saw the movie about a month before it opened, might have balked at some ellipses and euphemisms. But he loved it. “Zanuck has more than kept his word,” he wrote in a letter read by Ford historian Joseph McBride in an illuminating commentary on the film that appeared in the 2007 box set Ford at Fox. “He has [produced] a hard, straight picture to which the actors are submerged so completely that it looks and feels like a documentary film. And certainly it has a hard, truthful ring. No punches are pulled. In fact, with the descriptive matter removed, it is a harsher thing than the book by far. It seems unbelievable but it is true.”

Nearly as incredible is that, the following year, the film lost the Oscar for Best Picture to Selznick’s romantic mystery Rebecca. Only Ford and Darwell received Academy Awards. In 1941 Ford left Hollywood for four years to shoot war documentaries in the Pacific (his The Battle of Midway is a classic), eventually rising to the rank of Admiral. Fonda also joined the Navy, earning Lieut, JG stripes and a Bronze Star; and Zanuck was commissioned as a Colonel in the Army Signal Corps. Steinbeck, whom the FBI had investigated for Communist leanings around the time of The Grapes of Wrath, was not allowed to join the Armed Forces. He became a war correspondent for the New York Herald-Tribune and was informally involved in the OSS, predecessor of the CIA.

If The Grapes of Wrath speaks with eerie eloquence to Americans today, it had an immediate effect on two prominent viewers across the Atlantic. Seeing the movie several times in 1940, Adolf Hitler was convinced by its dramatizing of downtrodden Anglo-Saxon farmers that U.S. soldiers from such a debased stock would be a pushover in any war against the Third Reich. Turned out Hitler was misinformed, or a dupe of American propaganda. He must have turned the movie off before the “We the people” speech.

And in 1948 Joseph Stalin allowed the film to be shown in theaters in the U.S.S.R., believing that audiences would be enlightened by the misery of the proletariat in the so-called Golden State, the self-described America the Beautiful. Stalin was wrong too. Soviet moviegoers gazed enviously on the jalopy that took the Joads from Oklahoma to California. The message Russians took from The Grapes of Wrath: even the poorest capitalists have cars!

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com